About the Author

William T. Wilson, PhD, is a senior research fellow in the Asian Studies Center, of the Kathryn and Shelby Cullom Davis Institute for National Security and Foreign Policy, at The Heritage Foundation.

In the 14 years of the new millennium, Southeast Asia has had some of the fastest growing economies in the world. Indonesia’s economy has been cruising at 6 percent annual growth—but will its lack of infrastructure and its commodity dependence soon reveal some cracks in its economy? The remarkable growth in the Philippines will not last unless domestic investment is elevated. Thailand’s growth has stalled amidst political turmoil, and it is currently in a classic credit bubble. Vietnam still generates impressive growth, but it has a banking problem, high inflation, and ubiquitous corruption.

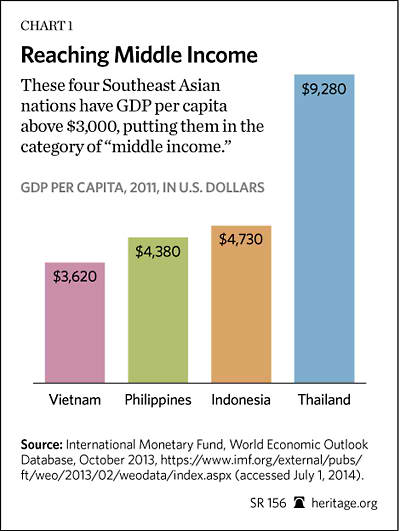

Are these countries entering the classic middle-income trap (MIT)? The MIT is generally defined as the slowdown in growth that occurs once developing countries reach middle-income levels. It is constructive to examine Southeast Asia, as it is the part of the emerging world that has most notably defied MIT tendencies. While only 13 developing countries avoided the middle-income trap since 1960, five of them were in East Asia.[1]

According to the World Bank, there are currently 145 emerging or developing economies in the world. If history holds, relatively few of these economies are destined to become high-income and will become ensnared in the powerful MIT. The World Bank explains that “after exceeding the poverty trap of $1,000 gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, many emerging market countries head rapidly to the middle income ‘take off stage’ of $3,000 per capita GDP, but as they reach the middle-income range, they experience long-term economic stagnation.”[2]

While the causes of the MIT are multifaceted, there does appear to be one consistent cause among many of them. As developing countries hit their early growth spurt and wages rise, manufacturers often find themselves unable to compete in export markets with lower-cost producers elsewhere. Yet, they still find themselves behind the advanced economies in their ability to produce higher-value products. The biggest challenge, then, is moving from resource-driven growth that depends on cheap labor and capital to growth based on high productivity.

Recent history is littered with examples of seemingly extraordinary rates of economic growth that were not what they seemed. During the first two decades after World War II, for example, it was a widely held belief that the Soviet Union was outpacing the United States in economic growth. Some economists at the time had even come to admire the Communist model of central planning. Unfortunately for the Soviets, the relatively rapid growth in output could be fully explained by the rapid growth in their factor inputs: a rapid expansion in their labor force, significant increases in educational levels, and above all, massive investments in physical capital.

Economic growth that is based exclusively on factor accumulations, rather than on growth in output per unit of input or productivity, is inevitably subject to diminishing returns. It was simply not possible for the Soviet economy to sustain the high rates of growth in labor force participation, education levels, and its physical capital stock that had prevailed in the early postwar years. The result was a slowdown in productivity growth.[3] Without the sustenance of productivity growth, Soviet economic growth eventually faltered.

Productivity growth is the most important gauge of an economy’s long-run health. Nothing is more critical in determining living standards over the long run than improvements in the efficiency with which an economy combines its inputs of capital and labor. Most economists focus on labor productivity, which is an incomplete gauge of efficiency because firms can boost output per man-hour by investing more and equipping workers with better machinery. A better gauge of an economy’s use of resources is “total factor productivity” (TFP), which assesses the efficiency with which both capital and labor are used. Once a nation’s labor force stops growing and an increasing capital stock causes the return on new investment to decline, TFP becomes the main source of economic growth.

The illusion of sustainable growth was not only limited to the command economies. The unusually rapid and protracted growth in the then newly industrialized economies (NIEs) of East Asia (Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan) from the 1960s until the 1980s led to the widespread belief that productivity growth in these economies, especially in their manufacturing sectors, had been extraordinarily high. But seminal research[4] showed that the NIEs’ economic growth was mainly due to factor accumulation and the sectoral reallocation of resources.

All four economies had experienced sizable increases in their labor force participation, leading to natural increases in output per capita, or average living standards. In particular, however, they had been rapidly accumulating capital, leading to more capital per worker, and in turn, higher labor productivity. Unlike the command economies of the Communist era, however, factor accumulation in the four NIEs contributed substantially to growth because these economies on the whole allowed the increasing amounts of labor and capital to move from the less productive sectors to the more productive ones. It is this factor accumulation, combined with eventual gains in productivity, which allowed them to escape the MIT.

