Introduction

The Index of Economic Freedom, published annually by The Heritage Foundation and The Wall Street Journal, is entering its third decade with the publication of the 21st edition. Since the first edition the world has witnessed profound advances in the cause of freedom. Open economies have led the world in a startling burst of innovation and economic growth, and political authorities have found themselves increasingly held accountable by those they govern.

Despite continuing challenges confronting the world economy, the global average economic freedom score has improved over the past year by one-tenth of a point, reaching a record 60.4 (on a scale of 0 to 100) in the 2015 Index. Although the rate of advancement has slowed in comparison with the previous year’s near record 0.7 point increase, the world average is now a full point higher than the score in the aftermath of the financial crisis and recession, thus regaining all of the ground lost.

On a worldwide basis, the increase in economic freedom was driven by improvements in trade freedom, monetary freedom, and freedom from corruption, for which global ratings have advanced by an average of close to one point or more.

Regrettably, average scores for most other economic freedoms—including business freedom, property rights, labor freedom, and financial freedom—have registered small declines. More troubling were the declines in the Index measures of government size. With a drop of 0.8, the control of government spending has recorded the largest deterioration, reflecting a continuation of countercyclical or interventionist stimulus policies in many countries.

Furthermore, the world continues to witness profoundly worrisome attacks on economic and political freedoms, for example by ISIS in the Middle East and North Africa and by Russia in Europe and Central Asia. Elsewhere, the failures of populist authoritarian regimes, such as in Venezuela, have inevitably generated economic chaos. Meanwhile, economic growth rates in the U.S., Japan, and the EU remain stagnant.

The United States continues to rank as only the 12th freest economy, seemingly stuck in the ranks of the “mostly free,” the second-tier economic freedom category that the U.S. dropped into in 2010. However, the downward spiral in U.S. economic freedom over the previous seven years has come to a halt. In the 2015 Index, the U.S. recorded modest score gains in six of the 10 economic freedoms and an overall score increase of 0.7. On the other hand, the U.S. score for business freedom plunged below 90, the lowest level since 2006.

The long slide in American economic freedom has been accompanied by stagnant growth of the U.S. economy and persistently high unemployment and underemployment. Adoption of the revitalizing policies of economic freedom in the United States is essential to creating good new jobs for Americans. It is also vital to promote economic freedom abroad because U.S. companies and workers increasingly rely on international trade and finance to improve productivity and to build markets.

America is a global economic superpower, but to maintain its position, its government and business community must encourage the free flow of capital, goods, services, and ideas around the world, which contribute to ongoing U.S. and global prosperity. Implementing such forward-looking policies would kick-start the economic dynamism and innovation that will lead to better products, new markets, and greater investment.

In this fifth annual Global Agenda for Economic Freedom, a diverse team of Heritage Foundation policy experts make key observations about eight global regions: Sub-Saharan Africa, North America (the U.S., Canada, and Mexico), the Asia–Pacific, the Middle East and North Africa, Central and South America and the Caribbean, Europe, Russia, and the Arctic. In each region, Heritage experts identify obstacles to expanding economic freedom and the actions that regional governments should take, and make concrete recommendations on roles the U.S. can take in promoting economic liberty.

While these recommendations are crafted for individual regions, some themes appear repeatedly worldwide—particularly the importance of protecting property rights, fighting corruption, and pushing back against a revival of the failed state-owned-enterprise model and creeping crony corporatism and government favoritism. These are summarized in a Global Issues section at the beginning of the report.

To help nations to achieve such goals, the report also identifies opportunities in virtually every region for the U.S. government to forge new agreements and initiatives that will promote job-creating, private sector–led trade and investment.

The emphasis on free trade is not surprising. Countries with the lowest trade barriers also have the strongest economies, the lowest poverty rates, and the highest per capita income. Thus, the “free trade tool” is an ideal instrument for expanding economic freedom. In particular, new initiatives, such as the ongoing negotiations for a Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) of 12 Pacific Rim nations as well as a Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) between the European Union and the United States, hold some promise. If negotiated well, these agreements could create new economic opportunities by expanding trade among the United States, Asia, Latin America, and the member states of the European Union.

History teaches that the human spirit thrives on fairness, opportunity, transparency, and liberty. The downfall of the Soviet Union, the liberation of Eastern Europe, the opening of China, and the ongoing “Arab Spring” are vivid reminders of this truth. The human spirit is the real wellspring of economic prosperity and enduring development, and that spirit is at its most inspired when it is unleashed from the chains that have bound it.

The fight for freedom necessitates perpetual vigilance. The false idols of socialism and collectivism in the name of social justice and equality are never short of deceptive emotional appeal. When they become the touchstones of government policy, the unavoidable economic and social results are stagnation, deprivation, coercion, and even the gradual erosion of the rule of law.

This report lays out a plan to push back against those false promises and to promote economic freedom in the world. It offers Washington a blueprint—a global agenda—for a practical and effective strategy to promote economic freedom around the world and restart growth at home. This global agenda can—and should—be implemented. Now.

—James M. Roberts and William T. Wilson, PhD, eds.

Global Issues

James M. Roberts

A World with More Trade and Investment Freedom

International trade plays an increasingly significant role in the economies of the United States and other countries. Thanks to U.S. leadership in the Uruguay Round trade talks, 123 countries collectively implemented the largest global tax cut in history and created the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995 to mediate trade disputes. Trade disagreements that could have escalated into trade wars in the past are now moderated by impartial referees. With first the U.S.–Canada free trade agreement (FTA) in the 1980s, and then the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in the 1990s, the United States initiated a healthy global contest to see which country could sign the most free trade agreements. So far, Chile is in the lead, having inked agreements with 56 countries; Mexico is second, with 44 countries. Overall, hundreds of bilateral and regional trade agreements are in force today among free-market countries, and many more are being negotiated.

However, the continuing lack of leadership by the Obama Administration has allowed negotiations for further global trade liberalization through the Doha Round (the successor to the Uruguay Round) to grind to a halt. Furthermore, the long delays during the first term of the Obama Administration in implementing the FTAs with Colombia, Panama, and South Korea severely hampered the momentum for trade liberalization in the United States.

There are some potential bright spots for global trade freedom: the ongoing Trans-Pacific Partnership talks among Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, the United States, and Vietnam. The participants’ goal is to make the TPP a “21st-century” or “gold-standard” trade agreement. To reach this goal, each country must be willing to make beneficial policy changes that will include reducing tariff and non-tariff barriers, improving protection of intellectual property and international investment rights, dismantling agricultural and many other government subsidies, and limiting support of state-owned enterprises (SOEs). The resulting agreement should include a mechanism to facilitate easy accession by other countries in the future.

Regrettably, TPP negotiations to date have included excessive U.S. posturing on environmental standards and labor regulations. Although there is a danger of further such posturing in negotiations that began in 2013 on a Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership between the European Union and the United States, there also are potential benefits from an agreement that reduces barriers to transatlantic trade and investment, as opposed to one that creates new regulatory hurdles to doing business.

Meanwhile, American trading partners, such as Canada and Chile, have forged ahead with new agreements, leaving the U.S. behind. In the regional sections that follow, Heritage Foundation experts lay out specifics of how the United States can catch up around the world. The United States should encourage other countries’ efforts to reduce trade barriers, including African countries’ proposed Continental Free Trade Area (CFTA) to boost Africa’s intraregional trade and the Alliance of the Pacific (Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru with candidate countries Costa Rica and Panama).

