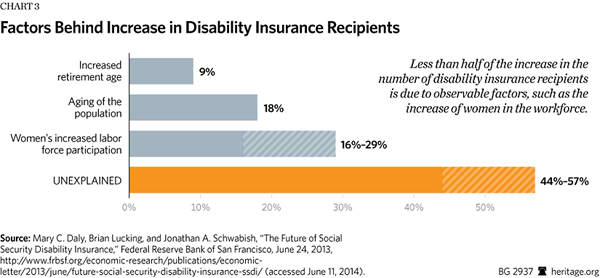

After five consecutive years of deficits, the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) Trust Fund will run dry in just two years.[1] If Congress does not act before 2016, benefits will be cut across the board by almost 20 percent. This would mean a $218 reduction in monthly benefits—from $1,146 to $928—for the average beneficiary,[2] lowering the average benefit below the federal poverty level.[3]

The Disability Insurance (DI) program provides critical income support for workers who become disabled and cannot work to support themselves and their families. However, the DI program has increasingly become an early retirement and long-term unemployment program. Such abuses undermine its integrity and financial stability.

It is essential to preserve the DI program to provide for the millions of truly disabled Americans and their families who rely on it. For individuals who are truly unable to work, a 20 percent cut in benefits would be devastating. Congress should act now to reform the DI program to preserve it for the truly disabled while limiting unnecessary awards and encouraging beneficiaries to return to work.

Rapid Expansion of Disability Insurance

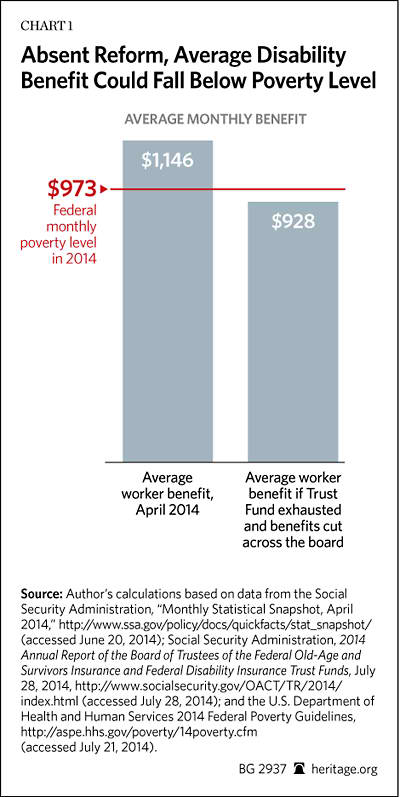

In 1966, 10 years after the DI program began, a little over 1 percent of the population ages 16–64 received DI benefits.[4] Today, that figure has risen to 5 percent of the working-age population. Much of the increase has occurred over the past decade and a half. Since 1991, the recipiency rate has doubled. With increasing numbers of DI recipients come rising costs, roughly doubling real (inflation-adjusted) spending on Disability Insurance since 2000.[5]

This expansion of DI beneficiaries to one in every 20 adults has occurred despite improvements in the health of workers and less physically demanding jobs.[6] If workers are healthier and jobs are less physically demanding, why are more people claiming disability benefits?

Part of the rise in disability benefits can be explained by one-time factors that should run their course and not affect future rolls, but about half the expansion is likely the result of programmatic changes that could cause DI rolls to continue to increase.

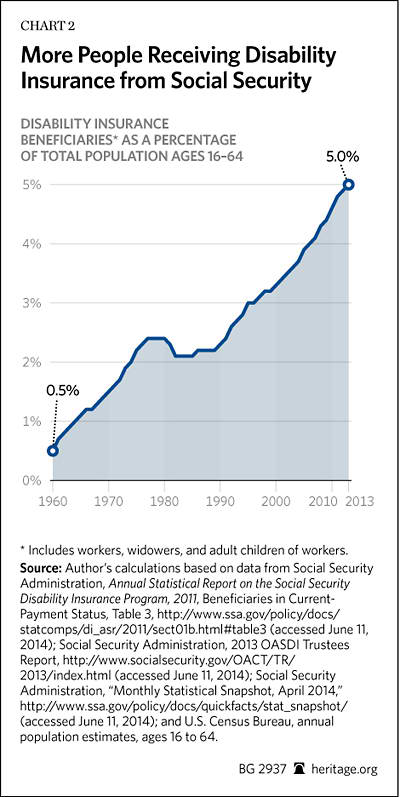

Demographics have contributed to expansion of the DI program. The population of likely disability beneficiaries has expanded both because of the aging baby-boom generation and the increase in Social Security’s normal retirement age. Additionally, higher labor force participation by women has increased the number and percentage of workers eligible to receive DI. A study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta examined the increase in DI beneficiaries since 1980 and concluded that these three factors account for 43 percent to 56 percent of the increase: increased Social Security retirement age (9 percent), aging of the population (18 percent), and increased participation of women in the labor force (29 percent).[7]

The remaining 44 percent to 57 percent of the rise in DI beneficiaries—roughly 3 million beneficiaries—remains unexplained.[8] Among other possible causes, this unexplained increase may stem from broadening of disability definitions and qualifications and an increase in the value of benefits.

