About the Authors

Ariel Cohen, PhD, is a Visiting Fellow in the Douglas and Sarah Allison Center for Foreign and National Security Policy, of the Kathryn and Shelby Cullom Davis Institute for National Security and Foreign Policy, at The Heritage Foundation. Ivan Benovic, an MA graduate from the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies and a BA graduate from the Moscow State Institute of International Relations, was a member of The Heritage Foundation’s Young Leaders Program during the fall of 2013. James M. Roberts is Research Fellow for Economic Freedom and Growth in the Center for Trade and Economics, of the Institute for Economic Freedom and Opportunity, at The Heritage Foundation. The authors thank Sergey Alexashenko, former first vice chairman of the Russian Central Bank, and Maria Snegovaya, PhD, of Columbia University, for their

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s seizure of Crimea and continuing aggression in the eastern oblasts of neighboring Ukraine, a dangerous political-military action without precedent in Europe’s post–World War II history, and the Putin government’s consistent policy of increasing state economic control (statism or “etatism”), can best be understood in this context: Putin and his inner circle may well be leading Russia on the path to stagnation and economic decline. The only way such a regime can survive is to grab more territory through imperial aggrandizement while distracting its citizens through ultra-nationalist propaganda that celebrates Putin as Russia’s savior. This path seems politically unfeasible, with dire economic consequences for the country, the investors, and its people at large.

Western sanctions targeting Russia’s financial, energy, and military sectors in response to the winter 2014 invasion and annexation of Crimea, the shooting down in July of a Malaysian Airlines plane with the loss of 298 lives, and Putin’s ongoing aggression in eastern Ukraine have already cost Russia tens of billions of dollars. Even some of the sanctions Russia imposed in retaliation for Western sanctions have backfired. They are inflationary and will hurt Russia itself far more than the West.

The price tag of the military occupation of Eastern Ukraine may be even higher: Its industrial base is obsolete; the workforce lacks skills necessary in the modern economy; and the demographics are declining due to age and migration.

The economic drag of the Ukrainian adventure, with a price tag that is impossible to calculate, will further burden the Russian state budget, already over-reliant on hydrocarbon revenue. According to Russia’s Ministry of Finance, Russia needed an average oil price of just $50 to $55 per barrel to balance the budget in 2008. By 2012, that minimum had increased to $117.[1]

Russia has already tapped into its national pension fund to increase pensions in Crimea and will further tap into the sovereign wealth funds to the tune of over $3.6 billion to finance its investments in the occupied peninsula.[2] However, the greater damage will occur as a result of massive capital flight, warns Alexei Kudrin, the former deputy prime minister and long-serving finance minister. In the first half of 2014, capital flight amounted to nearly $70 billion, and is projected to reach $160 billion by the end of the year.[3] The ruble has depreciated more than 12 percent since the beginning of the year and is continuing to slide.[4] Russia will also suffer from a brain drain as the government cracks down on the remaining independent media and promulgates draconian laws on freedom of expression.

This Special Report will demonstrate that, in addition to the high cost of foreign policy adventurism, Russia also suffers from indigenous structural economic discrepancies, which make its elites richer, the rest of the population poorer, and the economy less competitive. With the ongoing hostilities against Ukraine, the Russian economic prognosis has only gotten worse.

Russia’s Self-Imposed Problems

More than two decades after the collapse of Communism, Russia’s economy suffers from systemic problems that hinder its future. These are failures of governance, macroeconomic mismanagement (over-valuation of the ruble, bad private-sector debt, and unpaid bank loans), and poor economic decision making and business culture.

In particular, over-centralization, the bureaucratic chokehold over the economy, and corruption are preventing Russia from becoming a fully developed country. Overdependence on natural resources exports, the failure of the rule of law, including deterioration and collapse of the legal system, and insufficient property protection are only a part of the problem. The other problem cluster includes widespread corruption; massive and inefficient bureaucracy; low rates of citizen participation in the local, regional, and federal levels of government; and an intentional destruction of nascent democratic institutions, such as the Duma, by the executive power.

The lack of economic opportunity and social mobility have destroyed hope in the country’s future and driven many of the educated and entrepreneurial younger Russians to emigrate to achieve success. This, in turn, has hindered investment in the Russian economy, incentivized capital flight, aggravated the brain drain, and strengthened Russia’s authoritarian regime.

Solving these issues would require a change of heart both at the highest levels of Russian society and government as well as among ordinary people. If these problems are not tackled in the near future, Russia risks becoming a corrupt police state with even higher dependence on exports of raw materials that have a well-established history of price volatility, with negative economic and social consequences for its long-term future.

It does not have to be this way. Russia has demonstrated considerable achievements: Its per capita income rose from $1,775 in 2000 to $14,818 in 2013, making it a high-income country. It has many investment opportunities not just in natural resources, but also in housing, infrastructure (which badly needs upgrading), health care, and education, to mention just a few. It is the largest car market in Europe and boasts a highly educated population with a 100 percent literacy rate.

After the breakup of the Soviet Union and the fall of Communism in the early 1990s, Russia embarked on a path toward a free-market economy. It managed to abandon quickly (and traumatically) its centrally planned economic system, but was never able to fully transform itself into a modern free-market economy.

Under President Boris Yeltsin, the Russian government privatized state-owned companies in exchange for vouchers representing tiny fractional shares in those state companies; sold them to workers; or outright auctioned off many state-owned enterprises (SOEs), including in the lucrative oil sector. Yeltsin’s team of young economic reformers imposed sweeping structural reforms throughout the economy. This was a deep and radical change, warts and all.

However, Yeltsin did not introduce similar reforms to Russia’s governmental institutions. He permitted elements of law enforcement and the secret police (FSB) to become further corrupt and, in many cases, merge with organized crime. As Anders Aslund, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, has noted in his great study of that period, Yeltsin’s failure to force both economic and political reforms when he had the power and public support right after the breakup of the Soviet Union was his biggest mistake.[5] Privatization in Russia benefited a relatively small circle of people, and to a great extent failed to create a propertied middle class. This had tragic consequences for Russia as well as other former Soviet states.

Since becoming prime minister in 1999 (after Chechen militants invaded neighboring Dagestan and created a public safety crisis) and then succeeding Yeltsin as president in 2000, Vladimir Putin has reversed many of the political reforms implemented by his predecessor,[6] including election of single-mandate representatives in the state Duma, election of governors, and relative freedom of expression on state-controlled TV channels.