U.S. programs, such as the U.S. Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) and the African Growth and Opportunity Act, promote mutually beneficial trade and growth. These programs should be expanded to include more categories of imports and extended on a long-term basis. Foot-dragging by the Obama Administration has had a larger cost: the decline of the credibility of the U.S. as an economic model. Not long ago people around the world spoke of the “Washington consensus,” by which they meant a generally free-market policy mix. Now, foreign governments deride America’s slow growth and policy failures. Chinese leaders in particular look with disdain on American policy advice, notwithstanding their own rapidly mounting problems and their pressing need for another wave of economic reforms.

As documented in the 2015 Index of Economic Freedom, protectionist measures, industry-specific subsidies, and excessive (and potentially protectionist) “enforcement” actions, such as anti-dumping and countervailing-duty regulatory measures, reduce efficiency and competitiveness and diminish the prosperity of all nations. All countries should resist these counterproductive policies, and the U.S. should lead.

In an economically free country, there are no constraints on the flow of investment capital. Individuals and firms are allowed to move their resources to and from specific activities without restriction, both internally and across the country’s borders.

Regarding investment, the U.S. government should refocus its development policy on trade and investment and vigorously pursue an expanded commercial agenda that makes investment in developing countries more attractive to investors, such as by establishing a broader network of bilateral investment treaties (BITs) or trade and investment framework agreements (TIFAs) and by negotiating double-taxation treaties that remove fiscal burdens from investment-oriented capital flows.

A World with More Freedom for Workers

Labor freedom and business freedom indicators in the 2015 Index of Economic Freedom reward countries with laws, regulations, and policies that give workers and employers flexibility and opportunity. In addition, guest worker visa programs can help countries to meet growing needs for skilled technology workers or seasonal workers. These guest worker visas can also address politically difficult immigration issues.

In the United States, H1-B visas for high-tech workers help American high-tech companies to recruit skilled immigrants, such as engineers and computer programmers. Under current law, the government can issue only 85,000 H1-B visas each year: 65,000 to highly skilled private-sector workers and 20,000 to workers with advanced graduate degrees from U.S. universities. Yet demand for such skills is much greater, so the caps are reached very quickly every year.

Another pro-economic freedom measure would be to make it easier for business people to travel between countries. In the United States, expanding the Visa Waiver Program (VWP), particularly by adding member countries from trusted allies and partners of the U.S., would further reduce transaction costs and increase efficiency for American businesses. Chile has now been invited to join the VWP, but America’s great ally and trading partner Poland continues to be denied the VWP membership that it richly deserves.

The VWP has also boosted U.S. tourism receipts, since most tourist and business travel to the United States originates in countries enrolled in the Visa Waiver Program, and it is therefore an important instrument to promote economic exchange with like-minded nations. The Obama Administration should speedily approve many more eligible and deserving nations for the VWP.

A World with Less Corruption and More Property Rights

Economists from Adam Smith to Milton Friedman have noted the crucial role of property rights as an engine of economic growth, on which the equally important development of a middle class depends. Establishing those property rights is step one for economic freedom.

For nearly every country on the globe, the Index of Economic Freedom’s “freedom from corruption” score is the lowest of the 10 indicators measured. Corruption is a perennial and difficult problem to address, yet it must be a top priority for governments hoping to create conditions favorable to economic growth and prosperity. The degree of corruption in a country is a good barometer of the strength of its judicial institutions and rule of law, both of which are strongly tied to how effectively a country protects private property.

Many countries’ economic freedom scores would be substantially higher if not for the prevalence of government corruption. Yet the solution lies not in passing more anti-corruption laws, which can be corrupted in practice. In fact, too much regulation can reduce respect for the law, creating an environment for predatory behavior by the government or its favored cronies.

The best means of fighting corruption is transparency. Laws should be clear, logical, and simple to understand.

Lack of reliable property rights is a worldwide problem. The starting point for development, especially in lower-income countries, is greater agricultural productivity, which depends on secure property rights to land. These are absent in much of the world.

For example, the biggest problem in the Indian economy is uncertainty about land ownership. This affects hundreds of millions of people. Most resources associated with land belong to the state, and many attempted land sales conflict with contested ownership and require corrupt and horribly inefficient government involvement to carry out. This system undermines agricultural productivity and obstructs progress in alleviating poverty.

In dealing with developing economies, the U.S. needs to expand from focusing almost exclusively on intellectual property rights (IPR) to include land and other property rights. While the information and IPR sectors are vitally important parts of the economy in the developed world and certainly should be protected, these areas are not as mature in emerging markets and poorer nations. In developing countries, it is most vital to protect the “real” properties—land, businesses, capital, and buildings—from expropriation and corrupt practices because they are the primary sources of the commodity exports on which those countries depend.

To protect real property, developing countries must enhance their rule of law. Transparent judicial systems are vital for the protection of property rights, not just for the wealthy and powerful, but also for average citizens. Citizens’ incentive to work hard and save for the future depends on their confidence in the political and economic system to protect their earnings and possessions. The right to acquire, keep, and dispose of property at will must be protected through honest, efficient, and transparent judicial institutions so that assets can be expected to be available as needed.

Less corruption and better protection of property rights will make for much more prosperous long-term economic partners. The U.S. should offer technical assistance to strengthen the rule of law, for example, by developing appropriate legal norms and land-titling processes and for mapping property boundaries.

A World with Less Crony Corporatism and Fewer State-Owned Enterprises

The full chapter on state-owned enterprises in the Trans-Pacific Partnership is not an accident. Massively subsidized SOEs are an international issue that is steadily growing in importance, not least because of their dominance of the Chinese economy. Brazil has been backsliding in this area for several years. India has a set of poorly performing state firms associated with harmful government intervention in the economy, such as price controls. In Vietnam, underperforming SOEs are the main factor restraining development. The ideological commitment of some governments to state ownership precludes the complete eradication of SOEs, but internal and external reforms would considerably enhance economic freedom and clear the way for fresh global liberalization.

Governments should publicly identify the smallest possible set of sectors that must be managed by the state for clearly identified strategic reasons. In other sectors, state firms should be sold or at least forced to compete.

Sub-Saharan Africa

Charlotte Florance and Anthony B. Kim

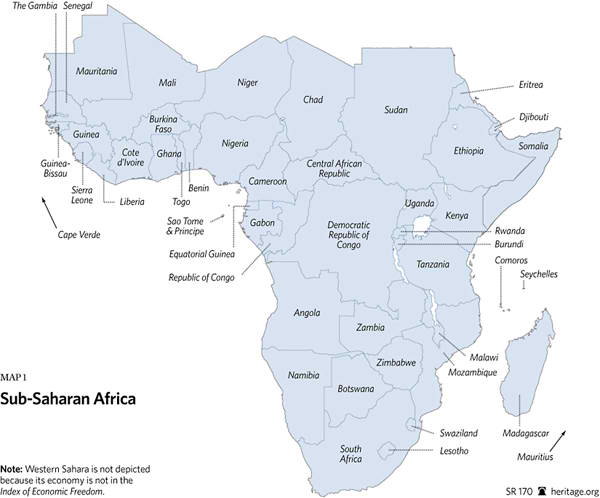

The sub-Saharan Africa region remains a global hot spot for economic, political, and security developments. Despite some setbacks caused by political turmoil and Ebola in the region over the past year, sub-Saharan Africa’s overall trade and investment environment has been evolving in a positive direction.

According to the Index of Economic Freedom the trend by sub-Saharan African economies as a group toward greater economic freedom has been gaining steam over the past decade. The 2015 Index, in particular, notes encouraging developments. With more than half of the region’s 46 countries graded in the Index having enhanced their economic freedom scores, sub-Saharan Africa is one of the most improved regions in the 2015 Index. Indeed, six of the 10 largest score improvements among all 178 countries graded in the 2015 Index were registered by sub-Saharan African countries. More impressively, a number of countries in the region, including Angola, Comoros, Guinea-Bissau, and Seychelles, have shown sustained growth in economic freedom over the past five years. Also encouraging is that Liberia and Sierra Leone, two post-conflict countries confronting the challenge of containing Ebola, have escaped the lowest Index category of economically “repressed” nations. Many countries in the region appear to be generating the sort of “escape velocity” needed to make the additional institutional changes critical to long-term economic development.

