Much has been said in recent years about a “race” or “scramble” to secure resources in the Arctic Ocean as polar ice recedes, inevitably leading to conflict in the region. But reality paints a very different picture. Over the past decades, Arctic nations have worked together to advance their shared goals for the region, and relations among the United States and other Arctic nations on Arctic issues are characterized by collaboration, not conflict.

In many ways, the Arctic serves as a model for regional cooperation and multilateral coordination. Even before the end of the Cold War, the eight Arctic states—Canada, Denmark (via Greenland), Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, the USSR, and the United States—met during 1989–1991 to develop a plan for protecting the Arctic environment. The Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy that resulted from these meetings was a groundbreaking step in multilateral cooperation among the Arctic states and formed the basis for the founding of the Arctic Council in 1996.

Yet proponents of U.S. accession to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) insist that the United States is greatly hindered or even incapable of advancing its Arctic interests because it has not ratified the convention. The facts and evidence prove otherwise.

This paper demonstrates how the U.S. has successfully advanced its national security and economic interests in the Arctic through domestic initiatives, bilateral and multilateral treaties, regional cooperation, and U.S. membership in intergovernmental organizations focused on the Arctic.

- Part I provides an overview of U.S. national interests in the Arctic according to executive orders and policy documents developed by the Bush and Obama Administrations.

- Part II examines U.S. national security interests in the Arctic that are relevant to UNCLOS (e.g., freedom of navigation) and discusses whether accession to the convention is necessary to advance those interests.

- Part III describes U.S. economic interests in the Arctic—hydrocarbon resources, maritime traffic, and commercial fishing—and the impact, if any, that U.S. accession to UNCLOS would have on advancement of those interests.

The United States has successfully protected its interests in the Arctic since it acquired Alaska in 1867, has done so during the more than 30 years that UNCLOS has existed, and will continue to do so even if it never joins the convention. Accession to UNCLOS would have no appreciable or measurable effect on U.S. interests in the Arctic. Moreover, the harm that would be caused by the convention’s controversial provisions—e.g., revenue sharing, deep seabed mining, and mandatory dispute resolution—far outweighs any intangible benefit that allegedly would result from U.S. accession.

Part I: U.S. Interests in the Arctic

There has been consistent, bipartisan agreement over the past 20 years regarding U.S. interests in the Arctic region. In June 1994, President Bill Clinton issued an executive order on U.S. policy in the Arctic that identified U.S. interests:

The United States has six principal objectives in the Arctic region: (1) meeting post-Cold War national security and defense needs, (2) protecting the Arctic environment and conserving its biological resources, (3) assuring that natural resource management and economic development in the region are environmentally sustainable, (4) strengthening institutions for cooperation among the eight Arctic nations, (5) involving the Arctic’s indigenous peoples in decisions that affect them, and (6) enhancing scientific monitoring and research into local, regional and global environmental issues.[1]

Clinton’s directive ordered the executive branch to work with other Arctic nations to protect the Arctic marine environment from oil pollution, to conserve the region’s biological resources, and to “ensure that resource management and economic development in the region are economically and environmentally sustainable.”[2]

Fifteen years later, in the waning days of the Administration of President George W. Bush, the White House released an updated Arctic policy. President Bush’s January 2009 executive order described in greater detail how U.S. interests in the Arctic should be advanced, but the six objectives listed in President Clinton’s 1994 executive order remained the same and were repeated almost verbatim:

It is the policy of the United States to: 1. Meet national security and homeland security needs relevant to the Arctic region; 2. Protect the Arctic environment and conserve its biological resources; 3. Ensure that natural resource management and economic development in the region are environmentally sustainable; 4. Strengthen institutions for cooperation among the eight Arctic nations (the United States, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, the Russian Federation, and Sweden); 5. Involve the Arctic’s indigenous communities in decisions that affect them; and 6. Enhance scientific monitoring and research into local, regional, and global environmental issues.[3]

Several Arctic policy documents have been released during the Obama Administration: the White House’s National Strategy for the Arctic (May 2013), the U.S. Coast Guard’s Arctic Strategy (May 2013), and the Department of Defense’s Arctic Strategy (November 2013).[4] These documents describe the current Administration’s strategy to advance the Arctic interests that were outlined in Bush’s 2009 executive order. The White House’s National Strategy for the Arctic summarizes the U.S. vision for the region:

We seek an Arctic region that is stable and free of conflict, where nations act responsibly in a spirit of trust and cooperation, and where economic and energy resources are developed in a sustainable manner that also respects the fragile environment and the interests and cultures of indigenous peoples.[5]

In January 2014 the Obama Administration released a detailed “implementation plan” for the White House strategy.[6] Collectively, the Clinton and Bush executive orders and the Obama Administration’s Arctic strategy documents identify the various U.S. interests in the Arctic region and direct how those interests should be pursued.

