—Daniel Webster, March 10, 18311

Life

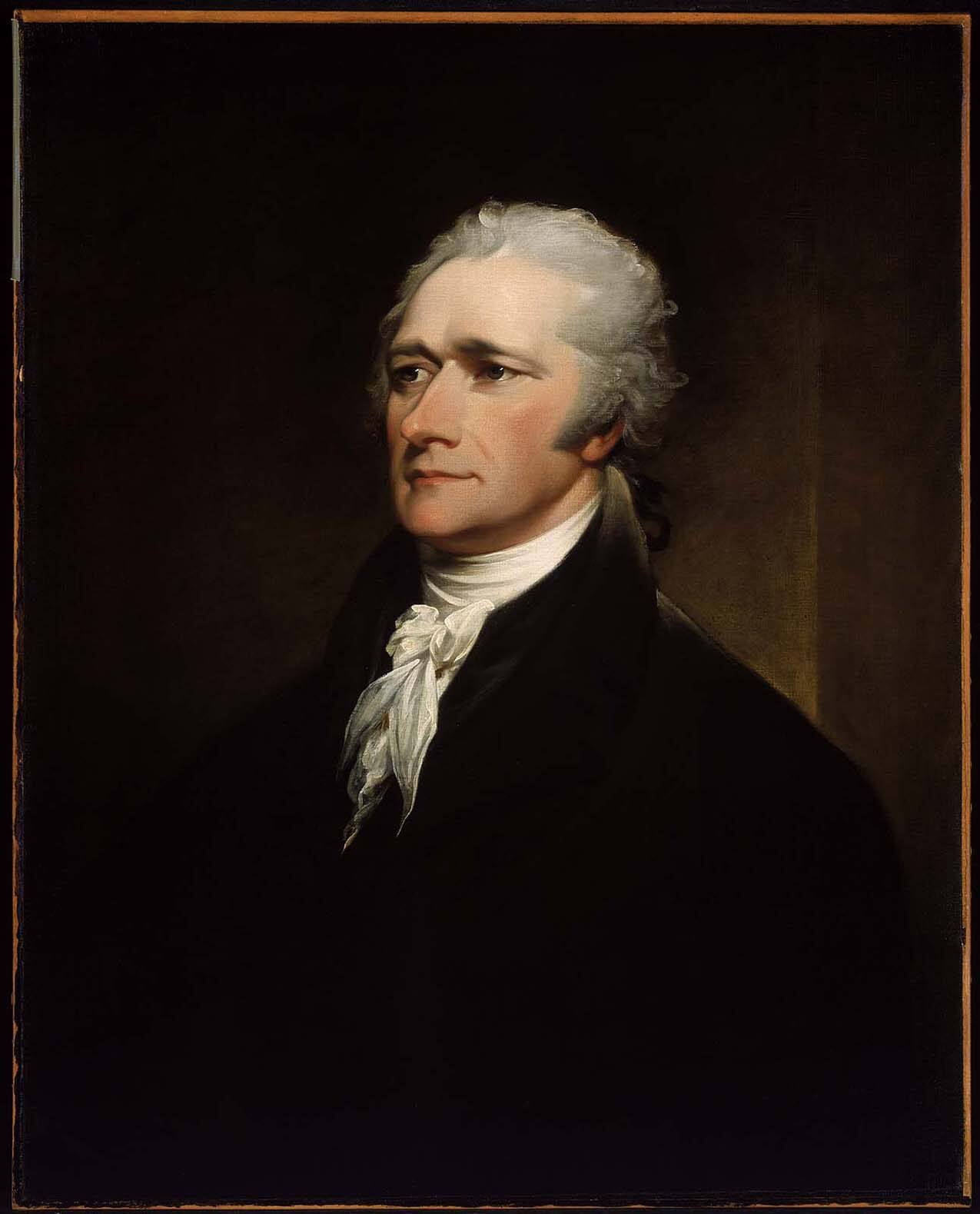

Alexander Hamilton was born January 11, 1757, on the island of Nevis in the British West Indies and later moved to St. Croix. He was the son of Scottish merchant James Alexander Hamilton and Rachel Fawcett Lavien. After working as a clerk for a St. Croix trading post, he immigrated to America in 1772. At the age of 25, Hamilton married Elizabeth Schuyler on December 14, 1780. They had eight children: Philip Hamilton (1782); Angelica Hamilton (1784); Alexander Hamilton Jr. (1786); James Alexander Hamilton (1788); John Church Hamilton (1792); William Stephen Hamilton (1797); Eliza Hamilton (1799); and Philip Hamilton (1802). Hamilton died on July 12, 1804, in New York City after being fatally wounded in a duel with Aaron Burr and is buried in Trinity Churchyard in Manhattan.

Education

Hamilton attended grammar school in Elizabethtown, New Jersey, and graduated from King’s College (now Columbia University) in 1775.

Religion

Presbyterian

Political Affiliation

Federalist

Highlights and Accomplishments

1776: Captain, New York Artillery Company

1777–1781: Lieutenant Colonel and Aide de Camp to George Washington

1781: Commander of Infantry Brigade at the Battle of Yorktown

1783–1804: Practicing Attorney in New York

1782–1783, 1788: Delegate to the Continental Congress

1784: Founder and Director, Bank of New York

1786: Delegate to the Annapolis Convention

1775: Delegate to the Second Continental Congress

1787: Member, New York State Assembly

1787: Delegate to the Constitutional Convention

1787–1788: Co-author, The Federalist Papers

1789–1795: Secretary of the Treasury

1798: Inspector General of the Army

1801: Founder, New York Evening Post

Of all the Founders of the American Republic, Alexander Hamilton is the one whose reputation has fluctuated the most. During his lifetime, Hamilton had committed defenders as well as passionate detractors. During the antebellum period, his reputation declined, but after the Civil War, with the triumph of neo-Federalism, he became one of the most honored in the national pantheon.

Today, Hamilton’s reputation depends largely on one’s political orientation. Liberals consider him (despite his humble origins) too elitist, a mouthpiece for the rich and well-born, and a militarist. Conservatives often dismiss him as an anti–free trade protectionist and the forefather of national industrial policy (the idea that government can do a better job of picking eventual winners and losers in the economy than markets can do). Both sides are wrong. Hamilton deserves to be honored for the critical role he played in three important areas: constitutional government, political economy and public finance, and national defense.

