—Alexis de Tocqueville, Journey to America1

Life

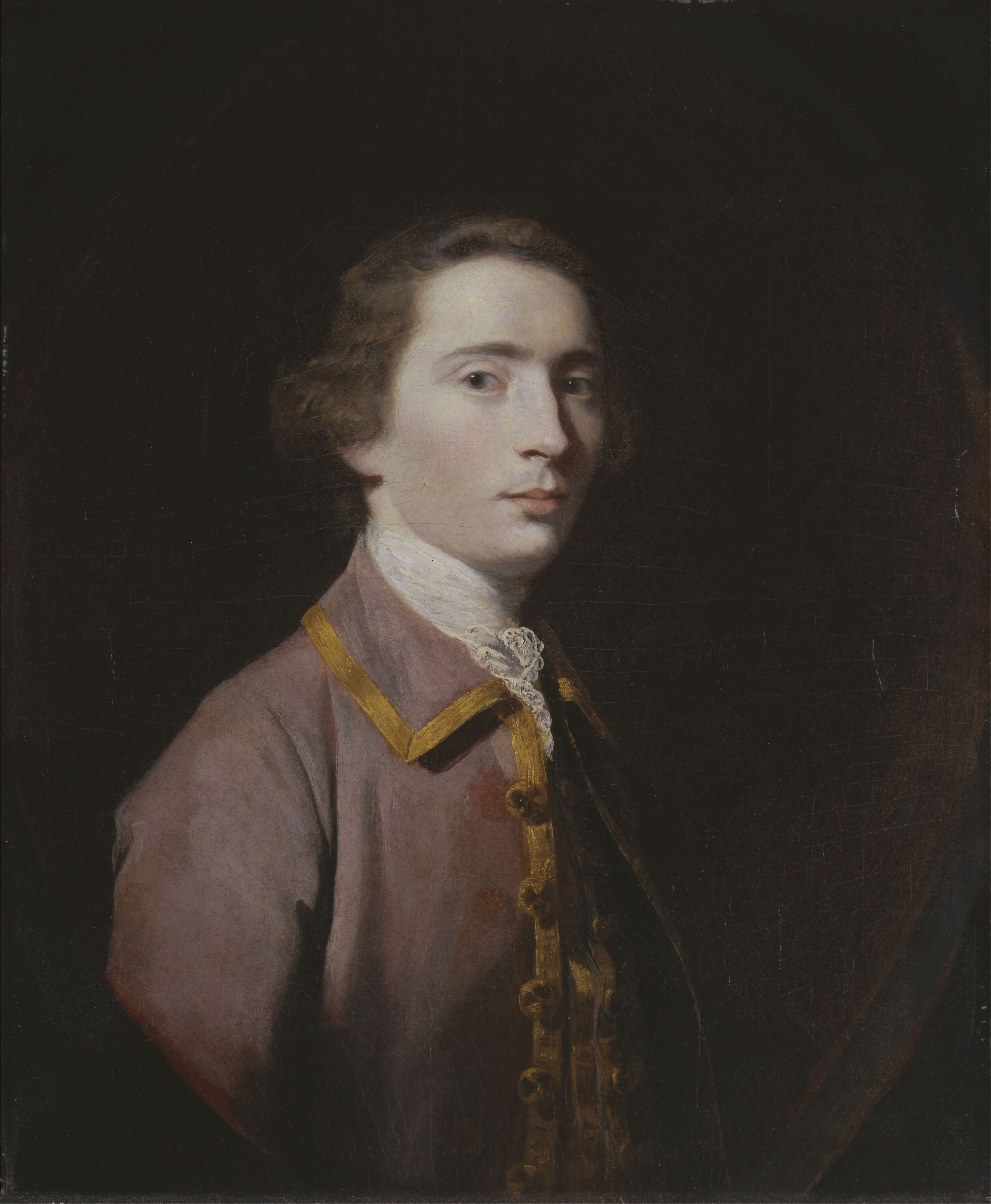

Charles Carroll of Carrollton was born on September 19, 1737, in Annapolis, Maryland, to a prominent Irish Catholic family. In 1748, at the age of 11, Carroll travelled to France to study at the Jesuit College of St. Omer, and continued his studies in Paris and England. Carroll returned to Maryland in 1765. Shortly after the death of his fiancée, Rachel Cooke, Carroll married his cousin Mary (Molly) Darnall on June 5, 1768. They had seven children, three of whom survived past infancy. Carroll made his political debut as the “First Citizen” in the early 1770s and later became a Maryland State Senator and U.S. Senator. He died on November 14, 1832, in Baltimore.

Education

Carroll received his BA at the College of St. Omer in northern France and MA in philosophy at the Louis-le-Grand in Paris. He studied civil law and common law in France and Great Britain.

Religion

Roman Catholic

Political Affiliation

Federalist (moderate)

Highlights and Accomplishments

1773: Author, “First Citizen” letters

1776: Signer, Declaration of Independence (only Catholic to sign)

1776: Member, committee that drafted Maryland Constitution

1776–1778: Delegate from Maryland to Continental Congress

1777–1800: Maryland State Senator

1789–1792: U.S. Senator

1832: Last of the Signers to die

Life of Charles Carroll

The last of the American signers of the Declaration of Independence to pass from this world, Charles Carroll of Carrollton was also one of the most formally educated of the American Founders. Living 17 years in France and England, Carroll earned his BA in the traditional liberal arts and an MA in philosophy. He also studied civil law in France and common law in England.

Irish immigrants to the English American colonies, the Carrolls suffered at the hands of anti-Catholic bigots in Maryland for three generations. When Charles Carroll came into the world, his parents remained unmarried because of the law and chose to send their only son to live in France. Had they educated him in Maryland, the authorities had the legal sanction to remove children—taught in a “Catholic fashion”—from the parents and place them permanently with English Protestants. Although America is called “the land of the free,” its 13 English colonies were anything but tolerant. More than any other colony in the 17th century, Maryland promoted religious toleration, but a coup in the name of William and Mary in 1689 ended that tolerance for nearly a century. Maryland went from being one of the world’s most tolerant societies (and arguably the most tolerant society) to one of the least tolerant almost overnight.

