Hundreds of thousands of Floridians owe their jobs to international trade and investment. The benefits of international commerce are reflected in the voting record of the state’s congressional delegation, which overwhelmingly supported free trade agreements (FTAs) with Colombia, Panama, and South Korea in 2011.

However, the state’s elected representatives have not always supported trade policies that would benefit most people in the state. In 2013, most of Florida’s Representatives and both Florida Senators voted against reforming the U.S. sugar program, which would have dramatically reduced the cost of sugar.

Florida’s congressional delegation can best represent Floridians by continuing to support agreements that reduce trade barriers. Florida’s elected representatives should also oppose U.S. policies that protect special interests from competition while driving up prices for everyone else. Giving people in Florida the freedom to buy sugar produced in other countries and reforming maritime laws that hinder job-creating waterborne commerce would be a good start.

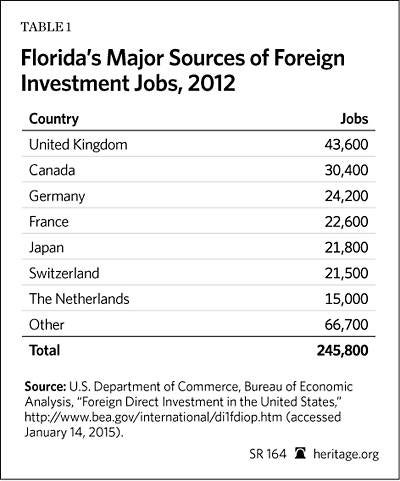

Foreign Investment Supports Florida Jobs

Some critics of free trade argue that U.S. workers cannot compete with low-wage workers in other countries, but the facts show otherwise. The United States is a magnet for job-creating foreign investment. For example, in October 2014, Brazilian aircraft manufacturer Embraer announced plans to add 600 new aircraft production jobs in Melbourne, Florida. Over 245,000 people in Florida work for U.S. affiliates of foreign companies ranging from Airbus to Zurich Insurance Group.[1] That is more than the entire population of Tallahassee.[2]

Enterprise Florida reported:

Attracted by its large and booming economy, stable business environment, and international workforce, new business investments from around the world pour into Florida every year, making it one of the top U.S. destinations for foreign direct investment (FDI).[3]

Imports Create Jobs and Benefit Consumers

More than 1.8 million Floridians are employed in the wholesale, retail, and transportation industries, moving and selling goods made in the United States and around the world.[4]

Millions of Americans benefit from fresh fruit, vegetables, fish, flowers, and other goods from South America that arrive via Miami International Airport. Every day, 32,000 boxes of flowers from Colombia and other South American countries arrive at Miami’s airport for delivery across the United States.[5] More than 6,000 people work for flower importers, bouquet companies, brokers, and related companies in Florida.[6] Americans are happier and healthier as a result of these imports.

To paraphrase James Glassman, visiting fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, free trade fights cancer by making fresh fruits and vegetables more affordable.[7] Many Americans can thank imports arriving via Miami for the fresh fruit and vegetables at their local supermarkets. Miami’s proximity to the Caribbean and South America makes it a leading destination for avocadoes from Chile, melons from Costa Rica, mangoes from Ecuador, pineapples from Guatemala and Honduras, and grapes from Peru. From Miami, produce is shipped across the United States, providing residents of Chicago and New York with fresh fruits and vegetables in the middle of winter within days of the produce reaching the United States.[8]

Over half of U.S. imports are intermediate goods used by U.S. manufacturers. According to a study by the Peterson Institute for International Economics, the use of imported inputs from 1961 to 2000 added $1.1 trillion to the U.S. economy, equivalent to $9,400 per household.[9]

Exports Boost Florida’s Economy

According to the U.S. International Trade Administration, 275,221 Florida jobs are supported by exports.[10] Exports of goods from Florida are up 10.7 percent since 2010, from $55.4 billion to $61.3 billion.[11]

Many sectors of Florida’s economy benefit from exports. Exports account for 18.3 percent of Florida’s manufacturing jobs.[12] In 2012, Florida exported $3.6 billion in agricultural products, equivalent to nearly 40 percent of the state’s total agricultural output.[13] Florida’s service industries, including the travel and professional service sectors, account for another $33 billion in exports.[14]

U.S. free trade agreements have expanded Florida’s export opportunities. About one-third of Florida exports go to countries that have trade agreements with the United States. Exports to Canada and Mexico are up 173 percent since the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) took effect in 1994. Likewise, Florida’s exports to Chile have increased by 320 percent since the U.S.–Chile Free Trade Agreement was implemented in 2004.[15]