Most of the U.S. interests listed in the Obama implementation plan and other Arctic strategy documents—e.g., maintenance of missile defense and early warning capabilities, involvement of Arctic indigenous communities in decision making, and development of military basing infrastructure—do not specifically relate to UNCLOS and so are not addressed in this paper. However, some interests identified in those documents intersect with UNCLOS provisions. The question is whether and to what extent, if any, accession to UNCLOS is essential or even helpful to advance relevant U.S. national security and economic interests in the Arctic, namely preserving freedom of navigation, securing access to natural resources within the U.S. exclusive economic zone and on the continental shelf, and managing commercial maritime traffic.

Part II: U.S. National Security Interests in the Arctic

It is of little relevance to U.S. national security interests in the Arctic that the sea ice in the region is melting. The legal status of Arctic waters does not change as sea ice melts. As polar ice melts it simply creates new areas of open water. Changes in Arctic temperature do not affect the legal regimes set forth in UNCLOS on the territorial sea, the contiguous zone, the exclusive economic zone, and the high seas. While receding ice will provide more ocean area in which military vessels may maneuver, that does not alter the legal regime governing navigation in the Arctic Ocean.

Arctic nations are committed to concord in the region, not conflict. The top national military officers from the eight Arctic nations meet annually for the Northern Chiefs of Defense (CHOD) Conference. Denmark hosted the 2013 conference in Ilulissat, Greenland, where the officers discussed issues ranging from information sharing about operational challenges in the Arctic environment, responsible environmental stewardship, and the role that the military can play in supporting civilian authorities.[7] Supplementing the annual Northern CHOD Conference are the semiannual meetings of the Arctic Security Forces Roundtable, attended by senior officers of the Arctic nations, joined by selected allies such as France and the United Kingdom.[8]

There is no reason to believe that the Arctic region will be characterized by military conflict between and among Arctic and non-Arctic nations. The U.S. Department of Defense maintains that there is a “relatively low level of threat” in the Arctic region because it is “bounded by nation states that have not only publicly committed to working within a common framework of international law and diplomatic engagement, but also demonstrated ability and commitment to doing so over the last fifty years.”[9]

The “relatively low level of threat” in the Arctic is reflected in the aforementioned Arctic policy documents. While these documents call for improvements in Arctic infrastructure, they do not call for any significant military buildup in the region. These policy documents also indicate that there is minimal overlap between U.S. national security interests in the Arctic and U.S. accession to UNCLOS.

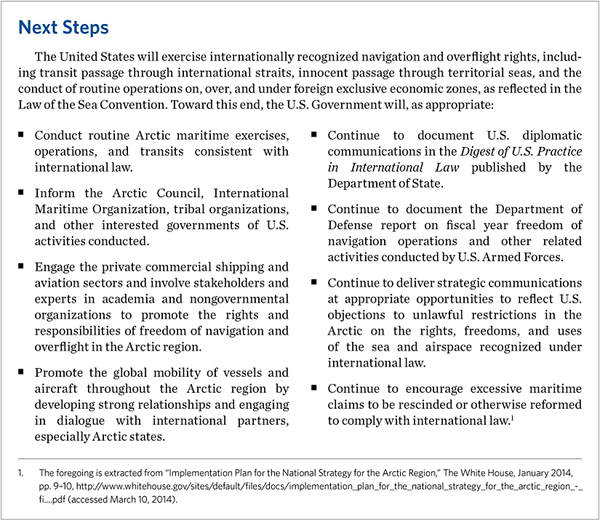

For example, the Obama Administration’s January 2014 Arctic strategy implementation plan lists six major national security objectives for the Arctic region. Only one of these objectives—“Promote International Law and Freedom of the Seas”—intersects with UNCLOS.[10] The implementation plan details the “next steps” for freedom of the seas in the Arctic. (See “Next Steps” text box.)

None of these “next steps” would be measurably advanced by U.S. membership in UNCLOS. For instance, the United States conducts maritime exercises and operations on a global scale and has done so ever since it launched a blue-water navy. Next steps such as information sharing, relationship building, and strategic communications are not contingent on UNCLOS membership and may be accomplished through any number of bilateral and multilateral means, including the Arctic Council. The next steps listed in the implementation plan are important and should be pursued by the responsible executive departments, but none of them require U.S. membership in UNCLOS.

Protecting U.S. Navigational Rights and Freedoms. The primary U.S. national security interest in the Arctic region related to UNCLOS is to preserve navigational rights and freedoms in the Arctic Ocean, which the U.S. is perfectly capable of accomplishing without joining the convention. For more than 200 years, the United States has successfully protected its navigational rights and freedoms on a global basis. U.S. membership in UNCLOS would not confer any maritime right or freedom upon the United States that it does not already enjoy in the Arctic or any other ocean.

