My name is Steven Bucci. I am Director of the Douglas and Sarah Allison Center for Foreign and National Security Policy in The Heritage Foundation’s Davis Institute for National Security and Foreign Policy. The views I express in this testimony are my own, and should not be construed as representing any official position of The Heritage Foundation.

I have spent the majority of my life as a military officer; I retired from the Army as a colonel, having served as a Defense Attaché, a human Intelligence collector working in embassies for Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), and as a Special Forces operator and commander of the 3d Battalion, 5th Special Forces Group, fighting terrorism. I also served as the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Homeland Defense, DOD’s representative to the Interagency for Counter Terrorism domestically.

VWP and the Threat of Terror

The Visa Waiver Program (VWP) is a valuable tool supporting U.S. tourism and trade, public diplomacy, and national security. The VWP allows residents of member countries to visit the U.S. without a visa for up to 90 days in exchange for security-cooperation and information-sharing arrangements and reciprocal travel privileges for U.S. residents.

News of European passport holders joining the Islamic State in Iraq and al Sham (ISIS), however, have created concerns about radicalized Western fighters abusing the VWP to engage in terrorism here in the U.S. These concerns, however, are not a good reason to end the VWP. The VWP promotes security and the ISIS threat only emphasizes the importance of the VWP’s intelligence-sharing requirements and adding appropriate nations to the program.

VWP Basics and Benefits

In order to become a VWP member, a country must:

- Demonstrate a non-immigrant-visa refusal rate (the percentage of visa applicants denied by the State Department for a particular nation) of no more than 3 percent;

- Issue all its residents secure, machine-readable biometric passports; and

- Present no discernable threat to U.S. law enforcement or U.S. national security.

Currently, 38 nations are participating in the VWP.[1] As required by the VWP and certain laws, these nations have also agreed to various stipulations and obligations, including requirements to:

- Share intelligence about known or suspected terrorists with the U.S. (per Homeland Security Presidential Directive 6 (HSPD-6));

- Exchange biographic, biometric, and criminal data with the U.S. (automated, via Preventing and Combating Serious Crime (PCSC) agreements);

- Share information on lost and stolen passports (LASP agreements);

- Increase their own airport security requirements; and

- Provide U.S. citizens with a reciprocal ability to travel to that country without a visa.[2]

These features greatly enhance security by providing U.S. law enforcement and security agencies with more information and intelligence on potential terrorists and other bad actors. The VWP makes it easier for U.S. officials to know whether an individual presents a security threat. The VWP also allows the State Department to focus its consular and visa resources on those countries and individuals about which less is known and are higher risks to U.S. security.

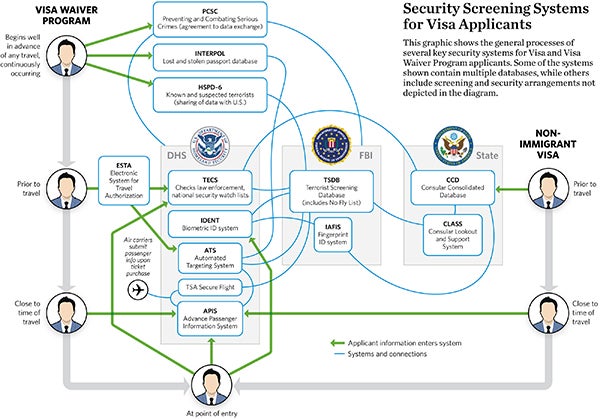

Furthermore, the VWP includes robust screening and security procedures. Every traveler to the U.S. from a VWP country must be pre-screened through the Electronic System for Travel Authorization (ESTA). ESTA data is then checked against multiple databases including Custom and Border Protection’s (CBP) Automating Targeting System (ATS) and TECS system. The ATS is run by the National Targeting Center and checks a variety of databases including the Terrorist Screening Database (TSDB) and Interpol’s data on lost and stolen passports. The ATS gives each individual a risk-based score that determines whether or not the individual should receive additional scrutiny or inspection. TECS queries various databases for information about the person’s eligibility for travel to the U.S. and whether he or she is a known security risk.[3] TECS also checks against the TSDB, which is maintained by the FBI for law enforcement use in apprehending or stopping known or suspected terrorists. [4]