Japan’s dismal rate of economic growth over the past two decades is largely the result of lackluster productivity increases. (According to the Conference Board, TFP growth averaged only 0.5 percent between 2000 and 2013.[5]) As its post–World War II rate of factor accumulation began slowing down, particularly capital accumulation, so did its overall rate of growth.

Part of the jump in America’s labor productivity during the “new economy” era of the late 1990s reflected a sharp rise in domestic investment as a share of GDP (that is, capital accumulation). As this investment share returned to historically normal levels last decade, so did U.S. real GDP growth.

This Special Report explores the root causes of the MIT and offers policy recommendations on how developing countries can avoid it. The MIT issue is most critical today because there are now 55 developing countries in the upper-middle-income range with combined populations of over two billion.[6] This Special Report focuses on four nations in Southeast Asia—Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam—because these have been some of the fastest growing since the turn of the millennium, and at least for now, appear resistant to the MIT.[7]

The Determinants of Middle-Income Traps

Protracted economic slowdowns that pull emerging economies into the MIT can be generated by a host of factors. This Special Report examines a broad range of factors that have been consistently shown to impact TFP and, consequently, economic growth. In a similar methodology used by Shekhar Aiyar and his colleagues,[8] 13 explanatory variables are grouped into six categories: (1) macroeconomic fundamentals, (2) demographics, (3) institutions, (4) trade structure, (5) infrastructure, and (6) wars and civil conflicts.

Macroeconomic Fundamentals. This section examines credit growth, government size, and investment freedom. While slower growth is hardly prima facie evidence of an MIT (it could simply be a cyclical downturn), real GDP seems a logical place to check first. Charts 2, 3, 4, and 5 show three-year moving averages of annual real GDP growth. The smoothing of the data takes out some of the underlying economic turbulence from the crisis and post-crisis period to better ascertain a trend.

- Indonesia’s economy has remained robust and resilient, setting an impressive pace of approximately 6 percent during the past five years and also growing at a 6 percent pace during the 2008–2009 crisis.

- Since 2000, the Philippines has experienced a clear acceleration in growth, averaging almost 6 percent growth over the past three years.

- Since the middle of the past decade, Thailand has witnessed a marked deceleration in growth. After growing at 5 to 6 percent during much of the past decade, it has dropped to a three-year moving average of approximately 3 percent.

- Vietnam has had remarkable growth over the past two decades, although it has leveled off closer to the 5 percent range in recent years.

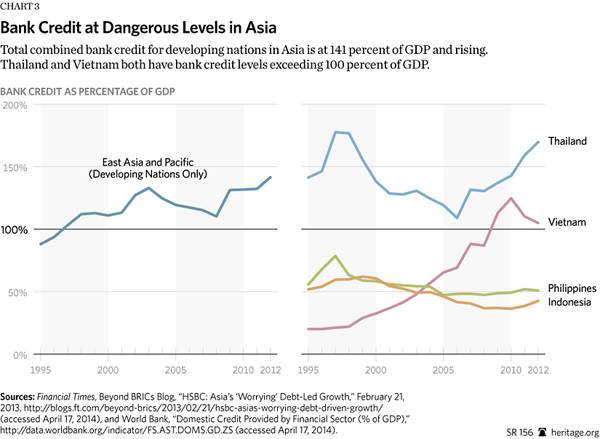

1. Credit Growth. It is well known that loose credit has played a big role in driving Chinese growth in recent years, but the rest of Asia could also have a debt problem, says Frederic Neumann of HSBC.[9]

Bank credit as a share of GDP in Asia (excluding Japan) is now running at much higher levels than during the 1997–1998 Asian financial crisis. Since then, this ratio has risen from 110 percent to over 140 percent—a steep rise that has seemed to go unnoticed. Some believe that a major crisis in Asia is avoidable today given that much of this debt is now denominated in local currencies and that exchange rates are generally flexible, unlike the situation during the 1997–1998 crisis. Nevertheless, given their heavy debt levels, many nations in Asia will be vulnerable should there be a sharp rise in global interest rates.

A major reason why Asia managed to rebound quickly from the 2008 crisis and maintain strong growth afterwards can be explained by the precipitous rise in leverage that helped offset recessionary conditions in the West. In fact, according to Neumann of HSBC, there are mounting signs of a rising credit intensity of GDP growth in Asia: While lending growth slowed in many Asian markets over the past year, it slowed by less than GDP growth slowed (especially when factoring in soaring bond issuance). In short, more and more debt is needed to generate one percentage point of GDP growth.[10] If the most recent financial crisis has demonstrated anything, it is the difficulty of resuscitating economic growth after a debt binge.

