About the Authors

James M. Roberts is Research Fellow for Economic Freedom and Growth in the Center for International Trade and Economics (CITE ) at The Heritage Foundation.

Ariel Cohen, PhD , is Senior Research Fellow for Russian and Eurasian Studies and International Energy Policy in the Douglas and Sarah Allison Center for Foreign Policy Studies at The Heritage Foundation.

Heritage interns Anton Altman and Kyle Niewoehner made valuable contributions to this paper.

Abstract: Central Asia, especially Kazakhstan—rich in oil and gas, and the world’s largest landlocked country—is the focus of many Fortune 500 companies seeking new business development and market penetration in emerging economies. In the 2012 edition of the Index of Economic Freedom, Kazakhstan’s economy ranks as the 65th-freest in the world. Kazakhstan ranks higher than all other Central Asian countries, and its overall score is higher than the world average in general, and Russia in particular (place 144). There remains much room for improvement—which Kazakhstan can achieve if it pursues additional market-oriented reforms, the rule of law, government transparency, tougher anti-corruption laws, and counterterrorism measures.

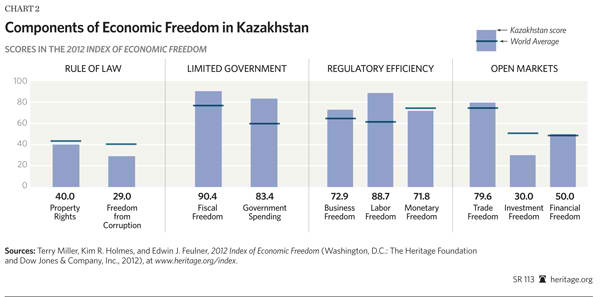

Oil- and gas-rich Kazakhstan, the world’s largest landlocked country, and the four other former Soviet republics in Central Asia—Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan—are the focus of many Fortune 500 companies seeking new business development and market penetration in emerging economies worldwide and those of Eurasia in particular. In the 2012 edition of the Index of Economic Freedom (published by The Heritage Foundation and The Wall Street Journal),[1] Kazakhstan’s score is 63.6 out of 100, making its economy the 65th-freest in the world. In the Asia-Pacific region, Kazakhstan ranks 11th out of 41 countries (higher than all other Central Asian countries). Its overall score is higher than the world average of 59.5 (although its scores were lower than average on Freedom from Corruption and Investment Freedom). However, Kazakhstan has made much progress in its economic development, and can significantly improve its Index standing in the future if it pursues additional market-oriented reforms, including the rule of law.

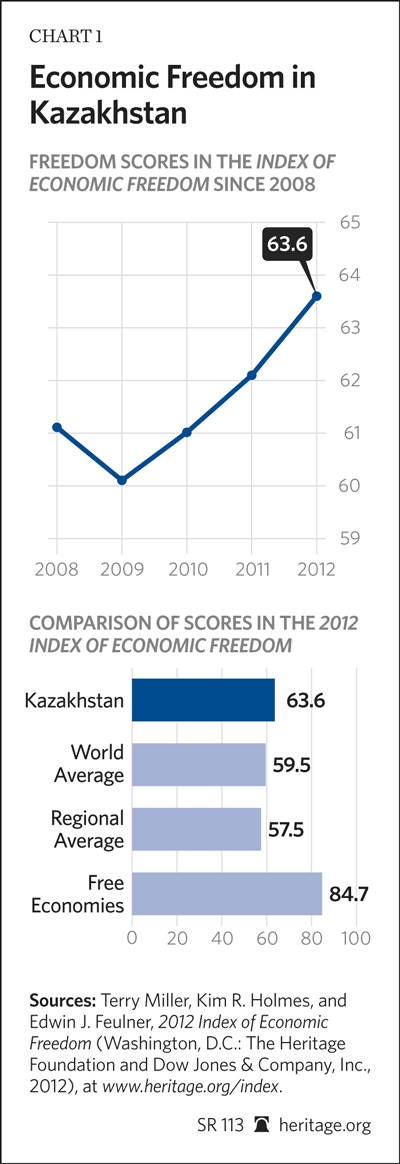

Kazakhstan scores better on Trade Freedom, Business Freedom, and Financial Freedom than its former Soviet peers. The country continues its integration into global commerce and has registered significant increases in private investment from Western companies. There remain, however, some serious obstacles to economic freedom. Kazakhstan continues to suffer from extensive problems with law enforcement and rule of law. These problems were evident most recently last December, when police fired on protesting laid-off oil workers in the city of Zhanaozen, killing at least 16 of them.