Besides leading the country away from democracy and back to authoritarianism, Putin did not change a massively corrupt economic system that is based on bribery and personal connections. This is a system in which free enterprises and entrepreneurs face serious obstacles if they do not have the necessary ties in the government or are not backed by the siloviki (“men of power”) who control the military, police, and intelligence services. Thus, Russia’s most valuable assets came to be controlled by a small group of oligarch businessmen. Putin permitted them to keep their wealth in exchange for political loyalty. Aslund has compared the power of these oligarchs—most of whom became wealthy through control of companies in the energy sector—to 19th-century American “robber barons.” This oligarchy has become Russia’s biggest obstacle to economic development. To solve that problem, Aslund recommends that the oligarchs be required to “pay a compensation for benefits they have enjoyed, in return guaranteeing them their property rights.”[7]

In fact, according to a 2013 report by the investment bank Credit Suisse, a “staggering 35 percent of household wealth in Russia is owned by just 110 people, the highest level of inequality in the world.”[8] Because of this deep inequality, many Russians are disillusioned in the capitalist model and are supportive of political parties, such as Communists and the militant socialists of the “new left,” who advocate wealth redistribution.

Absent reforms, Russia’s economy under Putin will remain stunted by mismanagement, corruption, abysmal rule of law, poor protection of property rights, and crumbling infrastructure. Likewise, just as those Soviet-era Communist dictators who preceded him clung to their absolute power, Putin has little choice but to continue to pursue an irredentist and expansionary agenda in order to impose economic and political mechanisms (such as the Eurasian Union) that will force Russia’s neighbors to subsidize its failing economy. To shore up political support at home for his foreign adventurism, Putin has skillfully pandered to his fellow citizens’ long-standing inferiority complex vis-à-vis the West by stoking Russian nationalism.

The Russian Economy and the Resource Curse

How It Works in Theory. The Russian federal budget has become increasingly dependent on the exportation of natural resources. The Russian Ministry of Finance estimates that in 2014 over 50 percent of budget revenues will come from energy export tariffs, including combined export tariffs and a natural resource extraction tax.[9] Conventional resource curse theory, as formulated more than a decade ago by Richard Auty, Jeffrey Sachs, and other economists, would predict that, in comparison with resource-poor countries, countries with abundant natural resources, such as oil and gas, will suffer from lower long-term economic growth, higher corruption, poorer human rights records, more internal social tensions, lower government accountability, and lower international competitiveness of their economies.[10]

More recent research, however, suggests that the true nature of the causality outlined above may be just the reverse. Christa Brunnschweiler and Erwin Bulte from the Center of Economic Research in Zurich argue that it is, in fact, the bad institutions that hinder development of the economy and leave the country dependent on the exportation of natural resources.[11]

Another study, conducted by Sarah Brooks and Marcus Kurtz from The Ohio State University in 2012, concluded that there is no “resource curse” in Russia (or any other country) per se.[12] They treat the phenomenon as an economic, not a political, issue. Moreover, Brooks and Kurtz argue that the mere presence of oil and other natural resources may not in itself mean that the country is doomed by definition not to be suitable for democracy. Rather, the outcome—whether a country becomes democratic, and to what extent—depends more on the political regimes of that country’s geographical neighbors than on its natural resource endowment. These studies have important implications for Russia and its economy. They suggest that Russia’s natural resource richness cannot be used as an excuse for its poor state of institutions, and also that, regardless of the export structure, there is a compelling reason to reform the country’s economy.

How It Works in Practice. Some Russian economists and policymakers seem to understand the need to improve the fundamental conditions for the private sector in order to restart growth. The government has even adopted several federal programs aimed at doing so.

For instance, a government program called Economic Development and Innovation Economy foresees the investment by the state of about $26 billion in seven years (2013–2020) to implement measures aimed at developing a favorable business environment for small and medium enterprises (SMEs), increasing the innovative activity of the private sector, and improving the efficiency of government management.[13] The goal is to improve Russia’s rating in the World Bank’s annual Doing Business report, as well as to increase the share of the workforce working in SMEs, improve people’s satisfaction with federal and local government services, and increase the share of cutting edge firms that innovate.

The baseline is quite low: Russia is ranked 92nd of 189 countries in the 2014 edition of Doing Business.[14] The most problematic areas include “dealing with construction permits” (178th) and “trading across borders” (157th). More significantly, the share of gross domestic product (GDP) spent by either the private sector or the government on research and development in Russia in 2011 was only 1.12 percent, significantly below developed Western European countries such as Germany (2.3 percent) or the U.S. (2.7 percent). According to the World Bank’s Worldwide Government Indicators, in 2012 Russia ranked in the bottom quartile in terms of rule of law and in the bottom 16 percent in terms of control of corruption.[15]

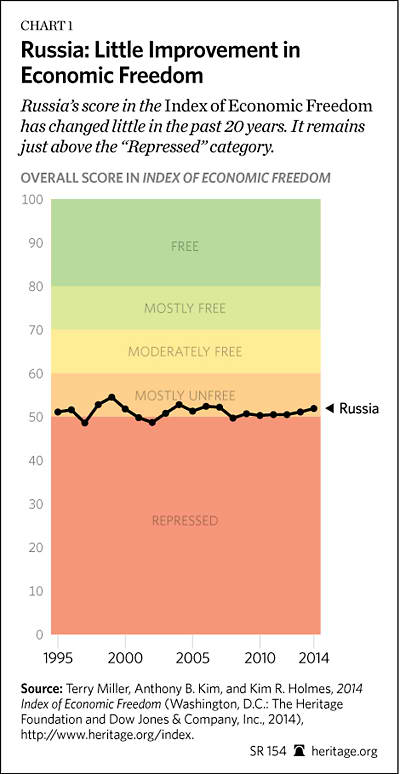

Russia’s performance on the 2014 Index of Economic Freedom,[16] published by The Heritage Foundation and The Wall Street Journal, is equally dismal. Russia’s economic freedom score is 51.9, making its economy the 140th freest of 178 countries ranked and “Mostly Unfree.” Although its score reflected a modest improvement (in control of government spending), that was counterbalanced by declines in trade freedom, freedom from corruption, and fiscal freedom. Russia is ranked 41st of 43 countries in the Europe region, and its overall score is below the world average. Only countries with an overall score of 60 or more are considered even “Moderately Free.”