Beginning in 1689, Catholics were not allowed to participate in politics or the law, nor were they allowed to worship openly or freely. However, they remained generally free in their property rights. They could own land and lend (and borrow) money, but they were double-taxed, and their lands were always subject to forfeiture. The Carrolls used the freedom of property rights to accumulate huge sums of wealth, some sources suggesting they were among the wealthiest families in the colonies by the time of the American Revolution.

In the summer of 1748, Charles Carroll sailed across the Atlantic and became a student at St. Omer. The school was founded in 1593 on the Aa River in the Pas-de-Calais, and the mission engraved above its entrance revealed its intentions without trepidation: “Jesus, Jesus, convert England, may it be, may it be.” Known to English Catholics as “the seminary of martyrs—the school of confessors,” the college offered the Jesuit version of the liberal arts, the “Ratio atque Institutio Studiorum Societas Jesu” (“Method and System of the Studies of the Society of Jesus”) or, in its abbreviated form, the “Ratio Studiorum.”

Based on the Spiritual Exercises and the teachings of the founder of the Society of Jesus, St. Ignatius of Loyola, the Ratio Studiorum reflected the martial, humane, and rigorous spirit of the Jesuits. Additionally influenced by the teachings of Spanish humanist Luis Vives and Strasburg educational theorist John Sturm, the Ratio Studiorum combined scholastic and humanist methods, ideals, and goals. True to the Catholic teachings of such vital figures as St. Augustine, the Ratio Studiorum allowed for local options as long as the local schools remained true to larger, universal principles. Therefore, what Carroll learned at St. Omer reflected to a great extent the beliefs of the local Catholic community as well as those of the superior or rector of the school.

Over six years, a student, led by a (hopefully) devoted tutor, studied literature, philosophy, and science. The curriculum called for frequent recitations and intense repetitions—through compositions, discussions, debates, and contests—on the part of the student. The Ratio Studorium also promoted physical exercise, mild discipline in terms of punishments, and serious “moral training.” Students learned Greek and Latin throughout the six-year course, and the system encouraged the speaking of Latin even in casual conversation. Ultimately, the student was to aim for “the perfect mastery of Latin” and especially “the acquisition of a Ciceronian style.” With the six-year course, the Jesuits helped to release and harmonize “the various powers or faculties of the soul—of memory, imagination, intellect, and will.”2

By late November 1753, as Carroll graduated, he received the highest praise of all. His master, Father John Jenison, claimed he was “the finest young man, in every respect, that ever enter’d the House.” Hoping not to have his words considered an exaggeration, Father John explained:

’Tis very natural I should regret the loss of one who during the whole time he was under my care, never deserv’d, on any account, a single harsh word, and whose sweet temper rendered him equally agreeable both to equals and superiors, without ever making him degenerate into the mean character of a favorite which he always justly despis’d. His application to his Book and Devotions was constant and unchangeable…. This short character I owe to his deserts;—prejudice, I am convince’d, has no share in it.3

Father John assured Charles’s father that the community of priests and students shared this view of the graduating Carroll.

“First Citizen”

When Carroll returned to Maryland in 1765, he remained aloof from politics because of his non-legal standing as a practicing Roman Catholic. As the American colonies moved toward independence from Britain, however, Carroll accepted the role of republican and conservative revolutionary. In 1773, two debates dominated political discourse: whether the governor had the right to issue taxes and whether or not the Church of England should enjoy a legal monopoly in the colony. Revealing his liberal education as inculcated by the French Jesuits, Carroll challenged both ideas, writing under the pseudonym “First Citizen.”

Over four debates—carried on formally in the main Maryland newspaper and informally on the streets and in every pub in the colony—Carroll challenged the more pro-British ideas of Daniel Dulany (“Antilon”).

During the debates, Carroll drew upon a number of classical (Cicero and Tacitus especially) and medieval figures as well as recent thinkers. For example, he began his fourth letter with arguments of Lord Bolingbroke, a “noble author,” and peppered it with quotes from legal theorists, satirists, fellow Founders, and philosophers; historians Sir Edward Coke, William Hawkins, and Sir William Blackstone; Dulany, who had published an attack on the Stamp Act; and David Hume, Jonathan Swift, John Dickinson, Alexander Pope, and John Milton, concluding with the words of Horace. This gives us an indication of his education and the influences upon him as he studied at St. Omer.

His arguments are even more interesting. While continuing his claim that fees were taxes, he posited much of the debate in terms of man’s will, sophistry, and ingenuity against eternal truths and natural law. Though distrustful at times of the “earthiness” of the common law as opposed to the “other worldliness” of the natural law, Carroll explained the role of inherited rights succinctly. “[I]t required the wisdom of ages, and accumulated efforts of patriotism, to bring the constitution to its present point of perfection; a thorough reformation could not be effected at once….” And yet Carroll, like many of his contemporaries, found the notion of inherited rights and the common law to be somewhat haphazard and lacking. “Upon the whole,” the “fabrick is stately, and magnificent.” However, he continued, “a perfect symmetry, and correspondence of parts is wanting; in some places, the pile appears to be deficient in strength, in others the rude and unpolished taste of our Gothic ancestors is discoverable.”4

But Carroll also believed that these flaws should never call into question the necessity or importance of inherited rights or the common law. The long, gradual process of discovery through trial and error reveals the flawed state of man, his creations, and his political orders. “Inconsistencies in all governments are to be met with,” First Citizen recognized. Even in the English constitution, “the most perfect, which was ever established, some may be found.”5

True civilization, then, must recognize the limitations of man in his fallen or flawed state. It recognizes the expansive nature of pride in men. Therefore, Carroll argued, taking his claim from Blackstone, proper liberty comes best from “the limited power of the sovereign.” Only a vigilant, wise, and virtuous people can maintain a free society. “Not a single instance can be selected from our history of a law favourable to liberty obtained from government, but by the unanimous, steady, and spirited conduct of the people.”6

Carroll believed that the Anglo–Saxon culture and constitution best manifested this spirit of liberty but that the Norman Conquest of 1066 had destroyed it. “The liberties which the English under their Saxon kings, were wrested from them by the Norman conqueror; that invader intirely [sic] changed the ancient by introducing a new system of government, new laws, a new language and new manners.”7

“CX”

On May 27, 1774, 161 citizens of Maryland, including the Dulanys, signed a counter-resolution protesting the resolves and the legitimacy of the meeting of the Annapolis Convention of May 25.8 “All of America is in a flame!” wrote William Eddis, an officer serving in the administration of Maryland governor Sir Robert Eden. Nearly the entire population of Maryland, according to Eddis, has “caught the general contagion. Expresses are flying from province to province. It is the universal opinion here that the mother country cannot support a contention with these settlements.” Eddis foresaw nothing but disaster for the colonies. Nevertheless, he held out hope because, in his view, the Annapolis Resolves were written by disreputable figures. The truly important men of the community, those of “first importance in this city and in the neighborhood,” had signed the counter-resolution.9 All those of “first importance” had to do now was make the population realize this.

