Social Security touches the life of almost every worker in America, yet few know how the program works. In practice, Social Security uses complex benefit formulas and detailed rules that make it difficult for people to understand the program’s scope, its financing, how benefits are determined, and a number of other issues. This Backgrounder[1] explains what Social Security is and how it works, in five sections. Unless otherwise noted, all data contained in this paper come from the Social Security Administration.

The individual sections are:

- What Is Social Security? Major Programs and How to Qualify

- Social Security’s Finances

- The Social Security Trust Funds

- Determining Social Security Benefits

- Special Provisions

1. What Is Social Security? Major Programs and How to Qualify

Social Security is a federal income-security program that was established in 1935 as part of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal. As a “pay as you go” program, the payroll taxes paid by current workers are used to fund the benefits of current Social Security recipients. Although originally a program providing economic security to certain retirees, today’s Social Security has expanded to provide a certain level of retirement income to almost all workers, certain family members, and survivors, as well as disability benefits. Overall, about 55 million people receive some type of benefit from Social Security.

Social Security’s Major Programs. Social Security consists of three programs that are administered by the Social Security Administration.

- Retirement. Social Security’s retirement program provides a lifetime monthly income for qualified workers once they reach their full retirement age. Depending on when they were born, that age ranges from 65 to 67. The amount of retirement benefits that a worker receives depends on his or her income while working. Workers also have the option of receiving a lower monthly income starting at age 62.

- Survivors. Social Security’s survivors program provides a monthly lifetime income to the surviving spouse of a deceased worker once he or she reaches retirement age. The amount of the monthly benefit depends on both spouses’ income while they were working. The survivors program also pays benefits to children under the age of 18 and the surviving spouse caring for them. Unless they are disabled, children’s benefits end when the last child either reaches age 18 or graduates from high school, whichever is later.

- Disability. Social Security also pays lifetime monthly income to workers who are disabled and, in some cases, to their spouses and children under the age of 18. These benefits depend on a worker’s earning history.

Qualifying for Social Security. Workers do not automatically qualify for Social Security retirement benefits. They must work and pay a minimum in Social Security taxes for at least 40 quarters (10 years) during their working lives if born in 1929 or later. These 40 quarters need not be consecutive. Currently, workers earn a credit for each three-month period in which they earn at least $1,200. Once they have worked and paid Social Security taxes for the required 40 quarters, they are fully qualified to receive Social Security retirement benefits upon reaching the required age. Some members of the retiree’s family may also receive benefits. Depending on circumstances, those family members could include spouses, current and in some cases divorced; children under the age of 18 or, if they are still in high school, up until age 19; and disabled children of potentially any age.

Workers who have paid Social Security taxes for a certain number of quarters, depending on their age, may qualify for disability benefits; if they pass away, survivors benefits could be paid to their spouses and any children under the age of 18, as well as their dependent parents, in some cases.

Disability benefits are paid to workers who are disabled for at least one year. In order to qualify, a worker must have paid Social Security taxes within a certain past period, depending on age and work history. “Disabled” in this case means unable to perform any substantial gainful work due to severe physical or mental impairment. Determination of eligibility is based on medical evidence and made by a government agency in the state in which the worker lives.

Survivors benefits may also be paid to certain family members of a worker who died before reaching retirement age. To qualify, the worker had to have accumulated a certain number of Social Security credits based on his age at death. Depending on circumstances, eligible family members could include widows or widowers (as well as surviving ex-spouses), children, and dependent parents. In certain cases, there is also a one-time payment of $255 that can be made to the spouse or child of the worker upon his death.

There is no requirement that an individual be an American citizen to qualify for Social Security benefits. While employers are required by other laws to ensure that anyone they hire is either a citizen or a legal immigrant, foreign nationals authorized to work in the U.S. can earn Social Security credits with a valid Social Security number.

Supplemental Security Income. The Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program is not part of Social Security. Even though the Social Security Administration administers SSI, the program is paid for with general tax revenues. No Social Security payroll taxes are used to pay for SSI, which helps aged, blind, and disabled people who have little or no income. It provides cash to meet basic needs for food, clothing, and shelter. To receive SSI, a worker must be blind, disabled, or at least 65 years of age.

Medicare. Medicare is a federal program that helps to pay for older Americans’ health costs. Some people incorrectly consider Medicare to be part of the Social Security system because taxes that finance part of Medicare are lumped together with those that pay for Social Security. However, Medicare is also financed by premiums and general revenue, and it is not administered by the Social Security Administration.

2. Social Security’s Finances

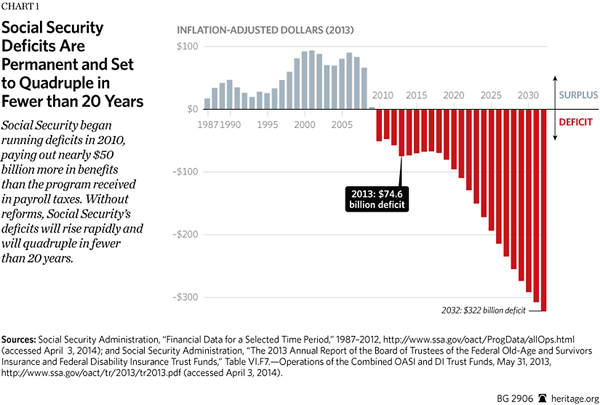

Social Security’s deficits are permanent and growing. In net-present-value terms, Social Security was estimated in 2013 to owe $12.3 trillion more in benefits over its 75-year projection horizon than it will receive in taxes over that period.[2] This number includes $2.7 trillion to repay the special-issue bonds in the trust fund.

Net present value is the amount of money that would have to be invested today in order to have enough money to pay deficits in the future. In other words, Congress would have to invest $12.3 trillion today in order to have enough money to pay all of Social Security’s promised benefits through 2087. This money would be in addition to what Social Security receives during those years from its payroll taxes.