Nonetheless, the region as a whole continues to underperform when it comes to following through on reforms that will help the emergence of a more dynamic private sector and result in more broad-based growth. More critically, the continuing existence in some countries of uneven economic playing fields, exacerbated by weak rule of law, means residents who lack connections are still being left out and have only limited prospects for a brighter future. Vibrant economic growth and lasting development in sub-Saharan Africa depend greatly on increasing the competitiveness of African entrepreneurs—especially in the small and medium enterprise sector—through expanded economic freedom.

In light of Africa’s dynamic and shifting economic growth patterns, Washington should seize the opportunity to reinforce its vision of economic freedom and empowerment through policy actions such as those outlined below.

Prioritizing the Fight Against Corruption

In 2015 sub-Saharan Africa continues to be the second-fastest-growing region in the world, despite the drop in global oil prices that affected several oil exporting countries including Angola and Nigeria. Kenya and Ethiopia, for example, are projected to grow by 6 percent to 7 percent over the next two years. Nevertheless, most African countries still suffer from endemic corruption, fragile protection of property rights, and inefficient entrepreneurial environments. If African countries are to harness the high economic growth rates (currently spurred by commodity exports) to ensure long-term sustainable growth, their governments (and the U.S.) should prioritize anti-corruption and transparency measures.

Africa is a diverse continent with varying challenges and opportunities. In the “freedom from corruption” indicator of the Index, the divergence in individual country scores could not be more apparent, with scores ranging from Botswana at 64.0 (of 100) to Somalia’s meager score of 8.0. Corruption scandals continue to plague the continent.

Action Needed. African governments must continue the fight against endemic corruption and enhance the rule of law at all levels of government. In addition, African governments need to adopt policies and practices that build trust and accountability with their citizenry and improve the overall investment climate to ensure economic freedom for ordinary citizens.

U.S. Policy Recommendation. Despite progress, lingering corruption continues to cripple sub-Saharan Africa’s growth potential and undermine opportunities for U.S. investors throughout the continent. Strong rule of law is a critically important factor in attracting dynamic flows of global investment capital. Development-assistance capacity-building programs cannot succeed without an increased focus by African governments on these transparency and anti-corruption efforts.

The U.S. government should prioritize the accountability of national and local governments, for example, by making future funding of U.S. foreign aid programs for them contingent on their making steady improvements in rule of law. The U.S. government should also place a stronger emphasis on working directly with civil societies in African countries by empowering nongovernmental voluntary groups to serve as watchdogs for corrupt government practices and individuals. These watchdog groups would be aided by a more focused approach by the U.S. on building e-government capacity in African countries.

Encouraging African Economic Integration

Africa—the least economically integrated region in the world—faces major economic and governance challenges as it seeks a macroeconomic growth agenda capable of integrating the entire continent into the global economy. More than a decade ago, former United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan observed that open markets are the only realistic way to pull hundreds of millions of people in developing countries out of abject poverty. However, Africa has yet to harness the power of market-oriented growth. Formal intra-African trade remains at a dismal level, the lowest of any region in the world. In order to maximize the region’s trading potential, a serious and bold plan for greater continent-wide integration needs to be developed and put into action.

Action Needed. During the 2015 World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, several African politicians and business leaders pledged to remove all of the impediments to intra-Africa trade. These words, however, have not been supported by concrete actions beyond the few continent-wide initiatives already underway. In an effort to establish a Continental Free Trade Area (CFTA) by 2017, the African Union is pursuing greater African market integration. The CFTA is also working to, by 2028, integrate the Regional Economic Communities into a single customs union with a common currency, central bank, and parliament. Nevertheless, complex customs unions, administrative procedures, and burdensome regulations continue to hinder CFTA negotiations.

U.S. Policy Recommendation. With improved policy environments and a rich natural resource endowment, many economies on the African continent have become more attractive trade and investment partners to the rest of the world. The U.S. should no longer regard African countries primarily through the assistance lens, but increasingly as viable economic trading partners.

The U.S. has taken some limited steps to develop a strategic market-access approach to Africa. In 2000 Congress passed the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), a trade-preference program aimed at promoting growth by reducing U.S. barriers (tariffs, for instance) to African exports. The legislation was extended twice, in 2005 and 2010, and is due to expire again in September 2015. More than 30 sub-Saharan African countries benefit from AGOA membership. Trade between Africa and the U.S. has more than tripled since AGOA’s enactment in 2000, and U.S. direct investment in Africa has grown nearly sixfold.

The U.S. should not only renew AGOA through 2025, but also use the legislation to spur African economic integration (via the CFTA) and ultimately transform the trade-preference program into an FTA between the U.S. and the entire region. Given its critical linkage to AGOA and U.S. market access, Congress should also renew and reform the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP), the U.S. trade program designed to promote trade with developing countries. The goal of AGOA should be to push African progress toward integration and greater economic freedom.

Encouraging More Robust Investment Flows

Continued economic growth and expansion of freedom in sub-Saharan Africa will require inbound investment. In Africa, mobile telephone technology is exploding, discoveries in natural resources continue, and 60 percent of the world’s uncultivated arable land remains on the continent—some of it deemed off-limits by various governmental decisions. Foreign direct investment (FDI) in 2013 grew by 16.2 percent to $43 billion (from $32 billion in 2012). Meanwhile Africa’s middle class is growing—it is already collectively larger than India’s, and, by 2020, 50 percent of households will have discretionary spending power.

Yet FDI in sub-Saharan Africa has been hindered by political unrest and economic uncertainties. Investors’ concerns over taxation issues and the absence of specific investment protections, particularly for U.S. investors, means much of the positive changes occurring on the continent remain unrealized by U.S. investors.

In the summer of 2014, President Obama hosted the inaugural U.S.–Africa Leaders’ Summit, which included a day-long event focused primarily on private-sector development in Africa, yet a significant gap remains between vision and action. Countries such as China play by different rules; their opaque investments in extractive industries may help build a port, a highway, or a railroad in Africa today, but they carry with them a potentially bitter legacy of corruption and nepotism.

Action Needed. In order to spur international trade and economic growth, sub-Saharan Africa needs sound domestic policies that will increase foreign investment. Free, transparent, and open investment regimes provide maximum entrepreneurial opportunities and incentives, while expanding economic activity, greater productivity, and job creation. Intra-regional and global trade in Africa will require serious investments in infrastructure. To attract more foreign direct investment for such projects, African governments need to create effective investment frameworks—characterized by transparency and equity—and support investments from all firms—not just those that are large or politically well connected.

Cabo Verde is one such sub-Saharan African country making significant improvements to its investment climate, and is subsequently attracting foreign and indigenous investment in both the technological and tourism sectors. Its economy might be small in comparison to regional giants such as Nigeria, but a number of other African governments, mainly those of other Lusophone countries, have taken notice of the speed at which Cabo Verde implemented market-oriented reforms.

U.S. Policy Recommendation. Thriving market-based private-sector actors are key to achieving inclusive and broad-based economic growth because they aggressively seek out opportunities for trade, investment, and partnership. The U.S. government should refocus its development policy on trade and investment with sub-Saharan African countries and prioritize the vigorous pursuit of an expanded commercial agenda—for instance, by establishing a broader network of BITs, and negotiating double-taxation treaties (DTTs) that remove fiscal burdens from investment-oriented capital flows. These concrete actions would advance the discussion beyond the simplistic message “Trade, not Aid.”