However, as Eddis fully understood and regretted, the sentiment of the Marylanders ran against these counter-protestors. Extralegal meetings in Queenstown on May 30, Baltimore on May 31, and Chestertown on June 2 passed resolutions supporting the Annapolis Resolves of May 25, thanking the citizens of Annapolis for their patriotism and initiative, and calling for a general Convention to meet to decide the fate of Maryland and her support of Boston. On June 4, 1774, the extralegal Annapolis meeting reconvened and elected representatives to this first general Maryland extralegal Convention. The first Convention, made up of 92 men, met in Annapolis from June 22 to June 25, 1774, discussing primarily the fate of Boston and the British denial of the Massachusetts charter. The Convention condemned the acts of Parliament as “cruel and oppressive invasions of the natural rights of the people of the Massachusetts bay as men, and of their constitutional rights as English subjects.”10 The Convention more or less embraced the Annapolis Resolves of May 25 and elected five men, including William Paca and Samuel Chase, “or any two of them,” to be representatives to a Congress of all colonies if one should be called.11 Similar calls for a colonial-wide assembly were made throughout the 13 colonies.12

Carroll placed his own understanding of the events of 1774 in the classical and Whiggish historical and mythical Anglo–Saxon frameworks. Additionally, having known Edmund Burke personally, Carroll’s own views significantly reflected those of the Anglo–Irish statesman. In several very open and emotional letters to William Graves, he discussed those views. “Provincial committees constituted of deputies nominated by their respective counties have met in the capital city of each [colony] to collect the sense of the whole colony,” he wrote in August 1774. Together, these delegates would meet on September 5 in Philadelphia. Most likely, he predicted, this Congress would challenge “the corrupt ministers intent on spreading that corruption thro’ America” by ending all imports of British goods into America.13 Further, he claimed with exuberance, any person blocking these resolves in any way would be treated as the Romans treated criminals against the state: by executing them.

Six months later, Carroll gladly informed Graves that the committees fully controlled America: “Our numerous Committees, and the men we have under arms will compel a Strict Observation of the general Association, tho’ few I believe will dare to attempt a violation of that solemn Compact.” Nearly 10,000 militia protected Maryland and Virginia, he continued, but only in a defensive manner. Most likely, the “tools of Administration” would label these colonials “seditious, Rebellious, Unconstitutional,” etc., but nothing could be further from the truth. Far from violating the English constitution, such measures in the colonies were invoking, reestablishing, and defending the traditional constitution.

Parliament had been founded to protect the constitution from the excesses of the king, but it was currently failing in this job. Drawing on relatively recent history, Carroll wrote that “James the 2ds. infractions of the Constitution were not so dangerous and alarming as the present.” In the 17th century, only the monarchy challenged the constitution, but the constitution was “now sapped by the very Body which was instituted for its defence.” Citing Bolingbroke as his philosophical authority, Carroll laid responsibility for the subversion of the English constitution not on the patriots of the American colonies, but on Parliament. When the colonies had protested abuses in government through the proper institutions—the colonial assemblies—Parliament had ignored them. Instead, the British government as a whole had promoted the power of the governors at the expense of the indigenous assemblies.

Without any real choice, Carroll believed, the various extralegal conventions, committees, associations, and militias of the American patriots in 1775 stood as the only real protectors of the English constitution, now controlled by designing men who loved “new fangled Devices, unthought of, or perhaps despised by your Ancestors as ungenerous and impolitic.”14 Carroll ended his letter to Graves by quoting Joseph Addison’s play, Cato: A Tragedy, an extremely popular 18th century play about the meaning of republican liberty and the necessity of sacrifice to combat tyranny.

Carroll also aired his views very publicly—though under the pseudonym “CX”—and importantly in the spring of 1776 in two long articles in the pages of the Baltimore newspaper Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette. The articles reveal much about Carroll’s historical and political views and are worth considering and quoting at length. By the time Carroll wrote these articles, he had served in several important roles as an elected representative in the Maryland Convention, and the Continental Congress had invited him to be a diplomat to Canada. Each article is well-written and well-argued.

The first article, printed on March 26, 1776, encouraged the people of Maryland to accept independence from Great Britain and the need for a new government as inevitable facts. Should men ignore these facts, necessity would force a new government on them, and consequently, with little time for reflection, the colonists might not adopt the best form of government. If, however, patriots accepted these facts, they would be in a better position to reflect on history and culture and adopt the best government possible. More practical than theoretical, the second article, published on April 2, 1776, criticized the current constitution of England as manifested in the colonies and argued for reform and the extralegal patriot Convention. Each article reflected and built upon the views he had advanced and defended as First Citizen in 1773.

At the beginning of his first article, Carroll quoted David Hume’s essay “The Idea of a Perfect Commonwealth,” noting that tradition and authority rather than an abstract Reason have governed the majority of men throughout history. Carroll quoted this not as a criticism, but as a statement of fact. Men of the 18th century, and specifically those influenced by the various enlightenments, might very well desire men to be governed primarily by Reason, but reality told a different story. For Reason to govern men and governments, it must be carefully cultivated in each generation and passed on to the following generations time and time again. In essence, then, a properly understood Reason is deeply cultivated, understood, and protected by tradition, education, and sacrifice. One could not simply assume that Reason would reveal itself unaided. Consequently, Carroll not so subtly implied, American patriots would have to rethink the nature of government and their relationship to it if they were to form a new commonwealth and be happy, especially if that commonwealth was to take seriously the notion of Reason.