The United States need not accede to UNCLOS in order to successfully assert its navigational rights and freedoms in the Arctic Ocean. Throughout its history, the United States has successfully protected its maritime interests without UNCLOS membership. Simply put, enjoyment of the convention’s navigational provisions—in the Arctic and elsewhere—is not restricted to UNCLOS members. Those provisions represent widely accepted customary international law, some of which has been recognized as such for centuries.

The “law of the sea” was not invented when UNCLOS was adopted in 1982 at the end of the Third U.N. Conference on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS III), but rather “has its origins in the customary practice of nations spanning several centuries.”[11] It developed as “customary international law,” which is “that body of rules that nations consider binding in their relations with one another.”[12] Although not a party to UNCLOS, the United States acts in accordance with the international law of the sea and considers many parts of UNCLOS as reflecting customary international law.

Most of the UNCLOS navigational provisions have long been recognized as customary international law. The convention’s articles regarding the high seas (Articles 86–115) and territorial waters (Articles 2–32) were copied almost verbatim from the Convention on the High Seas and the Convention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone, which were adopted in 1958. The United States is party to both agreements. Other navigational provisions such as transit passage through international straits (Articles 34–44) and archipelagic sea lanes passage (Articles 49–54) codify passage rights that existed prior to the adoption of UNCLOS, but were refined during the UNCLOS III negotiations.

The Arctic region is not special in regard to the navigational rights and maritime zones codified in UNCLOS. The same high seas freedoms that exist in the Atlantic and Pacific apply in the Arctic. The U.S. territorial sea is 12 nautical miles (nm) in breadth off the Alaskan coast, just as it is off Florida’s coast. While melting sea ice may make more areas of the U.S. exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in the Arctic accessible to resource exploitation, this does not diminish U.S. navigational rights in its EEZ one iota.

Moreover, it is irrelevant that other Arctic nations are party to UNCLOS. Those nations enjoy no more navigational rights and freedoms in the Arctic than are enjoyed by the United States and the 25 other nations that have not ratified the convention.[13] That is because all Arctic nations and almost all other nations—UNCLOS members and nonmembers alike—accept UNCLOS’s navigational provisions as binding customary law. The Restatement of the Law, Third, of the Foreign Relations Law of the United States notes:

[B]y express or tacit agreement accompanied by consistent practice, the United States, and states generally, have accepted the substantive provisions of the Convention, other than those addressing deep sea-bed mining, as statements of customary law binding upon them apart from the Convention.[14]

This has long been the U.S. position. Since the Reagan Administration, the official U.S. policy has been that UNCLOS provisions on the traditional uses of the oceans, including the provisions on navigation and overflight, confirm international law and practice.[15] Specifically, in March 1983, President Reagan released a statement on U.S. oceans policy in light of his decision not to sign UNCLOS.[16] Reagan stated that “the United States is prepared to accept and act in accordance with the balance of interests relating to traditional uses of the oceans—such as navigation and overflight” and “will recognize the rights of other states in the waters off their coasts, as reflected in the Convention, so long as the rights and freedoms of the United States and others under international law are recognized by such coastal states.”[17]

The Freedom of Navigation Program. The United States is not passive in protecting its navigational rights. It actively protects them by protesting excessive maritime claims made by other nations and by conducting operational assertions with U.S. naval forces to physically dispute such claims. The United States engaged in these activities well before the adoption of UNCLOS.[18]

These diplomatic and military protests were formally operationalized as the Freedom of Navigation (FON) Program in March 1979 during the Carter Administration.[19] The FON Program was instituted to counter attempts by other nations to “extend their domain of the sea beyond that afforded them by international law.”[20] Every U.S. Administration since President Carter has adopted and pursued the FON Program.[21] When President Reagan decided not to sign UNCLOS in 1983, he confirmed that the United States would nevertheless continue to protect its navigational rights:

[T]he United States will exercise and assert its navigation and overflight rights and freedoms on a worldwide basis in a manner that is consistent with the balance of interests reflected in the convention. The United States will not, however, acquiesce in unilateral acts of other states designed to restrict the rights and freedoms of the international community in navigation and overflight and other related high seas uses.[22]

The FON Program is relatively unknown to the public due to the fact that the vast majority of FON operations are conducted in relative obscurity, with a few notable exceptions, such as the operations in the Gulf of Sidra in 1981 and 1989 (challenging Libya’s claim of “historic waters” in the Gulf) and the “Black Sea Bumping” incident in February 1988 (challenging an excessive claim made by the Soviet Union regarding its territorial sea).

