Abstract: President Obama has released his fiscal year 2011 budget request. While the budget increases funding for the Department of Homeland Security by 2 percent, and while the Obama Administration continues to make cyber security, aviation security, and E-Verify top fiscal priorities--the budget fails to adequately align spending to the department's stated missions. The Coast Guard, WMD preparedness, and immigration enforcement/border security are just some essential aspects of a national security strategy that remain underfunded, while other programs--proven unsuccessful--have received fattened budgets. Heritage Foundation national security analyst Jena Baker McNeill maps out mismatched spending--and provides some direction for smart funding of the department's essential missions.

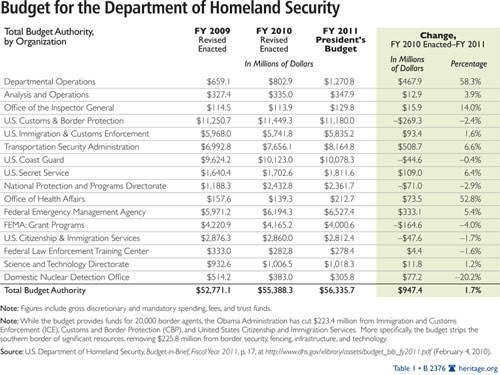

On February 1, 2010, the Obama Administration released its fiscal year (FY) 2011 budget request. The President's budget of $56.3 billion for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) represents a 2 percent increase from FY 2010.[1] The Administration continues to make cyber security a top priority, while requesting additional funds for airport security, bio-surveillance, and the E-Verify online employment-verification portal, among other initiatives.

Simply adding more money to the DHS top line, however, is not a reliable indicator that the department is using its resources wisely. One way to assess the budget is to examine how closely allocated dollars align with the Department of Homeland Security's mission. In this way, the budget fails to focus sufficiently on creating a homeland security enterprise"--bringing together all assets, from state and local governments, to the private sector and private citizens--into a cohesive framework, able to prepare for, prevent, and respond to terror attacks and natural disasters. At the same time, the new budget request disregards much-needed reforms for immigration services and enforcement as well as security at the U.S.-Mexican border-- cutting the overall immigration services and enforcement budget from $20.05 billion to $19.8 billion. Finally, the Administration focuses too heavily on the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) airport-passenger screening line in its efforts to prevent terror attacks. Preventing terror attacks is a task best accomplished by initiatives aimed at stopping terrorism in its earliest stages through robust information-sharing and quality intelligence-gathering.

Fulfilling its missions and putting in place a quality budget is fundamental to the growth and success of the DHS as well as the security of the nation. As Congress moves through the budget process, it should fill these gaps and make the budget more representative of the DHS mission.

The Homeland Security Budget

Opening with a budget of $42.4 billion in FY 2003, the Department of Homeland Security's funding has been growing modestly since then.[2] These increases have been appropriate given the resources required to bring a new department up to speed, including personnel, infrastructure (including a new headquarters facility), and other critical investments. This growth has remained relatively constant in the transition from the Bush Administration to the Obama Administration, with the FY 2010 budget request, the Obama Administration's first, coming in at $55.1 billion, an increase of 5 percent from the FY 2009 budget.[3]

One of the lessons of 9/11, and arguably the impetus for the creation of the Department of Homeland Security, was that money alone did not make the U.S. capable of responding to disasters or terror attacks. Security was a priority before 9/11, and money was spent then, too. In fact, between FY 1995 and FY 2001, the federal government increased homeland security spending in the regular annual appropriations bills from $9 billion to $16 billion, an increase of 60 percent."[4]

But what changed with the creation of DHS was that there would now be a federal agency to ensure that the federal actors coordinate with each other, and that the government allows states and localities, tribal actors, as well as the private sector and private citizens to participate in the nation's security.[5] As a result, the department retains the key task of developing the homeland security enterprise.