The Life of Alexander Hamilton

Hamilton probably was born in 1757—the record is not clear—on the British West Indian island of Nevis and later moved with his family to St. Croix. As a teenager, the precocious Hamilton favorably impressed his employer Nicholas Cruger and the Reverend Hugh Knox, a Presbyterian minister, who in 1772 conspired to send the 15-year-old to North America for an education. Hamilton matriculated at King’s College (now Columbia University) in New York.

Hamilton became involved in the pre-Revolutionary politics of King’s College in particular and New York in general. In the winter of 1774–1775, he anonymously wrote two pamphlets, A Full Vindication of the Measures of Congress from the Calumnies of Their Enemies and The Farmer Refuted, in response to popular Loyalist writings. As the Patriot cause spread, Hamilton joined a Patriot drill company, and in March 1776, he was made captain of a New York artillery battery. He served in this capacity through the summer and fall as the British maneuvered George Washington’s Continental Army out of New York and pursued it south across New Jersey. His artillery saw action at both Trenton and Princeton. Two months after the Battle of Princeton, Hamilton was promoted to lieutenant colonel and became an aide to George Washington. He served in this role for four years, forging a relationship with Washington that would have immense consequences for the new nation.

In the summer of 1781, Washington gave Hamilton command of an infantry brigade. He saw action at Yorktown, which included leading his brigade in a nighttime attack on a key British trench line. Washington praised Hamilton and his men for their “intrepidity, coolness and firmness” during the action.

The British surrendered at Yorktown on October 19, 1781. Although the war would not officially end for another two years, Hamilton was able to return to his family in New York and take up the study of law in Albany. In November 1782, the New York Assembly chose Hamilton to be a delegate to Congress where he first met James Madison, who would be both ally and adversary over the next two decades. A series of events that culminated with Congress fleeing to New Jersey when a group of disaffected soldiers marched on Philadelphia convinced Hamilton that the national legislature was a weak and debilitated body. Hamilton resigned from Congress and returned to his family and the law.

In September 1786, the New York Assembly chose Hamilton to be a delegate to the Annapolis Convention, and in March 1787, he was selected to attend the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia. His contributions to the actual drafting of the Constitution were fairly limited and far less important than his truly Herculean efforts to gain New York’s ratification of the final document.

Hamilton turned first to the press, collaborating with John Jay and James Madison to write The Federalist (commonly referred to today as The Federalist Papers), a series of newspaper essays under the Plutarchian pseudonym of Publius. Of the 85 essays comprising The Federalist, Hamilton wrote more than two-thirds, mostly on war and foreign policy, the law, executive power, and the administration of government. During the New York Ratifying Convention, Hamilton was virtually a one-man show, making numerous powerful speeches over the course of the convention that successfully swayed many Anti-Federalist opponents to support the new government. By a close vote, New York agreed to ratification in July 1788, making it the 11th state to adopt the new Constitution.

When the new government met in New York City during the spring of 1789, President Washington chose Hamilton as the first Secretary of the Treasury. The Senate confirmed his nomination in September 1789, and he immediately set to work to establish America’s credit by resolving the problem of the country’s outstanding debt. As Secretary of the Treasury, Hamilton presented three important reports to the new Congress on behalf of the Washington Administration. His Report on the Public Credit provided for funding the national and foreign debts of the United States as well as for federal assumption of the states’ Revolutionary War debts. Hamilton’s next major project was to establish a national bank, a means for fulfilling the government’s powers in the event of an emergency such as war. His Report on a National Bank was delivered in December 1790, and a bill chartering such a bank was passed by Congress fairly quickly. Madison questioned the constitutionality of a national bank, but Hamilton made a powerful argument for its constitutionality—based on the “implied powers” of the Constitution—and Washington signed the bank bill into law early in 1791. Hamilton then immediately set to work on his third great project, a Report on the Subject of Manufactures, which he delivered to Congress at the end of that year.

Hamilton’s financial program was a cause of great concern for Thomas Jefferson and his allies. In the tradition of the Radical Whigs, they saw its measures as an instrument of monarchy and corruption, at odds with the yeoman virtues necessary for the young Republic. Disputes between Hamilton and Jefferson exploded into public view in the “newspaper war” of 1792. Their quarrel over finances was exacerbated by a difference of opinion regarding the French Revolution. Jefferson thought the United States should assist France against Britain out of “gratitude” for its assistance to America during its own revolution, while Hamilton favored closer ties with Great Britain and believed America should remain neutral. Washington concurred with Hamilton and issued his Neutrality Proclamation.

Jefferson left the Cabinet at the end of 1793, frustrated by Hamilton’s influence. Following the crisis of the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794, Hamilton also left to return to private life, but the furor over the Jay Treaty led him to enter the fray once more in a series of newspaper essays titled “The Defence” under the pen name of Camillus. Hamilton’s final service to Washington was his assistance in drafting his Farewell Address, the outgoing President’s call for America to preserve the Union.

In the election of 1796, Hamilton worked assiduously to prevent Jefferson from becoming President by attempting to ensure that federal electors in New England cast their votes for Thomas Pinckney as well as John Adams. Adams interpreted this strategy as an attempt to influence the election in favor of Pinckney rather than him. This episode, along with Hamilton’s influence over Adams’s Cabinet, led to a falling out between the two that would severely weaken the Federalist Party and contribute to its defeat in the election of 1800.

Although Hamilton would never hold public office again, he remained politically active. He returned to New York to practice law and to found the New York Evening Post.

Constitutional Order

Hamilton, like Jefferson and most of the Founding generation, saw the American Revolution as an act of deliberation designed to secure the natural rights enumerated in the Declaration of Independence: “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” However, a revolution can unleash a lawless spirit in a people. Men must “dissolve [existing] political bands” before they can establish a new form of government that is more congenial to rights and liberty, and revolutionary fervor is not conducive to a stable political society—even one that is intended to protect individual rights.