Aggregate figures can hide important country-by-country differences. At a steady 40 to 50 percent of GDP, both Indonesia and the Philippines seemed to have managed their growth in domestic credit over this most recent cycle relatively well. Vietnam and Thailand, however, are different stories. While Vietnam’s domestic banking credit share of GDP has finally leveled off in recent years, the banking system is riddled with bad loans and most certainly will require a large-scale bailout, which could negatively impact the economy for years to come. Thailand is in an even worse situation, in which rapid domestic credit growth since the middle of the past decade has fueled consumer debt and spending.

Could the rising credit intensity of Asian economic growth be a normal sign, a byproduct of the region reaching greater economic maturity? Not necessarily, according to Neumann. In order for Southeast Asia to continue growing at healthy rates, it needs continuous improvements in productivity, which is less likely to happen if investment efficiency declines in the flood of easy credit.

Moreover, because global interest rates remain low, the leverage is continuing to increase. And with the Bank of Japan joining the Western central banks in aggressive quantitative easing, this trend toward greater leverage in the region is likely to continue.

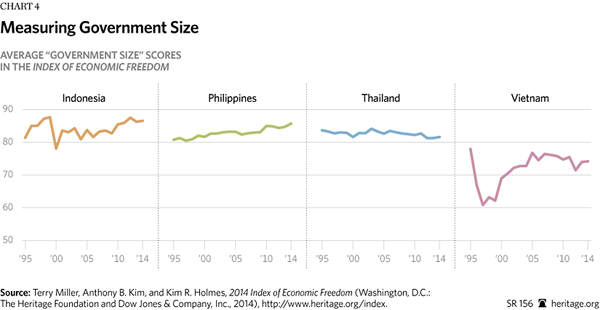

2. Government Size. Growth of government is often a sign that a growth slowdown is only a question of time, particularly if the growth in spending is viewed as permanent. The Heritage Foundation employs the “Fiscal Freedom” and “Government Spending” categories in the Index of Economic Freedom[11] to measure government size. Fiscal freedom captures the burden of taxes by measuring the overall tax burden from all forms of taxation as a percentage of total GDP. Government spending must eventually be financed by higher taxation (including the inflation tax), which leaves fewer resources for the private sector.

- Both Indonesia and the Philippines have made reasonable improvements in limiting government size in recent years.

- Indonesia’s public debt is only 24 percent of GDP. In the Philippines, public debt is approximately 50 percent of GDP.

- Thailand’s public finances are relatively respectable; public debt is 45 percent of GDP. (It was 24 percent of GDP in 2008.)

- Vietnam has not improved its relative standing since 2005, and its public debt is above 50 percent of GDP. Public expenditures are a sizable 31 percent of GDP.

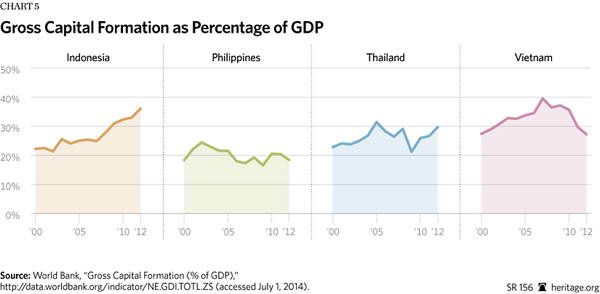

3. Domestic Investment. Investment provides a stimulus to economic development, and the rate of investment reflects the infusion of requisite capital to support the development process. High rates of domestic investment are necessary conditions for middle-income countries to maintain elevated growth levels. A rate of 30 percent of GDP is not uncommon among healthy developing economies.[12]

Indonesia comes out on top in this category, with gross investment’s share of the economy exceeding 30 percent for four consecutive years. If this high rate of investment were combined with falling GDP growth rates, it would be a concern because it might imply declining returns on capital (but GDP growth rates have accelerated, not slowed down). There is, however, one possible caveat: Indonesia runs a relatively large current account deficit because domestic spending exceeds domestic savings. As witnessed during the 1997–1998 emerging-market crisis, a flight of foreign capital easily could destabilize the economy.

The Philippines’ rate of domestic investment runs a full 10 percent of GDP below that of Indonesia and has been generally flat since 2000. With a per capita GDP of only $4,700, this should be some cause for concern. The Philippines’ marginal product of labor would receive a considerable boost if capital formation was much stronger.

Vietnam’s domestic investment has been strong for some time although it has significantly leveled off in recent years. In the 2014 Index of Economic Freedom, Vietnam is ranked as one of the lowest in investment freedom throughout the world.[13]

Thailand, Southeast Asia’s traditional manufacturing hub, has witnessed strong investment trends in recent years. However, as reported in the Financial Times, “more than $15 billion of planned foreign and domestic investment in Thailand is on hold because of political turmoil…. [T]he backlog highlights the economic damage Thailand is suffering from the ongoing crisis that is paralyzing government and playing out as foreign investors from Japan and elsewhere outsource production to cheaper neighboring states.”[14] Continued political turmoil in Thailand is destined to dramatically slow domestic investment (particularly foreign direct investment) and tourism.