In the early 1990s, the Defense Department began to publish its operational assertions in annual reports. These reports indicate that from fiscal year (FY) 1993 to the present the U.S. Navy conducted hundreds of FON operations to dispute various types of excessive maritime claims made by 48 nations.[23] The United States has issued a limited number of FON protests regarding excessive maritime claims in the Arctic Circle, including protests of Russian “historic waters” claims in the Laptev and Sannikov Straits and Canadian regulations on transit through the Northwest Passage.[24]

The U.S. has made clear that it will act in accordance with the customary international law of the sea, including the navigational provisions of UNCLOS, and will recognize the maritime rights of other nations in the Arctic Ocean and elsewhere. When other nations assert claims contrary to customary international law, the United States actively contests such claims through the FON Program. No evidence suggests that any Arctic nation plans to hinder U.S. military mobility in the Arctic Ocean by making excessive maritime claims. Nor is there evidence that any Arctic or non-Arctic nation intends to disregard U.S. sovereignty over its territorial sea off Alaska.

While the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard strongly favor U.S. accession to UNCLOS, neither has said that they are incapable of performing their respective missions without membership in the convention. The navigational rights and freedoms enjoyed by the United States and its armed forces in the Arctic are guaranteed not by membership in a treaty, but rather through a combination of long-standing legal principles and persistent naval operations.

Part III: U.S. Economic Interests in the Arctic

The United States may successfully advance its economic interests in the Arctic—securing hydrocarbon resources, facilitating maritime traffic, and regulating commercial fishing—without accession to UNCLOS.

First, the United States has engaged in hydrocarbon exploration activities in the Arctic Ocean within its 200 nm EEZ since 1979.[25] No foreign nation has challenged the U.S. right to do so or has interfered with U.S. exploration efforts. Extending beyond the U.S. EEZ toward the North Pole is a large area of “extended continental shelf” over which the United States has jurisdiction and control to develop hydrocarbon resources to the exclusion of all other nations.

Second, to the extent that melting Arctic ice results in increased commercial shipping in Arctic waters, any resulting maritime traffic will be facilitated by international cooperation and adherence to existing multilateral agreements. Commercial shipping on the world’s oceans is largely governed by international custom and specialized maritime treaties negotiated under the auspices of the International Maritime Organization.

Finally, no commercial fishing by either the U.S. or foreign nations is permitted in the waters of the U.S. Arctic EEZ north of the Bering Strait. If in the future the United States lifts its moratorium, it is fully capable of regulating commercial fishing activities without UNCLOS membership, pursuant to existing treaties and domestic legislation.

Securing Arctic Hydrocarbon Resources. The notion that there is a “race” to exploit Arctic resources that will inevitably lead to conflict is farfetched. While many nations are interested in developing Arctic hydrocarbons, there is no indication that Russia, Canada, or any other nation—Arctic or non-Arctic—will infringe in any way on U.S. jurisdiction and control over its resources on the U.S. continental shelf, including its extended continental shelf (ECS) that extends north of the 200 nm EEZ.

Proponents of U.S. accession to UNCLOS claim that the United States cannot fully exploit hydrocarbon resources on its ECS unless it joins the convention. For example, former Senator Richard Lugar (R–IN), a longtime supporter of U.S. membership in the convention, maintained that accession is essential to establishing a valid claim to the ECS in the Arctic: “If the United States does not ratify this treaty, our ability to claim the vast extended Continental Shelf off Alaska will be seriously impeded.”[26] To treaty supporters, the right to claim resources on the U.S. ECS hinges on the approval of the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS), a special committee established by UNCLOS to review the claims made by nations to areas of ECS.

Yet history has repeatedly and definitively debunked the notion that recognition of U.S. ECS claims is contingent on U.S. membership in UNCLOS or on the approval of an international commission. To the contrary, through bilateral treaties with the Cook Islands, Cuba, Mexico, Russia, the United Kingdom, and Venezuela, the United States has successfully established its various maritime boundaries and the limits of its continental shelf and ECS.

The United States has also acted unilaterally through presidential proclamations and acts of Congress to set its maritime boundaries and lay claim to the natural resources within its maritime zones and continental shelf:

- In 1945, President Harry Truman issued two proclamations. The first, the Policy of the United States with Respect to the Natural Resources of the Subsoil and Sea Bed of the Continental Shelf, claimed jurisdiction and control over the natural resources of the U.S. continental shelf.[27] Truman’s second proclamation established a conservation zone for U.S. fishery resources contiguous to the U.S. coast.[28]

- In 1953, Congress codified Truman’s continental shelf proclamation by enacting the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act, which declared that “the subsoil and seabed of the outer Continental Shelf appertain to the United States and are subject to its jurisdiction, control, and power of disposition.”[29]

- In 1983, in the wake of his decision not to sign UNCLOS, President Reagan proclaimed the existence of “an Exclusive Economic Zone in which the United States will exercise sovereign rights in living and nonliving resources within 200 nautical miles of its coast.”[30] In 1988, Reagan followed up his EEZ proclamation by extending the breadth of the U.S. territorial sea from 3 nm to 12 nm.[31]