Although the government has tried to make economic diversification a priority, that effort has generally been at odds with the reality of a gradually increasing role of the state and oligarchic groups. Kazakhstan and its neighbors still lack full regulatory transparency, efficient judicial institutions, and flexibility of labor laws. Corruption, non-transparent regulations, inefficient dispute-resolution mechanisms, rigid labor laws, high crime rates, and foreign exchange controls are all obstacles to corporate investment.

Nevertheless, as The Economist reports, the “political grip of the authoritarian president, Nursultan Nazarbayev, will be underpinned by relatively strong economic growth and the weakness of the opposition.”[2]

Kazakhstan’s government emphasizes regional economic integration. In 2010, Kazakhstan (and Belarus) joined the Moscow-led Customs Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia, and in November 2011 it joined the Eurasian Union (EuU). These moves complicate Kazakhstan’s future economic freedom trade score, as well as its pending application to join the World Trade Organization (WTO). Although there are short-term gains from the reversion to an inward-looking Eurasian economic sphere represented by the EuU, the experience of the former Warsaw Pact countries that are now EU members strongly suggests that remaining more open to global trade has greater long-term benefits.

Business elites and government officials in Kazakhstan and throughout the region can attract additional foreign direct investment (FDI) if they take concrete steps to improve their scores on other key Index criteria, such as improving and upgrading the legal foundations of the Kazakh market economy, strengthening the court system and professionalism of judges and legal counsels, increasing efforts by the government to fight corruption and changing the local culture that tolerates it, and improving regulatory efficiency. They should buttress structural reforms, rein in government spending, spin off failing state assets, and reduce regulatory burdens (especially regarding the process of attracting venture capital for business start-ups).

Kazakhstan’s Economic Strengths and Weaknesses

Kazakhstan has steadily improved its Index of Economic Freedom score each year since 2009 due mostly to ongoing policy reforms that have enhanced regulatory efficiency. Kazakhstan was among the top 20 countries in the world whose Index scores had improved from 2011 to 2012.

Through these reforms and integration into the global economy, Kazakhstan has racked up solid macroeconomic indicators and impressive economic growth in the past decade that surpasses all other Eurasian states, including Russia. As the Central Intelligence Agency World Factbook notes, Kazakhstan

possesses enormous fossil fuel reserves and plentiful supplies of other minerals and metals, such as uranium, copper, and zinc. It also has a large agricultural sector featuring livestock and grain. In 2002 Kazakhstan became the first country in the former Soviet Union to receive an investment-grade credit rating, and from 2000 through 2007, Kazakhstan’s economy grew more than 9 percent per year. Extractive industries, particularly hydrocarbons and mining, have been the engines of this growth.[3]

Nevertheless—and aware that “Dutch disease”[4] has resulted from too much dependence on exports of oil and other extracted minerals—the government has undertaken an “ambitious diversification program, aimed at developing targeted [non-oil] sectors like transport, pharmaceuticals, telecommunications, petrochemicals and food processing.”[5]

Further analysis of Kazakhstan’s Index performance in the four major areas measured (Rule of Law, Limited Government, Regulatory Efficiency, and Open Markets) in the following paragraphs reveals the country’s strengths and weaknesses in greater detail.

Rule of Law. Kazakhstan’s court and arbitration system remains insufficiently developed for dispute resolution involving major Western companies and investors. The courts are inefficient and susceptible to political interference by a powerful presidency.

Moreover, the pending Russia-initiated Eurasian Union may further limit rule of law in Kazakhstan by subjugating it to new supranational institutions that would be dominated by Moscow.

The court system in Kazakhstan lacks sufficient capacity to protect property rights effectively. Infringements of intellectual property rights are rife. While recent changes in the anti-corruption law instituted mandatory asset forfeitures and broadened the definition of corruption to include fraud by government officials, corruption remains endemic, eroding the rule of law.

