Why Free Trade is the Fairest Trade of All

“Free trade” should appeal to everyone. After all, it describes transactions between mutually willing parties. But if you’ve heard anything lately about free trade, it’s probably been bad. Critics tell us that it’s unfair to American workers and businesses, hurts our economy, exploits poor workers in the developing world, and harms the environment. A recent poll revealed that some 60 percent of Americans think our economic woes are at least partly due to free trade.[1] This public opinion encourages politicians to erect barriers to free trade, always in the name of something called “fair trade.”

Despite what we’re told, though, each of these indictments against free trade is false. There may be no subject on which public opinion and reality are so far apart. If you look at the evidence, it’s clear that American and foreign workers, our economy, and the environment are all better off to the degree that we enjoy free trade.

With Free Trade, We All Win

We’ve all heard the charges against free trade: “The rich get richer, the poor get poorer. Rich countries exploit the poor labor and weak regulations of poorer countries. The poor countries are poor because countries like the U.S. are rich.”

But the false assumption behind these charges is the “zero-sum game myth.” A zero-sum game is a win/lose game like chess, checkers, poker, badminton, and basketball. When the Celtics and the Bulls compete, for instance, if the Celtics are up, then the Bulls are down, and vice versa. The scales balance. It’s a zero-sum. Besides win/lose games (and lose/lose games, which no one wants to play), though, there are positive-sum or win/win games. In these games, some players may end up better off than others, but everyone ends up better off than they were at the beginning. No one simply loses.

An exchange in which both sides freely engage (i.e., in which no one is forced or tricked into participating) is a win/win, positive-sum scenario. Think about how this happens in everyday life. If you give your barber $10 for a haircut, presumably you’d rather have the haircut than the $10. And (unless you were holding your barber at gunpoint) presumably she’d rather have the $10 than the time and energy it takes to cut your hair. So you both see yourselves as better off as a result of the trade: It’s win/win.

FREE TRADE is an exchange of goods or services in which both sides of the trade freely engage without interference by the government or other parties. Neither party is prevented from trading, nor forced or tricked into trading.

Things Have Gotten Better, Not Worse

The benefits of free trade aren’t just theoretical. As international trade has expanded over the last 30 years, income per person and the average life expectancy have gone up in most countries, including those that are poor compared to the U.S. The exceptions have been countries with extremely corrupt and despotic governments and countries that have suffered civil war.

The exceptions have been countries with extremely corrupt and despotic governments and countries that have suffered civil war.

Worldwide, statistics on infant mortality, life expectancy, and poverty have improved in the last few decades.[2] In fact, the percentage of people living in absolute poverty—those with an income of less than $1 a day—has dropped since 1970. In 1970, the world population was 3.7 billion, and 38 percent (1.4 billion) lived below the absolute poverty line. By 1990, with a world population of 5.3 billion, the percentage languishing in absolute poverty dropped to 26 percent (still about 1.4 billion).[3] Although it is tragic that there are still people languishing in poverty, things have not gotten worse overall, even in the poor parts of the world. The rich may have gotten richer, but the lives of billions of the poor have improved as well.

What is Economic Freedom?

The Heritage Foundation’s annual Index of Economic Freedom defines policies that promote economic freedom as those that:

- Put the individual first and allow people to decide for themselves what is best for their own well-being and that of their families;

- Recognize that the free market is the only reliable predictor of the real prices of goods, labor, and capital;

- Use government to shape a fair and secure environment, protect private property and the value of money, enforce contracts, and promote competition, but not to produce or sell goods and services; and

- Emphasize openness to international trade and investment as the surest paths to increased productivity and economic growth.