Over the 20-year history of the Index, Russia’s economic freedom has been stagnant, with its score improving less than one point. Overall, notable improvements in trade freedom and monetary freedom have been largely offset by substantial declines in investment freedom, financial freedom, business freedom, and property rights, and Russia’s economy remains “Mostly Unfree.”

The Index further finds that Russia’s foundations for sustainable economic development remain fragile, exacerbated by the poor legal framework. Corruption, endemic throughout the economy, is becoming ever more debilitating. The state maintains an extensive presence in many sectors through state-owned enterprises.

Russian State-Led Modernization Has Not Succeeded—Nor Will It

As the late Harvard University professor David Landes noted in his monumental study on The Wealth and Poverty of Nations, Russia has been pursuing “state-driven development” since the 16th century in an effort to “catch up with the West by adoption of Western ways.”[17]

As of June 2013, the Russians were still seeking to modernize. That is when President Putin outlined a government strategy aimed at reforming the Russian economy.[18] The strategy consisted of a series of lofty-sounding policy goals:

- Prevent capital drain, by concluding bilateral agreements with tax-haven countries for the purpose of deeper sharing of tax-related information (similar to the U.S. agreements under the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, but without sanctions for non-cooperative banks).

- Create tax incentives for long-term individual investments, incentivizing investment in the capital market. Existing investments in the Russian Far East already receive a special boost of a zero tax rate for 10 years; other tax breaks have been adopted for businesses that are considering investments in the Far East.[19]

- Pass a law against illegal financial operations to combat money laundering. The law would obligate banks and other financial organizations to disclose their clients’ account data to tax authorities, which will give these authorities easier access to bank secrets.

- Increase the accessibility of loans. The measures are to include improved refinancing mechanisms, developing competition in the banking sector by removing excess oversight procedures, and expanding government guarantees for SMEs.

- Ensure a reliable protection of property rights for the clients of financial and insurance companies.

- The All-Russia People’s Front, the pro-Putin political organization, should ensure sufficient public oversight of the procurement procedures of the government and SOEs—a constant source of corruption allegations.[20]

- Strengthen the state’s regulatory role in SOEs, including the use of personnel changes to increase economic efficiency.

- Create a system of government guarantees of pension funds, which will help remove restrictions on investing in long-term projects.

Other modernization efforts in recent years include the announcement in December 2012 of a Russian federal government program of state financing[21] to boost the competitiveness of the Russian industry. That program, adopted on April 15, 2014, envisions its initial development using government financing. The levels of subsidies are to be gradually decreased in order to ensure the industry’s adaptation to the world market.[22]

The goal is to promote the technological development of domestic industry by incentivizing resource-efficient and environmentally friendly technologies, which would ensure production of competitive, state-of-the-art goods and services. The government believes that it is necessary not only to stimulate developing basic infrastructure, such as roads and railways, but also to become involved in more advanced industrial sectors in order to boost innovation in high-tech areas. In other words, they advocate an industrial policy whereby the government “picks winners and losers,” something that a long and sorry history in many countries has shown is best left to private venture capital.[23] The fact that the Putin administration is pursuing this program, however, suggests that the statist view of how best to innovate and encourage more competitive firms is in the ascendancy. To wit, Putin’s allies, such as presidential economic advisor Sergey Glazyev, and vice premier in charge of the military-industrial complex Dmitry Rogozin, talk about cutting economic ties with the West and increasing state involvement in the economy. Notwithstanding the failures of such policies around the globe, the industrial “white elephants” are in evidence from Brazil to India.

Besides government interference, Russian industry continues to suffer from other systemic problems that are hindering its transition to innovation-based growth. These include poor intellectual property protection; structural distortions; significant aging of the main capital stock; low adoption rates of innovations; and technological lags in a range of sectors, such as in the solid-state electronics,[24] automotive,[25] and communications sectors.[26] Low labor productivity, high costs for raw materials, energy-insensitive production methods, shortage of state-of-the-art production equipment, an insufficient share of production with high value added, insufficient human capital, and insufficient access to financial resources are rampant.[27]

Bitter Reality Belies Statist Rhetoric. Although the ambitious government programs described above seem to be aimed at the core of the current Russian problems, their potential effectiveness is likely to be undermined by a lack of readiness and political will of the presidency to adopt serious measures to fight corruption and improve the government’s accountability procedures.

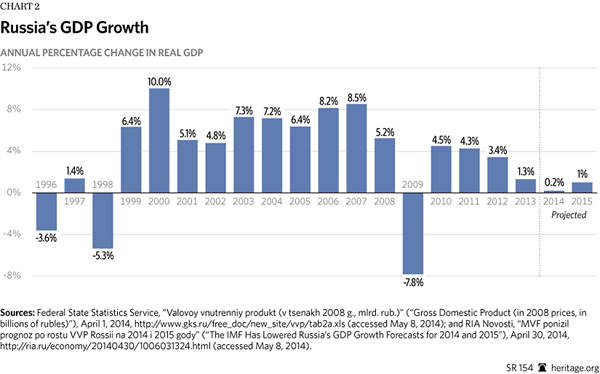

In 2013, the Russian economy grew 1.3 percent,[28] which is considerably lower than prior to the 2008–2009 crises (around 7 percent). The 2014 GDP growth rate is likely to be negative. The structure of foreign trade continues to remain basically unchanged and does not reflect the modernization rhetoric of the Russian government. According to Russian customs statistics, 73 percent of Russia’s exports outside the Former Soviet Union (FSU) in 2012 were energy, primarily hydrocarbons, and raw materials, while within the FSU the corresponding share was 55.4 percent.[29] These figures have been fairly stable over the past several years.[30] An analysis of them demonstrates that for the past decade, Russia has been unable to construct an internationally competitive economy and continues to be mainly a resource exporter.