Beginning in 1984, Congress expanded disability qualification standards to incorporate not just a specific list of impairments, but also more subjective measures of a person’s ability to work, such as pain and depression. Today, more than half of all disability awards are given to individuals with musculoskeletal disorders or mental impairments.[9]

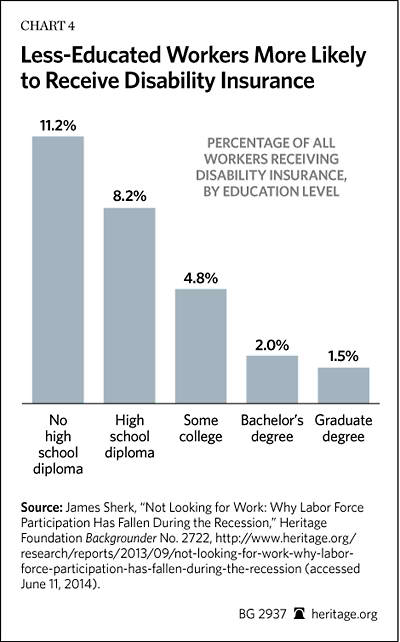

Furthermore, disability benefits have become increasingly valuable to lower-income workers. Although the benefit formula to determine disability benefit levels has not changed, rapid income growth at the top of the income scale has pushed up the index used to calculate DI benefits. From 1979 to 2012, the real average wage that is used to calculate DI benefits increased 22 percent while usual weekly earnings of workers with less than a high school degree fell 28 percent.[10] Consequently, replacement rates (the percent of income replaced by DI benefits) for low-wage workers have risen over time, making DI benefits more attractive to this group.[11] A Heritage Foundation study showed a direct correlation between level of education and DI recipiency: More than 11 percent of all workers with less than a high school degree receive DI benefits, compared with less than 2 percent of workers with a college or graduate degree.[12]

As DI benefits have become more accessible and more valuable, the program has increasingly been used to support early retirement and long-term unemployment.[13] Although the Social Security trustees estimate that the long-run DI recipiency rate will be about equal to its 2013 level, there is reason to believe the DI program will continue to expand, particularly if the economy continues to perform below potential. The Federal Reserve Board projects a higher long-run disability recipiency rate than the Social Security trustees’ estimate, and the Social Security trustees have consistently underestimated future recipiency rates.[14]

Status of the DI Trust Fund

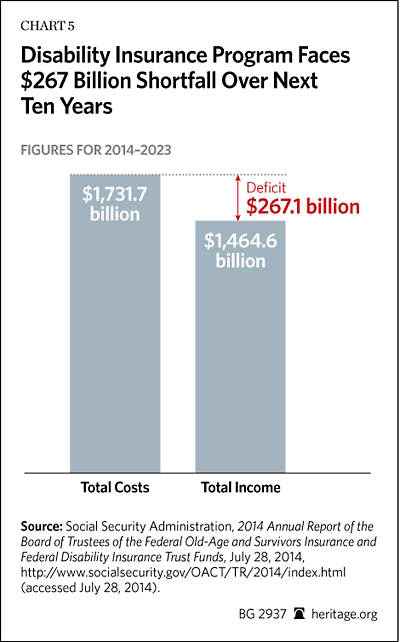

In 2013 the DI program marked its fifth straight year of deficits, with the trust fund declining $32.3 billion (26 percent) from $122.7 billion to $90.4 billion. Each dollar in benefits was met with only 75 cents in payroll tax contributions. According to the Social Security trustees’ intermediate projections, the DI program faces a 10-year projected shortfall of $267 billion.

In actuarial terms, the 2013 deficit amounted to 0.32 percent of taxable payroll. To keep the DI trust fund solvent over the next 75 years, benefits would need to be cut by almost 20 percent immediately or the DI payroll tax would need to increase 17 percent. As discussed below, the program’s history of shortfalls suggests that these estimates may understate the true shortfall.

As the DI program continues to pay benefits in excess of contributions, the DI trust fund is projected to be exhausted at the end of 2016. At that point, incoming contributions will be sufficient to cover about 80 percent of benefit payments. Absent legislation to reform the program or reallocate or borrow resources, benefits will be cut across the board when the trust fund runs dry.