Unlike John Locke, Carroll believed revolutions are not inevitable when governments become oppressive and destructive of the proper ends of man. Instead, men must overcome their own natures to reach true republican happiness. Such a reluctance to revolt also has a profoundly good side, however, as it prevents men from desiring unadulterated innovations in government. Such conservatism “restrains the violence of factions, prevents civil wars, and frequent revolutions; more destructive to the Commonwealth, than the grievances real, or pretended, which might otherwise have given birth to them.”15

Deeply attached to the English constitution, the colonists understandably mistook the forms for the essence. The English had offered mere pretense and deception: They might keep the forms of government and the language of virtue, but corruption had spread through all levels of government. When, therefore, corruption seems widespread and its continued corrosiveness inevitable, “all oaths of allegiance cease to be binding, and the parts attacked are at liberty to erect what government they think best suited to the temper of the people, and exigency of affairs.” Men have a right to rebel if their liberty and property are insecure, but they also—and more importantly—have a duty “to bring back the constitution to the purity of its original principles.”16 In the case of the American colonists, this would mean protection of liberty and property as understood through the Judeo-Christian, Greco–Roman, and Anglo–Saxon traditions.

For all intents and purposes, Carroll rightly noted, the colonists already understood self-governance. They had governed themselves for a considerable amount of time and had the habit, whether they understood this explicitly or not, of self-government. But Carroll believed that the extralegal Maryland Convention had numerous problems. Following Montesquieu, he criticized the concentration of legislative, executive, and judicial branches into one set of hands as constituting a form of despotism. Given the circumstances, he preferred a monarchy to an oligarchy, as “one tyrant is better than twenty.” Should the convention neglect “the true interest of the people” by failing to create a government with three separate branches, it could become as “obnoxious to the nation” as the Long Parliament did under Cromwell. Such was Carroll’s warning as he ended the first of his articles.

Published a week after the first, Carroll’s second article also began with a quote from Hume’s “The Idea of a Perfect Commonwealth” that set the tone for the entire article. A wise governor “will bear a reverence to what carries the marks of age; and though he may attempt some improvement for the public good, yet he will adjust his innovation, as much as possible, to the ancient fabric, and preserve entire the chief pillars and supports of the constitution.”17

Carroll proceeded to offer a number of suggestions for reforming the English constitution consistently with these “chief pillars and supports.” He continued in the same vein as in the previous article: Independence is coming, and Marylanders should prepare as soon as possible so as not to have necessity force a less than ideal government on them. They should follow Hume’s advice and, instead of remaking the English constitution, return to first principles and reform it. If the Marylanders succeeded, they would have created a more English constitution than the English currently enjoyed. Rooted in the principles of the past, a reformed constitution would also adopt the best in the science of government as understood historically and adapt to the particular needs of the province. Importantly, he believed independence would bring about a constitutional continuity, not a revolutionary overthrow of the constitution.

Carroll offered a number of criticisms of the current constitution and even more suggestions on how to reform it to respond to Maryland’s particular needs. As they reformed the constitution, bringing it back to first principles, Marylanders should recognize their possibilities as well as their limitations. It would not do, for example, to compare the relationship of the United Colonies to each colony to the relationship of Maryland to each of its counties. While each of the United Colonies was “separately independent” and thus in need of mechanisms to preserve this independence, the counties of Maryland should submit to a reformed legislature, recognizing “its jurisdiction [as] supreme.”

Not surprisingly, given the debates of 1773, Carroll claimed that the greatest threat to Maryland lay in the power of the executive under the current constitution. Sounding very much like First Citizen, CX argued that the executive wielded an inordinate power in the province, corrupting both the office and Maryland. Officers of the governor and court should not hold places in the upper or lower houses of the Assembly, he claimed, and the governor should not have the power to place or remove judges at his pleasure.

Carroll’s vision of government was rooted in the traditional notion of three branches representing monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy. Real power, he argued in a very Whiggish vein, should reside in the legislature; in an Aristotelian and aristocratic vein, he argued that this power should be concentrated specifically in the upper house of a bicameral legislature and that this upper house “should be composed of gentlemen of the first fortune and abilities in the Province” who “should hold their seats for life,” giving this chamber an aristocratic function. Counties would be equally represented—within limits—in the lower house. Time and experimentation would allow Maryland to find a proper mode of representation in the lower house, thus avoiding the “rotten boroughs” so infamous in the English Parliament. The governor and his council, he proposed, would be selected by the two houses on a year-to-year basis. No governor could serve more than three one-year terms. These suggestions would have the most influence on the shape of the Maryland Senate and, to a very limited degree, on the U.S. Senate.

Post-Independence

Carroll signed the Declaration of Independence proudly on August 2, 1776 (the official day for signing the document even though it had been adopted on July 4). During the Revolution, Carroll financially supported the Continental Army under George Washington as well as European officers who came to fight for the burgeoning republic. Additionally, he served in the Continental Congress, not only using his influence to support the army, but also attempting to stamp out the ever-growing corruption in the body. He also reportedly did what he could to recruit Irish immigrants to the United States during the war, hoping to increase the number of anti-English patriots.

Throughout the war, Carroll worried intensely about the concentration of power in the various Committees of Safety. They were necessary, he knew, as a transition from English government to permanent republican government; but no matter how democratic they might be, they were unhealthy over the long run because they concentrated power in a single body of power. When the war ended, Carroll supported the proposed federal Constitution as a means to separate the three functions of government into executive, legislative, and judicial.

As discussed at the 1787 Constitutional Convention and by James Madison in Federalist No. 63, the U.S. Senate was modeled after Maryland’s, itself a creation of Charles Carroll. In Carroll’s view, the Senate ought to combine the strengths of popular sovereignty, aristocracy, and monarchy in order to achieve the “protection of the lives, Liberty, & property of ye persons living under it.” Carroll continued:

The Govt. which is best adapted to fulfill these three great objects must be the best; and the Govt. bids fairest to protect lives, Liberty, & property of its citizens, Inhabitants, or subjects, [which is] founded on the broad basis of a common interest, & of which the sovereignty, being lodged in the Representatives of the People at large, unites the vigor & dispatch of monarchy with the steadiness, secrecy, & wisdom of an aristocracy.18

Although Carroll considered his primary role to be a promoter of stability in Maryland rather than in the United States, he did serve in the first U.S. Senate under the 1787 Constitution, and he gave away much of his property to allow the new country to establish its capital in what would become Washington, D.C. He also fought for hard money (rather than paper) and fervently defended the rights of Tories (those who remained loyal to Britain during the Revolution) to be treated as full Americans in their personal and property rights.