Negotiating a greater number of U.S. BITs and DTTs with African governments, would be a catalyst for U.S. investment in some of the fastest growing economies in the world. Among sub-Saharan African countries, only South Africa currently has a DTT with the United States, and only six sub-Saharan African countries (Cameroon, Congo Brazzaville, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Mozambique, Rwanda, and Senegal) have signed BITs. The U.S. should focus on expanding the number of such agreements under the auspices of the Trade and Investment Framework that the U.S. and the East African Community (EAC) agreed upon earlier this year. Given its early development of an AGOA-country strategy and a maturing synthetic-textile-manufacturing industry, Kenya, an EAC anchor country, should be a top priority.

Additionally, Congress should avoid enacting federal securities laws to advance social or political goals in Africa. Under Section 1502 of the Dodd–Frank Act, countries registered with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) operating in the DRC and neighboring countries are subject to enhanced regulatory scrutiny to combat “conflict minerals”—raw materials that finance armed violence. The problem is serious, but rather than helping, the clumsy and expensive regulations of Dodd–Frank are forcing the closure of artisanal mines and pushing former miners into dangerous militias. Compliance requirements have forced U.S. investors to seek opportunities elsewhere and harmed economic freedom in central Africa.

Strengthening Protection of Property Rights

Secure property rights give citizens the confidence to engage in entrepreneurial activity, save their income, pledge collateral for loans and mortgages, and make long-term economic plans. Conversely, the lack of property rights is a significant challenge to economic growth—an issue currently undermining sub-Saharan Africa’s economic growth and innovation.

In sub-Saharan Africa, the historical obstacles to protecting property rights and threats to economic freedom range from traditions of tribal and communal ownership and land holdings to restrictions based on race (South Africa’s former apartheid system) to experiments with expropriation and uncompensated redistribution (Zimbabwe under President Robert Mugabe), and failed collectivization schemes under communist and socialist economic models.

Furthermore, African governments still lack effective and independent judiciaries capable of protecting property rights and enforcing contracts because they remain susceptible to corruption and political maneuvering.

Another major hindrance to economic development stems from the weakness and under-development of government administrative institutions and their inability to provide formal property titles and documentation proving ownership of land holdings, a situation that creates legal insecurity and economic vulnerability—especially for small and medium enterprises. The average regional Index of Economic Freedom property rights score is weakest in sub-Saharan Africa and is second only to Freedom from Corruption as the lowest indicator in the Index for the region. This highlights the fact that, overall, weak rule of law in Africa remains the largest challenge to improving region-wide economic freedom.

For example, the use of the state’s expropriation power remains on the South African government’s official policy agenda; current legislation threatens to re-open the land claims process. These actions would be detrimental to both domestic and foreign private property owners.

Action Needed. Sub-Saharan African nations must pass and enforce laws to expand the coverage of and provide documentation for private property holdings. In some countries only a small percentage of land is covered by the property cadaster.

U.S. Policy Recommendation. The U.S. should continue to work with international and regional institutions, such as the International Finance Corporation (IFC) of the World Bank, international development assistance cooperative partners from other Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, and the African Development Bank, to prioritize capacity-building programs that establish and enhance judicial institutions and the protection of property rights. For example, the U.S. should strengthen the existing initiatives to provide technical assistance to sub-Saharan African countries with regards to developing appropriate legal norms and land-titling processes.

North America

Ryan Olson

The North American region (home to the three NAFTA partners—the United States, Canada, and Mexico) has long benefited from its relative openness to international trade and investment. Although it enjoys the highest level of economic freedom of any region in the world, those levels have fallen in recent years. However, political changes in Mexico have raised hopes for improvements in economic freedom and, in the United States, a reversal in government spending relative to the size of the economy advanced economic freedom slightly in 2015. North America continues to score above the world average in eight areas of economic freedom. It has high levels of business freedom, trade freedom, monetary freedom, and labor freedom. High government spending in the United States and Canada drags down the region’s performance, and Mexico needs to improve its property rights protection and ability to fight corruption. Mexico lags significantly behind its two northern neighbors in these two areas, and long-term reform is critical to advancing economic development.

Building Regional Economic Integration

The North American Free Trade Agreement remains the centerpiece of an increasingly interconnected North American marketplace in goods, services, and capital. Since its inception in 1994, NAFTA has helped to create an integrated marketplace of over 475 million people producing about one-third of total world gross domestic product (GDP). NAFTA has helped increase income levels, employment, investment, and trade.

While improvements under NAFTA have been beneficial to all parties, there is still a significant amount of work to do to maximize its impact. All three governments continue to make progress on increasing economic openness and removing barriers to trade. One of the largest such efforts is the “Beyond the Borders Action Plan,” an initiative between the U.S. and Canadian governments designed to eliminate cross-border trade barriers. These reforms include accelerating customs procedures, eliminating duplicative screening, and implementing new technologies to ease cross-border shipments.

For example, the action plan aims to help trusted businesses and travelers move efficiently across the border by strengthening “trusted trader” and “trusted traveler” programs and eliminating supply chain bottlenecks. Similarly, the plan also calls for both countries to speed clearance for cargo through new pre-screening and pre-clearance procedures. These efforts are to include: offering a “single window” for importers to submit information required by various government agencies electronically, expediting clearance for low-value shipments, facilitating trade by improving transparency and accountability for border fees, and improving infrastructure at border crossings.

In 2014 U.S. Customs and Border Protection followed up this commitment by beginning an 18-month pilot of the “trusted trader” program, a move that could set the stage for full implementation. In addition, the second phase of a pre-inspection pilot program began. This program allows CBP officers to conduct customs inspections on the Canadian side of the border, facilitating quicker processing through the U.S.–Canada border.

Trade-enhancing improvements have not been limited to the United States and Canada. In January 2015, at the conclusion of a second, three-year pilot program, the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) approved a plan to allow Mexican long-haul trucks to operate in the United States. Previously, Mexican trucks were confined to a 25-mile radius from the border, meaning that many goods had to be warehoused and transferred to U.S. trucks to continue their shipment, a lengthy and costly process. Now, Mexican trucks that comply with safety and training standards will be allowed to proceed to any destination in the contiguous United States, allowing goods to be shipped directly from Mexican suppliers to U.S. businesses and consumers at lower cost.

Implementation of this program is long overdue. Under NAFTA, the original intent was for Mexican trucks to have unfettered access to U.S. highways by the year 2000. However, domestic interests, including U.S. trucking unions, prevented those rules from being implemented, and spurred nearly $2 billion in retaliatory tariffs by Mexico against the U.S. Nearly two-thirds of bilateral U.S.–Mexico trade occurs via land shipments, so full Mexican access to U.S. highways will reduce costs and inefficiencies, producing savings that will eventually be passed on to U.S. consumers.

Recent improvements in North American trade freedom have not been limited to more efficient continental transactions. In October 2014, for example, the Canadian government and the European Commission signed a preliminary text of a new Canada–EU trade pact—the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement. If ratified, the agreement could remove duties on 99 percent of goods, open up public procurement markets, and strengthen investor rights, including through greater use of arbitration panels.