Share of SMEs in GDP. According to Andrey Belousov, economic advisor to Putin and the Russian Federation’s former minister of economic development, one-quarter of Russia’s labor force (17 million people) either work for SMEs or are the sole proprietors.[31] These 17 million people currently produce only around 19 percent of Russian GDP, whereas the corresponding GDP share in developed countries is between 40 percent and 50 percent of GDP. Other Russian sources estimate the SME share of GDP to be anywhere between 15 percent and 25 percent.[32]

High Taxes for SMEs. Russia has an extraordinarily high tax rate for SMEs. In 2011, Russia increased the payroll tax rate on SMEs from 20 percent to 34 percent.[33] According to Boris Titov, President Putin’s “ombudsman for the rights of businessmen,” such a high rate has a detrimental effect on Russian SMEs and blocks their development. The high taxes encourage small businessmen to pay salaries in cash, in violation of the law.[34] Another problem is the lack of a qualified work force. According to the 2012 report by the government-supported Opora Rossii (“Pillar of Russia”—the Russian Public Organization of Small and Medium Businesses), 47 percent of respondents faced severe or considerable difficulties finding qualified workers for positions they were trying to fill. In addition, 38 percent of respondents considered it difficult or impossible to get even a short-term loan. The difficulty in borrowing is even greater with longer-term loans. More than 70 percent of business leaders complained about the presence of administrative barriers to SMEs in their regions.

The Ministry of Economic Development estimates that roughly another 25 percent of Russia’s labor force (roughly 18 million people) are trapped in Russia’s grey and black economies. These informal workers are producing about the same contribution to GDP as the SME sector—many working in small but unlicensed businesses—but they do not receive the same level of benefits or income for their efforts.[35] Thus, the overall share of SMEs in the Russian economy (and the increased tax collections by the government that they would generate) could be significantly higher.

In fact, it is the government itself that is one of the main drivers of the massive and growing underground economy in Russia. High interest rates, taxes, insurance and licensing fees, as well as demand for “social protection payments” by the police (and the Russian secret services) compel many businesses to operate illegally. In early 2013, the number of SMEs was in decline due to these increasing social payments. Thus, the government’s goal of increasing the GDP share of SMEs to between 60 percent and 70 percent seems unrealistic. To do so, the Russian economy would have to liberalize to become more even more dynamic and investor-friendly than those of developed Western economies—not a likely scenario.

The probability of that liberalization, then, is very low, given the high levels of bureaucratic intervention in the Russian economy and, especially, the weakness of the rule of law in Russia as reflected in the 2014 Index of Economic Freedom. Russia’s scores on “Business Freedom” and “Rule of Law” are among the lowest in Europe.

The Rule of Law Deficit. Since Putin pulled the country away from the reforms of the early Yeltsin era, economic growth in Russia has been noteworthy for occurring in an atmosphere increasingly marred by corruption, cronyism, and the whims of bureaucrats. International governmental and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have documented the deterioration of the rule of law in Russia—and have been targeted by the Putin regime with smears and Soviet-style propaganda.

On June 13, 2013, the European Parliament adopted a resolution calling on Russia to respect the human rights of its citizens, expressing concern about the ongoing, systematic, and severe violation of individual rights. The European Parliament is also concerned about the pressure on Western-funded pro-democracy NGOs operating in Russia, politically motivated trials, lack of political and media freedoms, and weak rule of law.[36]

Freedom House is concerned about the damage that NGOs are forced to sustain by labeling their publications as produced by “foreign agents,” as required by Russian law.[37] Transparency International is concerned about the selective nature of the Russian judicial system, as the cases of Mikhail Khodorkovsky, Alexei Navalny, Pussy Riot, and the 2012 Bolotnaya Square protests have demonstrated. As Transparency International reported in 2013, “A compromised justice system, one that is used for political purposes, seriously damages the rule of law and also diminishes a state’s ability to fight corruption.”[38]

Corruption: Russia’s Deadliest Disease. Corruption continues to be one of the principal factors hindering the development of SMEs in Russia. Corruption is the reason for the bankruptcy or closure of one of every seven businesses in the country.[39] Many international analysts believe that surveys concerning corruption are skewed positive, presenting a rosier picture than the reality. Even these positively skewed results are a reason for grave concern. In general, corruption is often perceived by businessmen as a cost of doing business.[40]

Twenty percent of respondents who took part in an annual SME survey conducted in 2012 by Opora Rossii said that it is extremely difficult or impossible to start a business in the country. More than 40 percent said it is “considerably difficult”; more than a quarter expect demands for bribes when undergoing government audits for health, fire, and tax compliance, or to receive a new installation for electrical service; and nearly a third of business owners consider corruption payments to be the norm for government contracts. Fifteen percent of business owners reported the need to offer bribes during court proceedings.[41] All of these statistics came from a Russian government survey, so the true level of corruption in Russia must be far higher.

No Substantial Efforts by the Government to Fight Corruption. Instead, the government undertakes populist measures that look attractive on the surface, but do not address the core of the problem. For instance, in May 2013, President Putin signed a law that banned government employees and their immediate relatives from having bank accounts in foreign banks or possessing foreign financial instruments.[42] This was a step to increase state control over the elites in public service and deny free-thinking “system liberals” (reformists) sources of income outside the country. Second, the law would prevent public scandals connected to government officials’ foreign holdings.[43] This was followed by a bill to forbid officials from holding foreign securities. The hope was not only to improve the deplorable image of the Russian bureaucracy in the eyes of the society, but also to stimulate investment in the domestic economy. Nevertheless, Anatoly Aksakov, former member of the Duma, admits that the law could be circumvented.[44] One way to do it is through offshore companies. Another way is to transfer the property and cash in their foreign accounts to their adult children, which is not forbidden by the law. Thus, the law seems to be a public relations charade meant for public consumption. It is unlikely to have a real effect. In practice, the law will affect only lower-level bureaucrats who lack political pull, believes Alexey Makarkin, a political scientist.[45]

Over the years there have been several notable corruption scandals leading to widely publicized prosecutions that have resonated both in Russia and abroad, such as the most well-known cases of Alexey Navalny and Mikhail Khodorkovsky—both enemies of Putin. These are politically motivated cases, but they reflect the general sorry state of the judiciary in Russia and the ease with which opponents of the Putin regime can be prosecuted and sentenced notwithstanding their wealth, popularity, or international stature.