How to Reduce Third-World Poverty

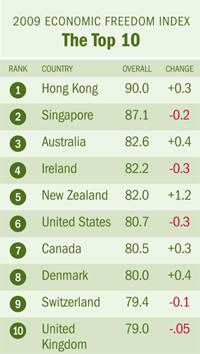

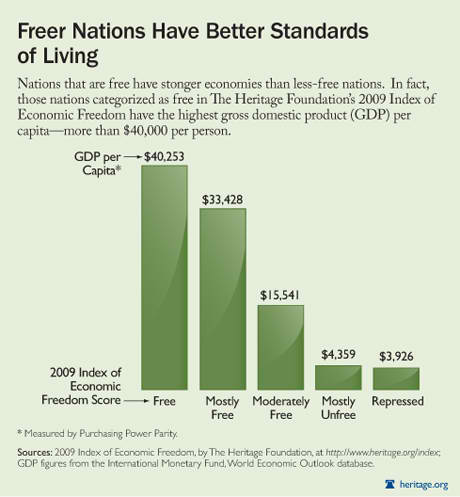

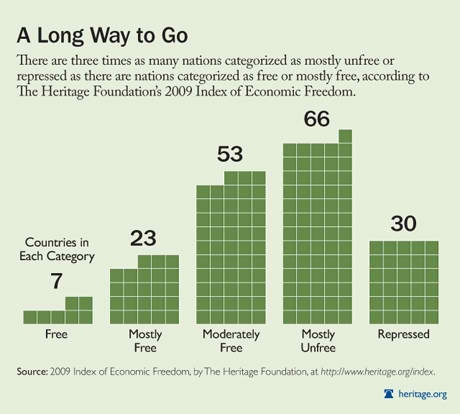

So what is the secret ingredient in the countries where conditions have improved? Economic freedom. The more economic freedom a country enjoys, the more it prospers over time. The annual Index of Economic Freedom, published by The Heritage Foundation and The Wall Street Journal shows this in considerable detail.[4] For fifteen years, the Index has charted the course of nations around the world as they have expanded or restricted their economic freedom.

The more economic freedom a country enjoys, the more it prospers over time. Economic freedom involves both the domestic and international policies of a country:

At Home: Rule of Law. Internally, a country should have a government that maintains the rule of law, protects private property, and safeguards financial exchanges like contracts and land titles. Rule of law prevents people from killing, stealing from, and defrauding one another.

At the same time, rule of law limits the power of government officials so that they don’t stray from their core responsibility to maintain order. Depending on how they wield their power, government officials can be either protectors or enemies of economic freedom. Rule of law creates the space in which individuals and groups are free to exchange goods and services according to their own choices. The vast network of those choices makes up the market.

International Policies. In international trade, domestic laws still do much of the regulatory work. An economically free country doesn’t “protect” (read: burden) itself with high barriers to trading with other countries. (We’ll talk much more about this below.) And, contrary to stereotype, trade among nations is not a free-for-all. When countries and their businesses are free trading partners, they enter into all manner of contracts and agreements with each other, which are typically dubbed with acronyms such as GATT, NAFTA, and WTO.[5] None of these agreements are perfect, but since countries enter them freely, they are not abandoning their sovereignty to transnational governments, but rather agreeing to rules so that, over the long haul, trade can benefit all parties.

International Policies. In international trade, domestic laws still do much of the regulatory work. An economically free country doesn’t “protect” (read: burden) itself with high barriers to trading with other countries. (We’ll talk much more about this below.) And, contrary to stereotype, trade among nations is not a free-for-all. When countries and their businesses are free trading partners, they enter into all manner of contracts and agreements with each other, which are typically dubbed with acronyms such as GATT, NAFTA, and WTO.[5] None of these agreements are perfect, but since countries enter them freely, they are not abandoning their sovereignty to transnational governments, but rather agreeing to rules so that, over the long haul, trade can benefit all parties.

Live Free and Prosper

A country enjoys “economic freedom” when its citizens are “free and entitled to work, produce, consume, and invest in any way they please under a rule of law, with their freedom at once both protected and respected by the state.”[6] In the Index’s ranking of the economic freedom of 179 countries, booming Hong Kong was number one on the list along with the United States and the United Kingdom not far behind. Burma, Cuba, and Iran were at the bottom of the list, and North Korea ranked as dead last.[7] In turn, as the charts below show, a nation’s prosperity is tied to its economic freedom. The countries that enjoyed the most economic freedom had per-person GDPs (gross domestic products) that were more than 10 times greater than those in countries with the least freedom.

However, despite its obvious benefits, economic freedom has proved hard to attain and maintain throughout the world. It’s easy to notice its absence when looking at a communist dictatorship or a corrupt and chaotic regime. Even in the U.S., economic freedom is under more subtle threat, usually from misguided policies.

