U.S. Army

Thomas W. Spoehr

The U.S. Army is America’s primary agent for the conduct of land warfare. Although it is capable of all types of operations across the range of military operations and support to civil authorities, its chief value to the nation is its ability to defeat and destroy enemy land forces in battle.

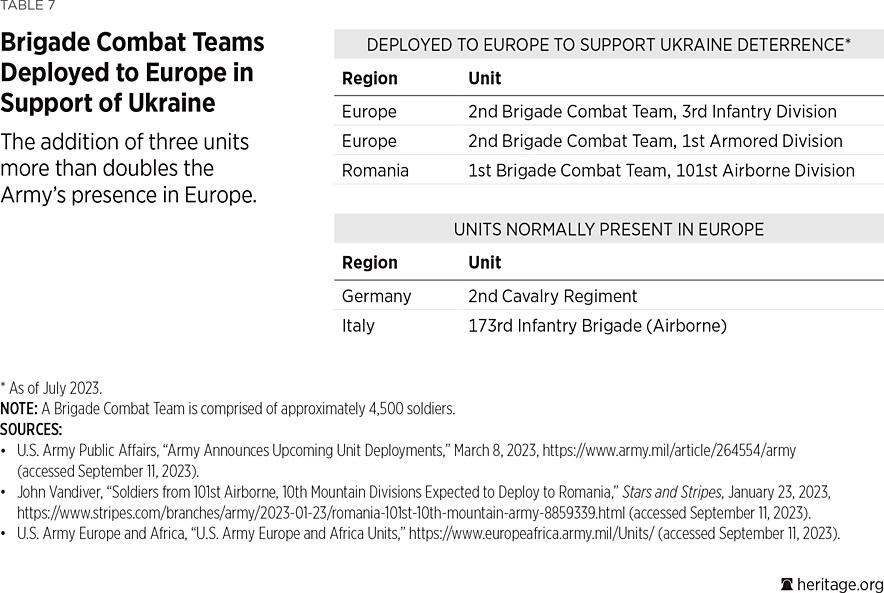

The Army is engaged throughout the world in protecting and advancing U.S. interests. As of April 19, 2023, the Army had “137,000 soldiers in over 140 countries” supporting America’s security interests.1 Most notably, it has deployed significant forces to NATO countries as a deterrent to further aggression by Russia. As of May 2, 2023, 43,000 soldiers were deployed to Europe bolstering NATO and demonstrating U.S. commitment to the region.2

On May 2, 2023, speaking of the deployments to Europe, Secretary of the Army Christine Wormuth and then-Army Chief of Staff General James C. McConville testified that:

In Poland, the Army has forward-stationed the V Corps Headquarters Forward Command Post—the first permanent U.S. forces on NATO’s eastern flank. We are maintaining a substantial rotational force in Poland, including an Armored Brigade Combat Team (ABCT), combat aviation brigade, and a division headquarters. In Romania, we have headquartered a rotational brigade combat team, supporting an additional maneuver force on the eastern flank. In the Baltics, we have enhanced our rotational deployments—which include armored, aviation, air defense, and special operations forces—to reinforce Baltic security, enhance interoperability, and demonstrate the flexibility and combat readiness of U.S. forces.3

The Army, like the other military services, finds itself under extraordinary operational and financial pressure. In some cases, advances in firepower like ballistic and cruise missiles, electronic warfare capabilities, and loitering munitions delivered by drones fielded by adversaries like China, Russia, and Iran have outpaced the U.S. Army’s capabilities. Information-age warfare requires new levels of speed and precision in Army sensor-to-shooter chains. Autonomy is changing the character of warfare, and the Army has developed some bold ideas about how to take advantage of this technology, but today they are aspirational.

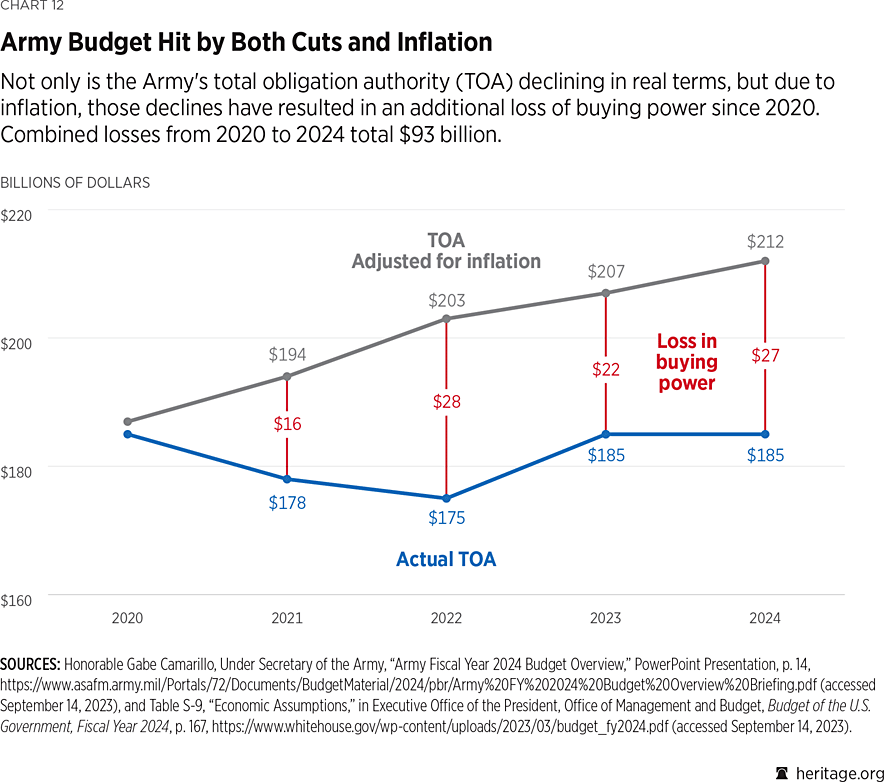

In her initial message to the Army, Secretary Wormuth set out six objectives. The first and arguably most important is to “put the Army on a sustainable strategic path amidst this uncertainty.” Wormuth acknowledged that the Army is “facing increased fiscal pressures,” and while the objective of “a sustainable strategic path” is noble and well-founded, it is not at all clear how the Army will be able to find such a path given its significant and continuing year-over-year losses in buying power.4

When official inflation is factored in, the Army has cumulatively lost over $74 billion in buying power from fiscal year (FY) 2019 to the President’s Budget Request for FY 2024. If Army budgets since 2019 had merely kept up with inflation, the request for FY 2024 would have been $210.9 billion. Instead, the requested budget was $185.5 billion.5 Signs of budget strain are clearly visible in the Army’s proposal to cut large procurement programs such as Paladin Integrated Management (PIM) (reduced by $211 million from FY 2023); Stryker upgrades (reduced by $277 million from FY 2023); and Abrams tank upgrades (reduced by $549 million from FY 2023).6

Arguments are being made that America no longer needs a strong modern Army because, for example, China is largely a maritime threat, but such arguments ignore history.7 We need to look no further than the ongoing war in Europe between Russia and Ukraine to remember that capable land power is an enduring need for the United States.

America has a horrible record of predicting where it will fight its next war. As former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates famously said:

When it comes to predicting the nature and location of our next military engagements, since Vietnam, our record has been perfect. We have never once gotten it right, from the Mayaguez to Grenada, Panama, Somalia, the Balkans, Haiti, Kuwait, Iraq, and more—we had no idea a year before any of these missions that we would be so engaged.8

America should not be willing to gamble that the next conflict will be in the Indo-Pacific and put all our eggs in one basket—largely naval—and ignore the continuing need for land power that would be essential in many regions and contexts. Many overlook the fact that great-power competition with China and Russia is a global contest, which means that we face the enduring need to counter aggression wherever it may occur, not just within the territory or waters of China or Russia. All of this reinforces the reality that America has a long-term need for modernized, sufficiently sized land power.

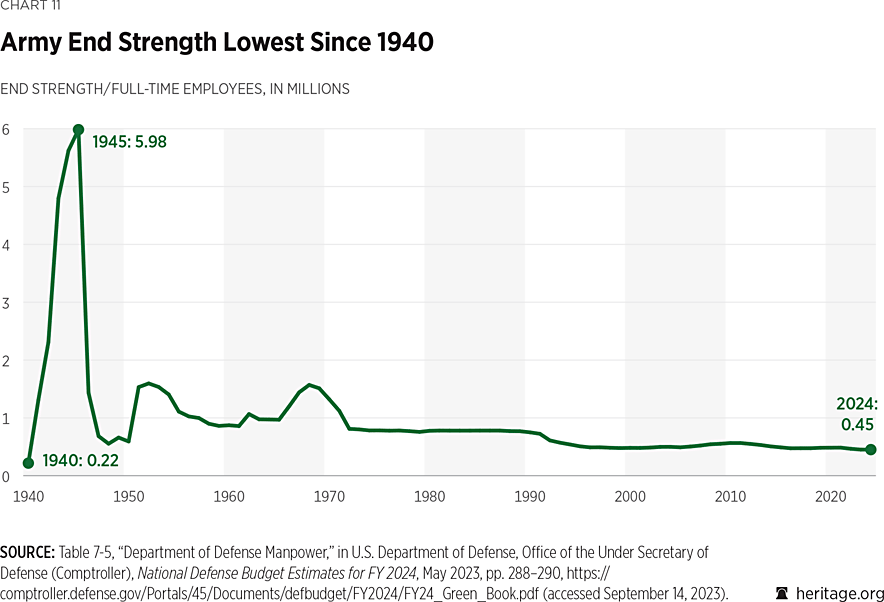

An Army Recruiting Crisis. In its FY 2023 budget request, the Army asked for and received a cut of 12,000 in its Regular Army end strength from 485,000 to 473,000. Later in 2023, based on a rapidly deteriorating recruiting forecast, the Army requested that its end strength be lowered by an additional 21,000 to 452,000 for a total of 33,000 compared to its original request for that year. This extraordinary move reflects the dire nature of the recruiting crisis facing both the Army and, to a degree, the other services as well.9 Pentagon leaders testified in April 2023 that “[t]he Army, Navy, and Air Force will not make enlistment goals this year.”10

The Army is facing a recruiting crisis the likes of which it has not experienced since the transition to the All-Volunteer Force in 1973.11 Since 2018, the Army has been missing its recruiting goals and making up the difference with strong numbers of reenlistments. Now facing extraordinary financial pressure and in order to save money, it has been forced to face reality and cut spaces for servicemembers that it does not anticipate being able to recruit. The reasons for this crisis are many.

- The percentage of Americans that qualify for military service without a waiver dropped from 29 percent in 2017 to 23 percent in 2022.

- The predominant factor in disqualification is obesity.12

- Low unemployment makes recruiting difficult, and as this book was being prepared, the U.S. unemployment rate was 3.5 percent.13

- Finally, for a variety of reasons that are beyond the scope of this study, fewer Americans are expressing a desire to serve in the armed forces.14

The results of this recruiting crisis include lower manning in Army formations, critical shortages in certain career fields, and lower overall readiness. If the crisis is not ameliorated, its longer-term implications are even more consequential.