Assessing the DHS Budget. Maturing and strengthening the homeland security enterprise requires the DHS missions to be representative of the challenges facing the department, which can serve as a useful indicator of whether the President's budget is allocating money in the right areas. The mission serves to delineate what should be the strategic priorities of DHS, as opposed to politics or other bureaucratic obstacles that often dilute good fiscal policymaking.[6] There is no doubt that the complex mission of DHS requires the department to be well resourced. The President must be careful that budget allocations support, not undermine, this enterprise. The DHS mission can be broken down into five focus points:

- Preventing terrorism and enhancing security;

- Safeguarding and securing cyberspace;

- Ensuring resilience to disasters;

- Securing and managing our borders; and

- Enforcing and administering U.S. immigration laws.

While not a perfect assessment of DHS performance, examining this mission in depth can give a general idea of whether each role is receiving adequate resources, and whether, in certain situations, DHS has committed too much or too little attention to a particular function.

Maturing and Strengthening the Homeland Security Enterprise

The overall goal of DHS is to lead a unified national effort to secure America, commonly referred to as the homeland security enterprise. This mission gets to the heart of what DHS should be doing to make America safer. First responders, along with state and local governments, will typically be the first to react within their own communities in the event of a disaster or catastrophe."[7] The private sector, for its part, as well as private citizens, has often served as resource distributor and default emergency responder when the government was simply unable to do so. Retail-chain giant Wal-Mart, gave $20 million in cash donations, 1,500 truckloads of free merchandise, food for 100,000 meals and the promise of a job for every one of its displaced workers" in the wake of Hurricane Katrina.[8] In fact, Wal-Mart had a better logistics process and more nimble disaster planning" than the government, helping to save lives in the hurricane's immediate aftermath.[9] A comprehensive homeland security strategy requires an equally comprehensive effort from all levels of government, the private sector, individual communities and private citizens."[10]

DHS actions related to this mission have often centered on the Homeland Security Grant Program.[11] The goal of the grant program is to help states and localities build their own capabilities to respond to terrorism and natural disasters. The problem with this approach, however, is that the program has become the pork barrel of homeland security. Instead of focusing money on needed technologies and infrastructure, or on the highest-risk locations,DHS often spreads the money out equally--shortchanging high-risk jurisdictions. State and local governments have often lined up for the dollars, and federal elected officials have been all too willing to give them a share with little regard to actual need.[12]

The Urban Area Security Initiative (UASI), a component of this grant program, is an example of this problem. In FY 2008 there were 42 UASI jurisdictions that could receive these grant monies--meant to serve large, urban areas where a terrorist attack would have catastrophic national consequences."[13] DHS, however, has continued to increase the number of urban areas that are eligible for UASI funds, now totaling 60, without allocating additional monies, diluting the pool of resources further, and under-sourcing America's urban areas.[14]

The FY 2011 budget request simply furthers this problem and makes states and locals less empowered than ever before. DHS has stated it intends to provide $4 billion in state and local grant program funds. The first problem is that despite the increase in funding, UASI grant dollars remain the same (as does the number of eligible cities). Furthermore, DHS makes it seem like it is increasing the UASI budget by inserting $200 million for security at terrorism trials for Guantanamo detainees that take place in the U.S. (funds that would not go to urban areas, unless these jurisdictions housed these detainees).[15] These terror trials have no relationship to the purpose of UASI--whose grants are intended to build capabilities in an urban area, not to supply money for specific projects.

The new budget request even seems to change its grants terminology, increasing the likelihood that grants will be spent in an inefficient manner. The term risk-based" has long been the standard for the allocation of grant spending--meaning that the risk of a terror attack or other disasters should determine the decisions about which jurisdictions receive which amount of resources. While DHS has not been allocating most grants on the basis of risk, the standard was correct and should have been enforced bythe department. The new budget documents, however, reword the standard to risk-informed," which implies that information about risk will be available, but will not determine grant allocations.[16] Given that $4 billion will now be spent in a risk-informed" manner, it will likely bring even more inefficiency to the current system.