“Fair Trade” Isn’t Fair

As a result of more than six decades of lowering barriers to free trade, the United States has become the central player in the global market, serving as a principle consumer and producer of goods and services flowing around the world. Trade now accounts for about one-third of our GDP, one measure of our economic well-being. This trade has bolstered U.S. investment, jobs, economic growth, and prosperity. At the same time, this trade has stimulated the economic growth (and its many ripple-effect benefits) of our trading partners.

On a local level, almost everyone understands the benefits of trade. For example, Dallas exchanges goods and services with other cities like Chicago, Los Angeles, and Poughkeepsie. As a result, Dallas enjoys greater prosperity by trading with these cities than if it confined trade within its city limits.

But a strange thing happens when we consider trade with other countries. In that larger arena, many come to view trading partners as opponents who must lose if we are to win, and vice versa. As a result, many believe that for America to get its share, our government must put its thumb on the scales of the international marketplace through so-called called “fair trade” policies.

The phrase “fair trade” is good rhetoric. After all, who would want “unfair trade?” The rhetoric, however, fails to square with the reality.

Tipping the Scales

One popular complaint about free trade is that it’s unfair to American workers. The argument goes like this: “Foreign workers will work for lower wages than their U.S. counterparts. Also, underdeveloped societies lack the same levels of environmental and labor regulations that American companies face. As a result, those societies have an unfair advantage and can charge lower prices for their goods.” This critique depicts a “race to the bottom” in which American workers must accept lower wages and fewer benefits to compete with low-cost labor and cheaper products of other countries, while American companies risk losing their sales to foreign competition.

Sometimes, foreign competition has driven American producers out of the marketplace; more often, however, U.S. firms have responded by becoming more competitive. After all, building a better mousetrap is ultimately better for everyone than keeping out competition from foreign mousetraps. The spur for improvement helps American workers and consumers alike. When workers become more productive, they can command higher wages. At the same time, consumers can purchase better products at lower prices. Thus, while some jobs may be lost when companies cannot meet the challenge of competition, the overall benefits of free trade to our economy greatly outweigh those isolated costs. Focusing on a very small aspect of the trade arena, proponents of so-called “fair trade” seek to block the natural forces of the market with “protectionist” policies to prop up uncompetitive U.S. firms.[8]

Protectionism: Long-Term Pain, Not Gain

Protectionism, which involves almost any government attempt to limit free trade with foreign traders, is always promoted for its benefits. The word itself sounds comforting. These policies are supposed to protect jobs, protect the environment, protect the American way of life, and even protect foreign workers. But the long-term impact of protectionism is the opposite of this rhetoric. Protectionist policies can take several forms: taxes on imports and exports, known as tariffs; quotas on the number or amount of goods like cars or steel, which indirectly drive up the price of imports by limiting supply; outright bans on trade; and all manner of labor and environmental regulations.

While politically well-connected industries or unions may enlist the government to give them a special advantage over their offshore competitors, America’s consumers, workers, and competitive firms ultimately pay the price. In the end, protecting one company or industry inevitably means harming other Americans. Tariffs on sugar may be an advantage for sugar producers in the U.S., for example, but they raise costs for every U.S. industry that uses sugar.

Tariffs increase the prices that American consumers pay for foreign imports. These price distortions change incentives in production, often enticing companies to move away from specializing in some goods and toward the protected goods, even if this means going outside the arena where their expertise could give them a comparative advantage. A company in the American South might be much better at growing hybrid corn than growing sugar cane, for instance; but it could end up growing sugar cane because high tariffs on foreign sugar make sugar artificially profitable for the company. So, even though its sugar cane operation is wasteful, it can charge much higher prices in the U.S. than it could in a free sugar market.

Limiting trade often places advanced-technology products and services beyond the reach of consumers, making them less productive as well. This happened to the French in the 19th century. At that time, British companies began to build better roads, along with faster horse-drawn coaches to make use of them. This made Britain much more productive because goods could be moved around much more quickly. The French government, however, chose to hinder new road construction in France and to limit the use of new, faster coaches on the bad roads it did have. As a result, France fell far behind Britain economically.[9]

Today, the promoters of “fair trade” often seek to impose tariffs or quotas if foreign governments do not establish more restrictive—and costly—labor and environmental regulations. For instance, they may push American-style child labor laws on countries where some child labor is needed for families to survive (as it was in the U.S. until a century ago). Forced out of legal jobs in, say, factories, children in such countries don’t suddenly enroll in private schools. They take less savory illegal jobs like prostitution.