Chronic Underfunding. The U.S. Army is currently the world’s most powerful army in terms of the equipment it uses and the combat effectiveness of its formations, but it is also too small and insufficiently modern to meet even the modest requirements of the 2022 National Defense Strategy (NDS),15 much less to handle two major regional contingencies (MRCs) simultaneously, which many experts believe is necessary.16

Even though the conflict in Iraq has ended and the military was withdrawn from Afghanistan, the Army’s focus on counterinsurgency during the period from 2001 to 2016 essentially precluded the service from modernizing the key combat capabilities that it needs now for near-peer competition. In 2011, for example, the Army cancelled its only mid-tier air defense program, the Surface Launched Advanced Medium-Range Air-to-Air Missile (SLAMRAAM), based on its assessment that it would not face a threat from the air in the foreseeable future.17 In 2022, the Army contracted to buy from Norway largely the same system, the National Advanced Surface-to-Air Missile System (NASAMS), that it cancelled in 2011, now to support Ukraine.18

The Army’s last major modernization efforts occurred in the 1980s with the fielding of the M-1 Abrams Tank, the M-2 Bradley Fighting Vehicle, and the Blackhawk and Apache helicopters. As General McConville has cogently argued, “the Army is changing to meet our future challenges. These changes cannot happen through incremental improvements. We must transform the Army, and the time is now.”19 This implies a modernization effort contemporary with the current threat environment rather than that of the Cold War and an updating of warfighting concepts not rooted in the Cold War but developed and experienced during nearly two decades of counterinsurgency operations.

The Army’s ability to transition from counterinsurgency operations was further constrained by a period of fiscal austerity that began with the Budget Control Act (BCA) of 2011 and lasted for ten years.20 The inability to fund what was needed led to difficult across-the-board trade-offs in equipment, manpower, and operations accounts. Downward budget pressure drove the Department of Defense (DOD) in 2014 to consider cutting the Army’s Active component end strength from more than 500,000 to 420,000. If implemented, this would have resulted in “the smallest number of troops since before the Second World War.”21 Multiple equipment modernization programs were cancelled.

The change of Administrations in 2017 forestalled those cuts in end strength. However, the addition of billions of dollars by Congress and the Trump Administration, while it served to arrest the decline of the Army and significantly improve unit readiness, was not sufficient to modernize or significantly increase the size of the force.22

Uncertain Strategic Direction. The Biden Administration’s National Security Strategy, published in October 2022, was strangely silent on the topic of military force; in fact, the U.S. Army does not appear at all in the document. The National Defense Strategy similarly contains little useful guidance with respect to the Administration’s views on the Army and its role in defending U.S. national interests.23 As but one consequence, this absence of clarity in mission, prioritization, and even value as they related to land power has not helped the Army to make a compelling case for programs, capacity, and focus.

Loss of Buying Power. Despite relatively broad agreement that the DOD budget needed real growth of 3 percent to 5 percent to avoid a strategy–budget mismatch,24 the Army budget topline did not meet that target in FY 2019 and has not done so since.

Of all the services, the Army has fared the worst in terms of resources. Its funding levels plateaued with the FY 2020 budget and since then have declined in constant dollars. The Army received approximately $181 billion in FY 2019, $186 billion in FY 2020, $177 billion in FY 2021, $185 billion in FY 2022, and $185 billion for FY 2023 and requested approximately $185 billion for FY 2024, amounting to a relatively flat budget over the past half-decade while the costs of manpower, matériel, and energy have increased.25

Testifying before the House Appropriations Committee’s Subcommittee on Tactical Air and Land Forces in April 2023, Lieutenant General Erik Peterson, Army Deputy Chief of Staff for Programs, summarized the situation in starkly candid terms:

Several years of ruthless prioritization, eliminating, reducing and deferring lower priority and less necessary efforts, as well as divesting of legacy capabilities, has left little flexibility in our topline. We made the easy choices the first couple of years of this effort. We’re now well into the realm of hard choices, really hard choices and downright excruciating choices.26

General McConville’s more than $1.9 billion Unfunded Priority List for FY 2024, containing dozens of critical items, is testament to what the Army was not able to include in its budget request: air defense systems, organic industrial base modernization, and helicopter replacement—among many other programs.27

Capacity

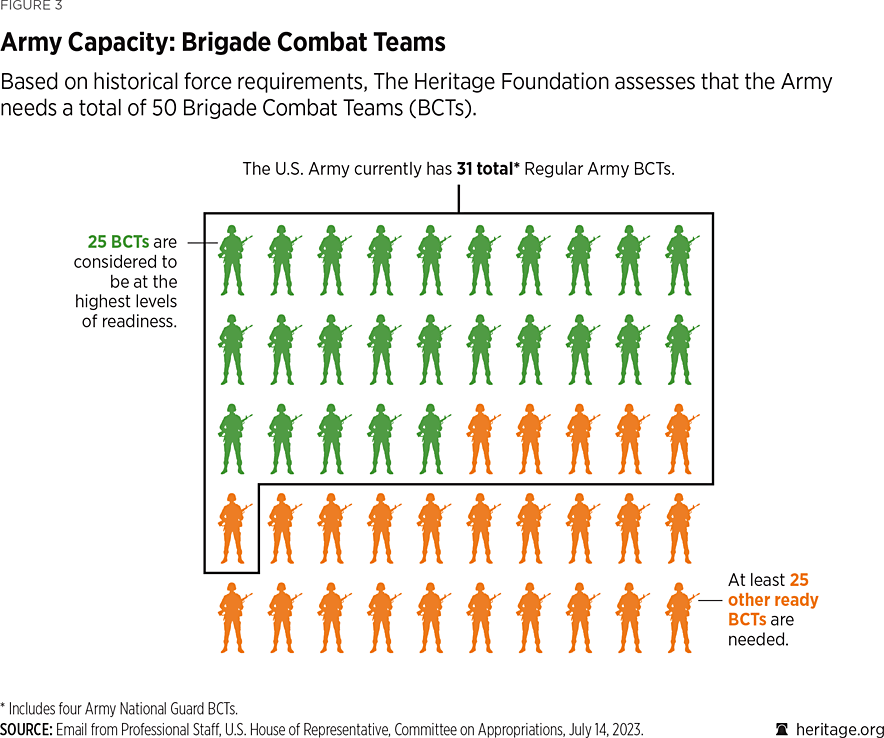

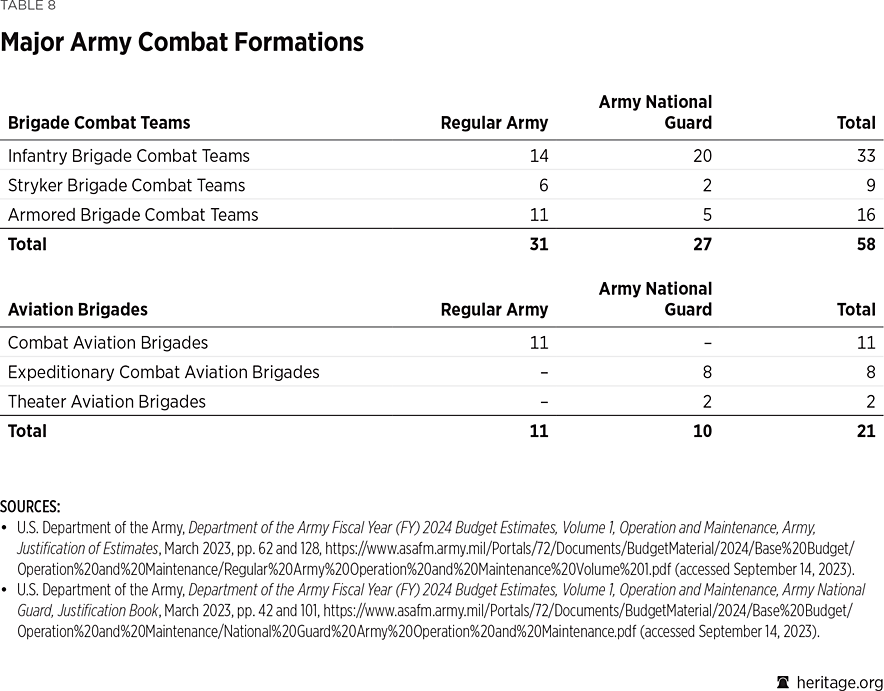

Capacity refers to the sufficiency of forces and equipment needed to execute the National Defense Strategy. One of the ways the Army quantifies its warfighting capacity is by its number of Brigade Combat Teams (BCTs).

Brigade Combat Teams. BCTs are the Army’s primary combined arms, close combat force. They often operate as part of a division or joint task force, both of which are the basic building blocks for employment of Army combat forces. BCTs are usually employed within a larger framework of U.S. land operations but are equipped and organized so that they can conduct limited independent operations as circumstances demand.28

BCTs range between 4,000 and 4,700 soldiers in size. There are three types: Infantry, Armored, and Stryker. At its core, each of these formations has three maneuver battalions enabled by multiple other units such as artillery, engineers, reconnaissance, logistics, and signal units.29

The simplest way to understand the status of hard Army combat power is to know the readiness, quantity, and modernization level of BCTs. This section deals with the number of BCTs in the force.

In 2013, the Army announced that because of end strength reductions and the priorities of the prior Administration, the number of Regular Army BCTs would be reduced from 45 to 33.30 Subsequent reductions reduced the number of Regular Army BCTs from 33 to 31, where they remain today.31

When the Trump Administration and Congress reversed the planned drawdown in Army end strength and authorized personnel growth beginning in 2018, instead of “re-growing” the numbers of BCTs, the Army chose to “thicken” the force and raise the manning levels within the individual BCTs to increase unit readiness. The Army’s goal was to fill operational units to 105 percent of their authorized manning,32 but the decision announced in the FY 2023 budget to cut end strength by 33,000 soldiers (to 452,000) will reverse those trends and cause units to be undermanned instead of overmanned.

Combat Aviation Brigades. The Regular Army also has a separate air component that is organized into Combat Aviation Brigades (CABs). CABs are made up of Army rotorcraft, such as the AH-64 Apache, and perform various roles including attack, reconnaissance, and assault. The number of Army aviation units also has been reduced. There are now 11 CABs in the Regular Army.33

Generating Force. CABs and Stryker, Infantry, and Armored BCTs make up the Army’s main combat fighting forces, but they obviously do not make up the entirety of the Army. Assuming that the Army shrank proportionately in all categories as it reduced to 452,000 in the Active component, there are approximately 194,000 soldiers in combat units, 123,000 in support units, and 134,000 in overhead units. Overhead is composed of administrative units and units that provide such types of support as preparing and training troops for deployments, carrying out key logistics tasks, staffing headquarters, and overseeing military schools and Army educational institutions.34

Functional or Multifunctional Support Brigades. In addition to the institutional Army, a number of functional or multifunctional support brigades provide air defense; engineering; explosive ordnance disposal; chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear protection; military police; military intelligence; and medical support among other types of battlefield support. Special operations forces such as the 75th Ranger Regiment, six Special Forces Groups, and the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment are also included in these numbers.

The Army is revising its force structure to accommodate a lower active end strength. When its end strength was reduced from 485,000 to 452,000 in FY 2023, the Army did not announce any changes in force structure. This has resulted in understrength units. Among other changes, the Army is reportedly considering a 10 percent cut in Special Forces structure.35 Other changes are likely.

New Concepts and Supporting Force Structure. At the same time the Army is facing the need to cut units to meet its new end strength, it is also trying to adapt its force structure to meet the anticipated new demands of near-peer competition. The foundations for these changes are contained in the Army’s Multi-Domain Operations (MDO) concept, published in December 2018, which describes how the Army views the future.36

In January 2022, the Army announced that it planned to modify its force structure for MDO under the designation “Army 2030.” Other than that announcement, the Army has been silent on future force structure and its plans are seemingly in flux as it grapples with recruiting shortfalls. As part of its adaptation to MDO, the Army did reactivate V Corps Headquarters on October 16, 2020, to provide operational planning, mission command, and oversight of rotational forces in Europe.37 On June 8, 2022, the Army reactivated the 11th Airborne Division in Alaska as an element of its “arctic strategy.”38

The Army also has announced plans to create five Multi-Domain Task Forces (MDTFs): “theater-level maneuver elements designed to synchronize precision effects and precision fires in all domains against adversary anti-access/ area denial (A2/AD) networks in all domains, enabling joint forces to execute their operational plan (OPLAN)-directed roles.”39 One MDTF is currently stationed at Joint Base Lewis–McChord in Washington State. The second is stationed in Wiesbaden, Germany, aligned to Europe,40 and the third was activated on September 23, 2022, in Hawaii.41 These task forces contain rockets, missiles, military intelligence, and other capabilities that will allow Army forces to operate seamlessly with joint partners and conduct multi-domain operations. The Army has not announced plans for the remaining two of the five MDTFs that were originally envisioned.