The right approach to funding disaster preparedness will recognize the legitimate role that federal dollars can play in boosting capabilities at the state and local levels while allowing states and localities to be on a more even playing field with their federal counterparts, specifically the Department of Homeland Security.The need for such equality downplays the need for the grant structure and invites another approach, such as the use of cooperative agreements--where the federal government and the states can sit down as true and equal partners and negotiate outcomes at the beginning, including covering programmatic and financial oversight requirements, and then direct funds to achieve those desired outcomes without the need for yearly applications."[17]

REAL ID. One of the changes in the FY 2011 budget request is the consolidation of separate grant programs under the Homeland Security Grant Program (HSGP) umbrella, including grants to states for REAL ID implementation.[18] REAL ID (required under a 2005 congressional mandate) sets national standards for the issuance of driver's licenses.[19] Moving thesegrants under the HSGP umbrella makes it less likely that states will use grant dollars to implement REAL ID--despite a need to make driver's licenses more secure (as a tool to fight identity theft, terrorism, and illegal immigration). Given that the Administration has already started to roll back REAL ID--including a push for legislation (the Providing for Additional Security in States' Identification, or PASS ID Act) that would effectively repeal many of the key provisions of the mandate, REAL ID is unlikely to be a priority for DHS in FY 2011. In fact, FY 2011 budget documents emphasize the department's intention to push Congress to pass PASS ID, which likely would be less rigorous."[20] Furthermore, there is no reflection in the budget numbers that states and localities will receive any additional monies for implementation of REAL ID or that Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano intends to follow through with her self-imposed compliance deadline of May 11, 2011.

Law Enforcement. Another major impediment to the creation of a national strategy to fight terrorism involves the federal interaction with state and local law enforcement. For all of its talk about the need for interaction with state and local officials, the Obama Administration continues to shy away from making use of their assistance, and has taken steps to stop their participation in a number of areas, specifically enforcement of immigration laws.[21]

This is disappointing given the fact that state and local law enforcement resources far exceed those of the federal government. For example, states and localities employ over 1.1 million [law enforcement] officers, compared to the roughly 25,000 agents working for the Federal Bureau of Investigation and Immigration and Customs Enforcement."[22] This means that these law enforcement entities can be tremendous force multipliers for the federal effort. Such a move makes sense given that constitutionally, states and localities are the proper leads on domestic security issues."[23]

State and local law enforcement can be useful in both counterterrorism and immigration enforcement and border security. One of the programs that has received scant attention in budget documents is the 287(g) program--through which the U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) offers to train state and local law enforcement officers as ICE agents--identifying illegal aliens for deportation. This program has been quite successful, getting criminal aliens off the streets and out of the country.[24] Yet the Obama Administration, facing serious political pressure from the ACLU and anti-immigration law-enforcement groups, has made changes to this program that are likely to decrease participation by states and localities, including new requirements that restrict the use of 287(g) checks to aliens involved in felonies. Neither the FY 2011 budget request nor accompanying documents make mention of 287(g)as one of the department's programmatic priorities.

Simultaneously,information-sharing fusion centers" for state, local, and federal law enforcement officials, touted heavily by Secretary Napolitano in the FY 2010 Budget in Brief, which accompanies the budget request, as a much-needed tool to fight terrorism (including a FY 2010 request for full support and staffing" for 70 centers), also received little attention in the FY 2011 request.[25] In fact, the FY 2011 documents made very few references to the role of state and local officials in intelligence gathering and analysis--a move that is contrary to the mission of a unified effort. What makes these state and local law enforcement officers so vital is their relationships with their communities--where they receive leads and other tips that can help stop terrorist attacks in their earliest stages.

1) Preventing Terrorism and Enhancing Security

The nearly successful bombing of an American passenger plane on Christmas Day by Nigerian Umar Farouk Abdulmuttallab was a reminder of the need for the U.S. Department of Homeland Security to prevent terrorism and enhance security. Therefore, it is logical for the Administration to demonstrate its commitment to stopping such attacks in its budget request.