Like other trade barriers, forcing regulations on other countries will harm everyone in the long run.

First, it will encourage our trading partners to retaliate by making it harder for the U.S. to trade our exports. In general, protectionist policies encourage trading partners to strike back with similar misguided policies. Many historians trace the severity of the Great Depression in part to such a “trade war.”[10]

When we focus on what we do best and then trade freely for everything else, everyone is better off.

Second, protectionist “fair trade” demands could be counterproductive. Historically, as a nation’s prosperity increases, so too does its ability to adopt labor and environmental regulations (see more on this below). Some of these regulations may be desirable but they come at a cost. Many of our trading partners are developing countries that can’t yet afford the cost. They are still struggling to create the institutions needed to build a healthy economy. Keeping them mired in poverty will do little to advance better labor and environmental standards.

Making the Most of Your Assets

Free trade benefits everyone because it allows partners to capitalize on their unique capacities and resources, what economists call their comparative advantage. Specialization of labor within a city or a country leads to greater prosperity for all. If each of us had to grow our own wheat, feed and milk our own cows, harvest cotton and loom it into fabric to make our clothing, build our own houses, and learn to do double bypass surgery, reattach retinas, or fill teeth, we would all be much worse off. Life would be nasty, brutish, and short. Instead, when we focus on what we do best and then trade freely for everything else, everyone is better off.

The same dynamic holds for the international arena. France, no doubt, has a comparative advantage over Norway in growing grapes and fermenting wine, while Norway has an advantage in North Atlantic fishing. Norwegians are probably better off buying much of their wine from France than trying to grow grapes and make all their wine themselves; and the French are probably better off buying cod from Norway.

In the long run, free trade is fair trade.

Free trade is fair when countries with different advantages trade and capitalize on those differences, rather than pretending they don’t exist. Access to capital, a highly skilled workforce, climate conditions, cultural heritage, and countless other things help determine what advantage one country has over another in the global marketplace. Attempts to equalize those differences in the name of “fairness” simply prevent countries from benefiting from free trade. In the long run, free trade is fair trade.

What About Fair Trade Coffee?

You may have noticed that when you buy a latte at, say, Starbucks, you have the option of buying more expensive “fair trade” coffee. With fair trade coffee, the coffee farmers are paid twice or more the market price (around $1.26 per pound in 2008), based on an estimate of how much they need to make a decent standard of living. That higher price, plus the costs of monitoring a “fair trade” supply chain, makes the coffee more expensive.

So what’s the problem with buying “fair trade” products, as long as it’s voluntary? Isn’t it just a market-oriented way to deliver charity?[11]

The problem is subtle. Paying artificially high prices for some coffee encourages poor farmers to enter or stay in the coffee market when it’s against their long-term advantage to do so.

Market prices for coffee have dropped in recent years because millions of people have started drinking different kinds of high-end coffee. As a result, more farmers and companies have entered the market around the world. Vietnam is now a major coffee exporter.[12] When the supply goes up, the price for coffee goes down, not because of injustice, but because of supply and demand. Some farmers who were competitive in 1990, however, are no longer competitive. There’s no law of economics or morality that sets the price of coffee high enough so that every coffee farmer everywhere will always be able to make a decent living growing coffee—anymore than there’s a law that everyone will always be able to make a decent living manufacturing tallow candles or eight-track tapes or Winnebagos.

While the market price for raw coffee will get more competitive, the artificially high “fair trade” prices are encouraging some farmers to enter and stay in quirky markets when they are not actually competitive. A dropping price tells producers and sellers that supply is exceeding demand, so they can adjust and reallocate scarce resources like time, land, and labor to more valued uses. A rising price signals the opposite. Farmers in fair trade schemes are deprived of this information. It’s in the long-term interest of some of farmers to start growing more competitive products or even to move out of agriculture altogether. Moreover, the small percentage of farmers in fair trade schemes are being favored arbitrarily over farmers in most places who don’t have access to such a scheme.