International Trade Is Not Responsible for Job Losses

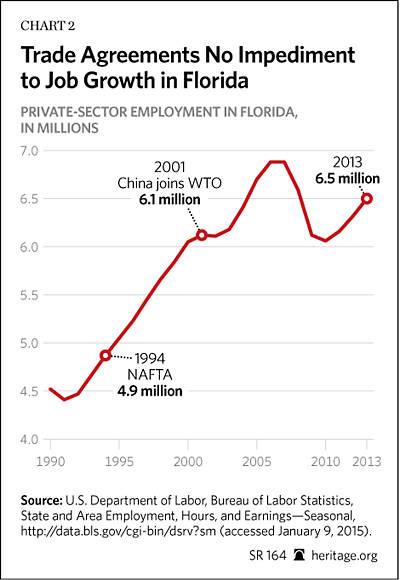

Critics claim that trade agreements have reduced the number of jobs in Florida. According to the Economic Policy Institute (EPI), trade with China cost Florida 106,100 net jobs from 2001 to 2011.[16] The EPI further claims that NAFTA cost Florida 28,800 net jobs as of 2010.[17]

Both of those claims are inaccurate. Economic opportunities created by trade and technology create new jobs in some industries while reducing employment in others, but there has been no net loss of jobs in Florida due to trade with people in Mexico, China, or anyplace else. From 2001 to 2013, total Florida private-sector employment increased by 390,000 jobs. Since NAFTA took effect in 1994, the state added over 1.6 million net new private-sector jobs.[18]

Public Citizen claims that Florida has lost 125,440 manufacturing jobs since NAFTA took effect in 1994.[19] That does not mean NAFTA is responsible for those job losses. In fact, Florida’s manufacturing output is significantly higher now than in 1994, even after adjusting for inflation. Florida’s real manufacturing gross domestic product (GDP) has increased by more than 21 percent since 2000.[20]

A Maritime Link to Foreign Markets

According to the Florida Ports Council, activity at the state’s 15 ports supports more than 680,000 direct and indirect jobs.[21] Of these, 37,771 port-related jobs are directly created by imports and exports of cargo.[22]

The number of jobs supported by Florida’s ports will likely grow even more due to increases in trade volume and shipping capacities. The Panama Canal is expanding to handle larger vessels that can transport more than twice as much cargo as their predecessors.[23] The ports of Miami, Tampa Bay, and Jacksonville are modernizing to accommodate these large new ships, generating even more trade-related employment.

As the director of the PortMiami observed, “The bigger the ships, the more cargo, the more jobs.”[24] Deepening the channel at the PortMiami to make it the “port of first call” for ships arriving via the Panama Canal could create 30,000 new jobs.[25] Port Tampa Bay estimates that deepening the port’s channel to accommodate larger ships could create 7,000 new jobs.[26] Expansion at Port Manatee is projected to create 180 new jobs.[27]

Another 20,032 port-related jobs are generated by the cruise industry. Miami has long been the “cruise capital of the world,” with more than 4 million people a year passing through its terminals.[28] More than 14 million cruise passengers embarked and disembarked through Florida in 2013, accounting for 60.2 percent of U.S. cruise traffic.[29]

Florida’s Legislators Increasingly Support Free Trade

In the late 20th century, Florida legislators were divided over free trade. Both Florida Senators supported NAFTA in 1993, but Florida’s Representatives voted 13–10 for NAFTA. Similarly, in 2004, both Senators supported China’s entry into the World Trade Organization, but the state’s House delegation split, with 11 voting yes and 10 voting no.

In 2004, Congress barely passed the Dominican Republic–Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA–DR), which expanded free trade among the United States, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and the Dominican Republic. The vote was 55–45 in the Senate, and 217–215 in the House of Representatives.[30] Without support from Florida’s legislators, Congress might have rejected the legislation required to implement CAFTA–DR. Both of Florida’s Senators voted yes, along with 18 Representatives. Just eight of Florida’s Representatives voted against the agreement.

For the most part, Florida’s congressional delegation has supported open trade and investment in recent years, enabling the state’s residents to reap the benefits of global commerce. In 2011, Congress voted on FTAs with Colombia, Panama, and South Korea. Senators Bill Nelson (D–FL) and Marco Rubio (R–FL) voted for all three FTAs, and the combined vote for all three agreements by the state’s Representatives was an overwhelming 62–10. Florida Governor Rick Scott (R) also supported those agreements and criticized President Obama for his delay in submitting them to Congress for a vote.[31]

