Congress is currently working on reauthorizing the federal child nutrition programs, which include school meal programs. The last time Congress reauthorized these programs, it passed the controversial Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010,[1] a major priority for President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama.[2]

The Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act made a number of significant changes in the child nutrition programs. This paper focuses on two of these changes.[3]

- The increasing federal control of school meals through the nutrition standards and

- The expansion of eligibility for school meals to include many middle- and high-income households.

Instead of assuming that this flawed law should be the starting point from which to make changes, legislators should identify sound policy options and then develop legislation accordingly. This means developing meal standards that respect the role of parents and local decision-making and avoid expanding the welfare state to cover many middle-class and wealthy families.

Nutrition Standards

The primary question regarding nutrition standards is actually not about nutrition at all; rather, the question is whether the federal government should dictate a strict one-size-fits-all approach for schools participating in the meal programs or local governments and parents should make these decisions.

The Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 developed a restrictive federal approach. The standards are extremely prescriptive and provide little flexibility for schools. There are calorie limits, minutely detailed nutritional requirements, and portion size restrictions.[4] For example, students are required to take fruits and vegetables at lunch regardless of whether they want them.[5] The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) does not merely require schools to offer vegetables; it specifies that they must offer “Dark green,” “Red/Orange,” “Beans/Peas (Legumes),” “Starchy,” or “Other” vegetables.[6] Nor do these specifications stop with vegetables; the only type of milk that can be offered must be fat-free (plain or flavored) or low-fat (1 percent or less), and it must be unflavored.[7]

Township High School District 214, a suburban Chicago, Illinois, district that includes Arlington Heights and reportedly dropped out of the school lunch program, provides a good example of some of the problems associated with these standards.[8] According to a district spokesperson:

The new school lunch guidelines are too restrictive; for example, not allowing kids to buy hard-boiled eggs or certain yogurts. School officials also have noted the new guidelines consider hummus to be too high in fat, and pretzels to be too high in salt; non-fat milk containers larger than 12 ounces could not be sold either.[9]

A 2014 Government Accountability Office report surveyed state child nutrition officials regarding the school lunch program, finding significant food waste, increased costs, insufficient food storage, and the need for newer kitchen equipment.[10] The School Nutrition Association, which represents the professionals providing meals to students, has repeatedly called for greater flexibility.[11] The National School Board Association cautioned, “School boards cannot ignore the higher costs and operational issues created by the rigid mandates of the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act.”[12]

Given this centralized approach, it is not surprising that the existing standards have been a failure. The first priority for a meal program should be to ensure that children in fact have food that they will eat and that will meet their caloric needs. School meals can be even more “nutritious” if local educational authorities make these decisions with feedback from parents. Standards developed locally are the most likely to meet the unique needs and demands of students, parents, and the local communities.[13]

Regrettably, the House and Senate bills would only make minor changes to the existing standards. For example, the House bill would prohibit the more restrictive sodium reductions from going into effect, allowing a new and stricter target to be set only if based on strong scientific evidence.[14] Neither bill, however, would significantly alter the centralized approach to nutrition.

Community Eligibility Provision

A fundamental tenet of federal means-tested welfare programs is that recipients are low-income.[15] The Community Eligibility Provision (CEP), however, expands school meal benefits to students who are not low-income[16] and who very well could come from wealthy families.[17] CEP allegedly exists in part to reduce the administrative burden on schools by not requiring schools to process applications and to minimize any “stigma”[18] associated with receiving federal benefits.[19] It is ironic that proponents would claim that administrative burden is a concern when they are generally the same individuals who are pushing for the excessively burdensome nutrition standards.

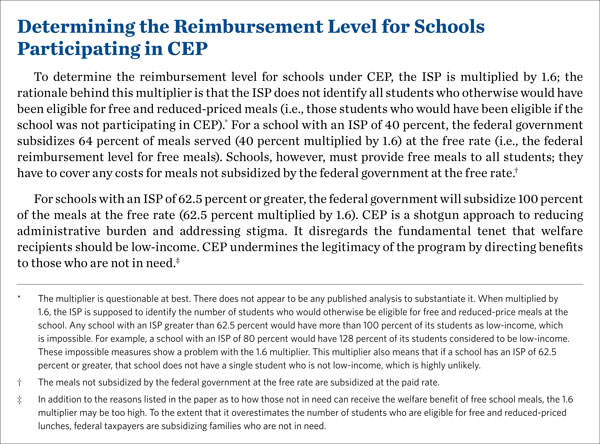

Through generous federal subsidies, CEP encourages schools to provide free meals to all students regardless of income level if certain criteria are met. If at least 40 percent of students in a school, a group of schools, or a school district are identified as eligible for free meals because they receive a benefit from another means-tested welfare program like food stamps (a measure referred to as the Identified Student Percentage or ISP),[20] then all of the students can receive free meals.