Though he definitely liked Thomas Jefferson on a personal level, Carroll believed Jefferson too radical to be a proper President and became one of Jefferson’s most ardent opponents in the early 19th century. “Mr. Jefferson is too theoretical and fanciful a statesman to direct with steadiness and prudence the affairs of this extensive and growing confederacy,” he wrote to Alexander Hamilton. Jefferson “might safely try his experiments, without much inconvenience, in the little Republick of San Marino, but his fantastic trickes would dissolve this Union.”19

Even worse in Carroll’s view, Jefferson as President would unleash all the latent French-style Jacobinism in the American republic. “I much fear that this country is doomed to great convulsions, changes, and calamities,” Carroll again lamented to Hamilton. “The turbulent and disorganizing spirit of Jacobinism, under the worn out disguise of equal liberty, and rights and division of property held out as a lure to the indolent, and needy, but not really intended to be executed, will introduce anarchy which will terminate, as in France, in military despotism.”20

Carroll’s fears proved untrue, of course, and as Jefferson’s reputation soared, Carroll’s dropped precipitously.

Though Carroll lived until November 14, 1832, he remained relatively silent throughout much of the last three decades of his life. However, he did meet with the greatest of 19th century French thinkers, Alexis de Tocqueville. The two, not surprisingly, got on well. Their conversation covered a number of topics, including the signing of the Declaration and the war for independence, government, and democracy. To Tocqueville, Carroll represented the end of a period in history. “This race of men is disappearing now after having provided America with her greatest spirits,” Tocqueville lamented. “With them the tradition of cultivated manners is lost; the people becoming enlightened, attainments spread, and a middling ability becomes common.”21

One can only wonder about Carroll’s influence on Tocqueville’s magisterial Democracy in America. Certainly, one finds at least a parallel to Carroll’s understanding of the dangers of democracy and the need for men of noble character—even a self-sacrificing aristocracy—in Volume Two’s chapter on “Why Democratic Nations Show a More Ardent and Enduring Love of Equality Than of Liberty.” “Men cannot enjoy political liberty unpurchased by some sacrifices,” Tocqueville wrote, “and they never obtain it without great exertions.” In concluding his discussion of Carroll, Tocqueville ruefully recorded that “[t]he striking talents, the great characters, are rare. Society is less brilliant and more prosperous.”22

When Charles Carroll of Carrollton passed away in November 1832, two headlines predominated in American papers: “A great man hath fallen in Israel” and “The Last of the Romans” has passed into eternity.

Selected Primary Writings

First CX Letter (March 26, 1776)23

“An established government has an infinite advantage by that very circumstance of its being established; the bulk of mankind being governed by authority, not reason; and never attributing authority to any thing, that has not the recommendation of antiquity.”

—Hume’s Essays, Idea of a Perf. Commonwea[l]th.

The foregoing observation of the judicious Essayist fully explains the cause of that reluctance, which most nations discover to innovations in their government: oppressions must be grievous and extensive, before the body of the people can be prevailed on to resist the established authority of the state; or the pernicious tendency of unexperienced measures very evident indeed, when opposed by considerable numbers. This proneness of mankind to obey the settled government, is productive of many benefits to society; it restrains the violence of factions, prevents civil wars, and frequent revolutions; more destructive to the Commonwealth, than the grievances real, or pretended, which might otherwise have given birth to them. Changes in the constitution ought not be lightly made; but when corruptions has long infected the legislative, and executive powers: when these pervert the public treasure to the worst of purposes, and fraudently [sic] combine to undermine the liberties of the people; if THEY tamely submit to such misgovernment, we may fairly conclude, the bulk of that people to be ripe for slavery. In this extremity, it is not only lawful, but it becomes the duty of all honest men, to unite in defense of their liberties; to use force, if force should be requisite; to suppress such enormities and to bring back the constitution to the purity of its original principles. If a nation, in the case put, may lawfully resist the established government; resistance solely is equally justifiable in an empire composed of several separate territories; to each of which, for securing liberty and property, legislative powers have been granted by compact, and long enjoyed by common consent; for should these powers be invaded, and attempted to be rendered nugatory and useless by the principal part of the empire, possessing a limited sovereignty over the whole; should this part relying on its superior strength and riches, reject the supplications of the injured, or treat them with contempt; and appeal from reason to the sword: then are the bands burst asunder, which held together, and united under one dominion these separate territories; a dissolution of the empire ensues; all oaths of allegiance cease to be binding, and the parts attacked are at liberty to erect what government they think best suited to the temper of the people, and exigency of affairs. The British North American Colonies are thus circumstanced:—they have then a right to chuse [sic] a constitution for themselves, and if the choice is delayed (should the contest continue) necessity will enforce that choice.—Whether it be prudent to wait till necessity shall compel these colonies to assume the forms, as well as the powers of government, shall be discussed in this paper.