Notwithstanding the success of NAFTA and various efforts to facilitate trade between its member countries, barriers still remain. Particularly in the U.S., recent events have highlighted continued market access issues for Canadian companies. For example, “Buy America” provisions in U.S. Department of Transportation funding recently precipitated a hold on construction of improvements to the Alaskan Marine Highway’s only Canadian port at Prince Rupert. The Canadian government put the hold on the American-leased port’s upgrade because U.S. federal funding for the project requires the use of American-made iron and steel, which the Canadian government and local contractors oppose. Furthermore, in June 2014, the Canadian government filed an intervention with the WTO’s Government Procurement Committee to “register concern” and seek clarification from the Obama Administration of all federal and state “Buy America” provisions passed since 2013. “Buy America” provisions raise costs for government procurement and make U.S. companies vulnerable to the possibility of retaliatory tariffs. These events, along with continued delay of the Keystone XL pipeline and disputes over the construction of a customs plaza at the New International Trade Crossing in Detroit, have raised bilateral trade tensions between the U.S. and Canada.

To combat these and other remaining trade barriers, all three countries are participating in TPP talks, which, if successful, could further liberalize trade. In addition, Canada and Mexico each have unilaterally reduced tariffs in order to boost their international competitiveness.

Action Needed. Political leaders need to push back against parochial special interest groups that fear increased competition. These groups’ concerns must not be allowed to obscure the overall benefits of NAFTA’s trade liberalization. All countries should work—through the TPP and bilaterally—to remove barriers to international trade and investment, and the U.S. and Canada should work to make permanent the pilot programs begun under the “Beyond the Border” Action Plan to facilitate trade. In addition, all three countries should work to avoid and resolve the petty trade disputes that have cropped up in recent years. Disputes over “Buy American” provisions, funding for customs terminals, and oil pipelines only undermine the long- and well-established trade ties of the North American region.

U.S. Policy Recommendation. Congress should roll back “Buy America” provisions that stifle cross-border procurement markets. “Buy America” provisions raise the threat of retaliatory tariffs on U.S. businesses, undermine U.S.–Canadian infrastructure upgrades, and distract from efforts at further cross-border trade liberalization.

Mexico: Still Behind Its North American Neighbors, but Catching Up

Promoting economic freedom in Mexico is key to addressing joint economic, security, and civil society concerns. In December 2012, Enrique Peña Nieto began his single six-year term as president of Mexico. Since taking office, Peña Nieto has taken many positive steps to challenge the private and public monopolies and duopolies that have dominated and hampered huge portions of Mexico’s economy.

These combines—in energy, telecommunications, construction, food production, broadcasting, financial services, and transportation—have long been a drag on competitiveness and job creation. Notwithstanding Mexico’s NAFTA membership, these sectors were effectively “roped off” to benefit politically powerful rent-seekers—a phenomenon known as “state corporatism.” This had the same practical effect as that of traditional protectionist trade barriers. Despite being the third-largest oil producer in the hemisphere and the 10th-largest in the world, Mexico’s oil industry has been in decline.

Since 2012, Mexico’s government has taken huge steps to address these issues. After pushing through constitutional amendments on telecommunications and energy sector reform early in his term, President Peña Nieto took the final step in 2014 by signing the new regulatory structures into law. In the telecommunications sector, new rules will have the effect of breaking the monopoly in Mexico over mobile and fixed line telecommunications currently held by billionaire Carlos Slim’s America Movil. These reforms should help open up the Mexican telecommunications sector to increased competition and investment. Reports by the Mexican Federal Communications Institute indicate that overall telecommunications and cell phone services prices have already dropped by over 15 percent since February 2013. Meanwhile, more consumers can now access open-air broadcast television channels.

Historic energy reforms, kicked off by additional constitutional changes in 2013, were also signed into law in 2014. Before these new constitutional changes, PEMEX, the state-owned oil company, held an unchallengeable monopoly on oil production in Mexico. Now, according to a 2014 report by The Heritage Foundation, foreign companies may be able to invest in Mexico’s vast offshore reserves through production and profit-sharing contracts, service contracts, and licenses. It is estimated that production and efficiencies will increase as foreign companies bring in new technologies that PEMEX could not previously develop. Other Mexican reforms that advanced in 2014 include breaking the monopoly on the energy-distribution sector, which was previously controlled by a federal commission. Since electricity rates in Mexico are nearly double those of the United States, some observers hope this could realize significant savings for Mexican producers and consumers.

While President Peña Nieto has received significant praise for ushering through these historic reforms, some have criticized him for ignoring a deteriorating rule of law and security situation. Over the past year, several high-profile executions and kidnappings have again brought the nation’s attention back to drug-related violence, and reminded Mexicans that economic reforms must be coupled with improvements in the rule of law.

In September 2014, 43 students from a local teaching college in the town of Iguala in the state of Guerrero went missing. The subsequent discovery that the mayor of Iguala had participated in their abduction and had been complicit with drug gangs in the region touched off a national uproar. Although Mexico’s Freedom from Corruption score improved in the 2015 Index of Economic Freedom, these events are a tragic reminder of the continued need for high-priority focus on improvements to rule of law and security in Mexico.

Action Needed. Mexico should continue to liberalize and open its economy. Recent reforms in the labor and energy markets have been major steps in the right direction. In the energy sector further reforms are needed to remove barriers to foreign investment, simplify the regulatory structure, and remove PEMEX’s remaining monopolistic power. If these reforms result in a flood of new private investment they will create hundreds of thousands of new jobs that will encourage even more would-be economic migrants to remain at home in Mexico. Continued economic reform must be accompanied by a reaffirmed government commitment to the rule of law. Corruption is still prevalent in many levels of the bureaucracy, and Mexico’s infamous clientelist and corporatist tendencies persist. Furthermore, ongoing crime and violence undermine the business environment and threaten the country’s most marginalized citizens.

U.S. Policy Recommendation. Congress should take steps to remove the U.S. crude oil export ban, an archaic law that limits the exports of unrefined oil products. Removing the crude oil export ban would help to make PEMEX more competitive, giving it the opportunity to acquire different fuel blends that would help diversify its product base. In the short term, the U.S. Department of Commerce should immediately approve a crude oil swap permit filed in 2013 by PEMEX. This permit would authorize the purchase of 100,000 barrels of lighter U.S. crude that its PEMEX could use to refine more profitable diesel and gasoline blends.

Asia–Pacific

William T. Wilson, PhD, and Luke Coffey

The Most Improved Region—Again

According to the 2015 Index of Economic Freedom, for the second year in a row, the 43 countries encompassing the Asia–Pacific region have outperformed the world’s other regions in terms of advancing economic freedom. The Asia–Pacific region continues to have, by far, the largest number of the world’s “free” economies.

The region, however, also continues to be distinguished by enormous disparities in this freedom. In the 2015 Index, the scores of 27 countries have improved; 14 have worsened. Of those that improved, seven countries, including Taiwan, Vietnam, and Laos, achieved their highest-ever economic freedom score. Four countries (Taiwan, South Korea, the Philippines, and Burma) have now achieved five consecutive years of advancing economic freedom.

The Asia–Pacific region ranks above the world average in fiscal freedom, government spending, and labor freedom. Yet, the region does poorly overall in property rights, freedom from corruption, and financial and investment freedom.

While four of the world’s freest economies—Hong Kong, Singapore, Australia, and New Zealand—are in this region, many of the other Asia–Pacific countries remain “mostly unfree.” North Korea, which continues to reject any form of free-market activity, remains the world’s least free economy.

Leading the world in three of the 10 economic freedom categories, Hong Kong once again is the world’s freest economy. Runner-up Singapore is beginning to close the gap with Hong Kong as a more dynamic and competitive financial sector emerges in the city-state. Australia and New Zealand continue to set the standard for clean, corruption-free government, and benefit significantly from their transparent and efficient business environments and open-market policies.

India and China are still “mostly unfree.” Despite high economic growth rates, these nations’ foundation for long-term economic development continues to be fragile in the absence of effectively functioning legal frameworks. Progress with market-oriented reforms has been uneven and has often backtracked at the urging of those with a political interest in maintaining the status quo. In Central Asia, Kazakhstan’s links to the Russian economy are hampering its growth.