The Sugar Program Hurts Florida

There is, however, a costly exception to support for free trade by Florida’s congressional delegation: the U.S. sugar program. The federal government artificially inflates sugar prices by imposing quotas that cap the amount that food manufacturers and consumers in the United States can buy from producers in other countries. As of December 2014, Florida bakeries and candy companies paid twice as much as their foreign competitors for refined sugar. From 2000 to 2014, Americans paid an average of 85 percent more for refined sugar than people in other countries.[32] One Florida business explained:

We have manufactured citrus candies, coconut patties, marmalades, and jellies at Davidson of Dundee in Dundee, Florida since 1967. We have had to compete with foreign companies that are able to purchase sugar on the world market for nearly half the price we pay. We employ Americans, make our products in the USA, and yet are at the mercy of the two major sugar “families” that are able to control the US sugar market. It is quite unbelievable. We have seen sugar rise to .70/lb and fall to .30/lb while the world prices are nearly half of those prices. We are hurting ourselves, and affecting jobs and of course, tax revenue for the government on our profits. We are looking for ways to manufacture out-of-country to compete. This is such a con.[33]

Sugar represents just 2 percent of the total value of U.S. crop production, but the industry accounts for 33 percent of crop industries’ total campaign donations and 40 percent of crop industries’ total lobbying expenditures.[34]

Just three of the state’s 27 legislators supported an amendment to reform the sugar program in 2013.[35] Both of Florida’s Senators voted against reform.[36]

Restrictions on Cargo and Cruise Vessels

The Merchant Marine Act of 1920 (the Jones Act) and the Passenger Vessel Services Act of 1886 require that ships transporting goods or people between two points in the United States must be built in the United States, mostly U.S.-owned, and mostly crewed by U.S. citizens. These laws are designed to protect U.S. shipbuilders from competition, but they impose steep costs on Americans who use ships for domestic transportation.

According to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, “The coastwise laws are highly protectionist provisions that are intended to create a ‘coastwise monopoly’ in order to protect and develop the American merchant marine, shipbuilding, etc.”[37]

The Passenger Vessel Services Act limits innovation in the cruise industry. The Florida Department of Transportation described how the law works:

A significant legal restriction impacting potential U.S./Florida cruise itineraries is another federal mandate related to cabotage [shipping between U.S. ports]—the Passenger Vessel Services Act of 1886, which imposes restrictions on foreign-flagged passenger vessels. These vessels are allowed to make round trips to U.S. ports with calls at other U.S. ports as long as at least one foreign port is called. Passengers cannot embark or debark at a port of call, but must embark and debark at the port of origin. Violations of this statute carry a prohibitively significant per-passenger penalty of $300…. This may impact port-of-call opportunities at Florida’s ports.[38]

The Jones Act’s cargo shipping restrictions increase the price of gasoline for Florida drivers. According to Joe Petrowski, chief executive officer of Gulf Oil, “If foreign owned and flag ships were able to carry gasoline in US waters, the price of gasoline in the North East and in Florida could be 20 to 30 cents lower.”[39]

The Jones Act also limits opportunities to transship cargo through Florida’s ports. It makes it illegal for foreign-built vessels to drop off goods in Miami and then pick up goods to be delivered to Jacksonville or any other U.S. port. According to one study, the benefits of allowing transshipment of goods within the United States could exceed $200 million.[40] Florida’s government describes the state as the “gateway to the world.”[41] If companies were allowed to transship cargo through Florida’s ports, the state could more effectively serve as the “gateway to the United States.”

In addition, the Jones Act is hindering Florida’s efforts to modernize its ports because only U.S. companies are allowed to dredge U.S. ports. According to Pieter van Oord, chief executive officer of Dutch marine contractor Van Oord:

[The United States] is twenty years behind us. Because of the protection they have never felt the need to innovate…. The cost per cubic meter of dredging in the United States is therefore twice as expensive as elsewhere in the world, ultimately at the expense of the American citizen.[42]

The 2014 Water Resources Reform and Development Act included $2 billion to expand Florida’s ports, and the 2014 state budget included $139 million for seaport infrastructure improvements.[43] Much of that money will be wasted due to the Jones Act’s ban on dredging by foreign-owned companies.

Florida’s Future Is Bright

Florida is positioned to prosper from continued growth in trade with Latin America and the rest of the world as trade barriers are reduced. Physical barriers, such as limits imposed by canals and ports that cannot handle modern cargo ships, and government barriers, such as limits on shipping and the use of imported inputs, are falling around the globe. Florida’s congressional delegation should take the lead in making sure U.S. government impediments to trade and prosperity fall as well.

—Bryan Riley is Jay Van Andel Senior Analyst in Trade Policy in the Center for Trade and Economics, of the Institute for Economic Freedom and Opportunity, at The Heritage Foundation.