That the United Colonies have already exercised the real powers of government, will not be denied: Why they should not assume the forms, no good reason can be given; as the controversy must NOW be decided by the sword! it may be said, that forms are unessential; if of so little consequence, why hesitate to give to every colony a COMPLEAT government? it has been suggested, that the inhabitants of this Province are not yet ripe for the alteration, and that they are still strongly attached to the subsisting constitution;—if they are so strongly attached to it, their attachment will continue, as long as the name and appearances of that constitution remain. The argument drawn from the affection of the people for the present constitution against the expediency of the proposed change at this time, will extend to any given period of time; and render the measure as improper THEN, as NOW. While our people consider the King of Great-Britain as THEIR King, while they wish to be connected with, and subordinate to Great Britain; while the notion remains impressed on their minds, that this connection and subordination are beneficial to themselves, we must not expect that unanimity, and those exertions of valour and perseverance, which distinguishes nations fighting in support of their independence. Confidence once betrayed and extinguished friendship can never be regained; the confidence of the colonies in, and their attachment to the Parent State arose from the interchange of benefits, and the conceived opinion of a sameness of interests; but now we plainly perceive that these are distinct; nay, incompatible: Why then should we consider ourselves any longer dependent on Great Britain, unless we mean to prefer slavery to liberty, or unconditional submission to independence? I by no means admit that the people are so much attached, as is alleged, to the present constitution: they are now fully convinced by facts too plain to be flossed over with ministerial arts; that the British government, on which the several provincial administrations immediately depend has for some years past aimed at a tyranny over these colonies. What security have they that some other attempt will not be made, should this be defeated? And before this security is obtained, or even proposed, to suppose an inclination in our people to run the hazard a second time of being enslaved, by the obstinately adhering to the present constitution; which in the end would inevitably lead them to their former dependence, and thus expose them to that hazard; is paying no great compliment to their understandings. For no other purpose are forms of a nominal, useless, and expensive government preserved, but that on a possible though very improbably compromise; the transition may be early and gentle from the present arrangements into the ordinary and customary course of administration. Is the advantage (and let the sticklers for the measure answer the question) any way equal to the risk? To suffer men to continue at the head of our communities, and in places of profit and trust, who are attached by interest, and conceive themselves to be found by the ties of oaths to the British government; is keeping up the remembrance of that subordination, which we should strive to obliterate since self-defence [sic], and the preservation of all we hold dear, seem NOW to be necessarily connected with our independence. It has been asserted, but not proved, that the people of this Province would dislike the abolition of the old, and the establishment of a new government, because they conceive the Convention to be already armed with too much power; and that this step would obstruct a reconciliation with Great Britain.—Were a compleat [sic] government to be framed, and the legislative, executive, and judicial functions distributed into different orders in the state; it is most certain, that the Convention so far from being thereby invested with ample powers, would deprive itself of part of those, which it now engrosses. What is it that constitutes despotism, but the assemblage and union of the legislative, executive, and judicial functions in the same person, or persons? When they are united in one person, a monarchy is established; when in many, an aristocracy, or oligarchy, both equally inconsistent with the liberties of the people: the absolute dominion of a single person is indeed preferable to the absolute dominion of many, as one tyrant is better than twenty. When the British ministry and senate are taught wisdom by experience; when they find that force will not effectuate what treaty may, they will offer terms of peace and reconciliation. If the former connection and dependence should be insisted on, and no security given to the colonies against the repetition of similar injuries, and similar attacks; would they act unwisely in rejecting the proposition? however, should a considerable majority entertain a different sentiment; a few placement under the new establishment, if inclined, will not have the power, I presume, to defeat the treaty. The interests of the people rightly understood, calls for the establishment of a regular and constituent government; and good policy should induce the Convention to consult the true interest of the people, by parting with the executive, and judicial powers, and placing them in different hands. By neglecting to do this, the long Parliament grew at last obnoxious to the nation.

There is nothing more natural (Dr. DAVENANT observes) than, for the commonality to love their own representatives, and to respect that authority, which by the constitution was established to protect their civil rights; and yet the Parliament in 1640, is an instance, that when the House of Commons took upon themselves the whole administration of affairs; the people grew as weary of them, as they had formerly been of State Ministers; and while they acted in this executive capacity, many of the multitude began to complain of their proceedings, question their privileges, and arraign their authority; for when collective bodies take in hand such affairs as were wont to be transacted by private men, mankind is apt to suspect they may be liable to those partialities, errors, or corruptions, of which particular persons may be accused in their management; so that it is possible for assemblies to become unpopular, as well as Ministers of State.

The Provincial Conventions, or Congresses have inadvertently pursued the very conduct they so justly condemn in the British Parliament, which has exceeded the limits prescribed by the constitution to its operations. The House of Commons was not instituted for the sole purpose of concurring with the other branches of the legislature in enacting laws, but to be a check also on bad ministers, to correct abuses, and to punish offenders too great for the ordinary courts of justice; in short the Commons were formerly not improperly [hailed?] the Grand Inquest of the nation:—But what are they now? Why a part of that very administration, they were by the original institution intended to control. The design the ministry in making parliament a partaker of, or indeed a principal in all their undertakings, is as evident, as it is pernicious to the public: for as the above quoted author remarks, “When the lawmakers transact the whole business of the State, for what can the ministers be accountable!” Besides the danger arising from the want of a proper check on the administration wherever the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government are blended together; these several powers in their nature distinct, and unfit to be trusted to the same persons, to interfere and clash with each other, that business is thereby greatly retarded; and the public of course considerably injured. For the truth of this assertion, I appeal to the last session of Convention the business of which might have been transacted in half the time, had not the attention of the members been distracted by the different capacities, they were constrained to act in, and taken up by matters very foreign from the duty of legislators. To those, who consider the subsisting forms of an useless government, as outward and insignificant signs power while the Convention grasps the solid substance, the above reasoning may appear to have little weight by such it must be objected, that Caesar in Rome, and Cromwell in England, without the name and pageantry of a King, governed as absolutely, as Tarquin the proud, or Henry VIII. If they should thus object, I will venture to pronounce, that they do not, or will not comprehend the force of the foregoing arguments. As perpetual dictator, Caesar was perpetual tyrant; Cromwell chose to rule the English nation, rather as Protector, than King; the prerogatives of the latter being defined, the powers of the former unknown. Having endeavoured to shew [sic] the expediency, if not the necessity of settling without delay a new government: I shall point out in my next paper, what alterations of the old one would render it, in my judgment, more perfect, and better adapted to our present, and probably future situation, and change of circumstances.

Second CX Letter (April 2, 1776)24

“To tamper, therefore, in this affair, or try prospects merely upon the credit of supposed arguments or philosophy can never be the part of a wise magistrate, who will bear a reverence to what carries the marks of age; and though he may attempt some improvement for the public good, yet he will adjust his innovation, as much as possible, to the ancient fabric, and preserve entire the chief pillars and supports of the constitution.”

—Hume’s Essays, Idea of a Perf. Commonwealth.