Although Kazakhstan has taken steps to crack down on corruption over the past few years, there are more robust measures to be taken by the government of President Nursultan Nazarbayev (in power since Kazakhstan’s independence in 1990). For instance, Kazakhstan ratified the United Nations Convention against Corruption in 2008, but events since then indicate that it still has a long way to go in creating a transparent and accountable government.

The February 2009 nationalization of BTA Bank, then the largest in Kazakhstan, was followed by a series of arrests on corruption charges.[6] In late 2011, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development issued a report on corruption in Kazakhstan that commended the country for ratifying the U.N. Convention Against Corruption and taking other steps to stifle corruption; but the report also indicated that Kazakhstan still has severe corruption problems, especially in the area of government procurement, and made numerous recommendations for fighting corruption.[7]

The incidents in December 2011—a series of protests by laid-off oil workers in Zhanaozen that turned deadly when police fired into the crowd—also cast a negative light on Kazakhstan’s extensive problems with corruption, inadequate and erratic law enforcement, and the rule of law unduly influenced by the powerful business interests and, at times, by the powerful executive branch. There are widely varying accounts by eyewitnesses of just how violent the demonstrators became and whether the use of lethal force in response was justified.[8]

In any case, the December 2011 incidents precipitated further demonstrations, which the government attempted to suppress by jailing protest leaders.[9] Although President Nazarbayev tried his best to distance himself from the whole debacle,[10] he did visit Zhanaozen and promised to set up new enterprises to create jobs in the community. Nazarbayev also fired several high-level officials, including his son-in-law, who was in charge of the sovereign wealth fund that manages the state oil company, and other executives of the state oil company. However, he has also cracked down on political opposition figures. Courts sentenced two of them to relatively light 15-day sentences (in response to later protests in Almaty), and two others are awaiting trial.[11]

Finally, the government needs to respond vigorously to the increasing challenges to the everyday security of individuals and companies from the rising threat of terrorism—some of which may be aimed at foreign corporate investors.

Limited Government. A new tax code in Kazakhstan went into effect on January 1, 2009, cutting the corporate tax from 30 percent to 20 percent, and lowering the value-added tax (VAT) from 13 percent to 12 percent. A withholding tax is levied at a rate of 20 percent on payments made to non-residents, and the VAT applies to import values, inclusive of customs and excise duties. Since January 1, 2011, personal income has been taxed on a progressive scale, instead of the previous flat 10 percent. Personal income tax will remain at 10 percent for those earning up to 250,000 tenge ($1,700) per month, but will rise to 15 percent for those earning 250,000 to 499,999 tenge, and to 20 percent for those earning 500,000 tenge and above.[12]

Overall, the burden of taxation on the economy amounts to 21.5 percent of total gross domestic product (GDP). Government spending is equivalent to 23.5 percent of GDP, creating a budget deficit of 2 percent of GDP. Substantial revenues from the state-owned oil company and other oil royalties received by the state, however, have allowed the government to bridge the funding gap between tax revenues and budgetary outlays, thus keeping the overall government budget balance positive; public debt stands at less than 15 percent of GDP.

As was the case with many other countries, Kazakhstan reacted to the global financial crisis in 2008 by priming the pump with government spending. Its stimulus packages have totaled $19 billion since 2007, amounting to 15 percent of annual GDP. Generally speaking, Kazakhstan has weathered the global crisis better than neighboring Uzbekistan, which is the second-largest economy in the region despite having twice the population of Kazakhstan and significant mineral resources. The difference is that Kazakhstan is comparatively much freer, having privatized much of its industrial sector much earlier and more extensively.[13]

The Kazakh government also passed a tax reform package that was due to take effect in 2012 but has now been pushed back to 2013 due to the continuing global economic turmoil. Changes in the tax code are designed to shift more of the fiscal burden to the mineral extraction sector, by increasing the mineral-extraction tax and further lowering the corporate rate to 15 percent.[14] Yet, unlike the taxation system, regulatory efficiency leaves much to be desired.

Regulatory Efficiency. Kazakhstan’s regulatory framework has undergone a series of reforms. The procedures to establish a business have been streamlined in recent years, although they remain costly and at times lack transparency. Labor regulations are applied relatively flexibly in practice, but the labor code as written continues to impose undue burdens and restrictions that can create obstacles for efficient business operations. Monetary stability is well maintained, but the government continues to exercise price-control measures.