Demographics

With the right set of economic policies, a favorable demographic profile can be a boon to a nation’s rate of growth. This section examines the dependence ratio, urbanization, and the female labor participation rate.

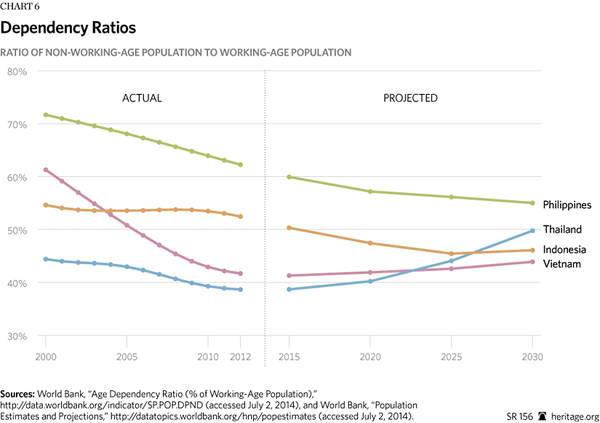

4. The Dependence Ratio. Recently, most economists have come to the view that the changing age structure of the population, rather than population growth itself, can significantly alter economic development. The source of population growth and its timing are the critical factors.

Unlike working-age individuals, the young and old tend to consume more output than they generate. As a consequence, the value of output per capita tends to be boosted when the population of working-age individuals is relatively large, and tends to be depressed when a relatively large part of the population consists of young and elderly dependents.

Developing countries that are entering their demographic transition have a unique chance to convert their population dividend into higher growth from this “demographic dividend.” Unfortunately, this demographic shift creates only one window of opportunity. Low fertility rates eventually lead to a rising proportion of older people, raising the dependence ratio as the working population goes from caring for children to caring for parents and grandparents. If a country acts wisely before and during this transition, a special window opens up for faster economic growth and human development.

The 20th century has provided numerous examples of how demographic transitions can give developing countries an opportunity to accelerate development. Japan’s economic miracle in the early postwar period was highly correlated with the shrinkage in its dependence ratio. The same is true of the remarkable economic ascendancy of the four tiger nations (South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and Hong Kong). In 1950, women of the tiger nations had an average of six children; today, they have fewer than two. As a result, between 1965 and 1990, the working-age population increased four times faster than the number of young and elderly dependents.[15]

Conversely, when this window closes, holding everything else equal, a natural economic slowdown is likely as the elderly place an increasing economic burden on the working-age population. For example, China’s recent economic slowdown (from 10 percent to 7.5 percent) has partially been attributed to the fact that the working-age population peaked in 2011 and is now declining.

Since 2000, Vietnam has experienced by far the largest demographic dividend, with its dependency ratio falling an enormous 20 percentage points (from 61 percent to 41 percent). This gave Vietnam a one-time enormous potential lift in growth. The Philippines also witnessed a sharp drop of 9.4 percent points.

Indonesia and Thailand experienced more modest drops in their dependence ratios, with declines of 2.2 percent and 5.7 percent, respectively. Currently, at 39 percent, Thailand has the most favorable demographic ratio, while the Philippines has the worst, at 62 percent.

More important, how will these dependence ratios change over the next 15 years (2015–2030)? Thailand has clearly exhausted its demographic dividend, and with the working-age population currently growing 0.4 percent per year, Thailand’s dependence ratio is expected to rise approximately 11 percent. What the demographic dividend gave, it now takes away.

Vietnam has also experienced a sharp drop in the growth rate of its working-age population (from 2.9 percent to 1.3 percent from 2000 to 2012), but its dependency ratio is expected to drop by only 2 percent by 2030.

Both Indonesia and the Philippines fare better, with their dependence ratios continuing to decline modestly in the coming years. At 2.2 percent, the Philippines currently has the fastest growth of the four countries in working-age population.

5. Urbanization. In the earlier stages, a good share of economic growth for many developing economies emanates from the TFP gains derived from urbanization. As labor switches from low-productivity sectors (such as agriculture) to higher-productivity sectors (such as manufacturing and modern services), the TFP can provide a boost in per capita income. This “sectoral” shift in labor is one reason why developing economies can grow much faster than their developed counterparts. According to the World Bank, a portion of China’s rapid TFP growth over the past two decades has been the result of very rapid urbanization, which has now surpassed 50 percent.[16]

At some point, however, this process naturally begins to slow down as the country becomes increasingly urbanized. Much work in the past suggests that many growth slowdowns are declines in TFP brought on by diminishing returns to urbanization.[17]

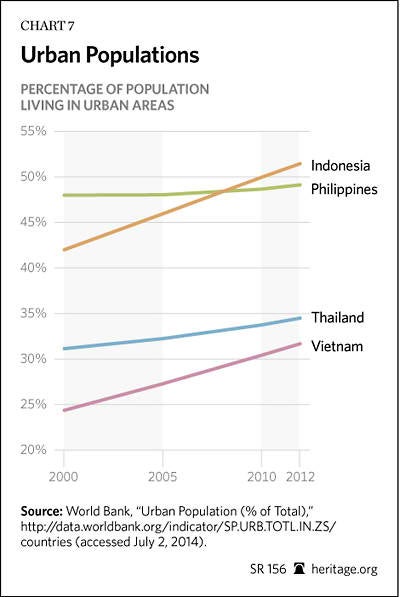

- Since 2000, Indonesia and Vietnam have achieved the largest gains in urbanization (9.4 percent and 7.3 percent, respectively).