Hamilton understood that a passion for liberty was necessary if the cause of American independence was to succeed, but he also understood that this passion ultimately had to be tempered by the rule of law. As he said during the New York Ratifying Convention in 1788,

In the commencement of a revolution…nothing was more natural, than that the public mind should be influenced by an extreme spirit of jealousy…and to nourish this spirit, was the great object of all our public and private institutions. The zeal for liberty became predominant and excessive. In forming our confederation, this passion alone seemed to actuate us, and we appear to have had no other view than to secure ourselves from despotism. The object certainly was a valuable one…. But, Sir, there is another object, equally important, and which our enthusiasm rendered us little capable of regarding. I mean the principle of strength and stability in the organization of our government, and vigor in its operations.2

The problem is that the passions released in the fight for one’s rights can destroy those rights. Ultimately, individual rights can be preserved only when a strong sense of “law-abidingness exists in society.” Hamilton was appalled at the call for “permanent revolution” that characterized Jefferson’s rhetoric. He believed that Jefferson’s complacent and bookish reaction to Shays’ Rebellion (“I hold it that a little rebellion now and then is a good thing”) and the French Revolution (“The Tree of Liberty must be watered from time to time with the blood of tyrants”) was a recipe for disaster that would ensure “frequent tumults” instead of good government. The answer was to make Americans law-abiding by attaching them to their Constitution, which, although their own creation, binds them by its constraints while it is in force.

Attaching the people to the Constitution’s rule of law would preserve the new government as if it were an ancient establishment, promoting the stable administration of justice without which the protection of our rights—the object of the Revolution—could not be assured. Hamilton sought by speech and deed to moderate the passions of the people and attach them first to their state constitutions and then to the federal Constitution. Examples of how Hamilton sought to build this attachment included his legal defense of New York Loyalists after the Revolution (along with his Phocion letters on the same topic);3 his defense of the new Constitution during the ratification debates of 1787–1788; his activities as Secretary of the Treasury to teach Americans the necessity of paying their debts and keeping contracts; and his efforts as a member of Washington’s Cabinet to subordinate American gratitude to France and the passion of Americans for the French Revolution to the dictates of international law.

Nothing indicates Hamilton’s purpose in moderating revolutionary passions better than a letter he wrote to John Jay at nearly the same time that he was writing his own revolutionary pamphlets:

The same state of passions which fits the multitude…for opposition to tyranny and oppression, very naturally leads them to contempt and disregard of all authority…. When the minds of those are loosened from their attachment to ancient establishments and courses, they seem to grow giddy and are apt more or less to run into anarchy.4

Hamilton’s concern about the need for lawfulness in a republic also helps to explain his views on immigration. Although Hamilton was himself an immigrant, he was adamantly opposed to the open immigration policies that President Thomas Jefferson proposed in his first annual message to Congress in 1801. The incoming President had once opposed unlimited immigration but now saw it as a way to secure the future political dominance of his own party over Hamilton’s Federalists.

Like most Federalists, Hamilton was concerned about French influence on American politics. The French Revolution had descended into terror and led to the rise of Napoleon, yet Jefferson and his Republican Party persisted in their attachment to the French. Hamilton feared that Jefferson’s proposal for unlimited immigration would lead to the triumph of the radical principles of the French Revolution over those of the more moderate American Revolution. Writing as Lucius Crassus, Hamilton argued that:

The safety of a republic depends essentially on the energy of a common national sentiment; on a uniformity of principles and habits; on the exemption of the citizens from foreign bias, and prejudice; and on that love of country which will almost invariably be found to be closely connected with birth, education, and family.5

Invoking Jefferson’s own Notes on the State of Virginia, Hamilton expressed concern that immigrants would import illiberal views. He continued: “[I]t is unlikely that they will bring with them that temperate love of liberty, so essential to real republicanism.” Hamilton concluded that “[t]o admit foreigners indiscriminately to the rights of citizens, the moment they put foot in our country, as recommended in [Jefferson’s] message, would be nothing less than to admit the Grecian horse into the citadel of our liberty and sovereignty.” In other words, a large number of immigrants attached to the principles of the French rather than the American Revolution would undermine that “temperate love of liberty” essential to republican government.

Political Economy

Alexander Hamilton played an important role in laying the foundation for America’s young market economy and encouraging the entrepreneurship that would be at the forefront of America’s economic growth. As the first Secretary of the Treasury, he set the conditions for the United States’ future prosperity and economic success by establishing the nation’s credit, which provided an incentive for individuals and nations alike to invest in America.

In 1790, the United States faced what seemed to be insuperable barriers to financial stability. The new nation owed vast sums to its citizens and to foreign creditors. It was behind in both principal and interest payments and lacked the means to raise the necessary revenues. As a result, the credit of the United States was held in low esteem, which meant that no one would be willing to lend money to America unless a substantial “risk premium” was added. The American economy was weak, and its financial future was unclear, making large-scale investment and long-term prosperity unlikely.

Some called for repudiation of the domestic portion of the debt; others called for a scaled-down version of repudiation—“discrimination” between original holders and present holders of debt, which would punish “speculators.” Still others demanded that the government pay its debt precisely according to the terms set down. Hamilton proposed that the federal government “assume” the debts of the Confederation (as well as the war debts of the individual states) and pay them over time. Such a course would lead to eventual retirement of the debt in an orderly manner and in a way that would “monetize” it, making significant additional capital available for new investment. “The proper funding of the present debt [would] render it a national blessing,” said Hamilton.6 Allowing for the regular payment of interest while keeping the principal more or less intact would serve as the basis for a uniform and elastic currency. This would make future credit available as quickly as possible, facilitating economic growth and stability.

Hamilton knew that a creditworthy America would generate vast quantities of capital from both domestic and foreign investors. Credit, as the word itself indicates, depends on trust and faith, which must be earned in the marketplace. To earn credit, a country must show that it will honor long-term commitments and keep its financial obligations—both of which are necessary for stable economic transactions.