The World Bank’s “Country Partnership Strategy” for Kazakhstan, issued on March 30, 2012, notes that the country’s progress is, in part, the result of significant “legislative changes—easing business entry and exit conditions, payment of taxes and protection of investors’ rights through strengthened corporate disclosure requirements—[that] improved the business climate, as did [earlier] improvements in insolvency procedures, concessions and competition legal frameworks as well as the licensing and inspection requirements,” but calls for the dismantling of remaining (and formidable) obstacles, such as “construction permits, access to financing, cross-border procedures, and licensing and permits.”[15]

KazMunaiGas Exploration and Production (KMG EP) is the state-owned national oil and gas exploration and production company. It functions as both the country’s second-largest oil-producing company (and as a joint venture partner with private international oil firms) as well as Kazakhstan’s supervisory regulator of the oil and gas industry. The World Bank noted in a 2011 report that, according “to the Fraser Institute’s global petroleum survey, private investors indicated that the level of regulatory uncertainty in Kazakhstan was a ‘mild deterrent to investment.’”[16]

Overall, the International Monetary Fund praised the government in August 2011 for managing and preserving the nation’s oil wealth “prudently” through “Kazakhstan’s stabilization fund—the National Fund of the Republic of Kazakhstan.”[17]

By making Kazakhstan’s business regulatory environment more consistent with global best practices there would also be positive spillover effects in areas such as competition law, transparency in privatization procedures, public procurement, and more adequate anti-corruption mechanisms.[18] These factors would improve Kazakhstan’s economic freedom and open the door for further foreign investment.

Open Markets. In 2010, exports reached $59.5 billion and imports amounted to $29.8 billion, on a balance-of-payments basis. Russia is still Kazakhstan’s main trading partner; it is the main source of imports and a leading market for exports. This is partly the result of Kazakhstan’s difficulty in moving up the value-added ladder, which makes it unable to compete in Western markets. Instead, the bulk of Kazakh exports to the West consist of raw materials, particularly oil and metals.[19]

The World Bank’s 2012 country strategy for Kazakhstan calls for the government to improve access to finance, which will be “essential for non-oil sector growth. Although bank liquidity is ample, non-performing loans (NPLs) remain high and constrain banks’ ability to provide fresh credit to the non-oil sector.”[20]

The trade-weighted average tariff rate is about 3 percent. Import licensing requirements, non-transparent standards, and customs inefficiency add to the cost of trade. Foreign investment is officially welcome, but favoritism toward Kazakh companies and inconsistent application of regulations are deterrents. Troubled banks have been recapitalized, and the financial sector is stable, yet capital markets remain underdeveloped.[21]

The Gold Rush. Kazakhstan is among the top 30 gold-producing countries in the world. Since physical gold is held by central banks around the world as an asset for its monetary value alone, countries that produce and export gold, such as Kazakhstan, face a unique set of challenges with regard to the potential of disequilibrium in its trade balance and current account.

As of January 1, 2012, the Kazakh central bank has declared a “priority right” over gold exports. Through this mechanism, the Central Bank of Kazakhstan reserves first priority in purchasing domestically produced gold, and only then sells the gold produced in Kazakhstan on the world market on behalf of a Kazakh producer. Thus, the Kazakh central bank exercises a prerogative to effectively purchase all in-country gold. If a Kazakh producer wants to sell gold to a foreigner, the central bank has the power to purchase that gold instead.[22]

In early 2012, Kazakhstan signed an agreement with Germany that gives the Germans access to its supply of rare earth metals in exchange for a variety of technology-sharing deals with German firms. (Siemens has contracted to renovate the Soviet-era railroad network.)[23]

Sovereign Wealth Fund and Kashagan Oil Field: A Case Study. Despite the strides Kazakhstan has made, there remains much room for improvement. Kazakhstan still has a high level of government involvement in the economy. A prime example (and which encompasses many of the Index of Economic Freedom indicators) is revealed by reviewing the recent history of Kazakhstan’s National Fund, which was created in August 2000 as a stabilization and investment mechanism.