To relieve the stress on the use of BCTs for advisory missions, the Army has activated six Security Force Assistance Brigades (SFABs), one in the National Guard and the other five in the Regular Army. These units, each one of which is composed of 816 soldiers, are designed specifically to train, advise, and mentor other partner-nation military units. The Army had been using BCTs for this mission, but because train-and-assist missions typically require senior officers and noncommissioned officers, a BCT comprised predominantly of junior soldiers was a poor fit. Other than the National Guard SFAB, the five active SFABs are regionally aligned to combatant commands.42

Force Too Small to Execute the NDS. Army leaders have consistently stated that the Army is too small to execute the National Defense Strategy at less than significant risk. For FY 2023, the Army had an authorized total end strength of 1,010,500 soldiers:

- 452,000 in the Regular Army,

- 177,000 in the Army Reserve, and

- 325,000 in the Army National Guard (ARNG).43

In March 2021, General McConville stated that “I would have a bigger…sized Army if I thought we could afford it, I think we need it, I really do…. I think the regular Army should be somewhere around 540–550 [thousand],” and “we’re sitting right now at 485,000.” (Of course, the Army is “sitting” now at 452,000.) He further observed that “I’ve probably already had to give up the growth that we’re going to have planned” and that “[w]e’re probably not going to grow the Army even though I’d like to, more, because end strength is something we have to take a look at.”44

The Army’s prior plans to increase the size of the Regular Army force were slammed into reverse because of recruiting challenges. The Army had planned to raise the Regular Army incrementally to above 500,000 by adding approximately 2,000 soldiers per year.45 At that rate, it would have reached 500,000 by around 2028. Now that modest plan is off the table.46

Overall end strength dictates how many BCTs the Army can form, and by cutting end strength, the service not only will be unable to add more combat units or other in-demand units such as air and missile defense units, but also will have to reduce the manning levels in the units it possesses. This will drive a higher operational tempo (OPTEMPO) for Army units and increase risk both for the force and for the Army’s ability to carry out its mission.

Many outside experts agree that the U.S. Army is too small. In 2017, Congress established the National Defense Strategy Commission to provide an “independent, non-partisan review of the 2018 National Defense Strategy.” (Two of the commissioners, Dr. Kathleen Hicks and Mr. Michael McCord, are now top DOD leaders.) Among its findings, the commission unanimously reported that the NDS now charges the military with facing “five credible challengers, including two major-power competitors, and three distinctly different geographic and operational environments.” The commission assessed that “[t]his being the case, a two-war force sizing construct makes more strategic sense today than at any previous point in the post-Cold War era.” In other words, “[s]imply put, the United States needs a larger force than it has today if it is to meet the objectives of the strategy.”47

In addition to the increased strategic risk of not being able to execute the NDS within the desired time frame, the combination of an insufficient number of BCTs and a lower-than-required Army end strength has resulted in a higher-than-desired level of OPTEMPO. Assistant Deputy Chief of Staff, G-3/5/7, Major General Sean Swindell recently stated that the Army had tried to reduce the demands on the force but that this “effort has been going in the opposite direction.”48

Army Force Posture. The Army also has transitioned from a force with a third of its strength typically stationed overseas, as it was during the Cold War, to a force that is based mostly in the continental United States. An average of 311,870 troops were stationed in Europe from 1986 to 1990, and the majority were Army soldiers. When the Berlin Wall fell, that number plunged to 109,452 from 1996–2000,49 and the numbers have continued to drop. In 2023, only two BCTs are permanently stationed overseas: the 173rd Airborne BCT in Italy and the 2nd Cavalry Regiment in Germany. The desire to find a “peace dividend” following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, combined with a reluctance to close bases in the United States, led to large-scale base closures and force reductions overseas. Even though the 2022 NDS places a high premium on how the Joint Force is postured, most of the Army remains in the U.S., thousands of miles from where it will be needed.

Among Army units that deploy periodically are Armored and Stryker Brigade Combat Teams (ABCTs) and Patriot Battalions that rotate to and from Europe, Kuwait, and Korea. Rather than relying on forward-stationed BCTs, the Army currently rotates ABCTs to Europe and Kuwait and Stryker BCTs to Korea on a “heel-to-toe” basis so that there is never a gap.

The Russia–Ukraine war has brought the question of stationing more Army forces in Europe back to the forefront. Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman General Mark Milley has suggested that the U.S. should establish more permanent European bases and rotate more forces to the continent.50 There is disagreement as to which represents the better option: rotated forces or forward-stationed forces.

- Proponents of rotational BCTs argue that they arrive fully trained, that they remain at a high state of readiness throughout their typically nine-month overseas rotation, and that the cost of providing for accompanying military families is avoided.

- Those who favor forward-stationed forces point to a lower overall cost (when their equipment remains in place), forces that typically are more familiar with the operating environment, and a more reassuring presence for our allies.51

In reality, both types of force postures are needed, not only for the reasons mentioned, but also because the mechanisms by which a unit is deployed, received into theater, and integrated with the force stationed abroad should be practiced on a regular basis.

Capability

Capability in this context refers to the quality, performance, suitability, and age of the Army’s various types of combat equipment. In general, the Army is using equipment developed in the 1970s, fielded in the 1980s, and incrementally upgraded since then. This “modernization gap” was caused by several factors: the predominant focus on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan since 9/11; pressures caused by budget cuts, especially those associated with the BCA; and failures in major modernization programs like the Future Combat System, Ground Combat Vehicle, and Crusader artillery system.

Army leaders today clearly view this situation as a serious challenge. General James Rainey, the head of Army Futures Command, has said that “[w]e need to approach 2040 with a sense of urgency now” because “[t]ransforming the Army to ensure war-winning future readiness…is the best guarantee that our successful materiel modernization efforts will produce lethal formations that will deter our enemies, and, if required, dominate the land domain in conflict.”52

General McConville has similarly urged that “[w]e must transform the Army” and that “the time is now…to transform our doctrine, our organizations, our training…our equipment, and…how we compete around the world in order to protect the freedoms and the global order we enjoy today.” He further suggests “that about every 40 years, the Army transforms to meet the National Security threats of that time. We did it in 1940’s for World War II; we did it in 1980’s for the Cold War; we are doing it now in 2020 for the Great Power Competition environment that we live in.”53

The Army has embarked on an ambitious program to modernize and hopes to put 24 new systems into the hands of soldiers in FY 2023. Among these systems are hypersonic missiles, a precision strike missile, a directed energy air defense capability, and the Lower Tier Air and Missile Defense Sensor. These systems represent tangible progress.

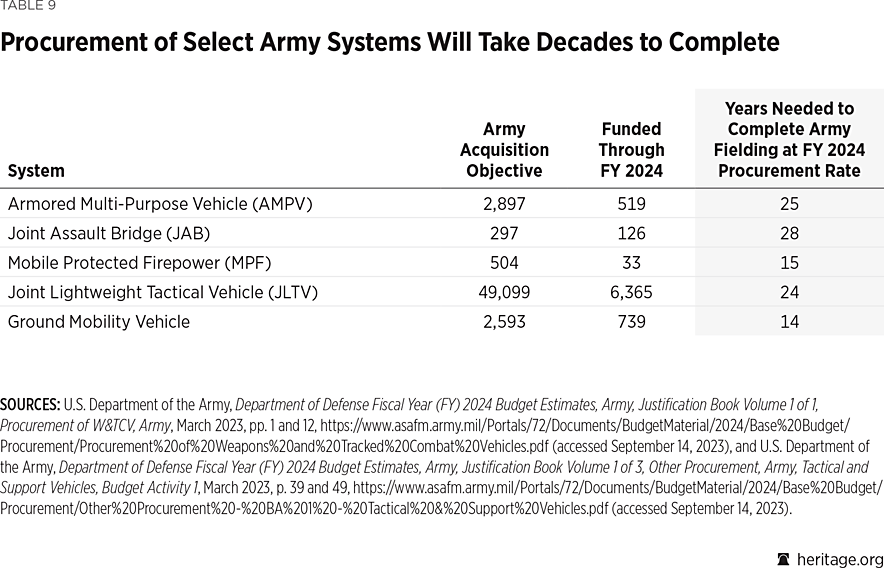

Interested parties also should pay attention to additional areas other than the number of systems being fielded: the quantities of the systems being fielded and the times that will be required for the Army to reach their acquisition objectives for new equipment. Because of budget limitations, the initial quantities of systems being fielded are relatively modest: for example, 120 Precision Strike Missiles. Reaching the acquisition objective for other pieces of new equipment will take many years: for the Armored Multipurpose Vehicle, 25 years; the Joint Lightweight Tactical Vehicle, 23 years, and Mobile Protected Firepower, 14 years.54

Loss of Competitive Advantage. These new modernization programs cannot come quickly enough. As an example of how Army equipment is falling behind that of our competitors, the Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS), first introduced in 1991, is the Army’s only ground-launched precision missile with a range greater than 100 kilometers (km). Because of restrictions in the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces Treaty and other factors, it was limited to a maximum range of 300 km.

China and Russia have much more substantial inventories of conventional, precision, ground-launched missiles and rockets. China has nine major ground-launched missile systems and more than 425 launchers. These capable systems can range from 600 km (DF-11A and DF-15) to 4,000 km (DF-26).55 Russia, on the other hand, at least before the war in Ukraine, had the widest inventory of missiles in the world: at least four conventional ground-launched missile systems that can range from 120 km (SS-21) to 2,500 km (SSC-8).56 The Army plans to start fielding the Precision Strike Missile in the fourth quarter of 2023, but the initial quantities will be modest (120).57

Another example of this loss in competitive advantage can be found in main battle tanks. When the M-1 Abrams was introduced in 1980, it was indisputably the world’s best tank. Since then, Russia has developed—and before the Ukraine War was reportedly prepared to export—versions of its T-14 Armata tank, which has an unmanned turret, reinforced frontal armor, an information management system that controls all elements of the tank, an active protection system, a circular Doppler radar, an option for a 155 mm gun, and 360-degree ultraviolet high-definition cameras.58 Other defense assessments rate two other tanks—the German Leopard 2A7V and the South Korean K2 Black Panther—as superior to the M-1A2 SEP v3.59

The point is not to pick the best tank in the world. Rather, the point is that although the M-1A2 SEP v3 (the most recent version) is a very good tank, the decisive advantage the U.S. once enjoyed in tank design has disappeared.

Similarly, the U.S. Army’s Patriot Missile System is an excellent system, but countries such as Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and India have either purchased or recently expressed interest in buying the Russian competitor system, the S-400.60 Why? Part of the answer lies in cost. The Patriot system is tremendously expensive; a Patriot battery (one-fourth of a battalion) costs about $3 billion for the launchers and a basic load of missiles, and an S-400 battery has been estimated to cost $500 million.61

Within the Army’s inventory of equipment are thousands of combat systems, including small arms, trucks, aircraft, soldier-carried weapons, radios, tracked vehicles, artillery systems, missiles, and drones. The following sections provide updates with respect to some of the major systems as they pertain to Armored, Stryker, and Infantry BCTs and Combat Aviation Brigades.