His financial plan also reinforced his goal of making Americans law-abiding: By emphasizing that the country must pay its debt, he reminded citizens of the moral importance of paying their debts. The assumption of the states’ debts by the national government had the additional benefit of strengthening ties to the new government, thereby further cementing the Union. Hamilton believed that the establishment of justice and creation of a law-abiding and virtuous people required habituation to virtue and that paying one’s debts, both private and public, played an important role in achieving such habituation. As he wrote in Federalist No. 72, “the best security for the fidelity of mankind is to make their interests coincide with their duty.”7

The second element of Hamilton’s grand plan was to stimulate the growth of domestic manufactures. Rejecting the common assumption that America could prosper with just an agricultural base, he argued that the new nation should concentrate on developing its small-business entrepreneurs. However, his strategy was not to assist domestic industry through state control of the market. Hamilton was neither a mercantilist nor a protectionist. He envisioned the role of government as using limited bounties or subsidies (contingent on a surplus of revenue) to help infant American industries overcome barriers to entry erected by the existing terms of trade. His advocacy of limited tariffs was not to advantage particular manufactures, but to yield customs revenues, then the leading source of government funds. In general, Hamilton maintained that trade was directed by its own natural rules and for the most part best left alone. He considered it the role of government to create a stable framework that would allow the free market to operate and prosper.

Hamilton wanted to affect the very nature of the American economy and arouse a dynamic liberty of industriousness, enterprise, and innovation. He envisioned a nation in which freedom to engage in all manner of enterprises would give citizens of differing aptitudes the chance to achieve happiness, and he saw commerce as a positive good that would make citizens more fully human by stimulating the intellect, the most characteristic possession of man. Manufactures would give “greater scope for the diversity of talents and dispositions, which discriminate men from each other.”

In his Report on the Subject of Manufactures, Hamilton argued that a diverse economy develops society:

The spirit of enterprise…must be less in a nation of mere cultivators, than in a nation of cultivators and merchants; less in a nation of cultivators and merchants, than in a nation of cultivators, artificers, and merchants.… Every new scene, which is opened to the busy nature of man to rouse and exert itself, is the addition of a new energy to the general stock of effort.8

Rather than distributing its rewards based on conventional distinctions such as birth or wealth, the United States would distribute them in accordance with ability and republican virtue. To do this, it was necessary to create a free, commercial republic that rewarded merit and ambition.

Hamilton understood that commerce and a market economy provide prosperity and growth without which, as history has shown, no free government can exist. Prosperity is necessary to create the military and naval power needed to sustain a regime capable of protecting the natural rights of its citizens. He also knew that liberty and the economic diversity and human excellence that flow from it depend on a government that is strong enough to protect it and confident enough to allow each individual to flourish. As Hamilton wrote in the Report on Manufactures:

It is a just observation, that minds of the strongest and most active powers…fall below mediocrity and labour without effect, if confined to uncongenial pursuits. And it is thence to be inferred, that the results of human exertion may be immensely increased by diversifying its objects. When all the different kinds of industry obtain in a community, each individual can find his proper element, and can call into activity the whole vigour of his nature.9

Such an environment is hospitable to great men, to captains of industry, to seekers after honor and fame. A great nation based on equal political rights in which merit, as opposed to status, is the basis for reward provides the greatest opportunities for those who are motivated by the “love of fame, the ruling passion of the noblest minds….”10

National Defense

Throughout history, war has been the great destroyer of free government: The necessities, accidents, and passions of war tend to undermine liberty. The unprecedented ability of the United States to wage war while still preserving liberty is a legacy of Alexander Hamilton, who deserves much credit for the institutions that have enabled the United States to minimize the inevitable tension between the necessities of war and the requirements of free government. This, of course, is not the conventional view of Hamilton. Contemporaries such as Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and John Adams saw Hamilton as a Caesar or a Bonaparte, bent on tyranny at home and conquest abroad. Unfortunately, many recent historians also accept this false view.

Hamilton was a soldier-statesman who demonstrated that he could be trusted with the sword of his country. Rejecting the utopian vision of Jefferson and many of his allies, Hamilton was what today is called a realist, one who understands that war is a fact of international life. Accordingly, he believed that the survival of the infant Republic depended on developing and maintaining the potential to make war. Far from being a militaristic state-builder along the lines of Frederick the Great or Otto von Bismarck, Hamilton was an advocate of limited government and understood the necessity of remaining within the legal bounds established by the Constitution. “Let us not establish a tyranny,” he wrote to Oliver Wolcott in 1798. “Energy is a very different thing from violence.” He was a strategist before the word was coined, and his strategic objectives were to enable the American Republic to avoid war when possible and wage it effectively when necessary, all the while preserving both political and civil liberty.

Hamilton had to contend with several popular views that denigrated foreign affairs and national security—views that have their counterparts today. The first was the uncritical belief that economic progress and commerce would not only improve the material conditions of life, but also change human nature sufficiently to make war a thing of the past. The second was a corollary of the first: that a focus on domestic affairs alone was the key to peace and prosperity. As a realist, Hamilton understood that force ruled relations among nations and that this was as true in the New World as it had been in the Old. He hoped that if America could survive its infancy as an independent nation, consent might replace force in the New World, but he also understood that for the foreseeable future, the volatile and uncertain geopolitical situation required that America take steps to defend itself, its rights, and its national honor.

The first step in making the United States secure was to create a powerful and indissoluble Union that could effectively discourage war on the North American continent, thus avoiding the militarization that led to the downfall of earlier free governments. Hamilton’s support for the Constitution was based largely on his belief that only such a Union could ensure American security at home and project unity abroad.

The second step was to ensure that the nation had the means to defend itself in a hostile world. These included not only the establishment of credit, creation of a national bank, and encouragement of manufactures, but also the development of a strong standing army and an ocean-going navy. Hamilton emphasized the ability to defend the constitutional order itself, which was the necessary instrument for protecting thee liberty, happiness, and prosperity of its citizens. When it came to national defense, as he wrote in Federalist No. 23:

[The powers necessary to defend the Constitution] ought to exist without limitation, because it is impossible to foresee or define the extent and variety…of the means which may be necessary to satisfy them. The circumstances that endanger the safety of nations are infinite, and for this reason no constitutional shackles can wisely be imposed on the power to which the care of it is committed.11

This was essentially the view that Lincoln would adopt during the Civil War.

Hamilton’s concern for national defense and desire to provide for the national strength that would make its use of American military power less necessary (he was an early advocate of peace through strength) do much to explain why he supported a broad rather than a narrow construction of the Constitution, a strong rather than a weak executive, a standing army rather than a militia, and commerce and manufactures over an agricultural economy. In most of these controversies, Hamilton’s strategic sobriety prevailed, which accounts in large measure for the unprecedented ability of the United States to combine great power and a wide degree of liberty.