Social Security is the largest federal spending program, surpassing national defense since 1993. In 2012, the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund, which pays for retirement and survivors benefits, took in $731.1 billion, which includes $102.8 billion that came from a paper transaction that credited interest to the trust fund. Excluding the interest, in 2012, the retirement and survivors program had an income of $628.3 billion but paid out $637.9 billion in benefits, leaving a deficit for 2012 of $9.6 billion. Additional deficits were suffered by Social Security’s disability program.

Counting both programs together, in 2012, Social Security spent $55 billion more in benefits than it took in from its payroll tax and income tax. This deficit is in addition to a $45 billion gap in 2011 and in addition to an expected average annual gap of about $100 billion over the next decade. These deficits will quickly balloon to alarming proportions.

The Trust Fund Does Not Make Social Security Healthy. The existence of a trust fund does not make Social Security healthy. Although those assets are guaranteed by the full faith and credit of the United States, the bonds it contains must be repaid using general revenue that would otherwise go to other programs. Similarly, the interest that Social Security receives on existing trust fund balances is not spendable income. It merely inflates the numbers in the trust fund and increases the amount that Social Security will eventually receive from general revenue. The only part that counts today is the cash that Social Security receives from the Treasury to cover its annual operating losses.

Many opponents of reform claim that raising payroll taxes by about 2.7 percent (the average percentage difference between revenues and outlays over the 75-year period) would permanently solve Social Security’s problems. The reality is that the program’s future deficits are projected to be both large and growing, so this tax increase would still leave a huge shortfall. Modest changes will not fix the current system.

The Taxes that Pay for Social Security. Unlike most other government programs, Social Security (like Medicare) is funded through explicit taxes that are not supposed to be used for any other purpose. These taxes are based on a worker’s earned income and deducted from his or her paychecks. For that reason, Social Security taxes are often referred to as “payroll taxes.” These payroll taxes are in addition to any income taxes that the worker must pay.

Separate payroll taxes finance Social Security’s retirement and survivors benefit program, Social Security’s disability benefit program, and Medicare; yet the three are often lumped together as one line item under “FICA” (see below) on a worker’s pay stub. The two Social Security taxes are paid only on income up to a certain annual amount. Medicare taxes are collected on all earned income.

In 2014, workers and employers will pay payroll taxes totaling 15.3 percent of the first $117,000 of income and 2.9 percent of income above that amount. The $117,000 dividing line is called the “earnings limit”—sometimes referred to as the “wage cap.” Of that 15.3 percent total, 10.6 percent of income pays for Social Security’s retirement and survivors program, and 1.8 percent pays for Social Security’s disability program. The remaining 2.9 percent is used to pay for Medicare programs, but the Medicare taxes are not subject to the earnings limit. In other words, Medicare taxes are collected on all of a worker’s earned income, not just the first $117,000.

The worker and the employer each pays half of the payroll taxes. The self-employed pay both portions.

FICA Defined. The paycheck stubs provided by most employers do not show the individual amounts that the worker pays for Social Security and Medicare. Instead, these taxes are lumped together and shown as a deduction for “FICA”—the Federal Insurance Contributions Act. FICA is the part of the Internal Revenue Code that gives the federal government the authority to collect the payroll taxes that pay for the Social Security programs and part of Medicare. The name implies that the taxes for these programs are actually contributions to a social insurance system. In reality, they are nothing more than taxes, and it would be more honest to refer to them as such.

Matching Deductions by the Employer. In most cases, only half of the Social Security taxes that a worker pays are shown on the paycheck stub. Employers pay an equal amount of payroll taxes on the worker’s behalf. As far as the employer is concerned, these additional taxes are part of the worker’s pay. Even though the worker never sees this income, the employer pays $10,765 for each $10,000 the worker earns ($10,000 in wages, $765 in payroll taxes).

Were this money not paid to the government as payroll taxes, it could go to the worker as wages. For this reason, both halves of the FICA tax should be counted as being paid by the worker. Thus, instead of paying taxes equal to 5.3 percent of income for retirement and survivors benefits, the worker is actually paying 10.6 percent of income. The combined total is the true cost to each worker.

Self-Employed Workers. This reality is clearly illustrated by self-employed workers, who must pay both the employer’s and the employee’s halves of the payroll taxes. Combining the payroll taxes for Social Security’s retirement and survivors program, Social Security’s disability program, and Medicare, the self-employed will pay a total of 15.3 percent of income below $117,000 in 2014. Moreover, they will pay an additional 2.9 percent of income between $117,000 and $200,000 ($250,000 for joint filers) and 3.8 percent of income above those income thresholds for Medicare. These payroll taxes are in addition to any income taxes.

Retirement and Survivors Tax. The largest portion of FICA payroll taxes is used to pay for a worker’s retirement and survivors benefits. The taxes pay for both the monthly benefits to workers who have retired and the monthly benefits (after the worker’s death) to the surviving spouse and children (under the age of 18). The worker and employer each pay 5.3 percent for a total of 10.6 percent of income up to the earnings limit for these programs. These taxes go into the OASI Trust Fund.

Disability Tax. Additional disability taxes equal to 1.8 percent of income (up to the earnings limit) go into the Disability Insurance (DI) Trust Fund, which pays monthly benefits to those who are unable to continue to work due to a long-term physical or mental disability. As with all payroll taxes, half of the amount (0.9 percent of income) is deducted from the worker’s pay, and the employer pays the other half on the worker’s behalf.

The Earnings Limit. In 2014, Social Security taxes will be collected on only the first $117,000 that a worker earns. This figure, the “earnings limit,” is adjusted each year. Social Security benefits are paid only on the amount of income that is subject to the Social Security payroll tax. Thus, in Social Security’s eyes, both Michael Jordan and Bill Gates earn $117,000 per year regardless of their actual incomes, and their Social Security retirement benefits will reflect this.