- Indonesia and the Philippines are already 50 percent urban.

- Only one-third of the population in Thailand and Vietnam is urban, meaning that the TFP could significantly increase growth in the coming decades if both countries continue to urbanize.

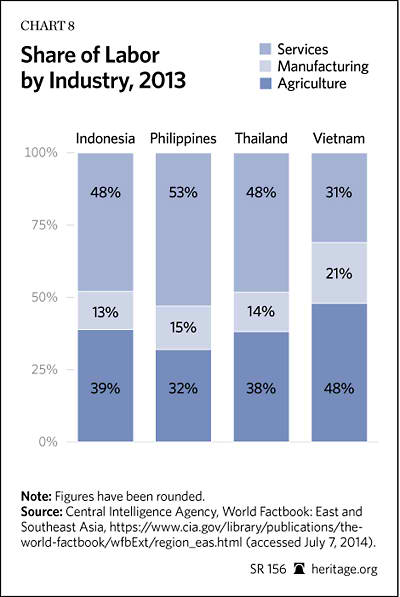

A more precise way of looking at the potential sectoral shift is to compare the employment distribution by sector. These four Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries still have considerable employment in agriculture. In fact, in Thailand and Vietnam, agriculture is the largest employer.

6. Female Participation Rate. The female work participation rate in some Asian countries is low by global standards, and higher female participation is a key to offsetting Asia’s declining demographics.

- The female work participation rate is only 50 percent in Indonesia and the Philippines (the average for developing Asia is 63 percent). These participation rates should gradually rise, providing faster growth in the workforce.

- Thailand’s female work participation rate is almost two-thirds, while Vietnam’s is over 70 percent, leaving much less room to raise participation rates.

Institutions

Many economists studying economic development have come to the conclusion that institutions—which shape the incentives of a society—are a fundamental determinant of economic performance and long-run economic growth.[18] It is only natural that middle-income countries encounter barriers to growth as factor accumulation eventually slows down and the economy experiences diminishing returns. To break through this barrier and avoid the MIT, developing countries will have to improve their institutions. Good institutions provide the incentives for hard work, the acquisition of human capital, and in turn, better technology and innovation.

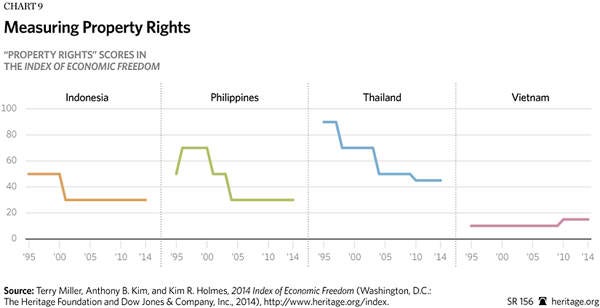

7. Property Rights. The institutional environment is determined by the legal and administration framework within which individuals, firms, and governments interact to generate wealth. Property rights provide an assessment of the ability of individuals to accumulate private property, secured by clear laws that are fully enforced by the state.

During the late 1990s, Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines all had property rights ratings at or above the world average (approximately 50 of a possible 100). Contrary to conventional wisdom, however, the late 1990s (after the Asian financial crisis) were not a stellar time for improvement in these countries’ institutions, and property rights ratings declined or did not improve. According to the 2014 Index of Economic Freedom:

- While property rights are generally respected in Indonesia, their enforcement is inefficient and uneven. Corruption remains endemic.

- In the Philippines, corruption and cronyism are widespread in business and government. Delays and uncertainty negatively affect property rights.

- Thailand has an independent judiciary that is generally effective in enforcing property and contractual rights but remains vulnerable to political interference.

- Vietnam has serious institutional problems that will eventually hamper growth. The judiciary is subservient to the ruling Communist Party, which controls courts at all levels. Private property rights are not strongly respected.

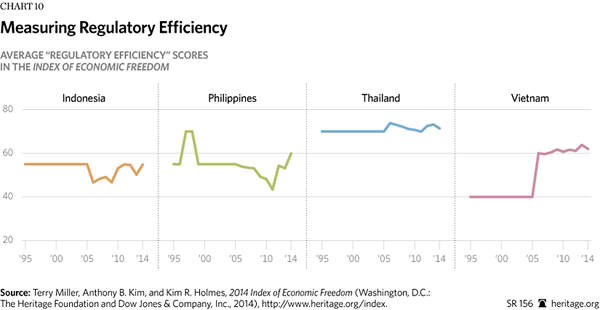

8. Regulation. The proxy for regulation is The Heritage Foundation’s “Business Freedom” category in the Index of Economic Freedom. Business freedom is an individual’s right to establish and run an enterprise without undue interference from the state. Burdensome and redundant regulations are the most common barriers to the free conduct of entrepreneurial activity.