However, the Obama Administration's budget makes a mistake too often repeated by the previous Administration and in Congress--focusing monetary investments at the TSA passenger screening line.[26] Specifically, the new budget provides $549.5 million for the installation of 500 additional Advanced Imaging Technology Screening machines (bringing the total number of full-body scanners in the U.S. to 1,000), as well as for 255 new officers to operate these scanners, $20.2 million for behavior-detection officers, and $95.7 million for mission support"--including training, uniforms, and funding for 5,355 Transportation Security Officers (TSOs) and screening managers. The scanners and accompanying staff are part of a broader package in the budget totaling $769 million for passenger aviation security (including 275 more canine detection teams at $71 million and $60 million for 800 portable explosive-trace detection devices).[27]

Full-body scanners received waves of media attention after the Christmas Day plot, when the standard metal detectors failed to detect a bomb hidden in the underpants of Abdulmutallab. Full-body scanners, as well as other technologies and resources like canine teams, can be used to help a TSA agent or airport employee spot suspicious items on passengers. The problem is that by the time a would-be bomber has reached an airport screening line, such an attack is significantly more difficult to stop. Focusing efforts at the airport is challenging from a number of angles:

- Terrorists adapt. Terrorists have demonstrated their ability to evade technology. In fact, when the 9/11 attackers used box cutters to bring down the airplanes they hijacked, box cutters were perfectly legal under existing security rules. Furthermore, regardless of the sophistication of the piece of technology, if you can collect the information on how it works and what its technical parameters are, then that machine is not going to deter a [sophisticated] terror operation."[28]

- Humans--and machines--are not perfect. Full-body scanners, cameras, and other technologies are only as effective as the screener operating the equipment. Agents must review the scans, correctly recognize prohibited items, and physically stop a suspect from making his way through the screening line. Furthermore, full-body scanners themselves have limitations. The advanced imaging scanners would not have caught substances hidden in a bodily orifice," for instance.[29]

- Terrorists change targets. Out of the at least 28 terror plots disrupted since 9/11, not all were aimed at airplanes. Iyman Faris, a naturalized U.S. citizen, was arrested in 2003 for a plot to use blowtorches to collapse the Brooklyn Bridge. In 2009, Najibullah Zazi was arrested in an attempt to blow up the New York subway with an acetone bomb. In fact, there have been multiple plots aimed at bridges, subways, and other transportation systems. Simply stopping terrorists from boarding a plane only goes so far in countering terrorism because terrorists will simply change their strategy.

All of these challenges make the case for a robust counterterrorism program that can stop terror attacks in the earliest stages as well as provide an accurate picture of the threats facing the nation. Doing so requires extensive communication with state and local law enforcement officials (making a unified effort even more imperative) as well as the right kinds of counterterrorism tools. One of DHS's tools is intelligence gathering and analysis. DHS Operations and Analysis, the directorate charged with DHS activities in this domain, including support for fusion centers, received an entire budget-request increase of only $12.9 million (compared to the $769 million specifically spent on passenger aviation security measures).[30]

The budget does make two key investments that are important for aviation security. The first is the decision to allocate funds for additional air marshals on international flights. Air marshals provide another layer of deterrence against terrorism. Furthermore, one way to use this FY 2011 money even more effectively would be to give air marshals real-time access to databases (both while on the ground and in the air) which offers the additional capacity to screen flight manifests for suspicious passengers."[31]

Second, the Administration has requested $40 million and 74 full-time employees to manage international programs at 15 of our 19 existing [TSA] offices around the globe."[32] These programs help to improve the security practices of other countries--making it less likely that a terrorist will gain access to the United States through an inbound international fight. The DHS is making the right decision to put these programs in high risk areas such as the Middle East and Africa" where security challenges are significant.[33]

Weapons of Mass Destruction. The Commission on the Prevention of Weapons of Mass Destruction Proliferation and Terrorism (WMD Commission) released a report card" in late January that gave the Obama Administration an F" for progress on protecting Americans against weapons of mass destruction.[34] The Department of Homeland Security has a major role in preventing and preparing for such an attack, as do several other agencies. The report specifically emphasizes the role of DHS in preparedness, response, and surveillance. The FY 2011 budget does provide funds for BioWatch--an early warning system to help detect pathogens indicating a bioterrorism attack, as well as $61 million for radiation detection equipment at seaports, land border crossings and airports."[35] Yet, the Domestic Nuclear Detection Office (DNDO), whose role it is to improve the nation's capability to detect and report unauthorized attempts to import, possess, store, develop or transfer nuclear or radiological material for use in terrorism," has experienced cuts of around 77.2 million.[36] The WMD Commission has recommended that DHS specifically work with a consortium of state and local governments to improve preparedness in the event of WMD attack."[37] Again, however, the department's ability to do this hinges on its ability to maintain a robust homeland security enterprise--a goal that has been left unfulfilled in the FY 2011 budget.