The earnings limit protects Social Security from having to pay benefits on Bill Gates’s entire income. It allows the program to cover all Americans without paying much higher benefits to the very rich than to average-income workers. Every October, the Social Security Administration calculates and announces the earnings limit for the following calendar year, based on the growth of wages in the economy. Wage growth is slightly higher than the rate of inflation (growth of prices).

Income Taxes on Some Social Security Benefits. Since 1983, retirees with annual income above a certain amount have been required to pay income taxes on a portion of their Social Security benefits. About one-third of Social Security beneficiaries are subject to tax. The money raised is returned to Social Security or Medicare.

Retirees with taxable income of $25,000 to $34,000 who file as individuals may have to pay income taxes on up to 50 percent of their benefits. If they have more than $34,000 in combined income, they may have to pay income taxes on up to 85 percent of their benefits. Married retirees whose combined income is between $32,000 and $44,000 may have to pay income taxes on up to 50 percent of their benefits, and if it is more than $44,000, up to 85 percent of their benefits may be taxable. These thresholds are not indexed for inflation. Income taxes on Social Security benefits are paid at the same rates as on other types of earned income.

Until 1983, all Social Security benefits were income-tax free. In that year, Congress decided to tax 50 percent of the Social Security benefits of workers with total retirement incomes over $25,000 (for single retirees) because the Social Security program needed additional revenue. Congress justified the move by pointing out that the half of payroll taxes paid by employers can also be deducted from the employers’ corporate income taxes, while workers must pay income taxes on the amount of their check that is deducted as payroll taxes. Congress decided that since companies received a tax deduction on the amount of payroll taxes paid on behalf of their workers, Congress could recapture that tax benefit by assessing income taxes on half of some retirees’ benefits. The money raised from this tax goes to the Social Security trust fund.

In 1993, problems with financing Medicare led Congress to raise the proportion of Social Security benefits that is subject to income taxes to 85 percent for workers with incomes over $34,000 (for single retirees). The money raised from this tax goes to the Hospital Insurance Trust Fund.

3. The Social Security Trust Funds

Contrary to popular belief, workers paying Social Security payroll taxes today are not contributing to their own Social Security benefits in the future. There is no Social Security account in a worker’s name that contains cash or investments. There is only a bookkeeping record of an individual’s yearly earnings and payroll taxes. Today’s workers are financing Social Security benefits for today’s beneficiaries. This is referred to as a pay-as-you-go system.

Social Security’s trust funds do not contain cash or saleable assets. They represent the amount of Social Security taxes collected in the past beyond the amount needed to pay benefits. The excess funds were converted by law into special-issue Treasury bonds that pay interest at the same rate as other bonds issued for sale to the general public. These bonds cannot be sold and can only be repaid through higher taxes on future workers. The annual surpluses that many thought were being used to build up a reserve for baby boomers have been spent to fund other government programs.

The OASI and DI Trust Funds. Social Security has two trust funds: the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund and the Disability Insurance (DI) Trust Fund. These two trust funds are linked and are often referred to as a single trust fund, the Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI) Trust Fund.

Despite the fact that there are two trust funds, most of the estimates of Social Security’s finances use the combined OASDI Trust Fund, which is an important distinction. For instance, according to the 2013 trustees report, OASDI spent $43.7 billion more in benefits than it took in through its payroll tax. This deficit is in addition to a $45 billion gap in 2010 and an expected average annual gap of about $103 billion between 2012 and 2018. These deficits will quickly balloon to alarming proportions. After adjusting for inflation, annual deficits will reach $153.6 billion in 2020 and $331.3 billion in 2030 before the trust fund runs out in 2033. Considered separately, the OASI Trust Fund spent $9.6 billion more than it took in that year with the remainder of the combined deficit resulting from the financially plagued DI Trust Fund. In addition to the two Social Security trust funds, there is a Hospital Insurance (HI) Trust Fund that partially funds Medicare. The HI Trust Fund is managed and invested in the same way as the OASI and DI Trust Funds but is outside the scope of this paper.

The Trustees and Their Annual Report. The same trustees manage the OASI, DI, and HI Trust Funds. Three of the six trustees are Cabinet officials: the Secretary of the Treasury, the Secretary of Labor, and the Secretary of Health and Human Services. The Secretary of the Treasury serves as the managing trustee. In addition, the Commissioner of Social Security is a trustee, and two public trustees are appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate for four-year terms.

Currently, the two public trustees are Charles Blahous and Robert Reischauer. Every year, the trustees are required to issue a report that details both the financial activities in the trust funds and the long-term and short-term outlooks for Social Security’s programs. Available from the Social Security Administration both online and as published copies, these annual reports contain a wealth of numbers, statistics, and predictions. In addition to the numbers from the most recent year, the reports predict Social Security’s financial status for both the next 10 years and the next 75 years. The trustees have also developed a perpetual measure that extends well beyond the 75-year measure, because a 75-year measure alone could leave the system on a path that would result in huge new deficits just one year beyond that 75-year horizon.

The report includes predictions based on the most likely economic scenario as well as both more optimistic and more pessimistic outcomes. Some analysts make the mistake of assuming that the three outcomes are equally likely to happen. A deeper analysis shows that there is only an extremely small chance (about 5 percent) that either the optimistic or the pessimistic outcome will happen, while there is a very high chance (about 95 percent) that the most likely outcome will occur. For that reason, the most recent trustees reports include a stochastic analysis that shows the probabilities of each outcome’s occurring.

Often, press reports focus on the simplest statistics, such as the year in which the trust funds are predicted to run out of assets. A more careful examination reveals other important information, such as the amount that the Social Security program owes in promised benefits beyond what it can pay with payroll taxes. The report also indicates the year in which the programs must begin to spend more than they receive in payroll taxes. These are actually more important to determining the programs’ ability to meet the needs of those who depend on them.