Hamilton’s Character

Two events in particular capture the essence of Hamilton’s character. The first is especially instructive for our day, and the second allows us a glimpse into Hamilton’s soul and unwavering dedication to the cause of his adopted country.

While serving as Secretary of the Treasury, Hamilton had an affair with Maria Reynolds, a married woman whose husband proceeded to blackmail him. When his political enemies accused him of serious financial improprieties, Hamilton wrote a pamphlet in which he publicly admitted to the extramarital affair, for which he expressed remorse, in order to refute the far more dangerous charge that he was accepting bribes. Hamilton understood the extent to which his political reputation was tied to the success of his financial plan, and thus to the early success of the new nation, and was willing to sacrifice his private reputation for the public good.

In 1800, an electoral tie between two Republican candidates, Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr, threw the election to the House of Representatives. John Adams had placed a distant third in the voting, and several Federalists made clear their intention to vote for Burr to deny Jefferson the presidency. Hamilton, despite his deep antipathy toward Jefferson, wrote a series of letters to several Federalists urging them to support Jefferson because he considered Burr to be a dangerously unprincipled adventurer. “In a word,” Hamilton wrote, “if we have an embryo-Caesar in the United States, ’tis Burr.”12 The Representatives in the House voted 35 times, and after each ballot, the votes were equally split between Jefferson and Burr. On the 36th ballot, one of the recipients of Hamilton’s letter-writing blizzard abstained, handing the election to Jefferson.

In 1804, disaffected New England Federalists hatched a plan to secede from the Union and convinced Burr to run for governor of New York and persuade his state to support their cause. Hamilton again did his best to thwart Burr’s ambitions. After this defeat, Burr challenged Hamilton to a duel, which Hamilton—like Cato, willing to die for the republic to prevent the triumph of a Caesar—felt obliged to accept. Although Hamilton was opposed to dueling—his eldest son Philip had died in a duel—he met Burr at Weehawken, New Jersey, on the morning of July 11, 1804. Hamilton was mortally wounded and died the next day.

Selected Primary Writings

The Farmer Refuted (February 23, 1775)13

…I shall, for the present, pass over to that part of your pamphlet, in which you endeavour to establish the supremacy of the British Parliament over America. After a proper [enlightenment] of this point, I shall draw such inferences, as will sap the foundation of every thing you have offered.

The first thing that presents itself is a wish, that “I had, explicitly, declared to the public my ideas of the natural rights of mankind. Man, in a state of nature (you say) may be considered, as perfectly free from all restraints of law and government, and, then, the weak must submit to the strong.”

I shall, henceforth, begin to make some allowance for that enmity, you have discovered to the natural rights of mankind. For, though ignorance of them in this enlightened age cannot be admitted, as a sufficient excuse for you; yet, it ought, in some measure, to extenuate your guilt. If you will follow my advice, there still may be hopes of your reformation. Apply yourself, without delay, to the study of the law of nature. I would recommend to your perusal Grotius, Pufendorf, Locke, Montesquieu, and Burlamaqui.[14] I might mention other excellent writers on this subject; but if you attend, diligently, to these, you will not require any others.

There is so strong a similitude between your political principles and those maintained by Mr. [Thomas] Hobbes, that, in judging from them, a person might very easily mistake you for a disciple of his. His opinion was, exactly, coincident with yours, relative to man in a state of nature. He held, as you do, that he was, then, perfectly free from all restraint of law and government. Moral obligation, according to him, is derived from the introduction of civil society; and there is no virtue, but what is purely artificial, the mere contrivance of politicians, for the maintenance of social intercourse. But the reason he run [sic] into this absurd and impious doctrine, was, that he disbelieved the existence of an intelligent superintending principle, who is the governor, and will be the final judge of the universe.

As you, sometimes, swear by him that made you, I conclude, your sentiment does not correspond with his, in that which is the basis of the doctrine, you both agree in; and this makes it impossible to imagine whence this congruity between you arises. To grant, that there is a supreme intelligence, who rules the world, and has established laws to regulate the actions of his creatures, and, still, to assert, that man, in a state of nature, may be considered as perfectly free from all restraints of laws and government, appear to a common understanding, altogether irreconcilable.

Good and wise men, in all ages, have embraced a very dissimilar theory. They have supposed, that the deity, from the relations, we stand in, to himself and to each other, has constituted an eternal and immutable law, which is, indispensably, obligatory upon all mankind, prior to any human institution whatever.

This is what is called the law of nature, “which, being coeval with mankind, and dictated by God himself, is, of course, superior in obligation to any other. It is binding over all the globe, in all countries, and at all times. No human laws are of any validity, if contrary to this; and such of them as are valid, derive all their authority, mediately or immediately, from this original.” BLACKSTONE.[15]

Upon this law, depend the natural rights of mankind, the supreme being gave existence to man, together with the means of preserving and beatifying that existence. He endowed him with rational faculties, by the help of which, to discern and pursue such things, as were consistent with his duty and interest, and invested him with an inviolable right to personal liberty, and personal safety.

Hence, in a state of nature, no man had any moral power to deprive another of his life, limbs, property or liberty; nor the least authority to command, or exact obedience from him; except that which arose from the ties of consanguinity.

Hence also, the origin of all civil government, justly established, must be a voluntary compact, between the rulers and the ruled; and must be liable to such limitations, as are necessary for the security of the absolute rights of the latter; for what original title can any man or set of men have, to govern others, except their own consent? To usurp dominion over a people, in their own despite, or to grasp at a more extensive power than they are willing to entrust, is to violate that law of nature, which gives every man a right to his personal liberty; and can, therefore, confer no obligation to obedience.

“The principal aim of society is to protect individuals, in the enjoyment of those absolute rights, which were vested in them by the immutable laws of nature; but which could not be preserved, in peace, without that mutual assistance, and intercourse, which is gained by the institution of friendly and social communities. Hence it follows, that the first and primary end of human laws, is to maintain and regulate these absolute rights of individuals.” BLACKSTONE.[16]

If we examine the pretensions of Parliament, by this criterion, which is evidently a good one, we shall presently detect their injustice. First, they are subversive of our natural liberty, because an authority is assumed over us, which we by no means assent to. And secondly, they divest us of that moral security, for our lives and properties, which we are entitled to, and which it is the primary end of society to bestow. For such security can never exist, while we have no part in making the laws that are to bind us and while it may be the interest of our uncontrolled legislators to oppress us as much as possible.