Our present government seems to be approaching fast to its dissolution; necessity during the war will introduce material changes; INDEPENDENCE, the consequence of victory, will perpetuate them. As innovations then must be made, let them be adjusted according to the advice of Mr. HUME, ‘as much as possible, to the ancient fabric.’ Let the spirit of our constitution be preserved; nay, improved by correcting the errors of our old system, and strengthening its soundest and best supports. I shall briefly mention, without the least design of censuring past transactions, or calling blame on any man, what appear to me defects in our present government; and shall attempt with great diffidence to point out the proper remedies.—The following are some of its defects:

The principal offices are too lucrative, and the persons enjoying them are members of the Upper House of Assembly. It is unnecessary, and be thought inordious [sic], to dwell on the mischiefs, which the Public has experienced in consequence of the misunderstanding between the two branches of the legislature, commonly occasioned by a difference of opinion respecting the fees of those offices. Much time has certainly been consumed in debates, and conferences, and messages on that subject, which could have been usefully employed in other matters. Is it proper that the same person should be both Governor, and Chancellor? The Judges of our Provincial Court hold their commissions during pleasure; the duties of their station are most important and fatiguing; the highest truth is reposed in them, yet how inadequate the recompence! The lessening of lucrative offices, and proportion the reward to the service in all; the exclusion of placemen from both Houses of Assembly; the separating the chancellorship from the chief magistracy; and the granting commissions to the judges of the Provincial Court, QUAM DIU SE BENE GESERRIT, with salaries annexed equal to the importance and fatigue of their functions; it is humbly conceived, would be alterations for the better in every instance.

The constitution of the Upper House seems defective also in this particular, That the members are removeable [sic] at the pleasure of the Lord Proprietary. To give to that branch of the legislature more weight, it should be composed of gentlemen of the first fortune and abilities in the Province; and they should hold their seats for life. An Upper House thus constituted would form some counterpoise to the democratical part of the legislature. Although it is confessed, that even then the democracy would be the preponderating weight in the scales of this government. The Lower House wants a more equal representation, to make it as perfect as it should be. At present, one third of the electors sends more delegates to the Assembly than the remaining two thirds. It will not be contended, I presume, that what has always been deemed a capital fault in the English Constitution is not one in ours, formed upon that model? Every writer in speaking of the defects of the former, reckons the unequal representation of the commonality among the principal. The Boroughs are proverbially stiled the rotten part of the constitution, on account of their venality, proceeding from the inconsiderable number of electors in most of them. If the people of this Province are not fairly and equally represented; no doubt, in the new modeling of our constitution, great care will be taken to make the representation as equal as possible. Before I proceed to point out a method for facilitating this desirable reform; I shall state some objections which have been used against the measure, and endeavour to give a satisfactory answer to each of them—

A new representation will offend those counties which now send to the Assembly a greater number of Delegates, than their just proportion; hence divisions will ensue, at all times to be dreaded, but most in the present. Is the proposed alteration just or not! If just, then they only should be esteemed sowers of division, who oppose it. But should such a representation take place, more Delegates would be chosen in some counties, then in others, and should the votes be collected individually on all questions as heretofore practiced, they might frequently be carried against the smaller counties. What is that but saying that the majority would determine every question, the only mode of decision that can with any propriety be adopted? The Colonies vote by Colonies in Congress, therefore counties ought to vote by counties in Convention; and therefore it is useless to alter the representation, or to have more delegates from one country than another. The force of this reasoning, if there be any in it, I could never comprehend. The colonies are separately independent, and to preserve this independency, it may perhaps, be necessary to vote by colonies in Congress, but surely it will not be said that the counties of Maryland are thus independent, or that there are as many little independent principalities in the Province as there are counties? All our counties are subject to the same legislature, which within the territory owning its jurisdiction, is supreme. The inconveniences that may arise from the colonies voting by colonies in Congress must be imputed to the jealousy of Independence; or to use a softer term, to the necessity of securing to each colony its own peculiar government. To reconcile the strength, safety, and welfare of all the United Colonies, with the entire privileges, and full independency of each, requires a much great share of political knowledge, than I am made of. But if this imperfection in the general constitution or confederation of the colonies, can not be remedied, does it follow, that the same imperfection should run through the particular constitutions of every colony, or be retained in that of any one? Different colonies may possibly, in process of time have different interests; and to secure to each Colony its peculiar and local interests; it may be thought most prudent to establish independence of each on a permanent basis. Have the two shores of Maryland, or can they have[,] a difference of interests? Should they be really so distinct, as to warrant the suspicion that the lesser part would be sacrificed to the greater; then are they unfit to be connected under one government; a separation ought to take place, to terminate the competition and rivalship, which this diversity of views and interests would produce; and all the consequent evils of two powerful and opposite factions in the same state. The interests of the two shores are the same; in the imagination of some men a difference may indeed exist, but not in reality. Is the welfare then of the whole Province to be sacrificed to the whims, the caprice, the humours [sic], and the groundless jealousy of individuals, not constituting a twentieth part of the people? Let those, who would oppose an equal representation on a supposed contrariety the IPSE DIXIT of no man, or set of men ought to prevail against a reform of the representative, so consentaneous to the spirit of our constitution.

To come at a fair and equal representation of the whole people, the following method is proposed.

Let the Province be divided into districts, merely for the purpose of elections, containing each one thousand voters, or nearly that number; let every district elect [_____] representatives: suppose, for instance, the whole number of electors should amount to 40,000, then if every 1000 should elect two Representatives, there would be 80 Representatives returned to Assembly. For facilitating the divisions of the counties into districts, and for the ease and convenience of the inhabitants in other respects such counties as are too large, may be divided into one or more, according to their respective extent. As our people will in all likelihood greatly increase in the course of fifty or sixty years it may be necessary in order to correct the inequalities which that lapse of time will probably occasion in the representatives to new-model the elections, preserving the same number of Delegates to Assembly, it may be ordained that 1500 return two only. If this precaution be not taken, the representative may in time become too numerous and unweildy [sic]; a medium should be preserved between a too small and a too large Senate; the former is more liable to the influence of a separate interest from that of their constituents and combination against that interest, the latter unfit for deliberation and mature counsels. ‘Every numerous assembly (Cardinal de Retz observes) is [a] mob, and swayed in their debates by the least motives; consequently every thing there depends upon instantaneous turns.” When the Province shall contain as many inhabitants as it will be capable of supporting in its most improved state of cultivation, it will not even then be advisable to suffer the representative to exceed one hundred for the reasons assigned. If the Delegates should ever amount to that number, to preserve a due proportion between the two houses, the members of the Upper House ought to be encreased to eighteen or nineteen. It would add to their importance, and give them more weight in the government, if on all vacancies they were to chuse [sic] their own members. The above alterations of our constitution are no ways inconsistent with a dependence on the crown of Great Britain, and therefore, not justly liable to the censure and opposition of those who wish the colonies to continue dependent.