The OASI Trust Fund. The Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund—by far the larger of the two Social Security trust funds—pays retirement and survivors benefits. In 2012, the OASI Trust Fund had a total income of $731.1 billion. Of that total, $503.9 billion (68.9 percent) came from payroll taxes; $26.7 billion (3.7 percent) came from income taxes paid on higher-income retirees’ Social Security benefits; and $102.8 billion (14.0 percent) came from interest paid on special-issue Treasury bonds in the trust fund. The interest payment comes from general revenue tax dollars and is actually paid only to the extent that the money is needed to cover cash-flow deficits. The remainder is merely credited to the trust fund in a paper transaction.

During 2012, the trust fund paid out $637.9 billion in benefits (101.5 percent of tax receipts) and $3.4 billion (0.54 percent) for administrative expenses. Excluding the interest, the retirement and survivors program took in $628.3 billion but paid out $637.9 billion in benefits and other expenses, leaving a cash-flow deficit of $9.6 billion for 2012. The trust fund’s assets grew from $2.524 trillion at the beginning of the year to $2.61 trillion at the end of 2012.

The Disability Insurance Trust Fund. The DI Trust Fund—the smaller of the two Social Security trust funds—pays disability benefits. In 2012, the DI Trust Fund had a total intake of $109.1 billion. Of that total, $85.6 billion (78.5 percent) came from payroll taxes; $600 million (0.55 percent) came from income taxes paid on higher-income workers’ disability benefits; and $6.4 billion (5.87 percent) came from interest paid on special-issue Treasury bonds in the trust fund.

During 2012, the trust fund paid out $136.9 billion (159.9 percent of tax receipts) in benefits and $2.9 billion (3.39 percent) for administrative expenses. As a result, the trust fund’s assets shrank from $153.9 billion at the beginning of the year to $122.7 billion at the end of 2012.

The disability program’s separate trust fund and tax structure, combined with the completely different eligibility criteria for receiving disability benefits, distinguish it from the retirement and survivors program. The disability program is a true insurance program, while the retirement and survivors program is much closer to a universal entitlement.

How the Social Security Trust Funds Differ from Real Trust Funds. Private-sector trust funds invest in real assets, ranging from stocks and bonds to mortgages and other financial instruments. Assets are held only for a specific purpose, and the fund managers are liable if the money is mismanaged. Funds are managed in order to maximize earnings within a pre-agreed risk level. Investments are chosen to provide cash at set intervals so that the trust fund can pay its obligations.

The Social Security trust funds are very different. As explained by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB):

The Federal budget meaning of the term “trust” differs significantly from the private sector usage…. [T]he Federal Government owns the assets and earnings of most Federal trust funds, and it can unilaterally raise or lower future trust fund collections and payments, or change the purpose for which the collections are used…. [T]he Social Security trust funds are “invested” only in a special type of Treasury bond that can only be issued to and redeemed by the Social Security Administration. These bonds cannot be sold to the public to raise money. They are only a measure of what the government owes itself.[3]

As the Congressional Research Service noted: “When the government issues a bond to one of its own accounts, it hasn’t purchased anything or established a claim against another entity or person. It is simply creating a form of IOU from one of its accounts to another.”[4]

As a result:

These [trust fund] balances are available to finance future benefit payments and other trust fund expenditures—but only in a bookkeeping sense. These funds are not set up to be pension funds, like the funds of private pension plans. They do not consist of real economic assets that can be drawn down in the future to fund benefits. Instead, they are claims on the Treasury, that, when redeemed, will have to be financed by raising taxes, borrowing from the public, or reducing benefits or other expenditures. The existence of large trust fund balances, therefore, does not, by itself, make it easier for the government to pay benefits.[5]

In short, the Social Security trust funds are really an accounting mechanism. They show how much the government has borrowed from Social Security but do not provide any way to finance future benefits.

How Money Goes to and from the Trust Fund. An employer pays taxes to the Treasury by periodically sending a check (or making an electronic transfer) that includes both income taxes and payroll taxes. The amount is sent without distinguishing between payroll and income taxes. There is also no indication of which individual employee’s taxes are being paid or how much that employee earned in income.

On a regular basis, the Treasury estimates how much of its aggregate tax collections are due to Social Security taxes and credits the trust funds with that amount. No money actually changes hands: This is strictly an accounting transaction. These estimates are corrected after income tax returns show how much in payroll taxes was actually paid in a specific year. In addition, the Treasury credits the trust funds with interest paid on its balances and with the amount of income taxes that higher-income workers pay on their Social Security benefits.

The Social Security Administration directs the Treasury to pay monthly benefits, and that amount is subtracted from the total in the trust funds. Any remainder is converted into special-issue Treasury bonds, which are really nothing more than intra-governmental IOUs.

After the trust fund has been credited with the IOUs, Social Security’s extra tax revenue is then spent by the Treasury just as any other taxes are spent. If the federal budget is running a surplus, that amount could be used to repay federal publicly held debt. Otherwise, it is spent on any other type of federal program, ranging from aircraft carriers to education research.

Special Securities Issued to the Trust Funds. The Social Security trust funds consist solely of special-issue Treasury bonds. These bonds are special in that they can only be issued to and redeemed by the Social Security trust funds. They cannot be sold in the open market.

The Social Security trust fund bonds pay the same interest rate as regular Treasury bonds issued on the same day with the same maturity date. When the bonds mature, they are rolled over into new bonds that include both the original issue amount and any interest due. The new bonds also pay the same interest rate as comparable Treasury bonds.

Because these are special-issue bonds that are payable only to the Social Security Administration, the Social Security Administration cannot sell them to a third party to raise money to pay benefits. They can only be repaid with general revenue tax dollars that would otherwise go to pay for other government programs. This reinforces the fact that these bonds are really nothing more than IOUs from one branch of government to another. They are not a real financial asset.

Until relatively recently, these bonds existed only as entries in a record book. Now, when a new bond is issued, it is printed on a laser printer located at the Bureau of the Public Debt in Parkersburg, West Virginia. The bond is then carried across the room and put in a fireproof filing cabinet. That filing cabinet is the Social Security trust fund.