2) Safeguarding and Securing Cyberspace

The Obama Administration has rightly focused on cyber security as one of its major homeland security priorities. Attacks on cyber infrastructure, both in the private sector and federal government, will continue to pose a major security challenge in FY 2011. But despite $75.1 million in cyber security funding in FY 2010, the Administration made little progress on achieving its goal of enabl[ing] DHS to develop and deploy cyber security technologies to counter on-going, real world national cyber threats and apply effective analysis and risk-mitigation strategies to detect and deter threats."[38] Melissa Hathaway, the would-be cyber czar named by the President, left just six months into the job. While she cited personal reasons for her departure, her announcement was followed shortly by several publicly damaging cyber security efforts in Congress, including public outcry over the Cyber Security Act of 2009, which led Americans to believe that the President would be given the ability to shut down the Internet at will.[39]

These roadblocks must be resolved as the Obama Administration enters a new budget cycle. While efforts in Congress cannot necessarily be controlled by the President, his leadership can make the difference in policymaking. For FY 2011, the Obama Administration has requested $364 million in cyber security dollars, including funding to support the Comprehensive National Cyber Security Initiative, which works to create policy and strategy and guidelines to secure federal [cyber] systems."[40] Such a monetary commitment is indeed needed, and the Obama Administration should push for some of this money to be spent on education and certification for cyber professionals as well as extensive research.

3) Ensuring Resilience to Disasters

Perhaps one of the most prominent examples of the need for a truly national homeland security enterprise, premised on the principle of resiliency, to adequately respond to the threats and hazards to the nation, is Hurricane Katrina. As evidenced in the wake of the hurricane, first responders are the most critical players in the first 24 to 72 hours after a disaster--bringing necessary resources, food, and shelter to those afflicted. DHS cannot accomplish its mission of responding adequately to these threats and hazards without the first responders, who do not work for the federal government. But all too often, the solution to disaster response has been to emphasize a federal solution instead of empowering states and localities to respond effectively without federal interference.

The grant problems that hamper America's ability to stage a unified effort to secure America are the same challenges that affect the country's ability to respond to threats and hazards to the nation. Some grant programs that have proven to be ineffective have continued to grow in budget after budget. The Staffing for Adequate Fire and Emergency Response (SAFER) grant program, for instance, was created in 2001 to reduce fire casualties. Congress appropriated around $5.7 billion in fire grants from FY 2001 to FY 2009.[41] The Obama Administration requested a 100 percent increase in these grant dollars for FY 2010--asking for $420 million.[42] The Heritage Foundation found in a recent study that these grants fail to reduce firefighter deaths, firefighter injuries, civilian deaths, or civilian injuries."[43] Despite this lack of effectiveness, the SAFER grant program continues to receive large budgetary commitments--including a FY 2011 request of $305 million in funding.[44] These funds could certainly be used elsewhere to increase the effectiveness of other response programs.

The Transit and Port Security Grant Programs, funded in the FY 2011 request,are roughly as ineffective as the SAFER grant program. The Department of Homeland Security has experienced tremendous criticism over the use of grant money by port operators, including a 2005 Inspector General report that highlighted the use of appropriated funds for fencing and other infrastructure upgrades that were not intended under the program. There is no indication that this problem has improved. Yet, the Obama Administration's FY 2011 budget request would provide another $600 million in these types of funds.[45] At the same time, the Obama Administration decreases the number of Maritime Safety and Security Teams (MSSTs), created to patrol critical infrastructure, perform counter terrorism activities, enforce laws aboard high interest vessels, and respond to unanticipated surge operations (e.g., mass migration response, hurricane response, terrorist attack, etc.)," which have been successful, even assisting in disaster recovery in Haiti.[46]