Additionally, when individuals buy their tickets, that information is forwarded from the airlines to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and checked through multiple systems. The Transportation Security Administration’s Secure Flight program collects passenger data and compares it against the TSDB’s No Fly and Selectee lists. CBP’s Advance Passenger Information System (APIS) collects the Passenger Name Record and other information about travelers and forwards the information to the Arrival and Departure Information System (ADIS) to help combat visa overstays, and also to the National Targeting Center and the ATS to detect high-risk travelers.[5]

Upon landing in the U.S., individuals must provide biographic and biometric information that is checked against additional sets of biometric databases controlled by DHS (Automated Biometric Identification System or IDENT) and the FBI (Integrated Automated Fingerprint Identification System or IAFIS). The individual is once again checked through TECS, the ATS, and the APIS and undergoes additional inspection if necessary. At any point in this process, security officials can prevent an individual from entering the U.S. if they are deemed a security risk or ineligible for travel to the U.S. While no system is without flaws, this is a robust screening process. [6]

The main differences between this screening process and the traditional visa screening process are that a traditional visa applicant must have an in-person interview at a U.S. consulate and provide biometric data prior to obtaining a visa. This allows biometric checks to occur prior to travel. The traditional visa process, however, does not have the same information-sharing arrangements that are required to be a part of the VWP that provide the U.S. with data on known and suspected terrorists and serious criminals.

Since the VWP was created in 1986, tourism and related expenditures in the U.S. have dramatically increased. From 2000 to 2013, the number of visitors to the U.S. increased by 18.6 million, a 36 percent increase, to a record number of 69.8 million, with approximately 40 percent of all visitors entering the U.S. through the VWP.[7] As a result, the VWP has helped the U.S. maintain a trade surplus in tourism since 1989, with visitors spending $180.7 billion in 2013, supporting the travel and tourism industries that constitute 2.8 percent of U.S. gross domestic product, including 8 million jobs, as well as many other sectors of the U.S. economy, such as restaurant and consumer-good businesses.[8]

The VWP is also an important tool of foreign policy and public diplomacy. Allowing individuals to visit the U.S. and enjoy our country can improve the foreign public’s understanding and appreciation for America and our culture. By extending the privilege of the VWP to other nations, we deepen diplomatic ties with friendly governments and allies, as well. A graphic depiction of these processes is attached to this submission, showing a side-by-side comparison of the interaction of a VWP traveler and a non-VWP traditional traveler with the various parts of the U.S. systems.

Improvement and Expansion

While the VWP boosts security, diplomacy, trade, and tourism, there are areas for improvement, including information-sharing arrangements and metrics for visa overstays.

As mentioned, VWP participants must enter into various information-sharing arrangements with the U.S., as mandated by the 9/11 Commission Act of 2007. In 2012, the U.S. Government Accountability Office’s (GAO’s) Acting Director of Homeland Security and Justice Rebecca Gambler testified that many nations had not finalized these agreements or begun sharing information. According to GAO data as of January 2011, only 19 of the 36 VWP nations had agreed to share terrorist-watch-list information and only 13 were actually sharing information. Worse yet, only 18 of 36 nations had agreed to share PCSC crime information, and no information-sharing arrangements were fully automated as required.[9]

Since then, however, action on information sharing has dramatically improved: The Congressional Research Service reported that nearly all VWP members had agreed to share information as of February 2014,[10] and, according to a DHS legislative affairs official, as of September 2014 all nations are now sharing information on terrorists, serious criminals, and lost or stolen passports. DHS is, however, still working to automate PCSC data sharing for all VWP participants.[11] Congress should ensure that progress on these agreements continues.