- In 1999, building on Reagan’s maritime proclamations, President Bill Clinton extended the U.S. contiguous zone from 9 nm to 24 nm.[32]

No nation or group of nations, much less the “international community” as a whole, has objected to or otherwise challenged the unilateral proclamations by Presidents Truman, Reagan, and Clinton. No nation disputes that the United States has a 12 nm territorial sea, a 24 nm contiguous zone, a 200 nm EEZ, or jurisdiction and control over the natural resources of its continental shelf and ECS. In fact, foreign nations recognize and respect U.S. maritime claims and boundaries, and vice versa, as long as those claims and boundaries conform to widely accepted international law, including provisions of customary international law reflected in UNCLOS.

Regarding ECS areas that appertain to the United States in the Arctic Ocean and elsewhere, the United States has indicated that it will demarcate its ECS boundary limits pursuant to accepted international law. Specifically, in November 1987, a U.S. government study conducted by the Interagency Group on Ocean Policy and Law of the Sea announced that the United States would measure its ECS in conformity with Article 76 of UNCLOS:

[T]he proper definition and means of delimitation [for the ECS] in international law are reflected in Article 76 of [UNCLOS]. The United States has exercised and shall continue to exercise jurisdiction over its continental shelf in accordance with and to the full extent permitted by international law as reflected in Article 76.[33]

In conformity with the 1987 study, the United States has successfully negotiated ECS boundary treaties with its neighbors. For example, the United States and Mexico negotiated a series of bilateral treaties on boundary lines in the Gulf of Mexico that divided an area of ECS known as the “western gap” between the two nations. The U.S. segment of the western gap ECS area has been regularly leased to U.S. and foreign energy exploration companies since 2001.[34]

In the Arctic, much of the supposed distress voiced by UNCLOS proponents stems from Russia’s vast claim of Arctic ECS that it submitted to the CLCS in 2001. The proponents incorrectly imply that Russia’s claim will result in the loss of Arctic resources that belong to the United States. According to Senator Lisa Murkowski (R–AK), for example, the U.S. failure to accede to UNCLOS would cause “a negligent forfeiture of valuable oil, gas and mineral deposits.”[35]

But the United States has not and will not “forfeit” a drop of Arctic oil to Russia or any other nation. For one thing, Russia’s claimed ECS area does not overlap any part of the U.S. Arctic ECS. To the contrary, Russia’s claim respects a boundary that the United States and the USSR negotiated in 1990—the “Baker–Shevardnadze line.”[36]

The Russian claim extends the Baker–Shevardnadze line from the Bering Strait all the way to the North Pole, likely resulting in an excessive ECS claim in the central Arctic. However, Russia’s potentially excessive claim is located to the north of the limits of the U.S. ECS area. While the Russian claim may overlap with Canada’s ECS claim, it does not overlap any U.S. ECS area.[37]

In short, there is no conflict between the United States and Russia regarding the division of Arctic resources, including hydrocarbons. Even if there were a conflict, Russia’s claim cannot be approved by the CLCS and would not be recognized by the United States (or Canada). Both UNCLOS and the CLCS’s procedural rules prevent the commission from considering any ECS area where there are overlapping claims: “In cases where a land or maritime dispute exists, the Commission shall not consider and qualify a submission made by any of the States concerned in the dispute.”[38]

The United States may object to excessive ECS claims made by any member of UNCLOS even though the U.S. is not a party to the convention. Indeed, after Russia made its 2001 claim, the United States, Canada, Denmark, Japan, and Norway each filed objections with the CLCS. In June 2002, as a result of the objections, the CLCS recommended to Russia that it provide a “revised submission” on its Arctic ECS claim.[39] Russia reportedly will make an amended submission to the CLCS at some point in the future.

The major remaining U.S. ECS boundary to be determined in the Arctic is shared by the United States and Canada. As was the case with Russia, the U.S. and Canada have approached the demarcation of this boundary cooperatively. The two nations have a mutual interest in determining the extent of their respective continental shelves and identifying their respective areas of ECS.

To that end, the U.S. and Canada have conducted a series of joint scientific operations in the Arctic to collect bathymetric and seismic data to map the continental shelf.[40] These data will enable the United States and Canada to negotiate a bilateral treaty delimiting their respective continental shelves and areas of ECS in the Arctic Ocean in the same manner as the U.S. and Mexico did in the Gulf of Mexico.

Despite dire warnings from the proponents of U.S. accession to UNCLOS, the facts demonstrate that the United States need not join the convention to demarcate areas of its Arctic EEZ and ECS, secure jurisdiction and control over these areas, and develop the hydrocarbon resources in these areas. Such demarcation has been and will continue to be conducted in cooperation with neighboring Arctic nations regardless of whether the U.S. is a UNCLOS member.