For all of the attention paid to these grant programs, significant roadblocks to response capabilities remain untouched in the FY 2011 budget. One of the areas in which the WMD Commission emphasized needed reforms is in emergency medical care. The recent H1N1 flu scare also focused attention on lack of medical preparedness by demonstrating that a communicable agent could be used easily in a bioterror attack and would spread rapidly without the right strategy and framework in place. While the response to H1N1 was generally good, a more potent biological agent that requires millions of Americans to receive emergency care would grossly overwhelm the system. In fact, over three-quarters of emergency physicians reported in the annual American College of Emergency Physicians' survey that their hospital does not have the surge capacity to respond effectively to an epidemic illness or an act of terrorism."[47] While this is not a problem limited to DHS--the Department of Health and Human Services often takes a lead role--DHS certainly has some responsibilities in this matter. The FY 2011 budget request made cuts to nearly every program in the Office of Health Affairs (OHA), the DHS office that coordinates medical readiness activities. The only program to receive sustained or greater levels of funding within OHA was the BioWatch program.[48]

4) Securing and Managing Our Borders

One of the major missions of DHS is to secure U.S. borders and manage the flow of incoming and exiting visitors. This mission has multiple dimensions. America continues to battle a serious illegal immigration problem within its borders. This problem is a direct result of security gaps at the southern border and ineffective immigration enforcement regimes that encourage the abuse of visa policies. The illegal crossings at the U.S.-Mexican border are accompanied by growing cartel violence and the smuggling of drugs, weapons, and people. At the same time, legitimate economic interests and burgeoning trade create a need for an efficient and well-functioning border.

The Bush Administration had begun the process of securing the southern border through its Secure Border Initiative. However, in recent weeks, Secretary Napolitano has all but halted SBInet, a component of the Secure Border Initiative that provides a virtual fence, ordering a review of the project before it can move forward. The Secretary did little to ease concerns by failing to provide a new strategy for the smaller border technologies that might help fill the security gaps at the southern border. Furthermore, Secretary Napolitano has allocated funds for northern-border projects which seem to be more of a distraction from southern-border cuts than needed budget line items.

The internal enforcement side of the FY 2011 budget request seems to be lopsided in favor of a single program--E-Verify, a voluntary program that provides a free online portal for employment verification. This focus seems to fall in line with the recent DHS policy of employer-specific immigration enforcement measures. The budget dedicates 338 full-time employees, as well as $103.4 million in monies to E-Verify.[49] E-Verify is a good program and should be supported, but the narrow focus on it raises concerns about whether it will be the end-all of the Obama Administration's internal enforcement strategy. Social Security No-Match workplace checks, among other initiatives, are vital tools in this internal enforcement effort. However, the only other highlighted immigration-law enforcement allocation is a $146.9 million request for the Secure Communities program.[50] This program--which helps ICE prioritize criminal aliens for removal on the basis of national security risk--largely shifts the responsibility for enforcing immigration laws back on the federal domain.

In terms of promoting tourism to the United States, the budget phases out funding for the US-VISIT biometric exit program. This mandate, put in place by Congress in 2007, required DHS to biometrically track the exit of all foreign visitors from the United States by this past summer. DHS has released pilot results, but has yet to determine a specific solution to the mandate--waiting for Congress to choose the course. This stalemate had a tremendous impact on the growth and expansion of the Visa Waiver Program (VWP), a vital public diplomacy and tourism tool, making the need for a decision by Congress all the more imperative. Not only does the budget fail to focus on welcoming immigrants and visitors--it takes an additional swipe at trade. The FY 2011 request cuts $74.8 million from the Automated Commercial Environment program, meant to improve the flow of information between Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and the trade community.