In 2014, the focal points for Asia’s economic freedom agenda were financial liberalization, auditing and reporting standards, and privatization. This year, the global agenda will focus on the growth in domestic credit and the TPP, and will examine evidence of progress in privatization throughout the region.

The Asian Credit Bubble

Credit growth continues to accelerate throughout the region. For Asia, total debt (household, corporate, government) reached a new high in 2014, reaching a record 210 percent of GDP. That is up a startling 50 percentage points since 2008.

Bank credit, as a share of Asian GDP (excluding Japan), bottomed-out at 80 percent of GDP in 2002–2003, but then quickly climbed to 108 percent in 2013 (latest year available). It is now higher than in 1997, the year the devastating Asian financial crisis commenced.

Much of the rise in debt is corporate. While companies in the West have been deleveraging since the 2008 financial crisis, Asian companies have been doing the opposite. In fact, corporate Asia now has the world’s most leveraged balance sheets. According to Standard & Poor’s, corporate debt in Asia will exceed that of North America and Europe combined by 2016.

Action Needed. Asia’s financial institutions should increase capital adequacy ratios to reduce the threat of increased defaults. More importantly, they should begin a process of deleveraging, with aggregate credit growing more slowly than nominal GDP.

U.S. Policy Recommendation. The U.S. should encourage Asian nations to adopt Basel III standards. The accord is a voluntary regulatory standard on bank-capital adequacy, stress testing, and market-liquidity risk.

Progress on the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP)

The TPP is a large trade deal (the biggest in two decades) between 12 countries around the Pacific Rim. It is expected to reduce tariff and non-tariff barriers on goods and services and liberalize all sorts of regulations. The countries included in the agreement are some of the largest and fastest growing partners of the U.S. The 12 countries in the agreement account for 40 percent of world GDP and over one-quarter of world trade. The treaty is reported to have 29 chapters, dealing with everything from financial services to agricultural trade. The current agreement does not include China.

The TPP is part of the U.S.’s broader historical commitment to engagement in Asia. It is similar to other recent trade deals, such as the U.S.–Korea Free Trade Agreement (KORUS), in that it includes a broad range of regulatory and legal issues.

Action Needed. As of the date of this writing, while there apparently has been progress made, there remain a number of critical sticking points obstructing a TPP. These include: protection of intellectual property rights (the U.S. has been pushing for stronger copyright protection for music and film); state-owned enterprises (many TPP governments, such as Vietnam, Singapore, and Malaysia, have major state-owned or “linked” sectors); and Japanese protectionism in its agricultural and auto sectors. The U.S. maintains a 25 percent tariff rate on the import of light trucks.

U.S. Policy Recommendation. U.S. negotiators should press hard for the greatest possible freedom to trade in finalizing the TPP.

Financial Liberalization

One of the most pressing and critical issues currently facing the emerging economies of Asia is the continued development of their financial sectors. The banking sector dominates the emerging markets’ financial intermediation throughout Asia, but many are state-owned and allocate capital poorly. Many of Asia’s emerging stock markets, if they exist, are essentially illiquid. (Only five emerging Asian economies had active stock markets in 2014.) Corporate bond markets are also nonexistent in most emerging economies, and many emerging-market consumers have no access to credit.

Regrettably, the global financial crisis has led to a sweeping re-evaluation of financial market regulation. Basel III, for example, which mandates significantly higher capital and liquidity requirements for banks, was largely designed for Western institutions. Scheduled to be implemented by 2018, the accord ignores the fact that emerging economies are in earlier stages of economic and financial development and, therefore, will require different regulatory regimes as they deepen their financial markets and democratize credit.

Action Needed. Although financial laissez-faire economics is dead in Asia, at least for the foreseeable future, countries should nevertheless implement financial-sector reforms that lead to greater financial freedom, and in turn, financial development.

U.S. Policy Recommendation. The U.S. should encourage countries with relatively closed financial systems to open them up to foreign competition. Heavy-handed banking and financial regulation by the state—regulation that exceeds the traditional state responsibility to maintain transparency and honesty in financial markets—will impede efficiency and should be removed over time in developed and developing Asian countries alike.

Kazakhstan’s Links to Russian Economy Are Hampering Its Growth

2014 was a tough year for the Kazakh economy—the largest economy in Central Asia. Although the economy is not in recession, growth has been slower than expected. In addition to the economic impact of low oil prices, there has also been a negative trickle-down effect from Western economic sanctions on Russia. As the Russian ruble has weakened, so, too, has the Kazakh tenge. In 2014, the Kazakh central bank devalued the tenge by 19 percent; further devaluations in 2015 cannot be ruled out. The Eurasian Economic Union, to which Kazakhstan belongs, came into force in January 2015 and continues to hamper Kazakhstan’s already sluggish economic growth prospects.

Perhaps the biggest shock to the Kazakh economy has been the drop in the price of oil. Over the years, Kazakhstan enjoyed an economic prosperity based mostly on exploitation of its abundant mineral wealth—primarily hydrocarbons, but also uranium and ferrous and nonferrous metals. Devaluation of the tenge was expected to drive labor costs down and boost the natural-resources sector but, due to the drop in oil prices, that has not happened. Making a bad situation worse, the Kashagan oil field—one of the largest-ever oil discoveries—is still not in production, as development costs are billions of dollars in the red and the project will be delayed for several years since it can be profitable only at an oil price of $100 per barrel.

Action Needed. The Kazakh government should develop policies encouraging diversification of the economy into the agriculture, manufacturing, and services sectors. Furthermore, Astana should extract itself from Russian-dominated organizations such as the Eurasian Economic Union.

U.S. Policy Recommendation. Kazakhstan and the entire Central Asia region are strategically poised for economic growth, since the Chinese and East Asian markets, to which they supply raw materials, are expanding. U.S. businesses should take advantage of opportunities in Kazakhstan—as Russia and China are already doing. The U.S. can also help Eurasian countries to deal with challenges in education, health, and environment, as well as the security threat posed by terrorism. Kazakhstan aspires to join the WTO, and the U.S. can assist Kazakhstan to make the adjustments necessary to do so. One of those steps would be to pull away from Russia’s Eurasian Economic Union—a retrograde structure that serves only the interests of Russia.

The Middle East and North Africa

James Phillips

Many of the countries in the Middle East and North Africa have undergone political and economic upheavals during the protests of the “Arab Spring.” But long-overdue economic reforms continue to be neglected or postponed due to political instability. As a result, the gradual rise in economic freedom that had been recorded in recent years has come to a halt. Structural and institutional problems abound, and the regional unemployment rate is among the highest in the world. Such high unemployment rates, which are most pronounced among younger members of the workforce, have, in turn, boosted political discontent, undermined many governments, and cast a long shadow on the region’s economic prospects.

The region’s problems are complex and rooted in decades of authoritarian rule, which has kept power and resources in the hands of a few. Simply holding elections or allowing freedom of expression will not solve these problems. Indeed, elections merely amplify political cleavages if there is no consensus on the rules of the game after the elections. Stable democracies require a supportive civil society, independent judiciary, respect for the rule of law, limited government, freedom of the press, religious freedom, and a decentralization of power. But as long as national economies are dominated by the state sector, political leaders will be reluctant to share power if that diminishes their access to state-controlled wealth. Difficult institutional reforms are required to reduce the state’s role in the economy and in peoples’ lives.

Middle East Dominated by Authoritarian and Corrupt Regimes

Many Middle Eastern countries are dominated by authoritarian regimes that carve out significant portions of national economies for their own benefit or to provide patronage for their supporters.