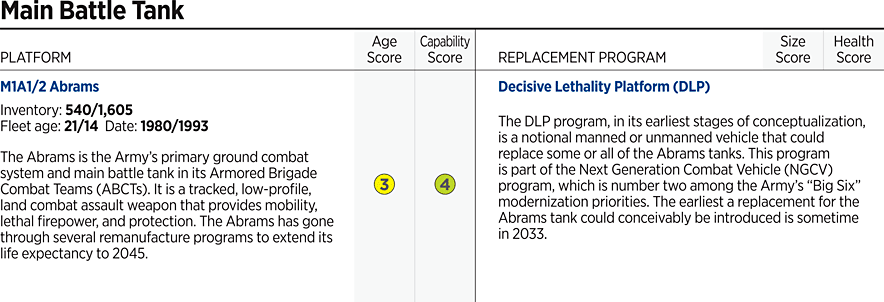

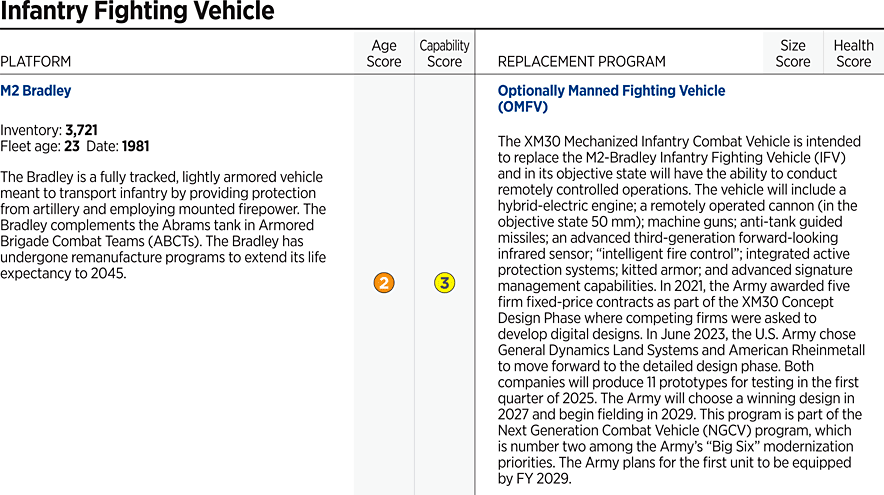

Armored Brigade Combat Team (ABCT). The Armored BCT’s role is to “close with the enemy by means of fire and movement to destroy or capture enemy forces, or to repel enemy attacks by fire, close combat, and counterattack to control land areas, including populations and resources.”62 The Abrams Main Battle Tank (most recent version in production: M1A2 SEPv3, first unit equipped in FY 202063) and Bradley Fighting Vehicle (most recent version: M2A4, first unit equipped in April 202264) are the primary Armored BCT combat platforms.

The M-1 tank and Bradley Fighting Vehicle first entered service in 1980 and 1981, respectively. There are 87 M-1 Abrams tanks and 152 Bradley Fighting Vehicle variants in an ABCT.65 Despite upgrades, the M-1 tank and the Bradley are now at least 40 years old, and their replacements will not arrive until the platforms are at least 50 years old.

Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle (OMFV). The Army’s replacement program for the Bradley, the Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle, was on an aggressive timeline, but the Army cancelled the request for proposals (RFP) in January 2020 and rereleased an RFP for what it called a “concept design” in December 2020. Five teams were selected to come up with designs for the OMFV. The next milestone was in July 2022 when the government released a final RFP. An award for three contractors to produce detailed designs is expected in the second quarter of FY 2023,66 and “[t]he Army then intends to select one vendor for Low-Rate Initial Production near the end of FY2027.”67

Procurement funding for the OMFV does not yet appear in the Army’s FY 2024–FY 2029 program. Flat or declining funding such as the Army is currently experiencing could affect those plans.

A New Tank? A potential clean-sheet replacement for the M-1 tank is even farther down the road. Major General Glenn Dean, Program Officer, Ground Combat Systems, reportedly has said that “funding to pursue what could be next for Abrams would likely not appear in a budget cycle until fiscal 2025 at the earliest.”68 Meanwhile, the Army has another upgrade for the Abrams platform in the works: the M1A2 SEPv4, which would incorporate a “3rd Generation Forward Looking Infrared (3GEN FLIR)” in addition to “new color cameras to the gunner/commander primary sights” as well as “an improved laser range finder, integration of a laser warning receiver system, improved lethality via Fire Control System (FCS) digital communication with a new Advanced Multi-Purpose round, improved accuracy via integration of a meteorological sensor, and improved onboard diagnostics.”69 Fielding will begin in FY 2024.

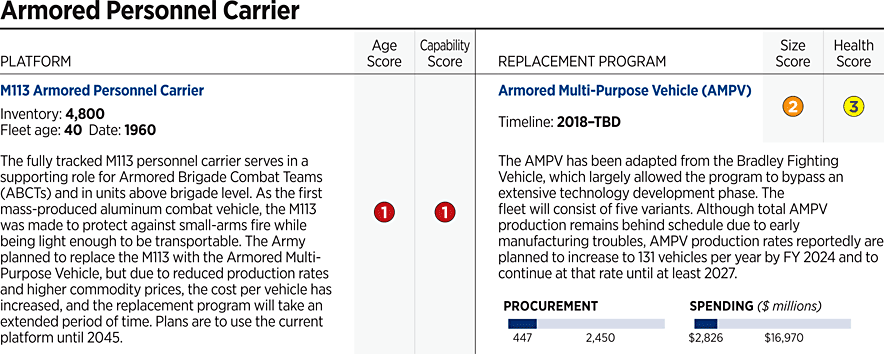

Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle (AMPV). The venerable M113 multi-purpose personnel carrier is also part of an ABCT and fills multiple roles such as mortar carrier and ambulance. It entered service in 1960 and is being replaced by the new Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle (AMPV), which after numerous delays entered low-rate initial production on January 25, 2019. The system’s first fieldings took place on March 13, 2023.70 The Army’s FY 2024 budget includes a request for procurement of 91 AMPVs. At that rate of procurement and given prior year procurements, it will take the Army at least 25 years from 2024 to meet its objective of 2,897 AMPVs by FY 2049.71

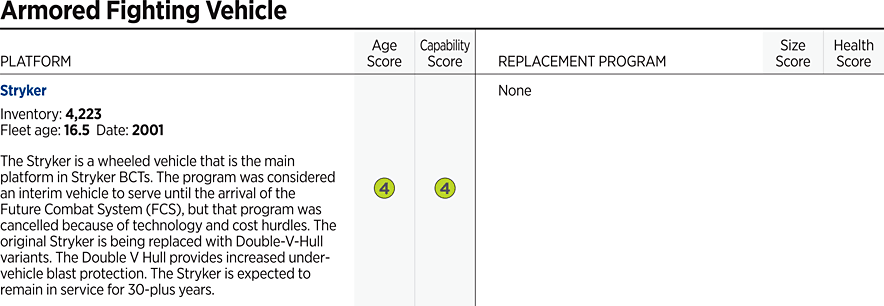

Stryker Brigade Combat Team (SBCT). The Stryker BCT “is an expeditionary combined arms force organized around mounted infantry” and is able to “operate effectively in most terrain and weather conditions” because of its rapid strategic deployment and mobility.72 Stryker BCTs are equipped with approximately 321 eight-wheeled Stryker vehicles.73 Relatively speaking, these vehicles are among the Army’s newest combat platforms, having entered service in 2001.

In response to an Operational Needs Statement, the Stryker BCT in Europe received Strykers fitted with a 30 mm cannon to provide an improved anti-armor capability.74 Based on the success of that effort, the Army decided to outfit at least three of its SBCTs that are equipped with the Double V-hull, which affords better underbody protection against such threats as improvised explosive devices, with the 30 mm autocannon.75 The next SBCT to receive the cannons (after the 2nd Cavalry Regiment) will be the 1-2 SBCT at Joint Base Lewis–McChord in Washington State; delivery was scheduled for July 2023.76 The Army is also integrating Javelin anti-tank missiles on the Stryker platform and began to train crews on this capability in May 2022.77

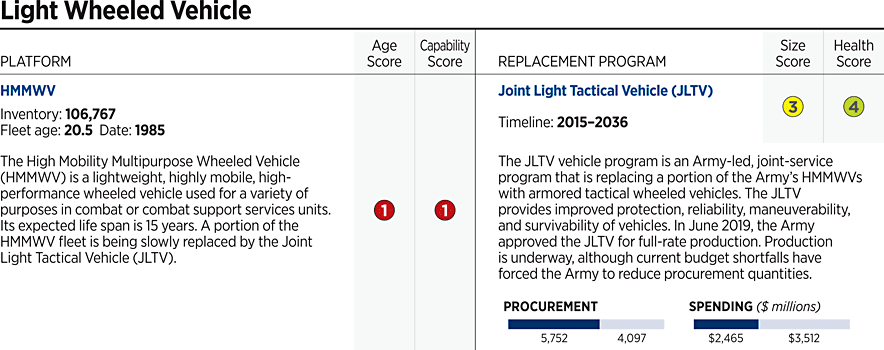

Infantry Brigade Combat Team (IBCT). The Infantry BCT “is an expeditionary, combined arms formation optimized for dismounted operations in complex terrain,” which the Army defines as “a geographical area consisting of an urban center larger than a village and/or of two or more types of restrictive terrain or environmental conditions occupying the same space.”78 Infantry BCTs have fewer vehicles and rely on lighter platforms such as trucks; High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicles (HMMWVs); and Joint Light Tactical Vehicles (JLTVs) for mobility.

Joint Light Tactical Vehicle (JLTV). The JLTV aspires to combine the protection offered by Mine Resistant Ambush Protected Vehicles (MRAPs) with the mobility of the original unarmored HMMWV. The vehicle features design improvements that increase its survivability against anti-armor weapons and improvised explosive devices (IEDs). The Army Procurement Objective is 49,099 trucks,79 replacing about 50 percent of the current HMMWV fleet.

Requested FY 2024 funding of $839.4 million would support procurement of 1,753 JLTVs and 848 trailers. This reflects an increase in funding ($664.1 million was enacted for FY 2023), suggesting that the Army is recommitted to this program. Considering the 4,612 JLTVs the Army has already procured80 and procurement at a rate of 1,753 vehicles (the FY 2024 quantity), the Army will not reach its procurement objective of 49,099 for the JLTV until 2048, leaving it to rely on aging HMMWVs that began fielding in 1983.81

Mobile Protected Firepower (MPF). The Army has developed a light tank, previously called Mobile Protected Firepower and now officially named the M10 Booker, to provide IBCTs with the firepower to engage enemy armored vehicles and fortifications.82 In June 2022, the Army awarded General Dynamics Land Systems a contract for 96 MPF systems. The first units are expected to receive the M10 in the fourth quarter of FY 2025. The Army’s acquisition objective is for 504 M10s, organized in battalions of 42 systems. The $394.6 million requested in the FY 2024 budget will acquire 33 systems.83 At that rate of procurement, the Army will meet its objective in FY 2038.