Coast Guard. The FY 2011 Homeland Security Budget-in-Brief produced by DHS outlines what the department touts as major financial commitments to the Coast Guard; for instance, $538 million for the construction of a fifth National Security Cutter as well as $240 million to construct four Fast Response Cutters.[51]

The overall budget of the Coast Guard, however, has dropped by $44 million.[52] While increases in surface and air assets are welcome additions to the current fleet, the number of worn-out, inadequate, and outdated ships and aircraft (many of which are not even operational) make these FY 2011 modernization dollars a drop in the bucket. As one National Security Cutter is added to the fleet, four High Endurance Cutters will be decommissioned. And the budget adds nothing for icebreakers--which are very old. Other nations are investing rapidly in new and improved icebreakers as part of their own Arctic initiatives.

Despite a significant increase in responsibilities, from drug interdiction and counterterrorism to environmental cleanup and border security, the Coast Guard has been continuously shortchanged on resources. Most of the FY 2007 request for $950 billion for Coast Guard modernization was cut by Congress. Given that the Coast Guard as been drastically underfunded for the last decade, any decrease in personnel or operations is simply unwarranted. The Coast Guard needs a tremendous financial commitment in order to keep up with its almost exponentially growing missions.

5) Enforcing and Administering U.S. Immigration Laws

Ensuring that America is a welcoming place for legal immigrants, visitors, and trade is important for keeping American society vibrant and prosperous. At the same time, it is vital that the U.S. enforces its immigration laws and establish disincentives to illegal south-to-north migration.

The Obama Administration has engaged in significant rhetoric indicating that it remains committed to border security and internal enforcement of existing immigration laws. Secretary Napolitano has gone so far as to indicate that the Obama Administration is taking a harder line on illegal immigration than the preceding Administration. She recently stated that we've also shown that the government is serious and strategic in its approach to enforcement by making changes in how we enforce the law in the interior of the country and at worksites."[53] She continues to claim that we have replaced old policies that merely looked tough with policies that are designed to actually be effective."[54]

This rhetoric, however, has not been matched by policy. The Administration has been gutting workplace-law enforcement programs like Social Security No-Match (which informs employers when they have high numbers of employees with mismatched SSNs) and 287(g), while decreasing random workforce employment checks (aimed at identifying illegal immigrants working in U.S. businesses)or making them less effective. Nor is there serious financial backing in the FY 2011 budget request. The Obama Administration has cut $223.4 million from Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Customs and Border Protection, and Citizenship and Immigration Services.[55] More specifically, the new budget strips the southern border of significant resources, cutting $225.8 million from border security, fencing, infrastructure, and technology funding. Some of these cuts may be warranted, as the fencing has largely been completed; however, these actions, taken together, seem to indicate a policy shift.

The ability to remain welcoming to legal immigrants requires tremendous improvements in the funding structure of the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). The USCIS fee-for-funding model, which requires the agency to fund itself entirely on immigration fees paid bythose seeking entrance to the United States, is a significant challenge--shortchanging the agency in terms of much needed infrastructure and technology investments that can drastically improve visa processing and services.

Yet, the Obama Administration's budget avoids these challenges--and sets aside very little money for resources to improve the way that USCIS does business. In fact, the USCIS budget decreases by $47.6 million. The only budgetary highlight of the FY 2011 request pertaining to USCIS is $18 million to promote citizenship through education and preparation programs...and expansion of innovative English learning tools."[56] Promoting citizenship is certainly a worthwhile goal; however, improving the processing of visas and making the citizenship process more efficient must also be a priority for the Administration.

The immigration services and enforcement budget is actually quite reflective of the Obama Administration's attitude toward immigration reform. The new budget focuses enforcement efforts on the employers, while the Administration has dramatically slowed the identification and deportation of all illegal aliens except serious criminals, while pushing aggressively for amnesty as the cornerstone of the Administration's comprehensive immigration-reform agenda. The Administration continues to push large amounts of dollars into the E-Verify program in order to look tough on enforcement, while decreasing enforcement measures that might impede a mass legalization effort.