As it is, the future livelihood of farmers now benefiting from “fair trade” schemes depends on millions of people continuing to pay high “fair trade” prices. That’s a dangerous gamble since “fair trade” prices will rise with inflation, while the normal market price could stay the same or go down. (It’s at historic lows now.) This will shrink the demand for fair trade coffee. When the price gets high enough, many pious fair trade coffee drinkers will switch to regular coffee, or start drinking chai lattes instead. Then there will be way too many coffee farmers producing way too much “fair trade” coffee, which will devalue it even more.[13] How’s that fair?

Partially excerpted from Jay W. Richards, Money, Greed, and God: Why Capitalism is the Solution and Not the Problem (San Francisco: HarperOne, 2009).

The Myth of Outsourcing

American firms shackled by onerous labor and environmental regulations sometimes relocate to countries with less costly business environments. When they do, they are criticized for “outsourcing” American jobs and creating unemployment in the U.S. Free trade treaties such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) also are accused of encouraging such job losses because they do not allow taxes or tariffs to be imposed on outsourced goods.

Yet, in the words of University of Chicago professor Daniel W. Drezner, “Believing that offshore outsourcing causes unemployment is the economic equivalent of believing that the sun revolves around the earth: intuitively compelling but clearly wrong.”[14] In short, the problem is one of perspective (as is also the case with various other charges against free trade policies). From a long-range, large-scale perspective, these “outsourcing” specters disappear. Consider the realities of outsourcing:

1. Outsourcing is a minimal cause of job loss. It accounts for less than 1 percent of gross job turnover per year.[15] In fact, only 2 percent of job turnover in the U.S. is due to trade in general. Contrary to stereotype, the U.S. economy actually added 25 million jobs during NAFTA’s first 13 years, and U.S. manufacturing output rose 63 percent, compared with only 37 percent in the preceding period. Furthermore, compensation for manufacturing workers increased 1.6 percent annually, versus 0.9 percent in the preceding period.[16]

2. Outsourcing benefits the U.S. economy in the long run. According to reports issued in October 2007 by the Department of Commerce, the U.S. economy grew by 50 percent during NAFTA’s first 13 years.[17] Benefits from trade are estimated to amount to as much as $10,000 annually for a family of four.[18]

While it is true that companies relocating does lead to the loss of some jobs, the dynamism of a free economy, in which firms can move their operations across borders, ultimately makes that economy more prosperous and productive, leading to new and better jobs at home.[19]

This process is much like the effects of new technology. When new technologies appear, some jobs disappear. In particular, certain types of manufacturing jobs can become obsolete. But to view this as a net loss is to see the world economy as static rather than dynamic. In free economies, the jobs lost through technological advances are replaced by better, more productive jobs that develop from and use the new technology. For example, car factories replaced carriage and buggy whip factories. Computer chip fabricating plants, computer stores, and software companies replaced factories that produced typewriters and typing ribbon.

As more productive jobs replace obsolete jobs, the country’s standard of living rises not only because labor becomes more productive, but also by widespread use of the new technologies. To resist this trend by adopting protectionist measures means subsidizing less efficient producers—much like pumping taxpayer money into factories that produce eight-track tapes even after the CD has become obsolete. While eight-track tape manufacturers might favor this scheme, it’s foolish and wasteful. Elevated to the level of policy, such practices would ultimately harm the world economy, in which individuals would produce less and have less than they would if the market were free.

Free Trade Is Green

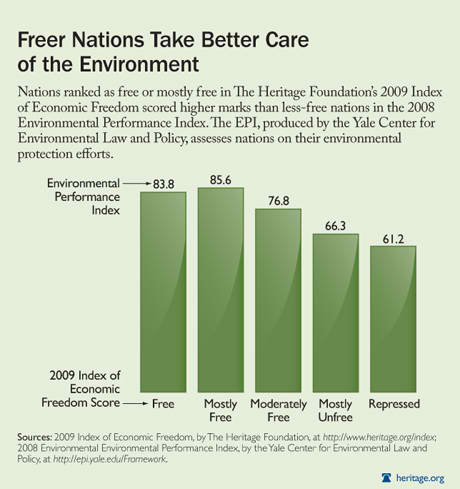

Free trade means that we do not force regulations on developing countries that have lower environmental standards than we impose on ourselves. Does that mean that free trade harms the environment?