It is not just middle-class and wealthy students at schools that have an ISP of at least 40 percent who can receive free meals. Because a school’s ISP can be calculated using all schools or some schools in the district, a school with zero low-income students would be treated as having an ISP of at least 40 percent when grouped together with high-ISP schools in the district, resulting in free meals for all of its students.[21]

Even the USDA’s own research has not examined who receives the welfare benefits. In its final report evaluating CEP, the USDA found that in the schools it evaluated, student participation in school meals increased 5 percent for school lunch and 9 percent for school breakfast.[22] The USDA, however, did not measure whether the increased participation was a result of low-income students using the program or middle-class and wealthy students using the program.

The Senate bill fails to address the problems of CEP. The House bill does make a small change by increasing the ISP threshold, currently at 40 percent, to 60 percent.[23] This move would help to minimize the number of free meals being provided to students from middle-class and wealthy families.

Even with the House change, however, many of CEP’s problems would still remain, including its legitimization of the idea that free meals should be given to students who are not low-income. Since an ISP could still be based on a group of schools, not on a school-by-school basis, low-income area schools would still be able to help high-income area schools provide free meals to middle-class and wealthy students. Further, the high and questionable multiplier of 1.6 would still remain in effect.

What Should Be Done

To address the two issues identified above, Congress should:

-

Develop parent-driven nutrition standards, not bureaucrat-driven standards. School districts should be allowed wide power to develop their own nutrition standards. The federal role should be very limited,[24] focusing on making sure that children receive the minimum number of calories and setting general minimum standards, such as by requiring schools to make proteins and fruits and vegetables available (but not requiring students to take them).

School districts should implement standards that meet these general federal requirements. This system is parent-centered because parents are much more likely to have influence with their local officials than with bureaucrats in Washington, D.C. In addition, this approach allows local officials to tailor their standards to the needs of their communities and the demands of parents and students.

-

Eliminate CEP. This provision expands school meal assistance beyond its intended population. The elimination of CEP would have no impact on the eligibility of low-income students to receive free and reduced-priced meals.[25] Eliminating CEP would ensure that free meals are going only to students who are low-income. This change would reduce the number of free meals offered by schools. The purpose, however, is not to provide as many meals as possible regardless of who receives them, but rather to provide meals to students who are low-income.

CEP appears to be a backdoor approach to move toward a universal school meal program. The school meal programs, as has been long-standing policy, properly differentiate between those who are low-income and those who are not. CEP gets around this for some schools by manipulating data through artificial and unsubstantiated means to give all students free meals in those schools. Congress needs to eliminate these means of data manipulation that improperly give free meals to students of middle-class and wealthy families, including ISP thresholds, grouping schools to determine eligibility for all the schools, and the use of a multiplier.

Free lunches should go only to those students who are eligible for free lunches, and reduced-price lunches should go only to students eligible for reduced-price lunches. Other students should be eligible for neither. This obvious and common-sense point seems to have been lost. Congress should stop efforts to expand school meal programs beyond their intended low-income recipients.

Conclusion

Policymakers have the opportunity to get child nutrition policy right. Rather than tinkering with flawed policies grounded in extreme government-centered principles, lawmakers should set forth child nutrition policy that is based on sound principles of federalism, respect for parents, and responsible stewardship of taxpayer dollars.

—Rachel Sheffield is a Policy Analyst in the DeVos Center for Religion and Civil Society, of the Institute for Family, Community, and Opportunity, at The Heritage Foundation. Daren Bakst is Research Fellow in Agricultural Policy in the Thomas A. Roe Institute for Economic Policy Studies, of the Institute for Economic Freedom and Opportunity, at The Heritage Foundation.