The tragic human catalyst that ignited the “Arab Spring” was the young Tunisian food vendor Mohammed Bouazizi, who set himself on fire on December 17, 2010, after police confiscated his fruit and vegetable cart and humiliated him, apparently because he refused to pay them a bribe. Many young Tunisians identified with his plight and were inspired to join popular protests that ousted the corrupt authoritarian regime of President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, who fled the country.

Government corruption not only squanders economic resources, but also restricts economic competition and hinders the development of free enterprise. Corruption was a major issue that helped to galvanize opposition to governments in Egypt, Libya, Syria, Tunisia, and Yemen. Entrepreneurs are unlikely to invest their capital or hard work unless they have a reasonable chance to earn a fair return for their efforts, free from the threat of government seizure or the interference of corrupt officials.

Action Needed. Ruling elites need to commit to a philosophy of limited government and the development of independent judiciaries and commercial legal frameworks that protect property rights and ensure free competition.

U.S. Policy Recommendation. The U.S. should strengthen the OECD’s anti-bribery convention to address the sharp challenges in the Middle East. Transparency and anti-corruption practices in trade and investment should be emphasized in bilateral investment treaties and other economic exchanges. Private enterprise, a vital engine of economic growth, cannot flourish unless entrepreneurs are free to expand their businesses without fear of government confiscation.

Socialism Still Widespread in Arab Countries

In the 1950s, many Arab countries adopted socialist models for economic development, which curtailed economic growth, encouraged expansion of bureaucracies, and prompted the creation of inefficient state-owned industries. It is no coincidence that Egypt and Tunisia, the first two countries to experience the “Arab Spring” uprisings, had strong socialist legacies that created corrosive corruption and dysfunctional bureaucracies.

Action Needed. Arab countries need to discard failed socialist ideologies and emphasize market reforms and economic liberalization.

U.S. Policy Recommendation. Washington should encourage Middle East governments to liberalize their economies, remove bureaucratic red tape, and encourage domestic and foreign investment to spur the development of vibrant private sectors. Expensive state-owned enterprises should be privatized wherever possible in a transparent and fair process to guard against crony corporatism. Expanding the private sector will fuel economic growth and help to create a larger middle class—an important building block for developing stable democracies.

Many Middle East Economies Too Small to Stand Alone

Many Middle East economies are too small to provide the range of goods and services that their people demand or need. In particular, many Middle Eastern countries import food, automobiles, machinery, electronic devices, and high technology from outside the region. Consumers would benefit from lower prices for these imported goods, which are sometimes discouraged by protectionist tariffs imposed to prop up uncompetitive local industries.

Action Needed. Trade freedom reflects an economy’s openness to the flow of goods and services from around the world, and a citizen’s ability to interact freely as buyer or seller in the international marketplace. Trade restrictions can manifest themselves in the form of tariffs, export taxes, trade quotas, or outright trade bans. However, trade restrictions also appear in more subtle ways, particularly in the form of regulatory barriers. A reduction of government hindrances to the free flow of foreign commerce would have a direct and positive bearing on the ability of individuals to pursue their economic goals and maximize their productivity and well-being.

U.S. Policy Recommendation. The United States should try to negotiate bilateral FTAs with Middle East countries and encourage the formation of a regional free trade zone. FTAs could not only lower the costs of imported goods and help boost imports from the United States, but also expand exports to the U.S. market. Jordanian exports to the United States, for instance, skyrocketed from $229 million in 2001—when it ratified the FTA with the U.S.—to $1.2 billion in 2013. Although an FTA with Egypt may not be politically viable at the moment, Washington should encourage the expansion of the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Qualifying Industrial Zone (QIZ) program, which allows goods produced jointly by Israel and Egypt to enter the United States duty-free. Such expansion would have the ancillary benefit of encouraging greater cooperation between Egypt and Israel.

Iraq: More Reforms Needed

In addition to political reforms, Iraq needs systematic economic reform to stabilize its political system. The country suffers from high rates of unemployment, heavy subsidies for food, oil, and natural gas products, as well as endemic corruption.

For decades, Iraq’s governments have imposed a wide array of constraints on economic activity. Although sometimes imposed in the name of equality or some other noble societal purpose, such constraints are in reality most often imposed for the benefit of elites or special interests, and they come with a high cost to society as a whole. By substituting political judgments for those of the marketplace, government diverts entrepreneurial resources and energy from productive activities to “rent seeking”—the quest for economically unearned benefits. The result is lower productivity, economic stagnation, and declining prosperity.

Action Needed. The Iraqi government must undertake systematic economic reforms to root out corruption in the swollen public sector, privatize government monopolies wherever possible, reduce government subsidies to consumers, and create stronger and more effective institutions to improve governance. It is particularly important to create a transparent and effective oil sector, which is the driving force of the Iraqi economy. The central government also needs to create a better business environment for foreign investors, and boost exploration and development of Iraq’s huge oil production potential. The December 2014 agreement between the Iraqi government and the Kurdistan Regional Government on oil issues is a significant step forward that should help both sides increase oil production and export revenues.

U.S. Policy Recommendation. The U.S. should encourage the Iraqi government to undertake free-market economic reforms, root out corruption, reduce government subsidies, and create a transparent oil sector. It should also press the Shia-dominated government to reach out to Sunni and Kurdish Iraqi political parties and bring them into the ruling coalition on a long-term basis. This will help reduce ethnic and sectarian tensions, undercut the appeal of the Islamic State (also known as ISIS or ISIL) and other terrorist groups, and help to forge a national consensus that will enhance political stability and enable economic growth.

Central and South America and the Caribbean

Ana Quintana and James M. Roberts

The markets in the countries of Central and South America and the Caribbean total almost half a billion people and account for trillions of dollars in annual trade and investment. Resource-rich countries in the Americas continue to profit from demand for commodities fueled by fast-paced growth in Asia and other markets, which is supporting their sustained economic growth. Millions of Latin Americans have risen from poverty as a result.

In fact, according to the World Bank, extreme poverty in Latin America and the Caribbean has fallen by half in the past 15 years and now the region counts more people in the middle class than in poverty. Its economic freedom scores, according to the 2015 Index of Economic Freedom, range from excellent (Chile) to abysmal (Cuba and Venezuela), with a major player such as Brazil, the world’s sixth-largest economy, registering comparatively low scores because of a penchant for protecting local industries with high import tariffs and regulations, as well as maintaining swollen bureaucracies and a heavy-handed regulatory regime.

This year there are several positive regional trends. Many Latin American countries are emerging as global leaders in free trade. The vast majority of the world’s FTAs are either based in the region or have regional participants. The Alliance of the Pacific (Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru, along with candidate members Costa Rica and Panama) has emerged as a praiseworthy model of regional economic integration that will enhance the prosperity of its member countries. Unprecedented energy reforms in Mexico could create numerous mutually beneficial opportunities for U.S. and other multinational energy companies.

The Future of Communist Cuba

According to the 2015 Index of Economic Freedom, Cuba remains among the world’s least free economies, ranking ahead only of North Korea at the bottom of the list. The Cuban economy continues to suffer the consequences of decades of communist economic policies, cronyism, and mismanagement. Without the support it received over the years from its international benefactors, Cuba’s economy would have long since imploded.

At the height of the West’s Cold War against communism, the Soviet Union subsidized the struggling Castro regime with upwards of $4 billion a year in military and economic support. Given the unsustainable economic model embodied by communism, the decline and fall of the Soviet Union brought extreme economic hardship to Cuba and caused the regime to look elsewhere for the funding without which it would have collapsed. From the late 1990s until 2014, Hugo Chavez’s Venezuela provided that support to the Castro regime through the monetization of about 100,000 barrels of crude oil a day.