To deny these principles will be not less absurd, than to deny the plainest axioms: I shall not, therefore, attempt any further illustration of them….

…I have taken a pretty general survey of the American Charters, and proved to the satisfaction of every unbiassed person, that they are entirely discordant with that sovereignty of parliament, for which you are an advocate. The disingenuity of your extracts (to give it no harsher name) merits the severest censure, and will no doubt serve to discredit all your former, as well as future, labors in your favourite cause of despotism….

Boston was the first victim to the meditated vengeance. An act was passed to block up her ports and destroy her commerce with every aggravating circumstance that can be imagined. It was not left at her option to elude the stroke by paying for the tea, but she was also to make such satisfaction to the officers of his majesty’s revenue and others who might have suffered as should be judged reasonable by the governor. Nor is this all, before her commerce could be restored, she must have submitted to the authority claimed and exercised by the parliament.

Had the rest of America passively looked on, while a sister colony was subjugated, the same fate would gradually have overtaken all. The safety of the whole depends upon the mutual protection of every part. If the sword of oppression be permitted to lop off one limb without opposition, reiterated strokes will soon dismember the whole body. Hence it was the duty and interest of all the colonies to succour and support the one which was suffering. It is sometimes sagaciously urged, that we ought to commisserate the distresses of the people of Massachusetts, but not intermeddle in their affairs, so far as perhaps to bring ourselves into like circumstances with them. This might be good reasoning, if our neutrality would not be more dangerous, than our participation. But I am unable to conceive how the colonies in general would have any security against oppression if they were once to content themselves with barely pitying each other, while parliament was prosecuting and enforcing its demands. Unless they continually protect and assist each other, they must all inevitably fall a prey to their enemies.

Extraordinary emergencies require extraordinary expedients. The best mode of opposition was that in which there might be an union of councils. This was necessary to ascertain the boundaries of our rights; and to give weight and dignity to our measures, both in Britain and America. A Congress was accordingly proposed, and universally agreed to.

You, Sir, triumph in the supposed illegality of this body; but, granting your supposition were true, it would be a matter of no real importance. When the first principles of civil society are violated, and the rights of a whole people are invaded, the common forms of municipal law are not to be regarded. Men may then betake themselves to the law of nature; and, if they but conform to their actions, to that standard, all cavils against them, betray either ignorance or dishonesty. There are some events in society, to which human laws cannot extend; but when applied to them lose all their force and efficacy. In short, when human laws contradict or discountenance the means…necessary to preserve the essential rights of any society, they defeat the proper end of all laws, and so become null and void.…

First Report on Public Credit (January 9, 1790)17

…While the observance of that good faith, which is the basis of public credit, is recommended by the strongest inducements of political expediency, it is enforced by considerations of still greater authority. There are arguments for it, which rest on the immutable principles of moral obligation. And in proportion as the mind is disposed to contemplate, in the order of Providence, an intimate connection between public virtue and public happiness, will be its repugnancy to a violation of those principles.

This reflection derives additional strength from the nature of the debt of the United States. It was the price of liberty. The faith of America has been repeatedly pledged for it, and with solemnities, that give peculiar force to the obligation. There is indeed reason to regret that it has not hitherto been kept; that the necessities of the war, conspiring with inexperience in the subjects of finance, produced direct infractions; and that the subsequent period has been a continued scene of negative violation, or non-compliance. But a diminution of this regret arises from the reflection, that the last seven years have exhibited an earnest and uniform effort, on the part of the government of the union, to retrieve the national credit, by doing justice to the creditors of the nation; and that the embarrassments of a defective constitution, which defeated this laudable effort, have ceased….

It cannot but merit particular attention, that among ourselves the most enlightened friends of good government are those, whose expectations are the highest.

To justify and preserve their confidence; to promote the encreasing respectability of the American name; to answer the calls of justice; to restore landed property to its due value; to furnish new resources both to agriculture and commerce; to cement more closely the union of the states; to add to their security against foreign attack; to establish public order on the basis of an upright and liberal policy. These are the great and invaluable ends to be secured, by a proper and adequate provision, at the present period, for the support of public credit.

To this provision we are invited, not only by the general considerations, which have been noticed, but by others of a more particular nature. It will procure to every class of the community some important advantages, and remove some no less important disadvantages.

The advantage to the public creditors from the increased value of that part of their property which constitutes the public debt, needs no explanation.

But there is a consequence of this, less obvious, though not less true, in which every other citizen is interested. It is a well known fact, that in countries in which the national debt is properly funded, and an object of established confidence, it answers most of the purposes of money. Transfers of stock or public debt are there equivalent to payments in specie; or in other words, stock, in the principal transactions of business, passes current as specie. The same thing would, in all probability happen here, under the like circumstances.

The benefits of this are various and obvious.

First. Trade is extended by it; because there is a larger capital to carry it on, and the merchant can at the same time, afford to trade for smaller profits; as his stock, which, when unemployed, brings him in an interest from the government, serves him also as money, when he has a call for it in his commercial operations.

Secondly. Agriculture and manufactures are also promoted by it: For the like reason, that more capital can be commanded to be employed in both; and because the merchant, whose enterprize in foreign trade, gives to them activity and extension, has greater means for enterprize.

Thirdly. The interest of money will be lowered by it; for this is always in a ratio, to the quantity of money, and to the quickness of circulation. This circumstance will enable both the public and individuals to borrow on easier and cheaper terms….

It is agreed on all hands, that that part of the debt which has been contracted abroad, and is denominated the foreign debt, ought to be provided for, according to the precise terms of the contracts relating to it. The discussions, which can arise, therefore, will have reference essentially to the domestic part of it, or to that which has been contracted at home. It is to be regretted, that there is not the same unanimity of sentiment on this part, as on the other.

The Secretary has too much deference for the opinions of every part of the community, not to have observed one, which has, more than once, made its appearance in the public prints, and which is occasionally to be met with in conversation. It involves this question, whether a discrimination ought not to be made between original holders of the public securities, and present possessors, by purchase. Those who advocate a discrimination are for making a full provision for the securities of the former, at their nominal value; but contend, that the latter ought to receive no more than the cost to them, and the interest: And the idea is sometimes suggested of making good the difference to the primitive possessor….