Alexey Navalny received a five-year sentence and a $15,000 fine for allegedly embezzling 16 million rubles (around $500,000), although similar sentences are given for economic crimes of a much larger scope.[46] Careful reading of the case, however, suggests that he was innocent. The appellate court suspended the sentence, which allowed Navalny to run (unsuccessfully) for mayor of Moscow. In the future, however, Navalny will be barred from running for office since he is now a convicted felon. Meanwhile, he faces new charges that carry a 10-year maximum sentence.

Similarly, Mikhail Khodorkovsky’s second prison term was about to end in August 2014, before he was pardoned by Putin on December 20, 2013—presumably in an attempt to weaken international criticism of Russia’s human rights violations before the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi.

Khodorkovsky’s prosecution reminds the business community that anyone in Russia can be sentenced, fined, or imprisoned, no matter how powerful—or innocent—he is. The situation concerning Khodorkovsky only further adds to the low confidence of Russian businessmen in the system. Although the Russian Ministry of Economic Development said that Khodorkovsky’s pardon would positively influence Russia’s investment climate,[47] some experts, such as Alexander Shokhin, head of the Russian Union of Industries and Entrepreneurs, and economist Vladimir Tikhomirov, do not share the ministry’s optimism.[48]

Expropriations by Force—Case Studies in Corruption. The most egregious violations of property rights are expropriations of successful businesses of different sizes. The most notorious ones include the expropriation of the YUKOS oil company, founded by Mikhail Khodorkovsky. Most of its assets, worth more than $40 billion before the beginning of its nationalization in 2003, eventually ended up under the control of the state oil company Rosneft for a fraction of their market value. Khodorkovsky was arrested in 2003 and spent 10 years in jail after two trials that most legal experts considered to be “kangaroo courts.” Putin released him from jail just before Christmas in December 2013 on humanitarian grounds. Khodorkovsky then went into exile in Germany.[49]

Another noteworthy example is that of the Yevroset cell-phone retail chain, founded by Yevgeny Chichvarkin. In late 2008, he was accused of extortion and kidnapping, and had to flee to London. His deputy, Boris Levin, spent two years in custody before his own legal case was closed. In the meantime, Chichvarkin sold Yevroset to Aleksandr Mamut (the 45th richest man in Russia in 2013 with an estimated fortune of $2.3 billion)[50] for $350 million—an artificially low price reflecting the pending criminal charges against Chichvarkin.[51] He is still afraid to come back to Russia and lives in London.[52]

The case of Mikhail Gutseriev did not go quite according to plan for the Putin regime. The initial scheme, similar to that of Yevroset, was to acquire the oil company RussNeft (not to be confused with the state-owned Rosneft) that was founded by Gutseriev in 2002. The Russian government accused him of tax evasion and illegal entrepreneurship. Gutseriev was forced to flee Russia in 2007, but returned after the criminal case against him was closed two and a half years later. He successfully reacquired all shares of RussNeft and is now its sole owner. His success came at a price, however, as the process of reconsolidating RussNeft assets cost him almost $2 billion.[53]

In November 2007, Oleg Shvartzman, a Russian oligarch, explained in an infamous interview how the Russian state consolidates the country’s assets under the control of large holding companies owned by either the state or by individuals with close ties to the highest levels in the government.[54] He stated that it is de facto state policy to artificially minimize the market value of their target enterprises and then pressure the management to sell them at those lowered prices. The cheaply sold enterprises then end up under control of companies owned by family members and close confidants of Russia’s high-ranking officials. This is the key flaw in the system of economic control that exists today in Russia. This flaw applies not only to large businesses, but to SMEs as well.

Capital Flight. The miserable investment and business conditions in Russia under the Putin regime have a longer-term cost. Capital continues to flee the country. In 2011, the overall number reached $80.5 billion, although in 2012 the number declined to $56.8 billion.[55] In 2014, the capital flight may be significantly higher than during the past several years as a result of Putin’s annexation of Crimea. Putin’s lack of respect for international law (although it is Russia that keeps calling on other countries to unconditionally follow international norms), together with the looming threat of more tangible economic sanctions, further undermines the trust of international investors in the Russian economy. Alexey Ulyukayev, Russia’s Minister of Economic Development, said that economic growth in the first quarter of 2014 was 0.8 percent, not the expected 2.5 percent.[56] He admitted that this year’s economic situation is expected to be the worst since the 2008–2009 economic crisis.

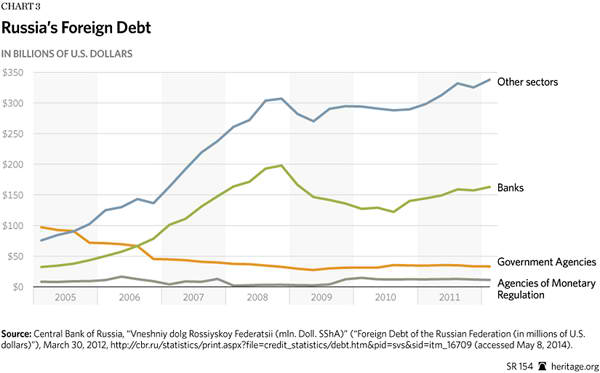

According to the Central Bank of Russia, in 2013 capital flight reached $59.7 billion.[57] In the first quarter (Q1) 2014, capital flight reached $50 billion, and Alexei Kudrin has projected it to reach $160 billion for the year.[58] Some experts argue that some portion of this figure includes funds spent abroad by Russian companies to acquire foreign assets. Nevertheless, the Central Bank admits that large capital flight from Russia has resulted from the unfavorable business environment. Capital flight is compounded by the growing foreign debt. (See Chart 3.) While Russia is still in better condition than the U.S. and many Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development countries regarding overall public and private debt obligations, the trend of rising debt accumulation is unmistakable, with bond rates beginning to rise in 2014, and larger interest payments. Russian foreign debt grew rapidly: over 20 percent year on year in 2013, stable in Q1 2014, and projected to reach $801 billion in 2014.[59]

The Ukrainian crisis has dramatically accelerated the negative debt and currency dynamics. The Central Bank of Russia will be forced to spend heavily just to support the ruble and prevent it from crashing, while the investment flight will accelerate. Thus, foreign loans will become even more expensive and less accessible, and will result in continuous decline of Russia’s capital markets.