How Trust Fund IOUs Would Be Repaid. In 2010, Social Security began to pay more in benefits than it received from payroll taxes. At that point, it began to spend a portion of the interest that was credited to the special-issue bonds in its trust funds. According to the most recent trustees report, this situation will continue until 2020, when Social Security will need a larger amount of additional income than it will receive from interest payments. Starting in 2020, Social Security will redeem about $2.7 trillion (in 2012 dollars) in special-issue bonds, cashing the first special-issue bond in 2020 and the last bond in 2033.

According to the OMB, there are only four ways that Congress can repay these bonds: (1) raise other taxes; (2) authorize the Treasury to borrow the needed funds from the public; (3) reduce spending on other federal programs and use the savings to redeem Social Security’s bonds; or (4) simply reduce Social Security benefits. None of these options is easy or attractive.

4. Determining Social Security Benefits

Social Security benefits are based on earnings averaged over most of a worker’s lifetime. Most people know about Social Security retirement benefits, but the program also pays benefits to disabled workers. In addition, families can receive benefits under certain circumstances. The formula that the agency uses to determine the benefits for a worker or the worker’s family is complex. Complicating matters even more are a number of special circumstances that can alter those benefits.

What follows is a general analysis that is suitable for policymakers. For individual cases, it would be wiser to seek guidance from the Social Security Administration or other sources.

When Can a Worker Retire? There are two answers to this question. A worker can collect partial Social Security retirement benefits as early as age 62 but cannot receive full retirement benefits until ages 65 to 67, depending on date of birth. Workers born before 1938 can receive full retirement benefits starting at age 65. The full retirement age increases by two months per year for workers born between 1938 and 1942 and is 66 for those born between 1943 and 1954. The full benefits age then increases by two months per year for those born between 1955 and 1959 and is 67 for anyone born in 1960 or later.[6]

If a worker decides to collect benefits starting at age 62, the monthly payments will be reduced by a set percentage for each month that the worker receives benefits before full retirement age. As the full retirement age increases from 65 to 67, workers who retire early will receive an even greater reduction in their monthly benefits. A worker with a full retirement age of 65 who retires at 62 will receive 80 percent of the full retirement amount. A worker with a full retirement age of 66 retiring at 62 would see his Social Security benefits reduced by about 25 percent.[7] This will eventually drop to 70 percent for those with a full retirement age of 67.

Workers may also increase their benefits by working beyond the full retirement age. Benefits increase by about 8 percent for every year until age 70, in which the worker does not receive Social Security. Once a worker turns 70, Social Security benefits do not increase further.

Qualifying for Retirement Benefits. To qualify for Social Security benefits, a worker must earn at least 40 quarterly credits—10 years’ worth of payroll tax payments. A worker earns one credit by earning at least $1,200 in a three-month period and paying Social Security taxes on that amount. Workers who earn $4,800 during a year earn four credits.

The amount of income required to earn a credit is adjusted annually, but this does not affect credits that have already been earned. Once a worker has earned the required 40 credits, he or she is permanently qualified. However, the level of benefits depends on income history.

The Disability Insurance program has similar requirements, but the number of credits necessary to qualify varies depending on the age at which the worker becomes disabled. In general, the younger the person, the lower the number of credits required to qualify for benefits.

The General Formula for Retirement Benefits. Retirement benefits are based on a worker’s highest 35 years of earnings. Those wages are indexed so that they have the purchasing power of the year when the person retires. The worker’s Average Indexed Monthly Earnings (AIME), or average monthly salary, is calculated using the 35 years of indexed earnings. The AIME is then run through a formula that calculates benefits equal to 90 percent of AIME up to a certain level of monthly income ($816 in 2014); 32 percent of AIME from that level to a higher point (between $816 and $4,917 in 2014); and 15 percent of the remaining AIME.

The dividing points between the three payment levels are known as “bend points.” The three payment levels are added up to find the worker’s monthly Social Security retirement benefit. Both steps are detailed below.

Determining Average Indexed Monthly Earnings (AIME). Retirement benefits are calculated using a worker’s highest 35 years of earnings. They do not have to be consecutive years. If the worker has an earnings record for more than 35 years, only the 35 years of highest earnings are included in the calculation; years with lower earnings are dropped. Only those earnings on which the worker paid Social Security taxes are counted. Thus, if the worker earned $120,000 in 2014, that year’s income would be counted as $117,000 for determining benefits, since the worker paid Social Security taxes only on the lower amount.

Earnings for previous years are indexed so that all years are measured by the same ability to purchase goods and services. Social Security uses the average wage index for two years prior to retirement. Thus, a person retiring in 2013 would see his wages through 2011 indexed to the 2011 average wage index; the two years immediately before retirement, in this case 2012 and 2013, are not indexed. This indexing increases past earnings to account for inflation as well as increases in average wage growth. For instance, it would take $5.67 in 2013 dollars to equal $1.00 earned in 1973 and $2.04 to equal $1.00 earned in 1990.[8]

Once the 35 years of highest earnings are determined, they are totaled and divided by 420 (the number of months in 35 years). The result is the AIME, which is used to calculate Social Security benefits.

Some jobs—usually for state or local governments or certain religious organizations—are not covered by Social Security, and earnings for those jobs are not included in calculated AIME. For the purposes of determining Social Security benefits, those years count the same as if the worker was not employed.

If a worker did not work for a full 35 years—perhaps due to raising a family or because of illness—the missing years are counted as zeros. For example, if a worker is either employed for only 25 years or worked in a job covered by Social Security for only 25 years, the indexed earnings from those 25 years are added together and divided by 420—lowering that worker’s AIME to account for the missing years. Social Security benefits earned by state and local government workers are adjusted in other ways, as explained below under “The Government Pension Offset” and “The Windfall Elimination Provision.”