Reallocation or Borrowing Without Reform Would Be a Mistake

In anticipation of the DI trust fund exhaustion, Congress will likely consider reallocating revenues from the Old Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) trust fund to the DI trust fund. Unless accompanied by reform that makes the DI program solvent over the long run, this would be a mistake. A straightforward reallocation would not only prevent necessary reforms, but also shorten Social Security’s solvency and increase near-term deficits because all that is left in the Social Security Trust Fund is IOUs.

In 1994, the DI trust fund faced insolvency, and Congress reallocated a portion of the payroll tax revenues from the Social Security program to the Disability Insurance program. Despite a 50 percent increase in the DI payroll tax rate since 1994, the DI trust fund once again faces imminent insolvency.[15] The DI program needs structural reforms to address rapidly rising rolls, not another reallocation that will allow abuse of the program to continue to grow.

Reallocation sounds like a technical, perhaps inconsequential action, but “raid” would be a more appropriate description. Every dollar of revenue reallocated to the DI trust fund is a dollar of deterioration in the Social Security Trust Fund. As a result, the Social Security Trust Fund would run out of money sooner, and more retirees would be subject to a nearly 25 percent cut in benefits. Absent a reallocation, the trustees project that the Social Security Trust Fund will remain solvent and able to pay full benefits through 2034. Paying for the DI shortfalls would move this date forward one year to 2033.

Since the Social Security Trust Fund exists only on paper as $2.7 trillion in IOUs, a reallocation to the DI trust fund would increase near-term budget deficits on a dollar-for-dollar basis. Every dollar borrowed from the Social Security Trust Fund would first need to be borrowed from the public.

The 2013 DI shortfall was $32.2 billion, and the 2014 shortfall is projected to be $32.3 billion. Based on current projections, a reallocation of DI benefits of the magnitude necessary to prevent benefit cuts would add an average of $27 billion in annual deficits over the next 10 years, or $267 billion in total.

Given the DI program’s substantial and fundamental shortfalls, lending money from the Social Security Trust Fund to the DI program would be reckless without first enacting reforms to increase its solvency. No bank would loan money to a bankrupt company without at least a credible plan to emerge from bankruptcy, and the DI program should be no exception. At a minimum, the DI program must enact reforms to keep it solvent for the foreseeable future before Congress considers reallocating or loaning funds to the program.

Both the OASI and DI programs are structurally insolvent and in need of fundamental reform. The fact that the disability program will become insolvent sooner than Social Security should not mean that Social Security should bail out DI. A race-to-the-bottom approach such as this would encourage moral hazard, prevent or delay necessary reforms, and increase budget deficits.

Disability Costs Magnified by Medicare Costs

After two years on the rolls, disability beneficiaries are eligible to receive Medicare benefits regardless of age.[16] This two-year waiting period can discourage some individuals—primarily those who are more capable of work—from turning to the DI program. However, the Affordable Care Act reduces this deterrent effect by making many recently disabled beneficiaries eligible for health insurance subsidies during the two-year waiting period.

In 1975, DI beneficiaries accounted for about 8 percent of total Medicare recipients.[17] In 2012, DI beneficiaries accounted for 19 percent of Medicare recipients.[18] Providing Medicare benefits for a growing population of disability beneficiaries is extremely costly, adding about $80 billion in general revenue costs.[19]

Disability recipients are unlikely to leave the program. Fewer than 4 percent of beneficiaries leave the rolls for work before retirement.[20] Rising health care costs translate into higher real DI benefits over time. Rising benefit values will encourage more DI applications and will discourage beneficiaries from returning to work. Consequently, total government spending on DI beneficiaries will rise faster than inflation.

Immediate Reform Is Necessary

The DI trust fund is nearly depleted. Millions of disabled Americans rely on the DI program as their sole means of income, yet abuse of the program threatens its ability to provide for the truly disabled. Every dollar of benefits that goes to an able-bodied worker is a dollar that is not available to those who are physically unable to work. Without reform, all beneficiaries could face a nearly 20 percent cut in benefits beginning in 2016. Such cuts would be devastating to those who have no ability to earn income. Reforms to the judicial process and continuing disability reviews, as well as new flexibilities in the initial determination and benefits period could help to preserve the DI program for those who need it most. Congress should act now to reform the DI program and do so without exacerbating Social Security’s shortfalls.

—Rachel Greszler is Senior Policy Analyst in Economics and Entitlements in the Center for Data Analysis, of the Institute for Economic Freedom and Opportunity, at The Heritage Foundation.