The impolicy of a discrimination results from two considerations; one, that it proceeds upon a principle destructive of that quality of the public debt, or the stock of the nation, which is essential to its capacity for answering the purposes of money—that is the security of transfer; the other, that as well on this account, as because it includes a breach of faith, it renders property in the funds less valuable; consequently induces lenders to demand a higher premium for what they lend, and produces every other inconvenience of a bad state of public credit.

It will be perceived at first sight, that the transferable quality of stock is essential to its operation as money, and that this depends on the idea of complete security to the transferree, and a firm persuasion, that no distinction can in any circumstances be made between him and the original proprietor….

The Secretary concluding, that a discrimination, between the different classes of creditors of the United States, cannot with propriety be made, proceeds to examine whether a difference ought to be permitted to remain between them, and another description of public creditors—Those of the states individually.

The Secretary, after mature reflection on this point, entertains a full conviction, that an assumption of the debts of the particular states by the union, and a like provision for them, as for those of the union, will be a measure of sound policy and substantial justice.

It would, in the opinion of the Secretary, contribute, in an eminent degree, to an orderly, stable and satisfactory arrangement of the national finances….

The principal question then must be, whether such a provision cannot be more conveniently and effectually made, by one general plan issuing from one authority, than by different plans originating in different authorities….

Persuaded as the Secretary is, that the proper funding of the present debt, will render it a national blessing: Yet he is so far from acceding to the position, in the latitude in which it is sometimes laid down, that “public debts are public benefits,” a position inviting to prodigality, and liable to dangerous abuse,—that he ardently wishes to see it incorporated, as a fundamental maxim, in the system of public credit of the United States, that the creation of debt should always be accompanied with the means of extinguishment. This he regards as the true secret for rendering public credit immortal. And he presumes, that it is difficult to conceive a situation, in which there may not be an adherence to the maxim. At least he feels an unfeigned solicitude, that this may be attempted by the United States, and that they may commence their measures for the establishment of credit, with the observance of it….

Letters from Tully

Tully No. I (August 23, 1794)18

It has from the first establishment of your present constitution been predicted, that every occasion of serious embarrassment which should occur in the affairs of the government—every misfortune which it should experience, whether produced from its own faults or mistakes, or from other causes, would be the signal of an attempt to overthrow it, or to lay the foundation of its overthrow, by defeating the exercise of constitutional and necessary authorities. The disturbances which have recently broken out in the western counties of Pennsylvania furnish an occasion of this sort. It remains to see whether the prediction which has been quoted, proceeded from an unfounded jealousy excited by partial differences of opinion, or was a just inference from causes inherent in the structure of our political institutions….

Tully No. II (August 26, 1794)19

…The Constitution you have ordained for yourselves and your posterity contains this express clause, “The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and Excises, to pay the debts, and provide for the common defence and general welfare of the United States.” You have then, by a solemn and deliberate act, the most important and sacred that a nation can perform, pronounced and decreed, that your Representatives in Congress shall have power to lay Excises. You have done nothing since to reverse or impair that decree….

But the four western counties of Pennsylvania, undertake to rejudge and reverse your decrees[. Y]ou have said, “The Congress shall have power to lay Excises.” They say, “The Congress shall not have this power.” Or what is equivalent—they shall not exercise it:—for a power that may not be exercised is a nullity. Your Representatives have said, and four times repeated it, “an excise on distilled spirits shall be collected.” They say it shall not be collected. We will punish, expel, and banish the officers who shall attempt the collection. We will do the same by every other person who shall dare to comply with your decree expressed in the Constitutional character; and with that of your Representative expressed in the Laws. The sovereignty shall not reside with you, but with us. If you presume to dispute the point by force—we are ready to measure swords with you….

If there is a man among us who shall…inculcate directly, or indirectly, that force ought not to be employed to compel the Insurgents to a submission to the laws, if the pending experiment to bring them to reason (an experiment which will immortalize the moderation of the government) shall fail; such a man is not a good Citizen; such a man however he may prate and babble republicanism, is not a republican; he attempts to set up the will of a part against the will of the whole, the will of a faction, against the will of nation, the pleasure of a few against your pleasure; the violence of a lawless combination against the sacred authority of laws pronounced under your indisputable commission.

Mark such a man, if such there be. The occasion may enable you to discriminate the true from pretended Republicans; your friends from the friends of faction. ’Tis in vain that the latter shall attempt to conceal their pernicious principles under a crowd of odious invectives against the laws. Your answer is this: “We have already in the Constitutional act decided the point against you, and against those for whom you apologize. We have pronounced that excises may be laid and consequently that they are not as you say inconsistent with Liberty. Let our will be first obeyed and then we shall be ready to consider the reason which can be afforded to prove our judgement has been erroneous…. We have not neglected the means of amending in a regular course the Constitutional act…. In a full respect for the laws we discern the reality of our power and the means of providing for our welfare as occasion may require; in the contempt of the laws we see the annihilation of our power; the possibility, and the danger of its being usurped by others & of the despotism of individuals succeeding to the regular authority of the nation.”

That a fate like this may never await you, let it be deeply imprinted in your minds and handed down to your latest posterity, that there is no road to despotism more sure or more to be dreaded than that which begins at anarchy.

Tully No. III (August 28, 1794)20

If it were to be asked, What is the most sacred duty and the greatest source of security in a Republic? the answer would be, An inviolable respect for the Constitution and Laws—the first growing out of the last. It is by this, in a great degree, that the rich and powerful are to be restrained from enterprises against the common liberty— operated upon by the influence of a general sentiment, by their interest in the principle, and by the obstacles which the habit it produces erects against innovation and encroachment. It is by this, in a still greater degree, that caballers, intriguers, and demagogues are prevented from climbing on the shoulders of faction to the tempting seats of usurpation and tyranny….

Government is frequently and aptly classed under two descriptions, a government of FORCE and a government of LAWS; the first is the definition of despotism—the last, of liberty. But how can a government of laws exist where the laws are disrespected and disobeyed? Government supposes controul. It is the POWER by which individuals in society are kept from doing injury to each other and are bro’t to co-operate to a common end. The instruments by which it must act are either the AUTHORITY of the Laws or FORCE. If the first be destroyed, the last must be substituted; and where this becomes the ordinary instrument of government there is an end to liberty.