Wage Indexing vs. Price Indexing. In creating AIME, a worker’s past wages are indexed to bring them to the same level as today’s earnings. There are two general ways to index past earnings and potentially dozens of variations on these two that would create results that lie between the two general methods. This calculation is done only once in a worker’s life—when he or she first applies for Social Security benefits. Once the worker’s initial monthly benefit has been determined, it is price indexed in each successive year to protect the retiree from inflation.

Price indexing is based on the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and compensates for inflation. Price indexing benefits ensures that they maintain their constant purchasing power. In this case, if inflation had increased by 5 percent since last year, simply multiplying the previous year’s benefit by 1.05 to reflect inflation would preserve the retiree’s ability to buy the same amount of goods as last year. His monthly benefit, for instance, would go from $1,000 to $1,050. However, there are several potential ways to measure prices, each of which produces a slightly different result. Social Security has used the same index since cost-of-living adjustments first started in 1975, but there is controversy about whether it is the best index to use.

By contrast, wage indexing is based on the growth in average wages in the economy over a set period of time and is supposed to allow workers to retire with the same standard of living. The growth in average wages includes both inflation and growth in the overall economy. As a result, wage indexing almost always results in a higher AIME than price indexing. Social Security uses wage indexing only when calculating AIME, determining the annual level of bend points in the benefit level, and determining the annual level of the payroll tax earnings cap.

The difference between the two forms of indexing can be important. If someone worked as a bricklayer throughout his career and earned $4.00 per hour in 1980, indexing that amount for inflation (an increase of 163 percent) would result in an indexed wage of $10.55 per hour. On the other hand, indexing for average growth in wages (an increase of 243 percent) would result in $13.73 per hour. While it is true that $10.55 in 2013 would buy the same amount as $4.00 in 1980, the average wage for a bricklayer could have increased to something closer to $13.73 per hour in 2013.

Wage indexing allows retirees to take advantage of the increase in the standard of living over their working careers. However, it is often criticized as giving workers a retroactive credit for improvements in the economy. In other words, the worker’s 1980 wages are being measured according to the standards of the 2013 economy rather than according to the standards of the 1980 economy in which they were earned.

The key difference lies in replacement rates. The replacement rate is the proportion of a worker’s average monthly earnings that is paid by that worker’s Social Security retirement benefit. Currently, Social Security pays average-income workers a retirement benefit equal to between 39.8 percent and 42.9 percent of their average monthly earnings. Lower-income workers generally receive a higher proportion of their average monthly earnings, while higher-income workers receive a lower proportion. However, the amount that an individual actually receives may be altered because Medicare premiums are deducted from Social Security benefits before they are sent to the recipient.

With wage indexing, these basic replacement rates will remain roughly stable. On the other hand, changing to price indexing will gradually reduce the replacement rates. While this would bring promised Social Security benefits closer to what the program can afford to pay, it would also require workers to make up the difference from savings or some other form of retirement plan. Most experts believe that a retiree needs an income equal to roughly 70 percent to 80 percent of pre-retirement income for a comfortable retirement.

Annual Cost-of-Living Adjustment (COLA) Increases. Once a worker’s monthly benefits have been determined, they are increased every year by the rate of inflation. This cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) is intended to preserve the purchasing power of a recipient’s benefits. The amount of the annual increase is announced each October and takes effect the following January.

COLA is based on the inflation rate for the preceding 12 months from October 1 to September 30. For example, in October 2013, the Social Security Administration announced a COLA increase of 1.5 percent for all checks issued after January 1, 2014. This increase was based on the change in the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W) from October 1, 2012, through September 30, 2013. If there is no increase in inflation during that calculation period, there are no new COLAs until the inflation index is higher than it was at the end of the previous measuring period.

The Social Security Administration currently uses the Department of Labor’s CPI-W to measure inflation, but the law allows it to substitute other inflation indexes or the annual increase in average wages under some circumstances.

A more accurate index is now available than was available when Social Security first implemented its COLA. In 1975, the Bureau of Labor Statistics published only the CPI-W. It is based on prices paid by urban wage workers and clerical workers, who make up only 32 percent of the population. The broader Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U), from which the chained CPI is derived, covers 87 percent of the population. The CPI-W is not only outdated and covers only a small subset of the population, but also fails to account for how consumers respond to changing prices.

The chained CPI more accurately measures the cost of living by correcting existing flaws that allow inflation-adjusted benefits to rise in both absolute and relative purchasing power over time. Excess COLA increases from the current flawed index are contributing to Social Security’s long-term fiscal insolvency. Lawmakers could eliminate about one-fifth of Social Security’s long-term fiscal imbalance by implementing a chained-CPI COLA. However, if lawmakers allow Social Security benefits to continue to increase faster than the cost of living, the excess payments will result in earlier and deeper cuts for Social Security recipients, beginning in less than 20 years.[9]

Using Bend Points to Calculate the Monthly Benefit. Once an AIME has been determined, the Social Security Administration calculates a worker’s monthly retirement benefit using a formula that pays a higher benefit relative to income to lower-income workers than to higher-income workers. In 2014, Social Security will pay 90 percent of the first $816 of a worker’s AIME, 32 percent of the AIME amount between $816 and $4,917, and 15 percent of any AIME amount over $4,917. The Social Security Administration adjusts these bend points each year.

The bend points ensure that a lower-income worker receives Social Security retirement benefits that are comparatively higher than the pre-retirement income that an upper-income worker receives. For example, a worker with an AIME of $5,000 (that is, average annual income of $60,000) would receive 90 percent of the first $816 ($734.40); 32 percent of the amount between $816 and $4,917 ($1,312.32); and 15 percent of the amount between $4,917 and $5,000 ($12.45). Thus, the worker’s monthly benefit would be $2,059.17, or about 41.1 percent of AIME.

On the other hand, a worker with an AIME of only $1,600 (or an average annual income of $19,200) would receive 90 percent of the first $816 ($734.4) and 32 percent of the amount between $816 and $1,600 ($250.88), for a total monthly benefit of $985.28. This lower monthly benefit amount would equal 61.6 percent of the AIME.