- Ranking below the global average of 64, Indonesia’s overall regulatory efficiency is weak. Launching a business takes longer than a month and the regulations concerning the creation and termination of employment relationships are relatively costly.

- The Philippines has cut the time needed to deal with licensing requirements, but the government subsidizes state-owned and state-controlled corporations in the power, food, health care, and agricultural industries.

- Business freedom has been relatively high and stable in Thailand. No minimum capital is required to start a business, but state-owned enterprises (SOEs) account for more than 40 percent of GDP.

- In Vietnam, launching a business takes 10 procedures on average, and no minimum capital is required. The government influences prices through SOEs and controls bank interest rates.

Trade Structure

9. Commodity Intensity and the Resource Curse. Between early 2003 and mid-2008, oil prices climbed by 330 percent in dollar terms, with metals and minerals making similar advances. The real price of agricultural products was broadly stable, especially in the developing countries early on, but then rose sharply from 2006 to 2008 (during which time global food prices doubled).

While commodity booms are often accompanied by a temporary lift in economic growth for commodity exporters, economic dependence on commodities has generally been associated with slow growth and economic development over the longer term. This so-called resource curse, which has been thoroughly explored by the academic literature,[19] is thought to work through a number of important channels. One is a tendency for the commodity boom-bust cycle to accentuate both changes in government spending and economic cycles, which can discourage long-run economic development.

Another is a tendency for exchange-rate appreciations associated with commodity booms (the so-called Dutch disease) to weaken the competitiveness of the non-commodity sectors of the economy.

Lastly, but perhaps most important, is a tendency for countries that enjoy high commodity revenues to waste their windfalls and not invest them in wealth-generating investments or activities. Commodity endowments are well known to lead to rent-seeking behavior and corruption. There is a very high correlation between resource dependence and corruption.

The resource curse is not a significant issue for Southeast Asia and the Pacific region. Rapid industrialization had made the region the least dependent on commodity exports of any major emerging-market region (representing just 20 percent of merchandise exports, down from almost 60 percent as recently as 1985).

As one of the world’s largest suppliers of minerals and agricultural products, Indonesia is an Asian exception. Commodities are 55 percent of total exports, and 13 percent of GDP. Declining commodity prices over the past two years have led to deterioration in Indonesia’s current account, which helped lead to a significant exit from Indonesian assets.

On the plus side, lower commodity prices should increase the relative profitability of manufacturing and help Indonesia develop its industrial base.[20]

Infrastructure

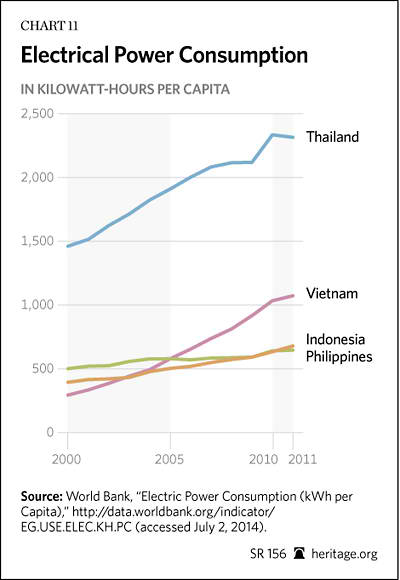

10. Power Consumption. Any developing country looking to build a manufacturing base or increase its rate of urbanization should have an electricity grid to match its current needs or ambitions.

- According to the World Bank’s 2014 Ease of Doing Business, Indonesia continues to be straightjacketed by electrical power infrastructure problems, while the Philippines is just as bad, with per capita electricity consumption barely growing over the past decade.

- Thailand’s large manufacturing sector consumes much electricity, while Vietnam’s per capita consumption has risen surprisingly almost fourfold over the past decade.

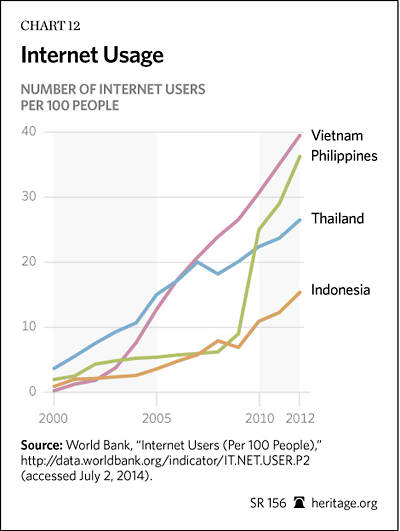

11. The Internet. The Internet has revolutionized communication, making obtaining information easy, quick, and cheap. Rising Internet penetration rates would seem a necessary condition in avoiding the MIT. According to the International Telecommunications Union, high-income countries had an Internet penetration of 76 percent in 2012.[21]

- In early 2000, Vietnam had almost no Internet users; by 2012, four in 10 Vietnamese were online.