“Samruk-Kazyna,” Kazakhstan’s National Welfare Fund (a state-owned “sovereign wealth fund”), maintains either complete or partial ownership of many important companies in the country. This includes the entirety of state oil and gas producer KazMunaiGas and uranium producer KazAtomProm. Samruk-Kazyna also owns the country’s more important airports, the Kazakhstan Electricity Grid Operating Company, and even has a 91 percent stake in the Kazakhstan Mortgage Company.[24]

Rather than allowing the free flow of capital, this sovereign wealth fund has created a situation where a state-controlled fund is dividing up capital investment. Capital is the lifeblood of innovation and entrepreneurship. The free market is far more effective than government at allocating capital.

The development of the giant Kashagan oil field is an example of another problem when it comes to investing in Kazakhstan: red tape and government intervention. The consortium developing the Kashagan oil field includes Eni, Royal Dutch Shell, ExxonMobil, Total, KazMunaiGas (each with a 16.81 percent stake), ConocoPhillips (8.4 percent), and Inpex Holdings (7.56 percent).[25] The Kashagan oil field was originally scheduled to begin production in 2005, but the date has continuously been pushed back.

In 2007, the government of Kazakhstan enacted a new law permitting it to revise or revoke natural-resource contracts deemed to be at cross-purposes with natural security. This allowed the government to increase the stake of state-owned KazMunaiGas in Kashagan, while decreasing that of its other major foreign shareholders. This was done unilaterally with little to no due process, and resulted in protests from Western governments.

The disagreement over Kashagan and other expropriation cases emphasizes the need for the rule of law, including professional independent courts in Kazakhstan. For example, it appears that the broad national security reach of the natural resources law contradicts private property protection clauses of the Kazakh constitution.

In order to have a truly free, business-friendly investment climate, rule of law and property rights must receive top policy priority. The Kazakh leadership needs to put a system in place that resolves legal issues quickly, effectively, impartially, and transparently, including enforcement of foreign arbitral awards in the country by Kazakh courts. The higher court in the country should opine on this matter.

Terrorism Could Threaten Open Markets. A new problem that foreign capital faces when entering Kazakhstan is that of terrorism. Kazakhstan had generally had a stable security environment devoid of militant extremism on the surface, but since Kazakhstan’s first suicide bombing in May 2011, several more violent acts have occurred. Foreign investors now fear for the safety of their capital assets, and wonder if Kazakhstan is still the relative safe haven it once was for their investments.[26]

According to Dr. Ariel Cohen of The Heritage Foundation,

Historically, the government of Kazakhstan has argued that there were few terrorists on its soil. This position, however, began to change in the early 2000s, driven by a growing appreciation of the asymmetric threat posed by terrorism and religious extremism to the security and stability of the Kazakh state…. Kazakhstan is not immune [to] internal threats, nor does it have a guarantee against regional extremist spillovers, as evidenced by ongoing volatility in the Fergana Valley and beyond. [27]

Kazakhstan’s security forces claim that they have the situation under control, but deeper international security partnerships would go a long way toward alleviating the doubts of corporations considering long-term investment in Kazakhstan. Improvements to Kazakhstan’s security environment will be particularly critical in 2014 and beyond, as U.S. troops leave Afghanistan, and Islamist terrorists will likely expand their scope of operations to include Central Asia.

Kazakhstan and Its Neighbors

The idea of a Eurasian Union was first suggested by Kazakhstan’s president, Nursultan Nazarbayev, shortly after dissolution of the Soviet bloc.[28] On May 15, 1992, Kazakhstan joined the Collective Security Treaty Organization, which serves as a mutual defense alliance between Russia, Belarus, Armenia, and the four Central Asian states except Turkmenistan. Two decades later, in his presidential campaign, Vladimir Putin raised the specter of a Russia-dominated supranational entity that will be built on the existing pillars of a common economic space, which includes former Soviet states.[29]

On November 18, 2011, the presidents of Russia, Kazakhstan, and Belarus signed an agreement for the establishment of a central integration body for the Eurasian Union—the Eurasian Economic Commission (EEC)—representing the three founding countries. The EEC is a supranational body led by Victor Khristenko, the former Russian vice premier, and aimed at integration coordination. It is responsible for the economic integration of the three founding states, as well as members joining in the future. However, Russia’s size, historic tradition, and military and economic power guarantee that the body will be Moscow-dominated. Already, 84 percent of the EEC’s 800-member staff are Russians.[30]