Given the many benefits of the VWP, the U.S. should also examine how to increase VWP membership judiciously. The requirement for a biometric visa-exit system, which is not a cost-effective tool for stopping terrorism or illegal immigration, currently stands in the way of most nations joining the VWP.[12] DHS should be allowed to waive the 3 percent limit on non-immigrant visa-refusal rates, and Congress should add a requirement for low visa-overstay rates instead. The visa-refusal metric is susceptible to subjective decisions by different visa consular officers in different countries that can affect the number of visas refused and granted. A better metric would be to use countries’ visa-overstay rates as a measure of how a country’s citizens respect the terms of their entry into, and time in, the U.S. While such reform would be ideal and more permanent, Congress could also seek to return waiver authority to the DHS Secretary on a short-term basis, allowing the Secretary to accept treaty allies such as Poland into the VWP, so long as their visa-refusal rate was less than 10 percent. Such action would help the U.S. economically, improve security and screening of individuals coming to the U.S., and would remind our allies, especially those like Poland that face an increasingly aggressive Russia, that the U.S. stands by them.

Additional measures, to strengthen the ESTA application or to provide DHS with reasonable tools to ensure member countries are abiding by their agreements, could also be worthwhile reforms. Countries that do not meet the terms of the VWP should face consequences, but full expulsion from the program should not be used lightly.

Conclusion

With many benefits, the VWP is more valuable than ever. The threat of ISIS and radicalized Westerners is real and the U.S. should be using all the intelligence tools at its disposal to find and stop these terrorists. The VWP is one of those tools, and to stop it now would make the U.S. less secure, less prosperous, and less engaged with friends and allies. Instead, we should be looking to improve and expand the program.

Endnotes

[1] U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs, “U.S. Visas: Visa Waiver Program,” http://travel.state.gov/content/visas/english/visit/visa-waiver-program.html (accessed March 12, 2015).

[2] Alison Siskin, “Visa Waiver Program,” Congressional Research Service Report for Congress, February 12, 2014, http://fas.org/sgp/crs/homesec/RL32221.pdf (accessed March 12, 2015).

[3] Lisa Seghetti, “Border Security: Immigration Inspections at Ports of Entry,” Congressional Research Service Report for Congress, January 26, 2015, pp. 9–10, http://fas.org/sgp/crs/homesec/R43356.pdf (accessed March 12, 2015).

[4] Timothy J. Healy, “Statement Before the House Judiciary Committee,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, March 24, 2010, http://www.fbi.gov/news/testimony/sharing-and-analyzing-information-to-prevent-terrorism (accessed March 12, 2015).

[5] Seghetti, “Border Security: Immigration Inspections at Ports of Entry.”

[6] Ibid., pp. 10–11.

[7] Siskin, “Visa Waiver Program,” and U.S. Department of Commerce, Office of Travel and Tourism Industries, “International Arrivals to U.S. by Region and Country of Residency: Historical Visitation 2000–2006,” http://travel.trade.gov/outreachpages/download_data_table/Historical_arrivals_2000_2006.pdf (accessed March 12, 2015).

[8] International Trade Administration, National Travel and Tourism Office, “Fast Facts: United States Travel and Tourism Industry 2013,” http://travel.trade.gov/outreachpages/download_data_table/Fast_Facts_2013.pdf (accessed March, 2015).

[9] Rebecca Gambler, “Visa Waiver Program: Additional Actions Needed to Mitigate Risks and Strengthen Overstay Enforcement,” Government Accountability Office, GAO–12–599T, March 27, 2012, http://www.gao.gov/assets/590/589621.pdf (accessed March 12, 2015), and Jessica Zuckerman, “The Visa Waiver Program: Time for Nations to Bear the Consequences of Non-Compliance,” Heritage Foundation Issue Brief No. 3565, April 12, 2012, http://www.heritage.org/research/reports/2012/04/visa-waiver-program-consequences-of-non-compliance.

[10] Siskin, “Visa Waiver Program.”

[11] Gambler, “Visa Waiver Program,” and phone conversation between David Inserra and DHS official, DHS Office of Legislative Affairs, September 10, 2014.

[12] Steven P. Bucci and David Inserra, “Biometric Exit Improvement Act: Wrong Solution to Broken Visa and Immigration System,” Heritage Foundation Issue Brief No. 4064, October 8, 2013, http://www.heritage.org/research/reports/2013/10/biometric-exit-improvement-act-and-the-broken-visa-and-immigration-system, and Jessica Zuckerman, “Taiwan Admitted to the Visa Waiver Program,” Heritage Foundation Issue Brief No. 3747, October 3, 2012, http://www.heritage.org/research/reports/2012/10/taiwan-admitted-to-the-visa-waiver-program.