Ground Mobility Vehicle (GMV). Airborne BCTs are the first IBCTs to receive a new platform to increase their speed and mobility. The GMV (also referred to as the Infantry Squad Vehicle) provides enhanced tactical mobility for an IBCT nine-soldier infantry squad with their associated equipment. GM Defense was selected for the production contract in June 2020. The Army has approved a procurement objective of 11 IBCT sets at 59 vehicles per IBCT for a total of 649 vehicles. The approved Army acquisition objective is 2,593. Given prior procured quantities of 596 and at the procurement rate of 143 per year, the Army will reach its acquisition objective in FY 2037.84

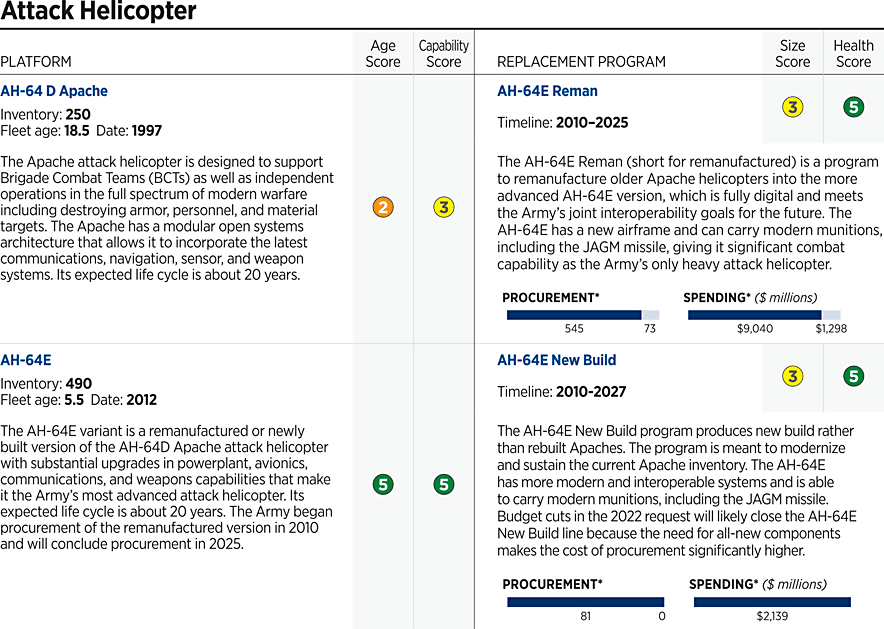

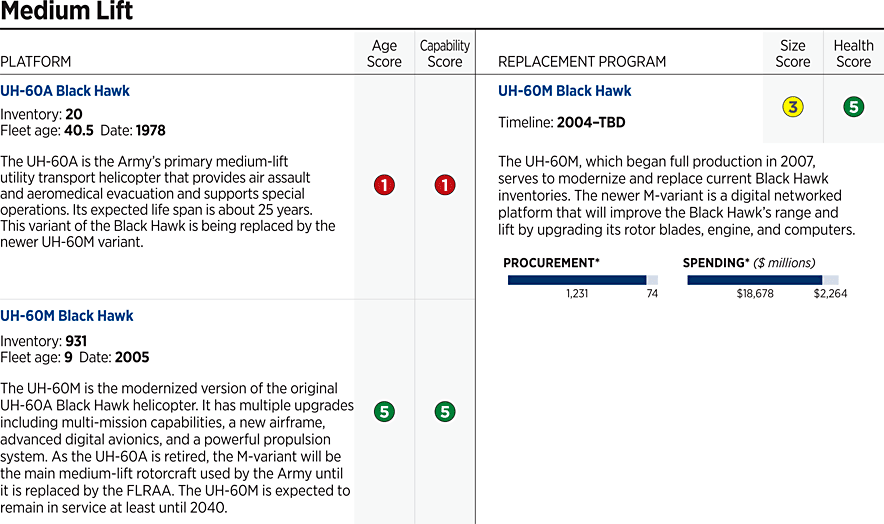

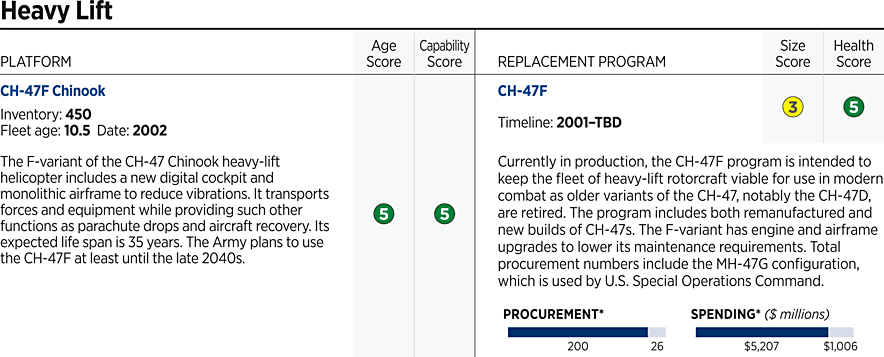

Combat Aviation Brigade. CABs are composed of AH-64 Apache attack, UH-60 Black Hawk medium-lift, and CH-47 Chinook heavy-lift helicopters. The Army has been methodically upgrading these fleets for decades, but the FY 2024 budget request continues the reduction in legacy aircraft procurement that began in FY 2022, presumably to create “budget room” for the planned introduction of two new aircraft: the Future Long-Range Assault Aircraft (FLRAA) and Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft (FARA). This is a continued reflection of downward budget pressure and incurs additional risk for the Army as its legacy helicopters are expected to be around for decades.

UH/HH-60. The acquisition objective for the H-60 medium-lift helicopter is 1,375 H-60Ms and 760 recapitalized 60-A/L/Vs for a total of 2,135 aircraft. The FY 2024 procurement request for the UH-60M is $760.7 million, which would support the procurement of 24 aircraft, 11 less than the 35 that were funded in FY 2023. The FY 2024 budget request reflects planned UH-60 procurement in FY 2026.85

CH-47. The CH-47F Chinook, a rebuilt variant of the Army’s CH-47D heavy-lift helicopter, has an acquisition objective of 535 aircraft and, with no planned replacement on the horizon, is expected to remain the Army’s heavy-lift helicopter for the foreseeable future. The FY 2024 budget request of $221.4 million would support the service life extension of six aircraft, as well as retrofits, all of which would be for the MH-47G special operations model.86

AH-64. The AH-64E heavy attack helicopter has an Army acquisition objective of 812 aircraft (a combination of remanufactured and new build), which is being met by the building of new aircraft and remanufacturing of older AH-64 models. The $828.9 million FY 2024 procurement request would support the purchase of 42 AH-64E aircraft, nine more than the 33 funded in FY 2023 budget.87

Overall, the Army’s equipment inventory, while increasingly dated, is maintained well. Under its current modernization plans, “the Army envisions [the M-1 Abrams Tank, M-2/M-3 Bradley Fighting Vehicle (BFV), and M-1126 Stryker Combat Vehicle] to be in service with Active and National Guard forces beyond FY2028.”88

Future Programs and Efforts. In addition to seeing to the viability of today’s equipment, the military must look to the health of future equipment programs. Although future modernization programs do not represent current hard-power capabilities that can be applied against an enemy force today, they are a leading indicator of a service’s overall fitness for future sustained combat operations. In future years, the service could be forced to engage an enemy with aging equipment and no program in place to maintain viability or endurance in sustained operations.

The U.S. military services are continually assessing how best to stay a step ahead of competitors: whether to modernize the force today with currently available technology or wait to see what investments in research and development produce years down the road. Technologies mature and proliferate, becoming more accessible to a wider array of actors over time.

After 20 years of a singular focus on counterinsurgency followed by concentration on the current readiness of the force, the Army is now playing catch-up in equipment modernization.

New Organizations and Emphasis on Modernization. In 2017, the Army established eight cross-functional teams (CFTs) to improve the management of its top modernization priorities, and in 2018, it established a new four-star headquarters, Army Futures Command, to lead modernization efforts.89 In 2023 the Army announced the creation of a new Cross Functional Team to handle logistics.90

Even though it has been six years, it is still too early to assess whether these new structures, commands, and emphasis will result in long-term improvement in the Army’s modernization posture. The Army aspires to develop and procure an entire new generation of equipment based on its six modernization priorities: “long range precision fires, next generation combat vehicles, future vertical lift, network, air and missile defense, and Soldier lethality.”91

Although the Army has put in place new organizations, plans, and strategies to manage modernization, the future is uncertain, and Army programs remain in a fragile state with only a few in an active procurement status. The Army has shown great willingness to make tough choices and reallocate funding toward its modernization programs, but this has usually been at the expense of end strength or reduction in the total quantity of new items purchased.

As budget challenges such as nuclear deterrence programs, inflation, rising personnel costs, health care, and the need to invest in programs to respond to China’s increasingly aggressive activities continue to present themselves, the Army desperately needs time and funding to modernize its inventory of equipment. Recent modernization programs seem to be on track except for the Extended Range Cannon program,92 the Improved Turbine Engine Program,93 and the Integrated Visual Augmentation System,94 all of which have suffered some setbacks. The Army also is experiencing some success, one example being the number of Stryker vehicle-mounted Maneuver Short Range Air Defense (M-SHORAD) systems that have been delivered to Europe.95 Army officials are currently optimistic about future fielding dates for equipment like the hypersonic weapon firing battery and the Precision Strike Missile, both of which are scheduled to begin delivery in FY 2023, but their success will depend on sustained funding.

Readiness

BCT Readiness. Over the past four years, the Army has made steady progress in increasing the readiness of its forces. Its goal is to have 66 percent of the Regular Army and 33 percent of National Guard BCTs “at the highest levels of readiness.”96

As of July 14, 2023, the Army reported that “83 percent of Active Component Brigade Combat Teams are at the highest levels of tactical readiness.”97 This is 17 percentage points above its goal and two percentage points above last year’s reported level. This means that 25 of the Army’s 31 active BCTs were at either C1 or C2, the two highest levels of tactical readiness, and ready to perform all or most of their wartime missions immediately. The 2023 Index reported that 25 Regular Army BCTs were at the highest levels of readiness.

There also are 27 BCTs in the Army National Guard: five Armor, 20 Infantry, and two Stryker. The Army has allocated two Combat Training Center (CTC) rotations for two National Guard BCTs. These two BCTs “are resourced to achieve company-level proficiency, while the remaining 25 BCTs and enabler units are on a path to platoon minus-level proficiency and will meet Directed Readiness Table requirements.”98 These training levels usually reveal the extent to which additional training time would be required before the unit could be deployed. Given the paucity of data provided by the Army, it is hard to assess the current readiness of ARNG units.

Steady Decline in Training Resources. When measuring resourcing for the training of Brigade Combat Teams, the Army formerly used full-spectrum training miles (FSTMs), representing the number of miles that formations are resourced to drive their primary vehicles on an annual basis. In FY 2024, the Army changed the terminology to Composite Training Miles but explained that they are the same thing. Since FY 2019, these training resources have been declining. In FY 2021, the Army budgeted 1,598 FSTMs to train BCTs to 100 percent of the requirement.99 According to the Army’s FY 2024 budget justification exhibits, only 1,137 Composite Training Miles are funded for non-deployed units. This is a cut of 28 percent, suggesting that unless the Army’s training strategy radically changed, BCTs are funded only to 72 percent of the training requirement.

For Combat Aviation Brigades, the Army uses hours per crew per month (H/C/M), which reflects the number of hours that aviation crews can fly their helicopters per month. The 9.2 flying hours budgeted in the FY 2024 request are 13 percent lower than the 10.6 active flying hours per crew per month enacted in the FY 2023 budget.100

Uncertain Training Level Goals. Starting with the FY 2022 budget justification books, the Army began to omit the Unit Proficiency Level Goal, which for years has been to train a BCT to operate as a BCT; it is likely now training to act as a battalion or company. This implies that brigade combat teams will not be effective in executing brigade-level or brigade-size tasks if called into action. Having competent companies or battalions is one thing; being able to orchestrate their actions to achieve higher-order tactical and operational tasks is much different.