5. Special Provisions

The Social Security program has eight special provisions:

The Spousal Benefit. In addition to the retirement benefits that a worker can receive, the worker’s spouse can also receive a benefit in some circumstances. Most spouses who qualify for the full benefit come either from single-earner families in which one spouse was employed and the other stayed at home to care for the family or from situations where there was a large difference between the earnings of the two. The spousal benefit is equal to 50 percent of the employed spouse’s benefit, which means that such families could receive a total Social Security income of 150 percent of the working spouse’s benefit while both are still alive.

The “dual-entitlement rule” prevents spouses who qualify for their own Social Security retirement benefits from receiving both their own benefits and a spousal benefit. An exception is made if the lower-earning spouse’s benefits are less than 50 percent of the higher-earning spouse’s benefits. In that case, the lower-earning spouse would also qualify for a spousal benefit equal to the difference between his or her retirement benefits and 50 percent of the higher-earning spouse’s benefits.

Some special circumstances—for example, if one spouse was employed by a state or local government that does not participate in the Social Security program—can make it appear that someone qualifies for spousal benefits even though he may have substantial income or retirement benefits from the job not covered by Social Security. The Government Pension Offset addresses this circumstance and limits spousal benefits to families that qualify for it.

Survivors Benefits. The amount of the survivors benefits paid to spouses, including divorced spouses if the marriage lasted at least 10 years, and children under the age of 18 (19 if still attending high school) depends on the earnings history of the deceased worker. The same formula that calculates retirement benefits is also used for survivors benefits. They are usually calculated as a percentage of the benefit for which a worker would have been eligible at the time of death.

Surviving spouses who are near retirement age receive a benefit that is based on the worker’s retirement benefit. If the worker began to receive benefits at full retirement age, the surviving spouse will receive an amount equal to 100 percent of the worker’s benefits. This is also true if the worker died before receiving Social Security. However, if the surviving spouse is also entitled to receive benefits, he or she will receive only the larger of the two amounts. The survivor will not receive both the worker’s benefit and his or her own benefit.

If the deceased worker received a reduced amount of retirement benefits before full retirement age, the surviving spouse will also receive a reduced monthly benefit. The exact amount depends on the survivor’s age and the level of the worker’s benefit. A surviving spouse can receive benefits as young as age 60 (50 if the surviving spouse is disabled) but in that case would receive only 71.5 percent of the worker’s full retirement benefit.

In addition to the monthly benefit, surviving spouses receive a one-time $255 death benefit. This benefit is payable only to spouses or children eligible to receive benefits.

Another situation occurs if the worker dies leaving children under the age of 18. In that case, both the children and the surviving spouse are eligible to receive a benefit equal to 75 percent of the retirement benefit for which the worker qualified at the time of death. Children and the spouse continue to receive this benefit until the last child reaches age 18 (19 if the child is in high school at that date or at any age if the child is disabled before turning age 22). The total annual amount that the family can receive from Social Security depends on a number of factors and lies between 150 percent and 180 percent of the worker’s full retirement benefit. Once the last child has reached an age at which benefits end, benefits also end for the surviving spouse until he or she qualifies for retirement benefits.

Disability Benefits. Disability benefits are calculated using the same formula as the one used to calculate retirement benefits. However, disability benefits for a worker who is disabled before having worked 35 years are calculated using a shorter work history so that the worker is not penalized.

Obtaining approval for Social Security disability benefits is not easy. The Social Security Administration’s definition of disability is extremely strict, and about half of the workers who apply for benefits are turned down. Some of these applicants will be approved on appeal, but the process can be long and complicated.

To qualify, a worker must be unable to do any kind of substantial work because of physical or mental disabilities, which are expected either to last at least 12 months or to result in death. Merely being unable to do the job that he or she held before the disability does not automatically qualify someone for disability benefits. Depending on the worker’s age, experience, and education, a person may be regarded as qualified for other work and thus be denied disability benefits, even if the work is at a lower salary. Family members may also be eligible to receive benefits because of a worker’s disability.

Because the disability insurance program functions as a true insurance program with its own tax, trust fund, and eligibility process, it is considered separate from Social Security’s retirement and survivors program.

The Retirement Earnings Limit: Working During Retirement. At one time, any worker under the age of 70 who received Social Security retirement benefits and chose to return to work would lose a substantial portion of his or her Social Security benefits. In 2000, Congress eliminated this penalty for workers who have reached full retirement. Workers between 62 and full retirement age still risk losing much or most of their benefits if they choose to work after applying for retirement benefits.

In 2014, workers under full retirement age can earn up to $15,480 without any consequences. However, for every two dollars they earn over that amount, their Social Security benefits are reduced by one dollar. A higher limit of $41,400 applies to the year in which the worker reaches full retirement age.

Rather than reducing each monthly benefit equally, Social Security frontloads the reduction until the full amount of the reduction is reached. Thus, if annual benefits were to be reduced by $4,500 and a worker’s monthly benefit was $1,000 per month, that person would not receive Social Security checks for the first four months, and the check for May would be for only $500. Starting in June, the worker would again receive $1,000 per month through December.

The Government Pension Offset. The Government Pension Offset affects the Social Security benefits for spouses of workers who held jobs that were not covered by Social Security. Most of these workers were either state or local government employees or were federal employees prior to 1984. Since government workers who were not covered by Social Security do not have an earnings record for those jobs or any Social Security benefits based on that employment, they would theoretically qualify for a full spousal benefit, even though the spouse would not qualify if both workers had been part of Social Security.

Thus, a person who joined the federal government prior to 1984 would, in theory, be able to receive both a full Civil Service Retirement System (CSRS) pension and a Social Security spousal benefit. To eliminate this dual benefit, Congress created the Government Pension Offset in 1977.