The short answer is no. As mentioned above, saddling struggling countries with burdensome environmental regulations will, ultimately, be counterproductive. That’s because environmental protection is a costly good. Historically, we know that it becomes a priority only after a country achieves a certain level of prosperity. In other words, the poorer a trading partner is, the fewer resources it will have to comply with costly environmental policies and rules.

Conversely, the more a country prospers, the more likely it is to make the environment a priority: And it is free trade that engenders economic growth. As the chart on the previous page indicates, countries that enjoy the most economic freedom also have the best track record with regard to protecting the environment. Ironically, the burden of environmental regulations could ultimately stymie environmental protection in developing countries.

In addition, consider the likely effect of popular environmental regulations in industrialized nations, such as the costly “cap-and-trade” policies proposed in 2009 by Congress and the President to reduce carbon emissions in the United States. We already know that, economically, cap and trade would trigger a devastating surge in the price of energy and energy-intensive products (that is, just about everything, including the kitchen sink!).

What we don’t know is what the environmental benefits of such legislation will actually be, but we may glean some insight by looking at the effects of the Kyoto Protocol, a climate measure adopted by countries including Japan, Canada, and a number of Western European nations in 1997. Under this multilateral treaty, participating countries were to reduce their carbon emissions by 8 percent within a 10-year period. Ten years after signing on to the treaty, though, nearly every one of those countries had higher carbon dioxide emissions, with little sign that emissions will level off![20]

We should keep our markets open as a means to transfer clean technologies, keep international investment flowing, and promote economic growth and prosperity in the U.S. and around the world.

Rather than trying to coerce our environmental standards on other countries, we should keep our markets open as a means to transfer clean technologies, keep international investment flowing, and promote economic growth and prosperity in the U.S. and around the world. In the long run, open trade will not only be better for the world economy. It will also be better for the environment

A Long Way to Go

Despite the overwhelming benefits of free trade, in the United States, challenges to it multiply like bacteria in a warm Petri dish. To overcome those challenges, the U.S. should guard against high corporate tax rates, expensive and inefficient job training and re-training programs, costly and counterproductive regulations, and other misguided policies that undermine the competitiveness of American workers and firms. These burdens, not free trade, are the real threats to our nation’s economy.

Worldwide, the spread of economic freedom over the last 30 years has brought with it historic prosperity. Without it, billions fewer people would be alive today and billions more would experience a much lower standard of life. Yet billions still lack its benefits. Free trade won’t usher in utopia, of course; but over time, it is the best known way to reduce poverty and create wealth for entire nations.

To read more on these topics, see:

- The Heritage Foundation’s 2009 Index of Economic Freedom, at http://www.heritage.org/index/.

- Daniella Markheim, “Free Trade: The Fairest Trade for America,” Heritage Foundation WebMemo No. 2169, December 12, 2008, at http://www.heritage.org/Research/tradeandeconomicfreedom/wm2169.cfm.

- Daniella Markheim, “An Act to End Trade,” Heritage Foundation WebMemo No. 2524, July 6, 2009, at http://www.heritage.org/Research/tradeandeconomicfreedom/wm2524.cfm.

- Daniella Markheim, “Climate Policy: Free Trade Promotes a Cleaner Environment,” Heritage Foundation WebMemo No. 2408, April 29, 2009, at http://www.heritage.org/Research/tradeandeconomicfreedom/wm2408.cfm.

- Daniella Markheim and Terry Miller, “Trade Liberalization Continuing Despite Doha Impasse,” Heritage Foundation WebMemo No. 2187, September 19, 2008, at http://www.heritage.org/Research/tradeandeconomicfreedom/bg2187.cfm.

- Terry Miller, “Productivity Growth, Not Trade, Is Cutting Manufacturing Jobs,” Heritage Foundation WebMemo No. 1709, November 7, 2007, at http://www.heritage.org/Research/Economy/wm1709.cfm.

- Tim Kane, Brett D. Schaefer, and Alison Acosta Fraser, “Myths and Realities: The False Crisis of Outsourcing,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 1757, May 14, 2004, at http://www.heritage.org/Research/Economy/bg1757.cfm.

- Jay W. Richards, Money, Greed, and God: Why Capitalism is the Solution and Not the Problem (San Francisco: HarperOne, 2009), chapter 4.