The leadership of what has been termed the Eurasian Union (EuU) claims that this integration will not affect the member states’ sovereignty. That claim is hard to believe, given Putin’s infamous pronouncement that the “collapse of the Soviet Union was the greatest geopolitical tragedy of our time.”[31]

The Kremlin sees the creation of the Eurasian Union as solidifying its grip on Russia’s “zone of privileged interests,” which is precisely the concern of many in the West and across Eurasia.[32]

In October 2011 Russia signed a free-trade agreement with a number of post-Soviet states including Ukraine, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Armenia, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, and Tajikistan.[33] Following in the footsteps of the EU, the next logical step would be to integrate a customs union, a unified economic union, and, finally, a common currency and politically integrated union—with Moscow at the helm.

Moscow’s plans do not sit well with the West, especially Europe, because of Russia’s dominant energy position. The Eurasian Union, if and when completed, could control up to 33 percent of the world’s natural gas reserves, magnifying the geopolitical power Russia already wields.[34]

These moves by Kazakhstan may entail significant and complicating ramifications for Kazakhstan’s future economic freedom score as well as its pending application to join the World Trade Organization.

Although there are short-term gains from the reversion to an inward-looking Eurasian economic sphere represented by the EuU, the experience of the former Warsaw Pact countries that are now EU members strongly suggests that remaining fully open to global trade has greater long-term benefits than remaining in the Russian orbit: increased productivity, ability to attract new FDI in sectors other than raw material extraction, and, through technology and management skills transfers, a more competitive and innovative Kazakhstan. Also, below-market energy prices are delaying long-overdue reform of the country’s inefficient and wasteful energy infrastructure.

Moreover, some observers predict that the Eurasian Union may fail because

Russia appears to be unable to prevent the erosion of its economic position in the post-Soviet space. Russia’s geopolitical competitors have managed to dramatically increase their strategic and economic footprints in the region. Most importantly, Russia seems to have lost its stranglehold over Turkmenistan’s vast gas reserves, with China increasingly becoming Ashgabat’s [the capital of Turkmenistan] principal trading partner.[35]

So, it is clear that not all states in the region want a place in the EuU. Countries endowed with their own valuable energy resources, such as Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, and Turkmenistan want to maintain their independence, and have the financial base to do so.

On the other hand, countries that depend heavily on Russia’s financial support, especially through mechanisms such as energy subsidies via preferential price agreements for natural gas, including Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, and Tajikistan, will have a hard time resisting the Kremlin’s call to follow in the footsteps of Belarus. Some countries will willingly buy into the Eurasian Union. Among these is Kyrgyzstan, which has already applied for membership. Economic dependence will also be used by Moscow as a tool to curb the more rebellious of its former vassals, such as Ukraine.

According to its founders, the Eurasian Union will be based on the principles and regulations of the WTO.[36] The Kazakh government’s website goes so far as to state that WTO accession and the creation of a Eurasian Union are parallel goals.[37] It is doubtful that such a union will lead to long-term progress in economic freedom. Future indexes may need to rate the freedom of the zone as a whole, as well as of its individual members.

As more countries participate in the Eurasian Union, Moscow’s intentions, and whether membership has a negative impact on economic freedom, will become clearer.

Uzbekistan’s Missed Opportunity. In 1991, experts expected Uzbekistan—which had a relatively well-developed agricultural sector, some manufacturing, and a larger urban population than Kazakhstan—to be the regional leader of the Central Asian countries, which were then leaving the dissolving Soviet Union. It was not to be. Kazakhstan’s oil wealth and its comprehensive economic development program allowed it to emerge as the economic leader in Eurasia. Kazakhstan currently has an average per capita income in excess of $11,000 a year, six times more than Uzbekistan’s. Uzbekistan President Islam Karimov has done the bare minimum to open his country to the West, and was uncomfortable doing even that. This attitude has landed Uzbekistan near the bottom of the 2012 Index of Economic Freedom—164th place of 179 countries ranked.