In 2015, as falling oil prices pressured the Cuban-supported regime in Caracas, the Castro government once again found itself in desperate need of a new benefactor. Normalization with the United States appeared to be the lifeline that the dying regime needed. Re-opening trade and diplomatic relations with the U.S. will allow Cuba to continue subsidizing a broken and inefficient economy without incentivizing needed reforms. Normalization with the Americans, however, will not spur meaningful economic growth absent those structural reforms.

Potential U.S. investors must be forewarned about the reality of the economic situation in Cuba: As currently constituted, Cuba’s economic and market systems are not ready for an influx of capital or imported goods from the U.S. and other leading economies.

Serious infrastructure deficiencies and flaws in monetary policy mean there will be few opportunities for U.S. companies to enjoy any quick profits from entry into the Cuban market. If anything, Cuba will be a place only for companies with very long-term investment horizons. Decaying supply chain facilities coupled with a massively inefficient and burdensome regulatory bureaucracy will slow the import/export and investment processes. Cuba’s two-tiered monetary system and hard currency controls also limit the quantity of goods and services that Cuban corporations may purchase from U.S. importers using traditional trade financing methods.

Action Needed. The Cuban regime must take significant steps toward market-based democracy.

U.S. Policy Recommendation. The U.S. commercial, economic, and financial embargo against Cuba dates from 1960 and is maintained in force today by means of sections of the following six U.S. statutes: the Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917; the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961; the Cuba Assets Control Regulations of 1963; the Cuban Democracy Act of 1992; the Helms–Burton Act of 1996; and the Trade Sanctions Reform and Export Enhancement Act of 2000. These U.S. laws should not be modified to permit normalized trade and economic relations with Cuba unless and until the Cuban regime takes significant steps to move toward a market-based democracy. The United States government must use the powerful leverage of negotiations for normalization to incentivize democratic and economic reforms on the island and not lift the embargo until Cuba meets the standards for its removal.

Economic and Political Crisis in Venezuela

The foundations of economic freedom in Venezuela have crumbled. As one Latin American pundit put it, “Brazil is becoming Argentina, Argentina is becoming Venezuela, and Venezuela is becoming Zimbabwe.” When the late Hugo Chavez took office in 1999, Venezuela scored 56 of 100 possible points in the Index of Economic Freedom. Today, after more than 15 years of authoritarian populism under Chavez and his successor Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela merits a score of just 34 points. This 22-point plunge is among the most severe ever recorded in the Index’s 21-year history. Venezuela’s 2015 rank—175th of 178 countries—place it among the most repressed nations in the world, above only Zimbabwe, Cuba, and North Korea.

In the past year, the economic and security situation has deteriorated further. Strict hard currency controls and haphazard devaluations have distorted the value of the Venezuelan currency (the Bolivar), which has declined 97 percent in purchasing power in the past three years. The country has incurred significant public debt and has the highest level of inflation in Latin America. Government mismanagement has created extensive scarcities of food and basic goods. Rather than introducing needed structural reforms, the Venezuelan government has turned to rationing, instituted price controls, and seized even more of what relatively few privately held companies still exist.

Action Needed. Regional leaders in Latin America have been reluctant to address the crisis in Venezuela. Their timid pronouncements as members of the leftist, Venezuelan-led “Union of South American States” (UNASUR) multilateral grouping have done little to quell growing domestic unrest in Venezuela. In late 2014 the Obama Administration announced targeted U.S. sanctions against seven specific Venezuelan government officials involved in “violence against anti-government protesters” or the “arrest or prosecution of individuals for their legitimate exercise of free speech.” Without regional support and similarly tough actions against the Maduro regime by neighboring Latin American governments, however, the impact of this unilateral U.S. measure will be limited.

U.S. Policy Recommendation. The U.S. should work to garner support among hemispheric allies against the Venezuelan government’s police-state tactics and active suppression of freedom of political expression. In 2014, at the request of Panama and with support from Canada and the U.S., the Organization of American States convened a special session on Venezuela. Additional such meetings could provide a viable regional platform for dispute resolution, but the U.S. must insist that any future peace discussions be based upon the Inter-American Democratic Charter, adopted on September 11, 2001, and meant to strengthen democratic institutions and improve human rights in the hemisphere. Both the U.S. and Venezuela are signatories to it. The Venezuelan government is thus obligated to guarantee the protection of human rights, including freedom from political persecution. The U.S. government must maintain unceasing pressure on it to do so.

Economic and Security Crisis in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras

The “Northern Triangle” countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras are in the midst of an unprecedented crisis. Rampant corruption and weak state institutions make it almost impossible for their governments to combat threats posed by transnational gangs and organized criminal groups. Exacerbating the problem is the region’s weak economic growth rate. Although poverty rates in Latin America have declined in general, they have increased in Guatemala to 54 percent of the population and remained relatively stagnant in Honduras at a very high 65 percent.

In addition to the dire economic straits, the region is facing a chronic citizen-security crisis. Honduras has the world’s highest homicide rate, averaging 91 per 100,000 citizens. El Salvador is fourth in the world with an average of 41 per 100,000, and Guatemala is fifth at 40 per 100,000. (By comparison, the U.S. average is five per 100,000.) Lying along a critical trafficking route, the Central American isthmus is particularly vulnerable to illicit smuggling. Honduras alone is a layover spot for upwards of 80 percent of northward-bound drug flights.

In early 2014, there was an influx of unlawful migrants on the U.S.’s southwest border, the majority of whom came from the Northern Triangle. Fleeing crime, violence, and lack of economic opportunities, many of the migrants were unaccompanied children. In response, the White House requested from Congress $1 billion for Central American development to: “1) Promote prosperity and regional economic integration; 2) Enhance security; and 3) Promote improved governance.”

Action Needed. Deteriorating conditions in the region will continue to impact U.S. national security. The situation, however, cannot be remedied by simply increasing U.S. foreign assistance. These governments have limited absorptive capacity for development assistance and often lack the political will to make necessary domestic political, fiscal, and anti-corruption reforms.

U.S. Policy Recommendations. From fiscal year (FY) 2008 through FY 2014, U.S. foreign assistance delivered under the Central American Regional Security Initiative (CARSI) to all seven countries in Central America totaled $803 million—a figure that does not include two Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) compacts with El Salvador totaling $365 million. It should be noted that El Salvador is currently the only MCC recipient in Latin America, in spite of the fact that the ruling socialist party’s economic and social policies directly contradict the MCC’s core values. In response to the 2014 border crisis, the Northern Triangle countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras have entered into a development and security plan (the “Plan of the Alliance for Prosperity in the Northern Triangle”) which has been strongly endorsed by the Obama White House. Rather than standing up an entirely new program—one that fails to emphasize sufficient accountability, financial participation, and ownership of outcomes on the part of the aid-recipient countries—the U.S. instead should work to improve the existing CARSI program. In developing policy considerations to promote security in the Western Hemisphere, the U.S. should be wary of promoting potentially ineffective assistance programs—clearly defined outcomes that promote U.S. national security must be the cornerstone of any policy. Any American taxpayer funds should directly target improvements to the rule of law and be conditioned on recipient governments making internal structural reforms.

Europe

Ted R. Bromund, PhD, and Luke Coffey

In recent years, there has been a significant realignment of European countries in terms of their economic freedom. For example, in the 2015 Index, 13 European countries recorded their highest economic freedom scores. Nine of the world’s top 20 freest economies are in Europe and the region scores well above the world average in eight of the 10 economic freedoms, leading the world in investment freedom and monetary freedom. On the other hand, Europe was also one of the two regions in the world—along with North America—that experienced a drop in economic freedom in 2014, a year when it lost its leadership in trade freedom.