During the civil war the appointment of a Governor and Privy Council, not to exceed five, must be left to the two Houses of Assembly; and if we should separate from Great Britain, the appointment must remain with them. The Governor and Council are to be entrusted with the whole executive department of government, and accountable for their misconduct to the two houses. A continuance of power in the same hands is dangerous to liberty; let a rotation therefore be settled to obviate that danger yet not so quickly made, as to prove detrimental to the State by frequently throwing men of the greatest abilities out of public employments. Where would be the inconvenience if the Governor and Privy Council were annually elected by the two Houses of Assembly, and a power given by the constitution to those Houses of continuing them in office from year to year, provided that their continuance should never extend[] beyond the term of three successive years?

A variety of other arrangements scarcely less important, must follow the proposed changes; only the outline of the constitution is drawn, the more intricate parts, “their nice conections [sic], just dependencies” remain to be adjusted by abler heads. A long dissertation was not intended, a minute detail would be tiresome; and perhaps the author may be justly accused of having already trespassed on the patience of the Public.

Recommended Readings

- Thomas O’Brien Hanley, S.J., ed., The Charles Carroll Papers (Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources, 1972).

- Kate Mason Rowland, The Life of Charles Carroll of Carrollton, 1737–1832: With His Correspondence and Public Papers, 2 Vols. (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1898).

- Bradley J. Birzer, American Cicero: The Life of Charles Carroll (Wilmington, DE: ISI Books, 2010).

- Ronald Hoffman, Princes of Ireland, Planters of Maryland: A Carroll Saga, 1500–1782 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2000).

- Pauline Maier, The Old Revolutionaries: Political Lives in the Age of Samuel Adams (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1980).

- Scott McDermott, Charles Carroll of Carrollton: Faithful Revolutionary (New York: Scepter, 2002).

Notes

[1] Alexis de Tocqueville, Journey to America, ed. J. P. Mayer (London: Faber and Faber, 1959), p. 86.

[2] “Ratio Studiorum,” New Advent, The Catholic Encyclopedia, https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/12654a.htm (accessed May 16, 2025).

[3] John Jenison to Charles Carroll of Annapolis, November 1753, in Dear Papa, Dear Charley: The Peregrinations of a Revolutionary Aristocrat, as Told by Charles Carroll of Carrollton and His Father, Charles Carroll of Annapolis, Vol. 1, ed. Ronald Hoffman et al. (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), pp. 23 and 24.

[4] Peter S. Onuf, ed., Maryland and the Empire, 1773: The Antilon–First Citizen Letters (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1974), pp. 206–207.

[5] Ibid., p. 197.

[6] Ibid., p. 217.

[7] Ibid., p. 207.

[8] Maryland Gazette, June 2, 1774, https://msa.maryland.gov/msa/stagser/s1259/121/5912/pdf/p5912010.pdf (accessed May 19, 2025). See also “Coercive Acts by British Parliament,” 1774, Ashbrook Center at Ashland University, Teaching American History, https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/coercive-acts/ (accessed May 19, 2025).

[9] William Eddis, Letters from America, ed. Aubrey C. Land (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1969), pp. 85–87. Emphasis in original.

[10] Proceedings of the Conventions of the Province of Maryland Held at the City of Annapolis in 1774, 1775, & 1776 (Baltimore: James Lucas & E. K. Deaver; Annapolis: Jonas Green, 1836), p. 3, https://ia601305.us.archive.org/11/items/proceedingsofcon00mary/proceedingsofcon00mary.pdf (accessed May 19, 2025).

[11] Ibid., p. 5.

[12] Mercy Otis Warren, History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution, ed. Lester H. Cohen (Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund, 1994 [1805]), Vol. I, p. 77, https://oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/815/0025.01_Bk.pdf (accessed May 19, 2025).

[13] Charles Carroll to William Graves, August 15, 1774, in Dear Papa, Dear Charley, Vol. 2, pp. 747–727.

[14] Charles Carroll to William Graves, February 10, 1775, in ibid., pp. 786–789.

[15] Charles Carroll of Carrollton as “CX,” Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette, or the Baltimore General Advertiser, March 26, 1776.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Carroll as “CX,” Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette, April 2, 1776.

[18] Carroll, defending ratification of the 1787 Constitution, in “An Undelivered Defense of a Winning Cause: Charles Carroll of Carrollton’s ‘Remarks on the Proposed Federal Constitution,’” Maryland Historical Magazine, Vol. 71, No. 2 (Summer 1976), p. 231.

[19] “To Alexander Hamilton from Charles Carroll of Carrollton, 18 April 1800,” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-24-02-0338 (accessed May 17, 2025).

[20] “To Alexander Hamilton from Charles Carroll of Carrollton, 27 August 1800,” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-25-02-0071 (accessed May 17, 2025).

[21] Tocqueville, Journey to America, p. 86.

[22] Ibid., pp. 86–87.

[23] Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette, or the Baltimore General Advertiser, March 26, 1776, reprinted in “Charles Carroll of Carrollton’s First CX Letter,” Stormfields Blog, posted February 19, 2014, https://bradbirzer.com/2014/02/19/charles-carroll-of-carrolltons-first-cx-letter/ (accessed May 17, 2025). Emphasis and punctuation as in original.

[24] Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette; or, the Baltimore General Advertiser, April 2, 1776, reprinted in “Charles Carroll of Carrollton’s Second CX Letter,” Stormfields Blog, posted February 19, 2014, https://bradbirzer.com/2014/02/19/charles-carroll-of-carrolltons-second-cx-letter/ (accessed May 17, 2025). Emphasis and punctuation as in original.