Managing Commercial Maritime Traffic. In addition to protecting its natural resources, the United States has an interest in the safe and efficient management of commercial maritime traffic in the Arctic, particularly along the Alaskan coast and through the Bering Strait. Some believe that the expected increase in traffic through the Northwest Passage (NWP) and along the Northern Sea Route (NSR) has been greatly overstated, at least in the near term. According to an April 2009 report by the Center for Naval Analysis, persistent sea ice throughout the Arctic region will continue to stymie maritime transit for some time:

To a degree, the likelihood of increases in maritime traffic in the Arctic Ocean by mid-century has been oversold.… [I]t is unlikely we will see substantial increases in cargo transit across the Arctic within the next 20 years—despite the potential distance saved on intercontinental routes.[41]

This assessment starkly contrasts with the prognostications of climate change alarmists, including NASA scientist Wieslaw Maslowski’s 2007 prediction—parroted by then-Senator John Kerry (D–MA)—that the Arctic Ocean will be “ice free” in the summer of 2013.[42] In fact, more Arctic sea ice was present in the summer of 2013 than in 2012.[43]

In addition, due to a scarcity of infrastructure to support vessel traffic—e.g., the lack of facilities to provide repairs, refueling, and provisions—it is doubtful that either the NWP or NSR will be used regularly for intercontinental transit in the near future. For instance, 41 commercial vessels used the NSR in 2011, 46 in 2012, and 71 in 2013.[44] By comparison, in 2012, an average of 47 vessels transited the Suez Canal every day.[45] Almost no commercial shipping has transited the NWP. Indeed, in September 2013, a commercial vessel—an ice-strengthened bulk freighter accompanied by a $50,000-per-day icebreaker—made the first successful commercial transit through the NWP.[46]

Nevertheless, if commercial maritime traffic in the Arctic increases, such activities would be governed by an existing regulatory structure, specifically a series of multilateral maritime treaties negotiated under the auspices of the International Maritime Organization (IMO), all of which have been ratified by the United States and the seven other Arctic nations:

- International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS). Ratified by the United States in 1980, SOLAS is “generally regarded as the most important of all international treaties concerning the safety of merchant ships.”[47] SOLAS requires that nations ensure that their ships comply with certain standards regarding construction, equipment, and operation.

- Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREG). COLREG, joined by the United States in 1977, establishes the maritime “rules of the road” to prevent collisions by adherence to uniform regulations regarding right of way, traffic separation schemes through straits, speed, sound and light signals, and related measures.[48]

- International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Seafarers (STCW). As its title implies, the STCW establishes international regulations and minimum requirements for training, qualifications, and certification of seagoing personnel. The United States joined the STCW in 1991.[49]

- International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL). Ratified by the United States in 1980, MARPOL is the “main international convention covering prevention of pollution of the marine environment by ships from operational or accidental causes.”[50]

- Convention on Facilitation of International Maritime Traffic (FAL). To reduce conflicting forms and often excessive burdens that vary from port to port, FAL codified uniform regulations for documentary requirements for arrival, stay, and departure.[51] The United States has been party to FAL since 1967.

- Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts Against the Safety of Maritime Navigation (SUA). SUA was ratified by the United States in 1995. The purpose of the convention is to compel nations to take actions, including extradition, against persons who seize ships by force or commit acts of violence against persons aboard ships.[52]

- International Convention for Safe Containers (CSC). The CSC seeks to provide uniform safety regulations for the transport and handling of freight containers.[53] The United States joined the CSC in 1979.

Due to the special nature of the Arctic and the danger of sea ice, the IMO developed “Guidelines for Ships Operating in Arctic Ice-Covered Waters” in 2002 to mitigate the additional risks of the harsh climatic conditions in the Arctic.[54] The guidelines supplement other IMO conventions, such as SOLAS, and address the special challenges of navigation, communication, emergency situations, and environmental protection in the Arctic.

Nearly all global commercial maritime traffic is regulated by the relevant IMO conventions, as explained by the IMO in a report released in January 2014:

Since 1982, formal acceptance of the most relevant IMO treaty instruments has increased greatly. As of December 2011, the three conventions that include the most comprehensive sets of rules and standards on safety, pollution prevention and training and certification of seafarers, namely, SOLAS, MARPOL and STCW, have been ratified by 159, 150 and 154 States, respectively (representing approximately 99% gross tonnage of the world’s merchant fleet).[55]

In addition to the IMO conventions and guidelines, two multilateral agreements regulate search and rescue operations in the Arctic Ocean. First, the 1979 International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue (SAR) obligates coastal states to provide search and rescue services off their coasts and encourages nations to enter into separate SAR agreements with their maritime neighbors.[56] The United States has entered into bilateral SAR agreements with a handful of nations including its two Arctic neighbors, Canada and Russia.[57] Second, in 2011, the eight members of the Arctic Council adopted a SAR agreement specific to the Arctic region. The Agreement on Cooperation on Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue in the Arctic requires each Arctic nation to establish an effective search and rescue capability, assist each other in Arctic search and rescue operations, and take other steps to address growing search and rescue needs in the region.[58] The agreement divides the Arctic region into eight sectors and assigns primary responsibility for search and rescue within each sector among the Arctic nations.