Under the Government Pension Offset, two-thirds of the CSRS pension (or, in other cases, the pension that comes from a state or local government that does not participate in Social Security) is treated as if it were a Social Security benefit, and the worker’s Social Security spousal benefit is reduced dollar for dollar by this amount.

For example, if the CSRS worker’s spouse receives $1,200 per month from Social Security, the worker would technically be eligible for a Social Security spousal benefit of $600 (one-half of the spouse’s basic retirement benefit). However, if the worker has a $1,200 per month CSRS pension, $800 of his or her pension (two-thirds) would be treated as coming from Social Security. This would eliminate the spousal benefit because two-thirds of the CSRS pension ($800) is larger than the potential spousal benefit ($600).

As a result of the Government Pension Offset, the CSRS worker and the worker’s spouse are treated the same as married workers who are both covered by Social Security. The Government Pension Offset affects about 600,000 retirees and reduces Social Security’s aggregate benefits by approximately $4 billion annually. A major proportion of those affected by this rule are retired federal workers; most of the rest were employed by state and local governments that do not participate in Social Security. The vast majority of these workers come from eight states: Alaska, California, Colorado, Louisiana, Maine, Massachusetts, Nevada, and Ohio.

The Windfall Elimination Provision. The Windfall Elimination Provision is similar to the Government Pension Offset, except that it applies to the worker’s retirement benefits instead of spousal benefits. It applies only to workers who have both a Social Security retirement benefit and a pension from a job that was not part of Social Security.

Under the Windfall Elimination Provision, only 40 percent (as opposed to the usual 90 percent) of the first $816 (the first bend point in 2014) of the AIME is counted toward the worker’s monthly retirement benefit. This in turn lowers the affected worker’s total monthly benefit. For example, the monthly benefit for a worker with an AIME of $1,200 would be reduced from $857 to $449, and a worker with an AIME of $4,000 would receive $1,345 per month instead of $1,753.

There are exceptions to this provision that take into account how long the worker was employed in a job covered by Social Security. The longer a worker was employed in a job covered by Social Security, the lower the benefit reduction. If the worker received “substantial” Social Security–covered earnings for 30 years or more, there is no reduction in benefits. In the case of a worker covered by Social Security for 21 years to 29 years, the 90 percent multiplier would be reduced to between 45 percent and 85 percent, depending on the exact number of years worked.

The Windfall Elimination Provision adjusts the benefit formula to reflect retirement income from employment not covered by Social Security. It was created because the basic Social Security benefit formula is designed to give lower-income workers more for their Social Security taxes than higher-income workers. If a government worker spent 30 years in a job not covered by Social Security and only 12 years in one that is covered, his or her Social Security earnings record (AIME) would appear to be very low when compared to his or her actual average income from both jobs. This is because all of the income not covered by Social Security would be excluded from the AIME calculation. Without this provision, a middle-income or even upper-income worker would receive a Social Security benefit based on a low-income worker’s higher replacement rate.

The Dual-Entitlement Rule. A long-standing principle of Social Security holds that a worker cannot qualify for both full retirement benefits and full spousal benefits. Accordingly, although a married worker theoretically qualifies for both retirement benefits from his or her own earnings record and a spousal benefit equal to 50 percent of the spouse’s retirement benefit, the dual-entitlement rule limits the spousal benefit.

The dual-entitlement rule reduces the spousal benefit dollar for dollar by the amount of the retirement benefits for which a worker qualifies under his or her own earnings record. Thus, if two spouses each qualify for $1,200 per month from their own earnings records and for spousal benefits of $600 per month (one-half of the basic retirement benefit), they would still receive a total benefit of only $2,400 ($1,200 per person). Both spouses are ineligible for the $600 spousal benefit because their individual retirement benefits are greater.

On the other hand, if one spouse received $1,200 per month and the other received $400 per month from Social Security, the lower-earning spouse would qualify for a $200 spousal benefit. In this case, the $600 spousal benefit from the higher-earning spouse would be reduced by the lower-earning spouse’s benefit ($600–$400), leaving a $200 spousal benefit. Currently, 27 of 100 women who receive Social Security payments are affected by the dual-entitlement rule. As even more women enter the workforce and stay in it longer, the dual-entitlement rule is projected to affect over one-third of women by 2025.[10]

Notch Babies. “Notch babies” are workers who were born between 1917 and 1921. Due to a technical error in a 1972 law, they receive slightly lower benefits than workers born before 1917, although they also receive slightly higher benefits based on their earnings record than workers born after 1921. As a result, legislation was regularly introduced in Congress that would have either raised their benefits or provided them with a lump-sum payment.

However, a 1994 commission found that, although notch babies do receive slightly lower benefits than workers born before them, notch babies receive a fair return for their taxes. As a result, no legislation concerning notch babies has been passed, a situation that is unlikely to change.

Notch babies get their name from a line graph showing average benefits by age of birth. Because those born between 1917 and 1921 tend to receive slightly lower benefits than those born before them, the line has a slight notch for those years.

The problem was caused in 1972 when benefits were first indexed for inflation. Congress made a technical error in writing the law that resulted in workers receiving a double adjustment for inflation. By the time Congress corrected this error in 1977, some workers had already retired with higher benefits than they should have received. Rather than lowering their benefits, Congress decided to correct the problem only for those who had not yet retired. In addition, rather than just correcting the law to lower benefits to where they should have been, Congress phased in the change over five years, affecting retirees born between 1917 to 1921.

Conclusion

Social Security is a remarkably complex program, and few people understand how it operates. In many cases, terms used by the Social Security Administration (such as trust fund) have meanings that are different from the meanings conveyed by the same terms when they are used in the private sector. If the program’s financial problems are to be mitigated, informed citizens and policymakers must measure different reform options against the existing program’s operating structure and practices.

—Romina Boccia is Grover M. Hermann Fellow in Federal Budgetary Affairs in the Thomas A. Roe Institute for Economic Policy Studies at The Heritage Foundation.