Putin’s Adventurism Abroad and Crackdown at Home Harm Investment Climate

Foreign Investment. At first glance, the data on foreign direct investment (FDI) in Russia look impressive. The amount of FDI in the Russian economy rose rapidly from less than $5 billion in 2001 to $75 billion in 2008. In 2007, Russia became one of the top 10 worldwide destinations for FDI.[60] However, a significant part of the FDI comes from the Bahamas, the British Virgin Islands, Luxembourg, or Cyprus. These four destinations accounted for 34.5 percent of Russia’s FDI in 2012.[61] It is thus highly likely that much of the FDI is actually investment from Russian businesses that keep their funds in offshore tax havens to avoid taxation by the Russian government.

Many potential foreign investors are concerned about the poor protection of private property and high levels of corruption. Although the low ranking in terms of investment climate may be somewhat biased downward due to the heavy restrictions in “strategic” areas, such as energy, mining, defense or the aerospace industry, the government itself admits that property rights reforms are necessary to attract more FDI.

Special Economic Zones. In order to stimulate the flow of FDI into the country, the Russian government in 2005 created 24 “special economic zones,” adding four more zones to the list over the following years, bringing the total number to 28.[62] Special economic zones are areas that offer tax benefits for companies that decide to invest there. The flagship of these was supposed to be Skolkovo. Skolkovo, a high-tech park in a Moscow suburb, was established in order to stimulate modernization of the Russian economy through a partnership of government-funded programs and private enterprises, which would receive tax breaks. However, a wave of corruption scandals involving Skolkovo officials soon discredited the entire project.[63] These scandals also constituted a political campaign by the siloviki against Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev and the businessmen who supported him. Even with strong political support, Skolkovo was problematic: Foreign investors, attracted by the favorable tax conditions, were concerned about the lack of legal and policy predictability as well as the lack of property rights protection. Scientists were reluctant to join due to fears of intellectual property rights infringement. In the end, political struggles brought Skolkovo down.

In August 2012, Russia became a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO). Sergey Guriyev, former rector of the New Economic School in Moscow (and currently in exile in France) believes that, in order to take full advantage of the possibilities a membership in the WTO provides, Russia must improve its business climate.[64] Membership in the WTO provides enormous opportunities for SMEs, which are more nimble at adapting to changing conditions and increased competition than large SOEs. Sadly, in Russia the reality is that the old Soviet-era SOEs and the “company towns” they support around the country are likely to face WTO challenges and worsened economic performance with trade liberalization. Those company towns hope that SMEs can fill the vacuum left after closing down or right-sizing the inefficient state-owned giants, but, for the reasons outlined above, the Russian SME sector is unlikely to ride to their rescue.

Bad Governance. Leonid Grigoryev, a leading Russian economist and chair in World Economy at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, is critical of the government plans and rather pessimistic of the country’s future if it does not conduct fundamental reforms. He believes that Russia’s deepest problems include poor governance, a bloated and inefficient workforce, rampant corruption, authoritarianism, weak civil society, increasing bureaucratization of the economy, and a general tightening of laws against private businesses.[65] In his words, “[T]he current government economic programs are not programs aimed at transforming the economy, but rather compilations of current ministerial tasks and work plans.” That sounds like the Soviet-era five-year plans.

The fundamental obstruction to stable economic growth in Russia since the collapse of Communism (and in many respects, since the 1917 Russian Revolution) is the abysmal rule of law. In order to mitigate high-risk operations in Russia, businesses there set aside a portion of their income and invest it (or hide it) abroad. This capital flow from Russia leads to an imbalance between savings and investment, which in turn contributes to reduced availability of credit and, as a result, higher interest rates, which slow growth.

The state fails to take measures necessary to convince Russia’s businessmen to invest their income in Russia. The financial sector continues to be weak, and even large banks have trouble financing important projects. Banks are risk averse, homegrown Russian venture and high-risk capital is scarce and, even if available, is invested abroad. For instance, Alisher Usmanov, the richest man in Russia, invested in Facebook pre-IPO and later sold his share, pocketing around $2 billion.[66] As a result, investment is low and innovations are not taking place as rapidly as they could. The situation is particularly worrisome in manufacturing, including civilian aerospace and biotechnology.

It is hard to know whether Russia wants to appropriate assets in Eastern Ukraine mainly because of economic reasons. However, Ukraine’s industry sector is concentrated in the eastern part of the country, where most of Ukraine’s steel production and arms manufacturing takes place.[67] Also, Ukraine is the fourth-largest arms exporter in the world.[68] The auto and aerospace industries are concentrated there as well. Russia buys most of the motors and engines for its military helicopters and naval ships from Ukraine.[69]

In addition to the lack of venture-capital-funded start-ups in Russia, state corporations and oligarchic monopolists buy (or aspire to buy) SMEs, and also larger privately owned companies, in order to consolidate the market under their control and prevent any serious competition. This further decreases the flexibility of the market, hinders competition, and prevents reforms and growth. For instance, the state-owned Rosneft oil company attempted to diversify into the fertilizer sector and acquire the share of Suleyman Kerimov (21.75 percent) in Uralkali in a nasty corporate-raiding battle.[70] Such a policy seems to be in line with the worldview of Putin’s statist economic advisor, Sergey Glazyev.

Glazyev—a “Bolshevik nationalist” economist and Putin confidant who combines “radical nationalism with nostalgia for Bolshevism”[71] advocates state capitalism, re-nationalization, concentration of enterprises, and militarization of the economy as a means of its modernization.[72] He is also an imperialist who promotes Russia’s territorial aggrandizement through the Eurasian Union, of which Ukraine is obviously the centerpiece.[73]

This “Bolshevik nationalist” strategy clearly skips over problems, such as the poor management of Russian state-owned corporations in general and giants such as Gazprom in particular.[74] Gazprom’s role in Russian foreign policy as a tool to project Russian influence abroad prevents it from being an effective enterprise and maximizing profits. This model harkens back to the “extensive” economy practiced in the USSR. In contrast to a knowledge-based “intensive” economy, which produces growth based on innovation and optimization of production, extensive economic growth takes place through expansion and resource extraction.

Andrey Illarionov, Putin’s former economic advisor, considers Russian economic growth during the Putin years to be unique in the sense that it has occurred in an environment lacking political freedom.[75] According to him, many economists originally thought that political freedom, the rule of law, and absence of corruption are necessary components to ensure sustainable growth. However, historical experience of the countries of the Former Soviet Union shows that these preconditions may not be as necessary all the time.