CTC Rotations. The Army uses Combat Training Centers to train its forces to desired levels of proficiency. Specifically, this important program “provide[s] realistic joint and combined arms training…approximating actual combat” and increases “unit readiness for deployment and warfighting.”101 For FY 2024, the Army is resourcing 22 CTC rotations: eight at the National Training Center, eight at the Joint Readiness Training Center, four at the Joint Multinational Readiness Center, and two exportable rotations. Two of these 22 rotations are for Army National Guard Brigades.102

New Readiness Model. The Army has transitioned from one readiness model to another. Its Sustainable Readiness Model, implementation of which began in 2017, was intended to give units more predictability. Its new Regionally Aligned Readiness and Modernization Model (ReARMM) is designed to “better balance operational tempo (OPTEMPO) with dedicated periods for conducting missions, training, and modernization.”103 ReARMM features units that spend eight months in a modernization-training-mission cycle while preparing to deploy to a specific part of the world. The Army shifted to this new model on October 1, 2021.104 Since announcing the model in 2021, the Army has been silent on the topic.

In general, the Army continues to be challenged by structural readiness problems as evidenced by too small a force attempting to satisfy too many global presence requirements and Operations Plan (OPLAN) warfighting requirements. If demand is not reduced, the funding cuts and end strength reduction featured in the FY 2023 budget submission and continued in the FY 2024 submission can be expected to result in a continued decline in readiness.

Scoring the U.S. Army

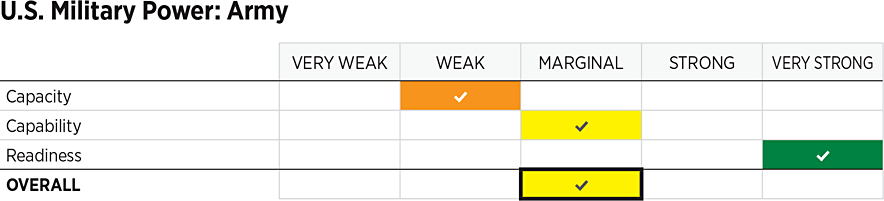

Capacity Score: Weak

Historical evidence shows that, on average, the Army needs 21 Brigade Combat Teams to fight one major regional conflict (MRC). Based on a conversion of roughly 3.5 BCTs per division, the Army deployed 21 BCTs in Korea, 25 in Vietnam, 14 in the Persian Gulf War, and approximately four in Operation Iraqi Freedom—an average of 16 BCTs (or 21 if the much smaller Operation Iraqi Freedom initial invasion operation is excluded).

In the 2010 Quadrennial Defense Review, the Obama Administration recommended a force capable of deploying 45 Active BCTs. Previous government force-sizing documents discuss Army force structure in terms of divisions and consistently advocate for 10–11 divisions, which equates to roughly 37 Active BCTs.

Considering the varying recommendations of 35–45 BCTs and the actual experience of nearly 21 BCTs deployed per major engagement, our assessment is that 42 BCTs would be needed to fight two MRCs.105 Taking into account the need for a strategic reserve, the Army force should also include an additional 20 percent of the 42 BCTs, resulting in an overall requirement of 50 BCTs.

Previous editions of the Index of U.S. Military Strength counted a small number of Army National Guard BCTs in the overall count of available BCTs. Because the Army no longer makes mention of Army National Guard BCTs at the highest state of readiness, they are no longer counted in this edition of the Index. The Army has 31 Regular Army BCTs compared to a two-MRC construct requirement of 50. The Army’s overall capacity score therefore remains unchanged from 2022.

- Two-MRC Benchmark: 50 Brigade Combat Teams.

- Actual FY 2022 Level: 31 Regular Army Brigade Combat Teams.

The Army’s current BCT capacity equals 62 percent of the two-MRC benchmark and is therefore scored as “weak.”

Capability Score: Marginal

The Army’s aggregate capability score remains “marginal.” This aggregate score is a result of “marginal” scores for “Age of Equipment,” “Size of Modernization Programs,” and “Health of Modernization Programs.” More detail on these programs can be found in the equipment appendix following this section. The Army is scored “weak” for “Capability of Equipment.”

Despite modest progress with the JLTV, M10 Booker, Ground Mobility Vehicle, and AMPV programs, and in spite of such promising developments as creation of Army Futures Command, CFTs, and the initiation of new Research, Development, Testing and Evaluation (RDTE) funded programs, nearly all new Army equipment programs remain in the development phase and in most cases are at least a year from being fielded. FY 2024 requested funding levels for procurement and research and development are down 8 percent compared to the FY 2023 enacted levels, which further slows the pace of Army equipping and reduces the speed of procurement to below industry’s minimum sustainment rates in some cases. The result of the FY 2024 budget request would be an Army that is aging faster than it is modernizing.

Readiness Score: Very Strong

The Army reports that 83 percent of its 31 Regular Army BCTs are at the highest state of readiness.106 The Army’s internal requirement is for “66 percent…of the active component BCTs [to be] at the highest readiness levels.”107 Using the assessment methods of this Index, this results in a percentage of service requirement of 100 percent, or “very strong.”

Overall U.S. Army Score: Marginal

The Army’s overall score is calculated based on an unweighted average of its capacity, capability, and readiness scores. The unweighted average is 3.33; thus, the overall Army score is “marginal.” This was derived from the aggregate score for capacity (“weak”); capability (“marginal”); and readiness (“very strong”). This score is the same as the assessment of the 2023 Index, which rated the Army as “marginal” overall.

Endnotes

[1] Jim Garamone, “Vice Chiefs Talk Recruiting Shortfalls, Readiness Issues,” U.S. Department of Defense, April 20, 2023, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3369472/vice-chiefs-talk-recruiting-shortfalls-readiness-issues/#:~:text=%22Right%20now%2C%20we%20have%20137%2C000%20soldiers%20in%20over,has%20the%20stocks%20to%20fight%20when%20called%20upon (accessed August 21, 2023).

[2] The Honorable Christine E. Wormuth, Secretary of the Army, and General James C. McConville, Chief of Staff, United States Army, statement “On the Posture of the United States Army” before the Subcommittee on Defense, Committee on Appropriations, U.S. Senate, May 2, 2023, p. 3, https://www.appropriations.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/HON%20Wormuth%20and%20GEN%20McConville%20-%20SAC-D%20Army%20Posture1.pdf (accessed August 21, 2023).

[3] Ibid., p. 4.

[4] Christine E. Wormuth, “Message from the Secretary of the Army to the Force,” U.S. Army, February 8, 2022, https://www.army.mil/article/253814/message_from_the_secretary_of_the_army_to_the_force (accessed August 21, 2023).

[5] The Army’s FY 2019 total obligational authority (TOA) was $181.1 billion. See Table 6-3, “Department of Defense TOA by Military Department,” in U.S. Department of Defense, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), National Defense Budget Estimates for FY 2024, May 2023, p. 102, https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/FY2024/FY24_Green_Book.pdf (accessed August 23, 2023), and Table 6-16, “Army TOA by Public Law Title,” in ibid., p. 196.

[6] U.S. Army, Assistant Secretary of the Army (Financial Management and Comptroller), FY 2024 President’s Budget Highlights, March 2023, p. 27, https://www.asafm.army.mil/Portals/72/Documents/BudgetMaterial/2024/pbr/Army%20FY%202024%20Budget%20Highlights.pdf (accessed August 21, 2023).

[7] Blake Herzinger, “Give the U.S. Navy the Army’s Money,” Foreign Policy, April 28, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/04/28/navy-army-defense-budget-china/ (accessed August 21, 2023).

[8] Brad Knickerbocker, “Gates’s Warning: Avoid Land War in Asia, Middle East, and Africa,” The Christian Science Monitor, February 26, 2011, https://www.csmonitor.com/USA/Military/2011/0226/Gates-s-warning-Avoid-land-war-in-Asia-Middle-East-and-Africa (accessed August 21, 2023).

[9] Thomas Spoehr, “The Incredible Shrinking Army: NDAA End Strength Levels Are a Mistake,” Breaking Defense, December 20, 2022, https://breakingdefense.com/2022/12/the-incredible-shrinking-army-ndaa-end-strength-levels-are-a-mistake/ (accessed August 22, 2023).

[10] Garamone, “Vice Chiefs Talk Recruiting Shortfalls, Readiness Issues.”

[11] Thomas Spoehr, “Military Recruiting Faces Its Biggest Challenge in Years,” Heritage Foundation Commentary, May 13, 2022, https://www.heritage.org/defense/commentary/military-recruiting-faces-its-biggest-challenge-years.

[12] Courtney Kube and Mosheh Gains, “The Army Has So Far Recruited Only About Half the Soldiers It Hoped for Fiscal 2022, Army Secretary Says,” NBC News, August 11, 2022, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/military/army-far-recruited-half-soldiers-hoped-fiscal-2022-rcna42740 (accessed August 22, 2023).

[13] News release, “The Employment Situation—July 2023,” U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, August 4, 2023, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf (accessed August 23, 2023).

[14] “Report of the National Independent Panel on Military Service and Readiness,” Heritage Foundation Special Report, March 30, 2023, pp. 6–10, https://www.heritage.org/sites/default/files/2023-03/2023_03_0087_NIPMSR_FullReport_FINAL_DIGITAL.pdf.

[15] U.S. Department of Defense, 2022 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America Including the 2022 Nuclear Posture Review and the 2022 Missile Defense Review, https://media.defense.gov/2022/Oct/27/2003103845/-1/-1/1/2022-NATIONAL-DEFENSE-STRATEGY-NPR-MDR.PDF (accessed August 23, 2023). See also National Security Strategy, The White House, October 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Biden-Harris-Administrations-National-Security-Strategy-10.2022.pdf (accessed August 23, 2023).

[16] John A. Tirpak, “Next National Defense Strategy Should Return to Two-War Force Construct,” Air & Space Forces Magazine, June 15, 2021, https://www.airforcemag.com/next-national-defense-strategy-should-return-to-two-war-force-construct/ (accessed August 23, 2023). The Commission on the National Defense Strategy for the United States similarly noted that “a two-war force sizing construct makes more strategic sense today than at any previous point in the post–Cold War era.” See Commission on the National Defense Strategy for the United States, Providing for the Common Defense: The Assessment and Recommendations of the National Defense Strategy Commission (Washington: United States Institute of Peace, 2018), p. 35, https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/2018-11/providing-for-the-common-defense.pdf (accessed August, 2023). The report is undated but was released in November 2018. Press release, “National Defense Strategy Commission Releases Its Review of 2018 National Defense Strategy,” United States Institute of Peace, November 13, 2018, https://www.usip.org/press/2018/11/national-defense-strategy-commission-releases-its-review-2018-national-defense (accessed August 23, 2023).

[17] Loren B. Thompson, “Army Move to Kill Air Defense System Leaves Other Services and Allies in the Lurch,” Lexington Institute, September 30, 2010, https://www.lexingtoninstitute.org/army-move-to-kill-air-defense-system-leaves-other-services-and-allies-in-the-lurch/ (accessed August 23, 2023).

[18] Mike Stone, “Pentagon Awards Raytheon $1.2 Bln Contract for Ukrainian NASAMS,” Reuters, November 30, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/us/pentagon-award-12-bln-contract-raytheon-ukrainian-nasams-source-document-2022-11-30/ (accessed August 23, 2023).

[19] Rick Maze, “Urgent Push: McConville: ‘We Must Modernize Now,’” Association of the United States Army, January 14, 2021, https://www.ausa.org/articles/urgent-push-mcconville-we-must-modernize-now (accessed August 23, 2023).

[20] S. 365, Budget Control Act of 2011, Public Law 112-25, 112th Cong., August 2, 2011, https://www.congress.gov/112/plaws/publ25/PLAW-112publ25.pdf (accessed August 23, 2023).