Overarching Considerations

While the various components of DHS experience their own unique budgetary challenges, there are specific hurdles that have an impact on all components, and on their ability to fulfill their missions, including:

Research. The Science and Technology Directorate of DHS took a hit in funding in the FY 2011 budget request. In fact, while the budget as a whole receives an $11 million increase, there are near across-the-board spending cuts to research, with decreases in border and maritime research, chemical and bio-security research, and human factors research, among other cuts. The only three areas that seem to be spared these cuts were the explosives, radiological/nuclear, and innovation divisions. While the Science and Technology Directorate does not receive a large amount of money, its job is so fundamentally important to all parts of DHS--by providing research and technologies to counter multiple threats and all of the missions--that it should be fully supported in the budget through targeted financial commitments.

Interagency Relationships. The budget often classifies homeland security priorities on a department basis. Of course, homeland security spending often bleeds into other federal agencies. The Department of Health and Human Services, the Department of Defense, and other agencies have a major impact on how well DHS can achieve its missions. DHS needs to work out these interagency relationships, which are often the source of infighting and power struggles.

Contractor Avoidance. In 2009, Secretary Napolitano launched what she calls a balanced workforce strategy." The goal of this strategy was to decrease use of contractors both in current and future DHS operations.[57] This is certain to have an impact on future budgets, requiring significantly more manpower. Contractors can play a very good role and can, if managed appropriately, decrease the cost of doing business for DHS. Secretary Napolitano should exercise this effort with a careful hand.

Achieving the DHS Mission

The Department of Homeland Security has significantly further to go in strengthening and maturing the homeland security enterprise. While the budget does take some needed steps in terms of improving the Coast Guard--a fundamental player as the law enforcer of the seas--it simultaneously drains key personnel funds at a time when the Coast Guard is experiencing more and more demands for its services. Finally, the budget request disregards key programs needed for immigration services and at the nation's borders that can help solve the nation's serious illegal-immigration problems.

The onus is on now Congress to ensure that the FY 2011 budget fills these gaps. Throughout the process, Members must be careful not to lose sight of the overarching goal of creating a robust homeland security enterprise. Congress should:

- Fill budget gaps. Congress should use this budget process as a means of filling the security gaps in the budget. It should use the missions of the Department of Homeland Security as a rubric for which levels of spending are appropriate. This may mean decreases in areas where DHS has overreached or has taken on roles best suited for state and local governments or other outside actors.

- Pass an authorization bill. Congress has yet to pass a department-wide authorization bill forthe Department of Homeland Security. This bill is critical to the maturity of DHS by creating a statutory structure that would increase legislative stability and help to improve congressional oversight of the department.[58]

- Reform Oversight of DHS. Currently, 86 committees and subcommittees have jurisdiction over the department. As a result, Members on committees with little emphasis on homeland security often press for what is best for their constituencies, not what is best for security. Congress should consolidate oversight into four standing homeland security committees.[59]

- Re-examine grant spending. DHS and Congress need to take a look at the current grant structure. If they choose to retain the grant framework, they must ensure that they are basing allocations on risk. Grants are not about merely giving money away, they are about empowering states and localities to take action on their own and having the capabilities to do so. A good first step would be to conduct a national capabilities assessment to figure out the gaps that need to be filled. Also, eliminating state minimums and maximums on grant allocation and requiring matching state contributions could ensure that states do not supplant state homeland security funding with federal grants."[60]

- Resist earmarks. Congress should vote on the Administration's FY 2011 homeland security budget request without earmarking the legislation. The nation's security should not be reduced to constituent politics.

A Free, Safe, and Prosperous Nation

Reaching the goal of keeping America free, safe, and prosperous will take a tremendous commitment by the executive branch and Congress. The President's budget remains a reliable indicator of whether the Homeland Security Department's strategic priorities are taking the country in the right direction in terms of security and the DHS mission. Congress and the President should work together to ensure that the end budget moves toward accomplishing DHS missions, strengthening and maturing the DHS enterprise, and gives American taxpayers more security for every dollar spent.

Jena Baker McNeill is Policy Analyst for Homeland Security in the Douglas and Sarah Allison Center for Foreign Policy Studies, a division of the Kathryn and Shelby Cullom Davis Institute for International Studies, at The Heritage Foundation.