That being said, the current situation in many sectors of the economy shows that this may be true up to a point. That point, wherever it was, clearly has been passed. Russia now has reached a stage where good institutions do seem to be necessary to ensure further growth. Anders Aslund argues that slowing domestic demand and supply are the main reason for Russia’s declining economic growth.[76] Domestic competition is in decline mainly due to the worsening business climate.

Bureaucrats are keen on preserving the status quo, as it allows them to continue extracting their “rent” from the private sector in exchange for turning a blind eye to violations of laws and regulations purposefully written to be violated.

Institutions Matter—Small Chance for Improvement

Unfortunately, fundamental changes in Russia’s institutions are unlikely in the near future. Even before the crisis, Yevsey Gurvich of the Economic Expert Group estimated the likelihood of such changes at 15 to 20 percent in the case of rising real oil prices, and 30 to 35 percent in the case of declining oil prices. However, now their probability is close to nil. Leonid Grigoryev excludes the possibility of oil prices falling below $80 per barrel in the near and medium-term future,[77] which is unlikely to be low enough to sufficiently stimulate institutional changes. The most likely economic growth rate for Russia in 2014 is around 0.2 percent (predicted by the International Monetary Fund), much lower than last year’s World Bank forecast of 3.1 percent.[78] According to the government, the Russian economy will not generate sufficient revenues to finance the complex set of reforms that are needed.[79]

Russia’s future economic growth will greatly depend on the quality of its state and societal institutions, and they will require funding. If they are not fully funded due to budget shortfalls, social tensions will increase and frictions might escalate between regions that are budget donors (taxpayers) and regions that are federal-subsidy recipients.

For example, the North Caucasus republics are among the most heavily subsidized, with Chechnya receiving 90 percent of its budget from the federal government. Street demonstrations in Moscow regularly feature calls to stop subsidizing the Caucasus. Last year, Prime Minister Medvedev and Finance Minister Anton Siluanov criticized these republics for high spending on their bulging bureaucracies, and failure to meet many of the region’s development goals.[80] This adds to the dissatisfaction of the majority of Russians, who are opposed to subsidizing Chechnya and would rather see that money used in other regions.[81]

Gurvich also mentions insufficient protection of private property, excessive size of the public sector in the economy, and overregulation as fundamental problems.[82] He points out that the relationship between the government and the business elite needs to be fundamentally changed in order for a genuine reform to take place. However, such a reform seems unlikely to happen due to the institutional resistance at the highest level of national leadership, as well as contradictory interests of the Russian elite. On the one hand, the elites are interested in economic growth, but on the other, doing so might help their competitors and undermine their own powerful positions and the continuing prospects of maximizing their wealth at the expense of the rest of the country.[83]

Brain Drain: A Symptom of Economic Deterioration

The unfavorable situation in the economy for would-be upwardly mobile entrepreneurs signals more stagnation and brain drain. The bleak prospects for the young, educated classes in Russia motivate them to export themselves, their skills, and their talent, usually to Western Europe and North America.

The Russian higher-education system is in great need of improvement, too. No Russian universities are counted among the world’s top 100. With several notable exceptions (such as the Bauman and Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology engineering schools, Moscow State University, and the Higher School of Economics), the quality of education at Russian universities is not high enough to prepare an internationally competitive and innovative workforce. Widespread plagiarism and cheating undermine the foundations of what used to be an outstanding education system that prepared top world scientists and engineers during the Soviet era. Due to the prevalence of Communist ideology, however, the Soviet system has irreversibly destroyed social sciences, economics, management, and even genetics.

The lack of competition, the lack of world-class faculty, widespread grade “purchasing” (faculty bribery),[84] cheating, and plagiarism, in addition to the low practical value of many classes, seem to be the most acute problems of the Russian academy.[85] Currently, the culture of cheating and plagiarism at Russian universities teaches students to look for ways to circumvent regulations and take advantage of imperfect control mechanisms at the expense of those who follow the rules.[86]

Thus, human capital in Russia is deteriorating for three reasons: (1) very few possibilities within Russia to obtain a globally competitive higher education; (2) corruption, nepotism, and social stagnation that slow down social mobility and cause emigration of many of those who are fortunate enough to graduate from top schools; and (3) incessant state propaganda, which denies an adequate and realistic perception of political and economic reality.

Although the number of people emigrating each year has fallen significantly from a decade ago, the emigration trend is continuing. In 2011, at least 33,000 Russians emigrated,[87] while in 2013, fewer than 30,000 left the country, according to the official figures.[88] The real numbers may be higher as many do not officially register their emigration. This is compared to over 200,000 per year in late 1990s. Although among the emigrants the share of people with higher education is three times as high as that in the general population, the number appears small compared to the population of 143 million. The Putin government seems not to care. It appears that the government prefers to keep the emigration valve open, as it allows the political troublemakers to leave the country.

Nevertheless, the above-mentioned numbers do not tell the entire story. One reason for the reduced numbers of emigrants from Russia is likely the fact that the European Union and the United States have tightened their immigration procedures and do not allow as many people to immigrate as in the past. Also, due to the current unfavorable economic situation and relatively high unemployment in the West, it is more difficult for foreign nationals to get hired and thus legally immigrate into these countries. In other words, the “supply” for emigration from Russia is intact; it is the “demand” (opportunities in the EU and the Anglosphere) that is lacking. Of those who either have already emigrated or are planning to do so, a majority are engineers, IT specialists, or other science majors.

The interest in emigration among young educated Russians is underscored by public opinion polling in Russia:

- 37 percent of Russian middle-class parents wish their children to permanently live abroad.[89]

- 22 percent of Russian citizens consider moving abroad (and 9 percent consider it on a daily basis).[90]

- According to a survey conducted in summer 2013, 45 percent of Russian college and university students would like to immigrate permanently to a country outside the former USSR.[91]

Moreover, a significant share of the children of the elite already live in the West permanently, which leads to further discontent among ordinary Russians about the hypocrisy of the pseudo-patriotic brainwashing and the lack of genuine patriotism among the elite in the Putin era. In short, educated Russians—people who could drive innovations and modernize the Russian economy—are already either abroad or otherwise at least partially prevented from engaging in economically productive activities.