- The Philippines witnessed an explosion in Internet usage that began five years ago and has now surpassed the emerging-market average of 18 percent.

- Like the rest of its infrastructure, Indonesia has poor Internet penetration (15 per 100).

- For a country with a relatively high per capita income and decent physical infrastructure, Thailand has poor Internet penetration.

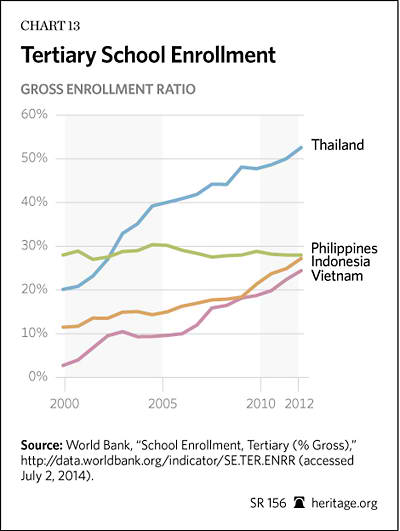

12. Education. A rapid expansion of the secondary school system may not be enough to allow a developing country to escape the MIT. Increasing the share of the population with a tertiary education may be necessary.[22] This necessity is consistent with the importance of moving up the technology ladder. Slowdowns are less likely in countries where high-tech products account for a large share of exports. Broad-based growth in tertiary education was precisely how the Republic of Korea achieved its successful transition from middle-income to high-income status.

- Vietnam and Indonesia have made moderate progress since 2000, but should probably focus on increasing the adult share of secondary education over the next decade.

- The Philippines’ tertiary education has flat-lined over the past 15 years, foreboding an economy that is destined to copy and “service the world” for some time to come.

- If they are able to regain political stability in the coming years, Thailand’s manufacturers, such as the auto-parts makers, might be able to innovate and create new and better products in the coming years.

13. War and Civil Strife. After socialism, nothing has negatively impacted productivity and growth more than war and civil strife throughout the emerging world. When normally productive inputs (people and capital) are distracted from normally productive activities, economic growth is a big casualty.

Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines have been largely devoid of any significant civil discord in recent years. Thailand is an entirely different story. In the past, Thailand’s economy has always tended to bounce back vigorously from military coups and civil strife. This time could be different.[23]

To outside observers, it appears that the Thais’ faith in their national institutions is crumbling. The government that the army installed after the 2006 coup mismanaged the economy. The courts have dissolved several of former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra’s proxy governments. In short, Thais are left with no one to trust.

The economy is quickly deteriorating and the economic slowdown has been broad-based. Hotel and flight bookings to Bangkok have plummeted as the weeks of turmoil have stretched into months. More than $15 billion in foreign investment is on hold. The longer the infrastructure projects and measures to improve productivity among Thailand’s rapidly aging population are held up, the more Thailand risks losing out to some of its regional neighbors. Moreover, consumer spending this time would be unlikely to rebound rapidly because of the household debt. As if things were not bad enough, the May 2014 military coup could lead to economic sanctions against Thailand.

Mother’s Milk: Total Factor Productivity[24]

As discussed, total factor productivity ultimately determines a country’s living standard over the long run. All middle-income nations at some point reach diminishing returns from their labor and capital inputs. Increasing the efficiency of these inputs at this stage then becomes critical.

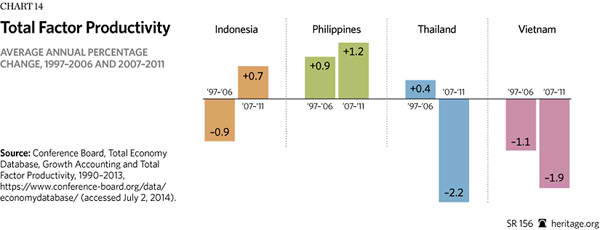

Chart 14 shows how the four ASEAN nations fared over two different periods.

The first period coincides with the Southeast Asian financial crisis, and TFP growth rates plummeted more or less across the board in 1998. (Indonesia’s fell 18 percent that year.) TFP does not necessarily have to fall during economic slowdowns, but the crisis had become destructive to the financial system over this period.

The 2007–2011 period is more suitable to focus on for two reasons. First, Southeast Asia emerged from the 2008 global crisis relatively unscathed, and second, it provides a picture of conditions under the current business cycle.