[21] David Alexander, “Big Budget Cuts Pose ‘Tough, Tough Choices’ for Pentagon—Hagel,” Reuters, March 6, 2014, https://www.reuters.com/article/usa-defense-budget/big-budget-cuts-pose-tough-tough-choices-for-pentagon-hagel-idINL1N0M31UB20140306 (accessed August 23, 2023). See also testimony of Honorable Chuck Hagel, Secretary of Defense, in hearing, Fiscal Year 2015 National Defense Authorization Budget Request from the Department of Defense, Committee on Armed Services, U.S. House of Representatives, 113th Cong., 2nd Sess., March 6, 2014, pp. 10 and 21–22, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-113hhrg87616/pdf/CHRG-113hhrg87616.pdf (accessed August 23, 2023).

[22] Elizabeth Howe, “Trump-Era Efforts to Boost Military Readiness Produced Mixed Results, GAO Finds,” Defense One, April 16, 2021, https://www.defenseone.com/policy/2021/04/trump-era-efforts-boost-military-readiness-produced-mixed-results-gao-finds/173411/ (accessed August 23, 2023), and U.S. Government Accountability Office, Military Readiness: Department of Defense Domain Readiness Varied from Fiscal Year 2017 Through Fiscal Year 2019, GAO-21-279, April 2021, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-21-279.pdf (accessed August 23, 2023).

[23] National Security Strategy, The White House, October 2022.

[24] Commission on the National Defense Strategy for the United States, Providing for the Common Defense: The Assessment and Recommendations of the National Defense Strategy Commission, p xii. “Real” growth means that the growth is in addition to inflation. As an example, if inflation equals 2 percent each year, real growth of 3 percent will equal 5 percent net growth.

[25] Gabe Camarillo, Under Secretary of the Army, “Army Fiscal Year 2024 Budget Overview,” PowerPoint Presentation, p. 14, https://www.asafm.army.mil/Portals/72/Documents/BudgetMaterial/2024/pbr/Army%20FY%202024%20Budget%20Overview%20Briefing.pdf (accessed August 21, 2023); Table 6-3, “Department of Defense TOA by Military Department,” in U.S. Department of Defense, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), National Defense Budget Estimates for FY 2024, p. 102; and Table 6.16, “Army TOA by Public Law Title,” in ibid., p. 196.

[26] Matthew Beinart, “Army Secretary Tells Lawmakers She Would ‘Certainly Welcome Additional Funds’ to Service’s Budget,” Defense Daily, June 15, 2021, https://www.defensedaily.com/army-secretary-tells-lawmakers-certainly-welcome-additional-funds-services-budget/army/ (accessed August 24, 2023).

[27] See “Army’s FY-24 Unfunded Priorities List,” Inside Defense, March 27, 2023, https://insidedefense.com/document/armys-fy-24-unfunded-priorities-list (accessed August 23, 2023). Subscription required.

[28] Headquarters, U.S. Department of the Army, Field Manual 3-96, Brigade Combat Team, January 19, 2021, p. xi, https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN31505-FM_3-96-000-WEB-1.pdf (accessed August 23, 2023).

[29] Congressional Budget Office, The U.S. Military’s Force Structure: A Primer, 2021 Update, May 2021, pp. 17–35, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2021-05/57088-Force-Structure-Primer.pdf (accessed August 23, 2023).

[30] AUSA Staff, “Army Brigade Combat Teams Are Reduced from 45 to 33,” Association of the United States Army, August 1, 2013, https://www.ausa.org/articles/army-brigade-combat-teams-are-reduced-45-33 (accessed August 23, 2023).

[31] Exhibit OP-5, Subactivity Group 111, “Budget Activity 01: Operating Forces, Activity Group 11: Land Forces, Detail by Subactivity Group 111: Maneuver Units,” in U.S. Department of the Army, Department of the Army Fiscal Year (FY) 2024 Budget Estimates, Army, Volume I, Operations and Maintenance, Army, Justification of Estimates, March 2023, p. 62, https://www.asafm.army.mil/Portals/72/Documents/BudgetMaterial/2024/Base%20Budget/Operation%20and%20Maintenance/Regular%20Army%20Operation%20and%20Maintenance%20Volume%201.pdf (accessed August 21, 2023).

[32] John H. Pendleton, Director, Defense Capabilities and Management, U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Army Readiness: Progress and Challenges in Rebuilding Personnel, Equipping and Training,” testimony before the Subcommittee on Readiness and Management Support, Committee on Armed Services, U.S. Senate, GAO-19-367T, February 6, 2019, p. 7, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-19-367t.pdf (accessed August 23, 2023).

[33] Exhibit OP-5, Subactivity Group 116, “Budget Activity 01: Operating Forces, Activity Group 11: Land Forces, Detail by Subactivity Group 116: Aviation Assets,” in U.S. Department of the Army, Department of the Army Fiscal Year (FY) 2024 Budget Estimates, Army, Volume I, Operations and Maintenance, Army: Justification of Estimates, p. 128.

[34] Data extrapolated to match the new Army Active end strength of 452,000 assuming personnel categories shrink proportionately from data found in Table 2.2, “Average Distribution of the Department of the Army’s Military Personnel, 2021 to 2025,” in Congressional Budget Office, The U.S. Military’s Force Structure: A Primer, 2021 Update, p. 20.

[35] Steve Beynon and Rebecca Kheel, “Army Special Operations Could Be Cut 10% as Military Looks to Conventional Warfare,” Military.com, May 24, 2023, https://www.military.com/daily-news/2023/05/24/army-weighing-10-cut-special-forces-coming-years.html (accessed August 23, 2023).

[36] U.S. Army, Training and Doctrine Command, The U.S. Army in Multi-Domain Operations 2028, TRADOC Pamphlet No. 525-3-1, December 6, 2018, https://api.army.mil/e2/c/downloads/2021/02/26/b45372c1/20181206-tp525-3-1-the-us-army-in-mdo-2028-final.pdf (accessed August 23, 2023).

[37] Eric Pilgrim, “Historic V Corps Activates at Fort Knox on ‘Picture Perfect’ Day,” U.S. Army, October 16, 2020, https://www.army.mil/article/240038/historic_v_corps_activates_at_fort_knox_on_picture_perfect_day (accessed August 23, 2023).

[38] Joe Lacdan, “Army Re-Activates Historic Airborne Unit, Reaffirms Commitment to Arctic Strategy,” U.S. Army, June 8, 2022, https://www.army.mil/article/257356/army_re_activates_historic_airborne_unit_reaffirms_commitment_to_arctic_strategy (accessed August 23, 2023).

[39] Andrew Feickert, “The Army’s Multi-Domain Task Force (MDTF),” Congressional Research Service In Focus No. IF11797, updated March 16, 2023, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11797 (accessed August 24, 2023).

[40] Ibid.

[41] Russell K. Shimooka, “Third Multi-Domain Task Force Activated for Indo-Pacific Duty,” U.S. Army, September 23, 2022, https://www.army.mil/article/260505/third_multi_domain_task_force_activated_for_indo_pacific_duty (accessed August 23, 2023).

[42] Andrew Feickert, “Army Security Force Assistance Brigades (SFABs),” Congressional Research Service In Focus No. 10675, updated August 21, 2023, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF10675 (accessed August 21, 2023).

[43] H.R. 7776, National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023, Public Law 117-263, 117th Cong., December 23, 2022, Sections 401 and 411, https://www.congress.gov/117/plaws/publ263/PLAW-117publ263.pdf (accessed August 23, 2023).

[44] Jaspreet Gill, “McConville: Army Active-Duty End Strength Should Be ‘Somewhere Around’ 540K,” Inside Defense, March 25, 2021, https://insidedefense.com/insider/mcconville-army-active-duty-end-strength-should-be-somewhere-around-540k (accessed August 24, 2023). Punctuation as in original. See also Jen Judson, “US Army Chief Says End Strength Will Stay Flat in Upcoming Budgets,” Defense News, March 16, 2021, https://www.defensenews.com/digital-show-dailies/global-force-symposium/2021/03/17/army-chief-says-end-strength-numbers-to-stay-flat-in-upcoming-budgets/ (accessed August 24, 2023).

[45] Meghann Myers, “Big Bonus Changes, Filling Units, New Slogan: Inside the Army’s Push to Recruit and Man a Bigger Force,” Army Times, March 28, 2019, https://www.armytimes.com/news/your-army/2019/03/28/big-bonus-changes-filling-units-marketing-inside-the-armys-push-to-recruit-and-man-a-bigger-force/ (accessed August 23, 2023).

[46] Thomas Spoehr, “The Incredible Shrinking Army: NDAA End Strength Levels Are a Mistake,” Breaking Defense, December 20, 2022, https://breakingdefense.com/2022/12/the-incredible-shrinking-army-ndaa-end-strength-levels-are-a-mistake/ (accessed August 22, 2023).

[47] Commission on the National Defense Strategy for the United States, Providing for the Common Defense: The Assessment and Recommendations of the National Defense Strategy Commission, pp. 35–36. Emphasis in original.

[48] Haley Britzky, “The Army Knows Its Op-tempo Is ‘Unsustainable’ but Can’t Seem to Fix It,” Task & Purpose, March 29, 2022, https://taskandpurpose.com/news/army-training-rotations-optempo-budget/ (accessed August 23, 2023).

[49] Tim Kane, “Global U.S. Troop Deployment, 1950–2003,” Heritage Foundation Report, October 27, 2004, https://www.heritage.org/defense/report/global-us-troop-deployment-1950-2003.

[50] Meghann Myers, “Pentagon’s Top General Suggests More Permanent Basing in Europe, but with Rotational Manning,” Military Times, April 5, 2022, https://www.militarytimes.com/news/pentagon-congress/2022/04/05/pentagons-top-general-suggests-more-permanent-basing-in-europe-but-with-rotational-manning/ (accessed August 23, 2023).

[51] See Andrew Gregory, “Maintaining a Deep Bench: Why Armored BCT Rotations in Europe and Korea Are Best for America’s Global Security Requirements,” Modern War Institute at West Point, July 31, 2017, https://mwi.usma.edu/maintaining-deep-bench-armored-bct-rotations-europe-korea-best-americas-global-security-requirements/ (accessed August 23, 2023), and Daniel Kochis and Thomas Spoehr, “It’s Time to Move US Forces Back to Europe,” Heritage Foundation Commentary, September 15, 2017, https://www.heritage.org/defense/commentary/its-time-move-us-forces-back-europe.

[52] Association of the United States Army, “Army Modernization Stays ‘On Track,” May 11, 2023, https://www.ausa.org/news/army-modernization-stays-track (accessed August 23, 2023).

[53] OCSA Staff, “2020 Eisenhower Presentation ‘The Time Is Now,’” U.S. Army, October 20, 2020, https://www.army.mil/article/240127/2020_eisenhower_presentation_the_time_is_now#:~:text=I%20would%20suggest%2C%20that%20about%20every%2040%20years%2C,Great%20Power%20Competition%20environment%20that%20we%20live%20in (accessed August 24, 2023).

[54] Time to reach Army Acquisition Objectives is calculated by comparing already procured quantities found on Army P-40 forms in the FY 2024 procurement budget exhibits with the procurement quantities for FY 2024 and the Army Acquisition Objectives to understand how long it will take to reach the goals.

[55] Center for Strategic and International Studies, Missile Defense Project, “Missiles of China,” Missile Threat, last updated April 12, 2021, https://missilethreat.csis.org/country/china/ (accessed August 23, 2023).

[56] Center for Strategic and International Studies, Missile Defense Project, “Missiles of Russia,” Missile Threat, last updated August 10, 2021, https://missilethreat.csis.org/country/russia/ (accessed August 23, 2023).