Naturally, the question arises as to whether immigration to Russia from other states of the former Soviet Union and other countries can make up for the existing brain drain that has happened so far. In a word, the answer is “no.” The vast majority of today’s immigrants in Russia come from Ukraine and Central Asia. These countries suffer from an even worse quality of education than Russia. Thus, the effect of immigration on Russia’s overall educational level is negative, though many of the up-and-coming entrepreneurs in Russia are from the North Caucasus and Central Asia.

Additionally, it is people who lack higher education that most often immigrate to Russia. Younger, educated Russians living in large cities are demanding greater government openness and accountability than rural dwellers because they travel more frequently to advanced economies and learn how things work there. Over the years, the share of blue collar laborers among immigrants from the FSU in Russia has been rising, while their cultural and educational levels are deteriorating.[92]

Exporting Corruption and Bad Governance

The pervasive levels of corruption of the Russian government under Putin transcend its borders. Among the most notorious cases of influential foreign figures alleged to have informal ties to the Kremlin are former German Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder and former Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi. Schroeder is the chairman of Nord Stream AG, a corporation responsible for building and operating the Nord Stream gas pipeline from St. Petersburg directly to Germany. The construction of the pipeline began in the mid-2000s and it went into operation in 2011. Schroeder repeatedly praised Vladimir Putin’s modesty, desire to rebuild Russia, and called him a “flawless democrat.”[93]

Silvio Berlusconi allegedly tried to promote and lobby for the economic interests of Gazprom in Italy. Shortly after Putin’s re-election in 2012, he, Medvedev, and Berlusconi met in Krasnaya Polyana (near Sochi at the Black Sea), reportedly to discuss business affairs.[94] In 2003, Berlusconi was the only Western leader to support the sentencing of Mikhail Khodorkovsky.[95] After that, Berlusconi lobbied the Italian energy company Eni to purchase the confiscated assets previously belonging to YUKOS. The then-president of Eni, Vittorio Mincato, flatly refused to take part in that transaction, as did Eni’s CEO Stefano Cao.[96]

The lack of genuine political freedom not only puts the brakes on economic development in Russia, but also spills over to neighboring countries, including Ukraine, Armenia, Belarus, and Tajikistan, to name just a few. Some Uzbek, Belarusian, and Armenian officials still view Moscow as an administrative model and are studying Putin’s 21st-century repression techniques to gain power for themselves in those countries. Not only is there a lack of pressure throughout the FSU countries from Moscow in cases of violations of human rights and political restrictions, but the Kremlin demands that the neighbors crack down on political freedom and democratic reforms, as it did in Ukraine in 2004 and in 2013–2014.[97]

Sadly, the Russian government does not encourage the governments of the other FSU countries to develop transparency and greater accountability; rather, the opposite. It supports current authoritarian leaders, as Putin sees it as being in Russia’s foreign policy interests to have predictable relations with these countries and avoid models such as the colored revolutions of the past decade in Ukraine and Georgia. These authoritarian regimes are malleable to Russian geopolitical demands, such as membership in the Customs Union, the future Eurasian Union, or deployment of Russian military bases in Armenia, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Ukraine.

The corrupt autocrats, such as Alexander Lukashenko in Belarus or Emomali Rahmon of Tajikistan, can rely on the Kremlin to provide support in case of a threat to their regimes. Thus, Russia is essentially exporting corruption and bad governance to other FSU republics and destroying more open, pluralistic models, such as those of Georgia and Ukraine. That, in turn, breeds more corruption in Russia.

What to Do

Russia must reform itself in four major areas. The first is institutional. Russia desperately needs more effective and transparent institutions. The longer the government hesitates to conduct substantial reforms aimed at improving the Russian people’s confidence in their country and their future, the more difficult it will be to reverse the current negative trends.

The government also needs to launch a systematic anti-corruption campaign, streamline and de-bureaucratize the state administration and the economy, ease overregulation, and limit its interference in the market.

Second, it must protect private property, both physical and intellectual. It must build the court system practically from scratch, purging many abusive and corrupt judges and law enforcement officials. Unfortunately, there is little evidence that such comprehensive reform has either the leadership and support from above or a political demand from below.

The third front is the political system. The ruling United Russia party has become unpopular and fails either to generate new ideas to protect private property, enact reforms, or generate growth. Instead, it is using its overwhelming majority in the Duma to fight foreign-funded NGOs, “gay propaganda,” or adoption of Russian orphans overseas.

It is no accident that the name “Party of Crooks and Thieves,” coined by the anti-corruption crusader, politician, and lawyer Alexei Navalny, became so popular. United Russia needs to compete on a level playing field, not receive privileged treatment through electoral fraud, as its predecessor, the Communist Party, did. Russia needs truly competitive elections up and down the “power vertical”—from rayon (county) officials to governorships to Duma deputies to senators to the president.

The fourth and final front to retake Russia by the forces of market democracy, such as they are, is at the grassroots level. This is actually the most important and promising challenge. The average Russian citizen’s attitude that the state is his natural enemy is understandable. Laws should be adjusted and formulated to decentralize government power under an ethos that makes clear to government officials that they are empowered only to benefit the people, not to victimize them.

The place to start is with a comprehensive reform of the police, security services, tax authorities, and higher education. The education system needs to be reformed in such a way that students understand the benefits of study, and understand that when they plagiarize and pay bribes to professors they are truly cheating themselves. However, in order for this to happen, a massive legal reform must occur. It is long overdue, and the country is paying an exorbitant price for its tardiness. As Leonid Grigoryev wisely said, corruption is bad, but even worse is citizens’ obedience to bad laws in good faith.[98]

Conclusion

The Russian business environment does not provide conditions and a level playing field for small and medium businesses to develop and operate effectively. The situation in the country has created a maelstrom of vicious cycles, where the people do not trust the government and the government is afraid to make the courts independent, open up the political process, and liberalize the media due to fears of being overthrown by a wave of discontent.

Twenty years after the collapse of Communism, Russia increasingly abuses individuals’ economic and property rights, thereby reducing the attractiveness of the country at home and its global competitiveness abroad. These developments are having dire consequences, including violence, a bloody revolution, and potentially, a civil war, for the country and the citizens, as economic growth slows down and the best and the brightest lose any hope and faith in the future of their country.