The most notable example of a foreign investment that was spoiled by lack of economic freedom in Uzbekistan is the story of Oxus Gold.[38] Oxus Gold had a joint venture in the Amantaytau Goldfields (AGF) with the Uzbek government. Oxus Gold had already agreed to sell its 50 percent stake in February 2011 to the government, when the Uzbek finance ministry started a hostile audit to find reasons to place AGF into liquidation.[39]

Expropriations such as this have happened before in Uzbekistan. However, in the AGF case, the Uzbek government went one step further. Said Ashurov, the chief metallurgist at AGF, was sentenced to 12 years in prison on a trumped-up espionage charge.[40] Such bullying tactics by the Uzbek government intimidate not just Oxus Gold, but other foreign investors, current and future. This behavior is certain to chase foreign investment from the country, and is a major reason why Uzbekistan is falling behind.

Even further behind is Uzbekistan’s neighbor, Turkmenistan, which currently ranks 168th in the Index of Economic Freedom, and has an average per capita income that is half of Kazakhstan’s. It should not be this way, since Turkmenistan boasts the sixth-largest natural gas reserves in the world.[41] Not only is the state heavily involved in key economic sectors, but partners in foreign investment are selected by the corrupt political system, which is especially damaging to Turkmenistan’s economy. The country’s vast oil and gas resources need serious investment if this Central Asian country is to realize its ambition of capturing growing world demand for energy, but that goal will not be realized under the current regime of cronyism and state capitalism.

To the east of Turkmenistan lies Tajikistan, a country that slipped from place 128 in the 2011 Index to place 129 in 2012. Tajikistan’s economy is plagued by an inefficient legal framework and by systemic corruption. Diplomatic cables released by WikiLeaks described the country as “President Emomali Rahmon’s corrupt, alcohol-sodden fiefdom.”[42] Tajik Aluminum Company, the most profitable factory in the country, is described by WikiLeaks as a cash cow for the president’s family. Sadly, these same U.S. diplomatic cables, written by career U.S. diplomat Ambassador Richard E. Hoagland, assert that the corrupt regime has no interest in true reform or economic growth, and that “President Rahmon prefers to control 90% of a $10 pie rather than 30% of $100 pie.”[43] Tajikistan is a prime example of a country whose leadership has no economic understanding or desire to reform.

Just 23 places behind Kazakhstan, ranked in 88th place overall in the 2012 Index Economic Freedom, is the Kyrgyz Republic, its impoverished southern neighbor. The country fell five places from 2011 to 2012, largely due to a significant retreat in property rights, mismanagement of public finance, and deterioration of business freedom (as measured by the World Bank’s annual “Doing Business” survey). Before April 2010, the Kyrgyz government had never expropriated any foreign-owned properties. Following the collapse of President Kurmanbek Bakiyev’s regime, however, the provisional government—without due process—nationalized a number of enterprises, companies, and properties that allegedly had ties to the former president’s son. On paper, the Kyrgyz Republic has a liberal investment regime. However, the legal concept of contract sanctity is not consistently observed.[44]

Mongolia, ranked 81st in the Index, is one of the 10 most-improved countries in 2012. Mongolia is currently enjoying one of the world’s greatest resource booms, and is poised to become one of the most radically transformed nations in human history. The rapidly growing mining sector is expected to triple the national economy by 2020 and to propel the country’s residents into the world’s middle class. How this industry boom is managed, and whether the property rights of foreign investors will be protected, however, will have a large impact on the country’s future development.[45]

Conclusion

Kazakhstan’s economic performance and development since its independence make it a regional leader and a top reformer. Yet, its Index of Economic Freedom track record suggests room for improvement. In particular, reducing government involvement in the economy; divesting from state ownership of national assets, including in the key natural resources and downstream energy sectors; fighting corruption; and boosting the rule of law are highly likely to attract foreign investment, increase GDP, and improve economic performance. Such a boost is expected to elevate Kazakhstan’s status to the upper strata of middle-income developing countries and facilitate the transition to a non-natural-resource-based economy.

Developing a well-thought-out and comprehensive program for such a reform, and its meticulous implementation, should be a top priority for Kazakhstan’s national leadership in this decade and the next. Its neighbors, likewise, should take notice and follow suit.

Equally important is a multi-sector program for improving national security and fighting Islamist extremism and terrorism. That, too, should remain a top priority, as security threats negatively affect investment, economic growth, and national morale. Far from being a police and security activity alone, such programs should also counter extremism through education, law enforcement and security services, and economic opportunities through increased economic freedom.