The 2011 Arctic SAR agreement and the May 2013 Agreement on Cooperation on Marine Oil Pollution Preparedness and Response in the Arctic are binding treaties that have been successfully negotiated under the Arctic Council’s auspices. Notably, the two agreements make only passing mention of UNCLOS in their preambles, where the Arctic nations “tak[e] into account the relevant provisions” of the convention.

While UNCLOS sets forth the general principles of the customary international law of the sea regarding maritime traffic, most if not all of those principles were widely accepted prior to the convention’s adoption in 1982. Additionally, when it comes to the details—the “nuts and bolts” of maritime safety and the “rules of the road” for maritime traffic—the IMO treaties, guidelines, and related agreements supersede UNCLOS.

The United States, its Arctic neighbors, and other major maritime nations are all parties to the IMO conventions on the safe operation of vessels, collision avoidance, certification of trained personnel, and virtually every other aspect of commercial maritime operations. While UNCLOS provides a general framework for maritime travel, the IMO conventions, the Arctic SAR agreement, and other maritime treaties and regulations collectively supplant UNCLOS and render U.S. membership in the convention superfluous.

Regulating Commercial Fishing. Proponents of accession to UNCLOS contend that foreign nations will exploit U.S. Arctic fisheries unless the United States joins the convention. Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s 2012 testimony in favor of accession to the convention is representative of typical pro-UNCLOS fearmongering:

And so, I think, Senator, the fact that we are an Arctic nation, we are the only Arctic nation that has not taken the step of acceding to the Convention and, thereby, being able to demarcate our Continental Shelf and our Extended Continental Shelf, is seen in Alaska as a missed opportunity and a strategic disadvantage that is increasingly going to make us vulnerable as the waters and the weather warms. And there are going to be ships from all over the world exploring, exploiting, fishing—taking advantage of what rightly should be American sovereign territory. And nobody wants to see that happen.[59]

Secretary Clinton’s testimony is mistaken in several regards. First, as discussed above, the United States has successfully demarcated its continental shelf and ECS with its Arctic neighbors, including Russia, and is in the process of doing so with Canada. Second, under international law, regardless of whether the United States ratifies UNCLOS, no foreign nation is permitted to fish within the U.S. EEZ worldwide.

Indeed, no commercial fishing—foreign or domestic—is allowed in U.S. Arctic waters north of the Bering Strait. The North Pacific Fishery Management Council’s 2009 Fishery Management Plan,[60] authorized by and developed pursuant to the Magnuson–Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, prohibits commercial fishing in the Arctic Management Area (i.e., all waters in the EEZ north of Alaska).[61] If the Arctic Management Area is opened for commercial fishing in the future, the Magnuson–Stevens Act will manage the fishing activities there just as it regulates fishing throughout the U.S. EEZ.

If the Arctic fishing moratorium is lifted and to the extent that there exist migrating stocks of fish that straddle adjoining U.S., Canadian, and Russian EEZs, exploitation of such stocks will be governed by the U.N. Straddling Fish Stocks Agreement, which the United States ratified in 1996.[62] The United States is further committed to negotiate an international agreement to prevent unregulated fisheries in the central Arctic Ocean.[63]

Secretary Clinton’s allegation that “ships from all over the world [will be] exploiting, fishing—taking advantage of what rightly should be American sovereign territory” in the Arctic is simply false. The U.S. EEZ contains approximately 3.4 million square miles of ocean. But in 2008 the U.S. Coast Guard detected a mere 81 incursions by foreign fishing vessels in the U.S. EEZ.[64] While such illegal fishing has occurred and will continue to occur in the vast U.S. EEZ, Secretary Clinton’s imagined world of foreign fishing vessels running rampant through U.S. Arctic waters is baseless. Like on other matters in the Arctic, curbing illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing is done cooperatively with other Arctic nations, including Russia.[65]

In sum, the pursuit of natural resources and the management of maritime traffic in the Arctic is characterized by cooperation and coordination among Arctic nations, not conflict. The idea that economic conflict in the Arctic is inevitable is a myth peddled by proponents of U.S. accession to UNCLOS.