Those, therefore, who preach doctrines, or set examples, which undermine or subvert the authority of the laws, lead us from freedom to slavery; they incapacitate us for a GOVERNMENT OF LAWS, and consequently prepare the way for one of FORCE, for mankind MUST HAVE GOVERNMENT OF ONE SORT OR ANOTHER.

There are indeed great and urgent cases where the bounds of the constitution are manifestly transgressed, or its constitutional authorities so exercised as to produce unequivocal oppression on the community, and to render resistance justifiable. But such cases can give no color to the resistance by a comparatively inconsiderable part of a community, of constitutional laws distinguished by no extraordinary features of rigour or oppression, and acquiesced in by the BODY OF THE COMMUNITY.

Such a resistance is treason against society, against liberty, against everything that ought to be dear to a free, enlightened, and prudent people. To tolerate were to abandon your most precious interests. Not to subdue it, were to tolerate it….

Tully No. IV (September 2, 1794)21

…Fellow Citizens—You are told, that it will be intemperate to urge the execution of the laws which are resisted—what? will it be indeed intemperate in your Chief Magistrate, sworn to maintain the Constitution, charged faithfully to execute the Laws, and authorized to employ for that purpose force when the ordinary means fail—will it be intemperate in him to exert that force, when the constitution and the laws are opposed by force? Can he answer it to his conscience, to you not to exert it?

Yes, it is said; because the execution of it will produce civil war, the consummation of human evil.

Fellow-Citizens—Civil War is undoubtedly a great evil. It is one that every good man would wish to avoid, and will deplore if inevitable. But it is incomparably a less evil than the destruction of Government. The first brings with it serious but temporary and partial ills—the last undermines the foundations of our security and happiness—where should we be if it were once to grow into a maxim, that force is not to be used against the seditious combinations of parts of the community to resist the laws?... The Hydra Anarchy would rear its head in every quarter. The goodly fabric you have established would be rent assunder, and precipitated into the dust…. You know that the POWER of the majority and LIBERTY are inseparable—destroy that, and this perishes….

Recommended Readings

- Forrest McDonald, Alexander Hamilton: A Biography (New York: W.W. Norton, 1982).

- Richard Brookhiser, Alexander Hamilton, American (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1999).

- Gerald Stourzh, Alexander Hamilton and the Idea of Republican Government (Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press, 1970).

- Karl-Friedrich Walling, Republican Empire: Alexander Hamilton on War and Free Government (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1999).

- Stephen F. Knott, Alexander Hamilton and the Persistence of Myth (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2002).

- Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton (New York: Penguin Books, 2005).

Notes

[1] Daniel Webster, speech at a public dinner in his honor in New York, March 10, 1831, in The Works of Daniel Webster, 18th ed. (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1881), p. 200, https://dn790009.ca.archive.org/0/items/worksofdanielwebv1webs/worksofdanielwebv1webs.pdf (accessed April 28, 2025)

[2] Alexander Hamilton, “New York Ratifying Convention. Remarks (Francis Childs’s Version), [24 June 1788],” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-05-02-0012-0023 (accessed March 27, 2025).

[3] See Alexander Hamilton, “A Letter from Phocion to the Considerate Citizens of New York, [1–27 January 1784],” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-03-02-0314 (accessed March 27, 2025), and “Second Letter from Phocion, [April 1784],” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-03-02-0347 (accessed March 27, 2025).

[4] “From Alexander Hamilton to John Jay, 26 November 1775,” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-01-02-0060 (accessed March 27, 2025).

[5] Alexander Hamilton, “The Examination Number VIII, [12 January 1802],” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-25-02-0282 (accessed March 27, 2025).

[6] Alexander Hamilton, “Report Relative to a Provision for the Support of Public Credit, [9 January 1790],” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-06-02-0076-0002-0001 (accessed February 7, 2025).

[7] Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 72, March 19, 1788, National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-04-02-0223 (accessed April 28, 2025). Emphasis added.

[8] “Alexander Hamilton’s Final Version of the Report on the Subject of Manufactures, [5 December 1791],” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-10-02-0001-0007 (accessed March 27, 2025).

[9] Ibid.

[10] Hamilton, Federalist No. 72.

[11] Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 23, December 18, 1787, National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-04-02-0180 (accessed April 28, 2025). Emphasis in original.

[12] “From Alexander Hamilton to ———, 26 September 1792,” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-12-02-0334 (accessed March 27, 2025).

[13] Alexander Hamilton, “The Farmer Refuted, &c., [23 February] 1775,” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-01-02-0057#ARHN-01-01-02-0057-fn-0002 (accessed April 27, 2025). Emphasis in original. Written as a reply to Samuel Seabury’s View of the Controversy Between Great-Britain and her Colonies, which Seabury had written in response to Hamilton’s Full Vindication of the Members of Congress.

[14] “Political philosophers Hugo Grotius (1583–1645); Samuel von Pufendorf (1632–1694); John Locke (1632–1704); Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (1689–1755); and Jean-Jacques Burlamaqui (1694–1748).” Alexander Hamilton, “The Farmer Refuted,” ed. & intro. Robert McDonald, Ashbrook Center at Ashland University, Teaching American History, note 2, https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/the-farmer-refuted-2/ (accessed March 27, 2025).

[15] Quoting William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England (Philadelphia: Robert Bell, 1771–1772), Vol. 1, p. 41.

[16] Quoting ibid., p. 124.

[17] Alexander Hamilton, “Report Relative to a Provision for the Support of Public Credit, [9 January 1790],” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-06-02-0076-0002-0001 (accessed April 28, 2025). Emphasis in original.

[18] Alexander Hamilton, “Tully No. I, [23 August 1794]” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-17-02-0102 (accessed April 27, 2025). Written for the American Daily Advertiser.

[19] Alexander Hamilton, “Tully No. II, [26 August 1794],” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-17-02-0116 (accessed April 27, 2025). Emphasis in original. Written for the American Daily Advertiser.

[20] Alexander Hamilton, “Tully No. III, [28 August 1794],” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-17-02-0130 (accessed April 27, 2025). Emphasis in original. Written for the American Daily Advertiser.

[21] Alexander Hamilton, “Tully No. IV, [2 September 1794],” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-17-02-0145 (accessed April 27, 2025). Emphasis in original. Written for the American Daily Advertiser.