Three factors are immediately apparent: (1) TFP growth is anemic, considering that these nations are in their “catch-up” phase with a per capita GDP of $3,000 to $12,000. Labor and capital accumulations remain the primary economic engines, and TFP has not recently been a major contributor to GDP growth. (2) Both Thailand and Vietnam had declining TFP rates in recent years, implying declining efficiency of inputs. (3) While Indonesia and the Philippines have positive rates, they are low compared to other fast-growing emerging economies. India and China, for example, have maintained TFP rates in excess of 3 percent for over a decade.

Middle-Income-Trap Statuses

Thailand: Already Trapped. At the time of publication, the political turmoil in Thailand shows no sign of subsiding, and it has already heavily impacted foreign direct investment and economic growth.

Data on Thailand’s TFP growth are not available for the past two years but it might very well have been negative given the political disruptions and slowing growth. Thailand is now entering its “dividend deficit” as the fertility rate has fallen to an average of 1.6 children per woman—from seven in the 1970s. Much of the textile industry has migrated to countries with lower wages, such as the Philippines.

Much of Thailand’s growth over the past decade was the result of a credit bubble. Thailand’s consumers are paying the price, with household debt at the end of 2013 hitting a record at 82.3 percent of GDP, compared with 77.3 percent a year earlier, and 45 percent a decade ago.[25] An inevitable period of deleveraging will be protracted and painful.

On the bright side, Thailand is an exporter of high-tech products such as integrated circuits and cars. A large share of its workforce remains employed in agriculture, meaning that it can still reap a sectoral TFP gain. If it is able to finally resolve its political divide (unlikely anytime soon), it could continue climbing the technological ladder, resuscitating the economy.

Vietnam: An MIT Candidate. Like Thailand’s, Vietnam’s growth was elevated by a credit bubble. It is likely that much of the banking system will need to be bailed out by the state. Vietnamese authorities have made only slow progress in reforming the state’s involvement in the economy. Like China, it has many SOEs. Its initial public offerings of some SOEs in the first quarter of 2014 went poorly, attracting little attention from foreign investors. Its enormous demographic dividend over the past decade, which helped elevate labor force participation and economic growth, is quickly dissipating; corruption is stifling; and it has high structural inflation. Vietnam will have to attract much more direct investment, while improving its transparency.

On the plus side, it is urbanizing fast and building its secondary education infrastructure. It is also a large exporter.

The Philippines: Shaky But Improving. Over the past few years, the Philippines has become one of the world’s fastest growing economies. It seems to be moving in the opposite direction of an MIT. The government has recently made significant efforts to combat corruption, and the level of corporate transparency has improved. While agriculture is still a significant sector, the electronics, apparel, and shipbuilding sectors are growing rapidly. Domestic investment’s share of the economy needs to be elevated in the coming years.

Indonesia: Reasonably Solid. Indonesia’s increasingly modern and diversified economy sailed through the recent economic crisis. It looked solid on most fundamentals, particularly on credit growth and foreign direct investment. The country must, however, improve its overall infrastructure (both physical and cyber) and continue to diversify its economy.

Conclusion

The middle-income trap has become the scourge of the developing world. Thailand, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Indonesia would be wise to take their cues from the success of the Asian economies that were able to transition from middle-income status to high-income status based on their ability to increase productivity by allowing, to the greatest extent possible, the market to allocate assets. The successful countries also pushed their technological boundaries and moved from imitating and importing foreign technologies to innovating technologies of their own.

Strong protection of intellectual property rights was a major factor in elevating TFP in the successful East Asian economies of South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore. According to the World Bank’s Doing Business database, intellectual property rights in these economies rival those in place in Japan, the U.S., and other high-income countries.[26]

Thailand, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Indonesia are currently suffering from low TFP growth, and Thailand and Vietnam are likely in credit bubbles. As former chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers Herb Stein put it in his “Stein’s law”: “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.” All four countries should focus on improving their fundamentals, such as protecting property rights and limiting the size and scope of government. There are other measures that could be used to combat the MIT, such as reforming labor markets to ensure that rigidities do not prevent the efficient firing and hiring of employees.

Avoiding inflation is obviously a necessity. A long period of solid economic growth can be wiped out by one bad bout of inflation. Central Bank independence is critical.

As economist Chris Hartwell points out, openness to trade is crucial to escaping the MIT. In fact, openness to trade only grows more important as diminishing returns to technology set in, because “trade restrictions shrink the market for producers in a particular country in the domestic market; restrictions often bring a whole host of other distortions with them (including the creation of trade-licensing bureaucracies); a country that closes itself off to trade often pursues other growth-dampening policies as well.”[27] Passage of a truly liberalizing Trans-Pacific Partnership would increase trade and investment throughout Asia.

At one time, developing economies looked to the United States and other OECD nations as economic models to emulate. Now, with their reckless fiscal policies, heightened business regulation, and “too-big-to-fail policies” that punish the good and reward the bad at taxpayer expense, emulating the rich club is not such a good idea.

Bottom line: The middle-income trap is avoidable if caught early; it can be escaped with the proper policies.