In reality, there is no correlation between the advancement of U.S. economic interests in the Arctic and U.S. accession to UNCLOS. The United States has negotiated and is negotiating with its Arctic neighbors the boundaries of their respective maritime zones and continental shelves. It is unthinkable that a foreign nation would attempt to explore or drill for oil within the U.S. EEZ or on the U.S. ECS without U.S. consent. Nor would any foreign nation feel that it could engage in illegal commercial fishing in the U.S. EEZ with impunity. Finally, to the extent that commercial maritime traffic increases in the Arctic in the decades ahead, such traffic would be governed by a series of specialized maritime treaties adopted under the auspices of the IMO.

Intangible Benefits Outweighed by Serious Detriments. Simply no evidence at present indicates that U.S. accession to UNCLOS would appreciably affect the advancement of U.S. national interests in the Arctic region. No foreign nation has attempted to exploit Arctic natural resources (e.g., hydrocarbons, fish, and minerals) that belong to the United States. Nor has the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard been prohibited from performing any mission in the Arctic Ocean due to U.S. nonmembership in the convention.

Nevertheless, some proponents of U.S. accession maintain that joining the convention would assist the United States in attaining its interests because it establishes a legal framework for virtually all maritime issues and codifies widely accepted international law. It is challenging to assess with any certainty the merits of such vague claims promising intangible benefits.

The intangible benefits, if any, that may or may not come from having a “seat at the table” at the UNCLOS annual meetings of states parties is by its nature difficult to prove or quantify in any meaningful way. The agenda of these conferences in New York is concerned with nonsubstantive matters—e.g., the nomination, election, and remuneration of representatives to the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea and the CLCS, budgetary matters, and credentialing for conference attendees.[66]

No great debates are taking place at these annual meetings regarding maritime hydrocarbon resources, excessive maritime claims, proper and improper activities within the EEZ, commercial fishing, development of the continental shelf, or seemingly any other substantive matter dealing with the law of the sea in the Arctic or elsewhere.

Many UNCLOS proponents maintain that the United States would benefit from joining the convention because it could nominate a U.S. national to the CLCS. These proponents imply that a U.S. national on the CLCS will directly benefit the United States and help to advance its ECS claims. Secretary Clinton, for example, testified, “We need to be on the inside [of the CLCS] to protect and advance our interests.”[67] Yet any U.S. national elected to the commission serves in his “personal capacity,” meaning that he cannot defend or otherwise represent the views or interests of the United States on any U.S. ECS claim.[68] Additionally, the substantive analysis of any ECS claim made by the United States would be conducted by a seven-member subcommission on which the U.S. member may not sit.[69]

Regardless, the supposed benefits of electing a U.S national to the CLCS and having a “seat at the table” at annual UNCLOS meetings do not justify U.S. accession to the convention. These benefits, such as they are, should be weighed against the detriments of joining the convention:

- If the U.S. accedes to UNCLOS, Article 82 would require the U.S. to transfer royalties generated from hydrocarbon production of the U.S. ECS to the International Seabed Authority for redistribution to developing and landlocked countries. Since the value of the hydrocarbon resources lying beneath the U.S. ECS may be in the trillions of dollars, the amount of royalties that the U.S. Treasury would be required to transfer to the Authority would be significant.[70]

- U.S. accession to UNCLOS would empower the International Seabed Authority to control U.S. access to the deep seabed and regulate the manner in which deep seabed minerals are mined. Proponents of U.S. accession contend that by failing to join the convention the United States is forbidden from mining the deep seabed. However, no legal barriers prevent U.S. access, exploration, and exploitation of deep seabed resources. The United States has long held that U.S. corporations and citizens have the right to develop the resources of the deep seabed and may do so whether or not the United States accedes to UNCLOS.[71]

- U.S. accession to UNCLOS would expose the U.S. to lawsuits on virtually any maritime activity, such as alleged pollution of the marine environment from a land-based source or through the atmosphere. Regardless of the merits of a case, the U.S. would be forced to defend itself against every such lawsuit at great expense to U.S. taxpayers. Any adverse judgment rendered by an UNCLOS tribunal would be final, could not be appealed, and would be enforceable in U.S. territory.[72]

A cost-benefit analysis of UNCLOS vis-à-vis U.S. Arctic policy establishes that accession would not materially advance any U.S. national interest in the region and that the costs would outweigh any intangible benefits of accession. The U.S. has already secured and continues to pursue its national security and economic objectives in the Arctic through bilateral and multilateral treaties that are not saddled with UNCLOS’s baggage. U.S. membership and participation in multilateral organizations—such as the Arctic Council, the Northern Chiefs of Defense Conference, and the Arctic Security Forces Roundtable—provide the necessary “seat at the table” to secure U.S. national interests in the region in the years ahead without accession to a deeply flawed treaty.

—Steven Groves is Bernard and Barbara Lomas Senior Research Fellow in the Margaret Thatcher Center for Freedom, of the Kathryn and Shelby Cullom Davis Institute for National Security and Foreign Policy, at The Heritage Foundation.