[57] Andrew Eversden, “The Army Could Get Its Next-Gen Precision Strike Missiles in FY27,” Breaking Defense, May 3, 2022, https://breakingdefense.com/2022/05/the-army-could-get-its-next-gen-precision-strike-missiles-in-fy27/ (accessed August 23, 2023).

[58] Editorial Staff, “Russia’s T-14 Armata Next Gen. Tank Finally Deployed to Ukrainian Frontlines: What Will Its Value Be?” Military Watch Magazine, Force Index, April 25, 2023, https://militarywatchmagazine.com/article/t14-deployed-ukraine-belated (accessed August 23, 2023).

[59] Brent M. Eastwood, “Armored Legends: The 3 Best Tanks on Earth, Ranked,” 1945, July 28, 2023, https://www.19fortyfive.com/2021/11/armored-legends-the-3-best-tanks-on-earth-ranked/ (accessed August 23, 2023).

[60] Amanda Macias, “At Least 13 Countries Are Interested in Buying a Russian Missile System Instead of Platforms Made by US Companies, Despite the Threat of Sanctions,” CNBC, updated November 15, 2018, https://www.cnbc.com/2018/11/14/countries-interested-in-buying-russian-missile-system-despite-us-sanction-threats.html (accessed August 22, 2023).

[61] Amanda Macias, “Russia Is Luring International Arms Buyers with a Missile System That Costs Much Less Than Models Made by American Companies,” CNBC, November 19, 2018, https://www.cnbc.com/2018/11/19/russia-lures-buyers-as-s-400-missile-system-costs-less-than-us-models.html (accessed August 22, 2023).

[62] Headquarters, U.S. Department of the Army, Field Manual 3-96, Brigade Combat Team, p. 1-15.

[63] U.S. Army, Acquisition Support Center, “Abrams Main Battle Tank,” updated 2022, https://asc.army.mil/web/portfolio-item/gcs-m1-abrams-main-battle-tank/ (accessed August 23, 2023).

[64] Capt. Sean Minton, “US Army Equips First Unit with Modernized Bradley,” U.S. Army, April 23, 2022, https://www.army.mil/article/255980/us_army_equips_first_unit_with_modernized_bradley (accessed August 23, 2023).

[65] Table 5, “ABCT Allocations,” in Andrew Feickert, “The Army’s M-1 Abrams, M-2/M-3 Bradley, and M-1126 Stryker: Background and Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service Report for Members and Committees of Congress No. R44229, updated April 5, 2016, p. 13, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R44229/6 (accessed August 21, 2023).

[66] Jen Judson, “US Army Readies Request for Prototype Designs of Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle,” Defense News, April 1, 2022, https://www.defensenews.com/land/2022/04/01/us-army-readies-request-for-prototype-designs-of-optionally-manned-fighting-vehicle/ (accessed August 22, 2023).

[67] Andrew Feickert, “The Army’s XM-30 Mechanized Infantry Combat Vehicle (Formerly Known as the Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle [OMFV]),” Congressional Research Service In Focus No. 12094, updated June 27, 2023, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF12094 (accessed August 21, 2023).

[68] Jen Judson, “What Comes After Abrams Tanks? The Army Is Working on Possibilities,” Defense News, October 14, 2022, https://www.defensenews.com/digital-show-dailies/ausa/2022/10/14/what-comes-after-abrams-tanks-the-army-is-working-on-possibilities/ (accessed August 22, 2023).

[69] Exhibit P-40, “Budget Line Item Justification: PB 2024 Army, Appropriation / Budget Activity / Budget Sub Activity: 2033A: Procurement of W&TCV, Army / BA 01: Tracked Combat Vehicles / BSA 20: Tracked Combat Vehicles, P-1 Line Item Number / Title: 6500GA0750 / Abrams Upgrade Program,” in U.S. Department of the Army, Department of Defense Fiscal Year (FY) 2024 Budget Estimates, Army, Justification Book Volume 1 of 1, Procurement of W&TCV, Army, March 2023, p. 114, https://www.asafm.army.mil/Portals/72/Documents/BudgetMaterial/2024/Base%20Budget/Procurement/Procurement%20of%20Weapons%20and%20Tracked%20Combat%20Vehicles.pdf (accessed August 21, 2023).

[70] Andrew Feickert, “The Army’s Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle (AMPV),” Congressional Research Service In Focus No. IF11741, updated March 15, 2023, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/weapons/IF11741.pdf (accessed August 21, 2023).

[71] Exhibit P-40, “Budget Line Item Justification: PB 2024 Army, Appropriation / Budget Activity / Budget Sub Activity: 2033A: Procurement of W&TCV, Army / BA 01: Tracked Combat Vehicles / BSA 10: Tracked Combat Vehicles, P-1 Line Item Number / Title: 2944G80819 / Armored Multi Purpose Vehicle (AMPV),” in U.S. Department of the Army, Department of Defense Fiscal Year (FY) 2024 Budget Estimates, Army, Justification Book Volume 1 of 1, Procurement of W&TCV, Army, March 2023, p. 3, https://www.asafm.army.mil/Portals/72/Documents/BudgetMaterial/2024/Base%20Budget/Procurement/Procurement%20of%20Weapons%20and%20Tracked%20Combat%20Vehicles.pdf (accessed August 23, 2023).

[72] Headquarters, Department of the Army, Field Manual 3-96, Brigade Combat Team, p. 1-1.

[73] Table 6, “SBCT Allocations,” in Feickert, “The Army’s M-1 Abrams, M-2/M-3 Bradley, and M-1126 Stryker: Background and Issues for Congress,” p. 13.

[74] Kyle Rempfer, “New Upgunned Stryker Arrives in Europe,” Army Times, December 19, 2017, https://www.armytimes.com/news/2017/12/19/new-upgunned-stryker-arrives-in-europe/ (accessed August 22, 2023).

[75] Sydney J. Freedberg Jr., “Army Reassures Anxious Industry over Stryker Cannon Competition,” Breaking Defense, June 17, 2020, https://breakingdefense.com/2020/06/army-rebuffs-anxiety-over-stryker-cannon-competition/ (accessed August 23, 2023).

[76] Inder Singh Bisht, “Oshkosh Delivers First Stryker with 30 mm Weapon System to US Army,” The Defense Post, August 3, 2022, https://www.thedefensepost.com/2022/08/03/oshkosh-stryker-30mm-weapon-system/ (accessed August 23, 2023).

[77] Sgt. Gabrielle Pena, “Stryker Brigade Combat Team Equips Modernized Missile System,” U.S. Army, May 3, 2022, https://www.army.mil/article/256358/stryker_brigade_combat_team_equips_modernized_missile_system (accessed August 23, 2023).

[78] Headquarters, Department of the Army, Field Manual 3-96, Brigade Combat Team, p. 1-1. Emphasis in original.

[79] Exhibit P-40, “Budget Line Item Justification: PB 2024 Army, Appropriation / Budget Activity / Budget Sub Activity: 2035A: Other Procurement, Army / BA 01: Tactical and Support Vehicles / BSA 10: Tactical Vehicles, P-40 Line Item Number / Title: 5731D15610 / Joint Light Tactical Vehicle Family of Vehicles,” in U.S. Department of the Army, Department of Defense Fiscal Year (FY) 2024 Budget Estimates, Army, Justification Book Volume 1 of 3, Other Procurement, Army, Tactical and Support Vehicles, Budget Activity 1, March 2023, p. 49, https://www.asafm.army.mil/Portals/72/Documents/BudgetMaterial/2024/Base%20Budget/Procurement/Other%20Procurement%20-%20BA%201%20-%20Tactical%20&%20Support%20Vehicles.pdf (accessed August 28, 2023).

[80] Ibid., pp. 51 and 52.

[81] Procurement objective of 49,099 trucks minus already procured JLTV trucks (6,365) = 42,734, and 42,734/1,753 = 24.4 years.

[82] Jen Judson, “US Army’s New Combat Vehicle Named for Soldiers Killed in Iraq, WWII,” Defense News, June 10, 2023, https://www.defensenews.com/land/2023/06/10/us-armys-new-combat-vehicle-named-for-soldiers-killed-in-iraq-wwii/ (accessed August 22, 2023).

[83] Andrew Feickert, “The Army’s Mobile Protected Firepower (MPF) System,” Congressional Research Service In Focus No. 11859, updated April 6, 2023, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11859 (accessed August 22, 2023).

[84] Exhibit P-40, “Budget Line Item Justification: PB 23 Army, Appropriation / Budget Activity / Budget Sub Activity: 2035A: Other Procurement, Army / BA 01: Tactical and Support Vehicles / BSA 10: Tactical Vehicles, P-1 Line Item Number / Title: 3484D15501 / Ground Mobility Vehicles (GMV),” in U.S. Department of the Army, Department of Defense Fiscal Year (FY) 2024 Budget Estimates, Army, Justification Book Volume 1 of 3, Other Procurement, Army, Tactical and Support Vehicles, Budget Activity 1, March 2023, p. 39, https://www.asafm.army.mil/Portals/72/Documents/BudgetMaterial/2024/Base%20Budget/Procurement/Other%20Procurement%20-%20BA%201%20-%20Tactical%20&%20Support%20Vehicles.pdf (accessed August 23, 2023).

[85] Exhibit P-40, “Budget Line Item Justification: PB 2024 Army, Appropriation / Budget Activity / Budget Sub Activity: 2031A: Aircraft Procurement, Army / BA 01: Aircraft / BSA 20: Rotary, P-1 Line Item Number / Title: 6771AA0005 / UH-60 Blackhawk M Model (MYP),” in U.S. Department of the Army, Department of Defense Fiscal Year (FY) 2024 Budget Estimates, Army, Justification Book Volume 1 of 1, Aircraft Procurement, Army, March 2023, p. 37, https://www.asafm.army.mil/Portals/72/Documents/BudgetMaterial/2024/Base%20Budget/Procurement/Aircraft%20Procurement%20Army.pdf (accessed August 23, 2023).

[86] Exhibit P-40, “Budget Line Item Justification: PB 2024 Army, Appropriation / Budget Activity / Budget Sub Activity: 2031A: Aircraft Procurement, Army / BA 01: Aircraft / BSA 20: Rotary, P-1 Line Item Number / Title: 6775A05101 / CH-47 Helicopter,” in ibid., pp. 60–61.

[87] Exhibit P-40, “Budget Line Item Justification: PB 2024 Army, Appropriation / Budget Activity / Budget Sub Activity: 2031A: Aircraft Procurement, Army / BA 01: Aircraft / BSA 20: Rotary, P-1 Line Item Number / Title: 5757A05111 / AH-64 Apache Block IIIA Reman,” in ibid., pp. 19–20.

[88] Feickert, “The Army’s M-1 Abrams, M-2/M-3 Bradley, and M-1126 Stryker: Background and Issues for Congress,” p. 1.

[89] U.S. Army, “2019 Army Modernization Strategy: Investing in the Future,” pp. 1, 6, and 7, https://www.army.mil/e2/downloads/rv7/2019_army_modernization_strategy_final.pdf (accessed August 23, 2023).

[90] Jen Judson, “US Army Forms New Modernization Team to Tackle Contested Logistics,” Defense News, March 29, 2023, https://www.defensenews.com/land/2023/03/29/us-army-forms-new-modernization-team-to-tackle-contested-logistics/ (accessed August 22, 2023).

[91] U.S. Army, “2019 Army Modernization Strategy: Investing in the Future,” p. 3. See also ibid., pp. 6 and 7.

[92] Ashley Roque, “Army Moving ERCA, LTAMDS from Rapid Prototyping to Major Capability Acquisition,” Breaking Defense, June 8, 2023, https://breakingdefense.com/2023/06/army-moving-erca-ltamds-from-rapid-prototyping-to-major-capability-acquisition/ (accessed August 23, 2023).