Abstract: The Islamist insurgency in Russia’s Northern Caucasus threatens to turn the region into a haven for international terrorism and to destabilize the entire region, which is a critical hub of oil and gas pipelines located at Europe’s doorstep. Neither Russia’s excessive use of military force nor its massive economic aid to the region appear to have helped. The U.S. and its friends and allies should keep a close watch on the region. In the meantime, the U.S. should work with neighboring countries to improve their border security. The U.S. should also encourage and work with Middle Eastern countries to stop the flow of cash to the Islamist terrorist organizations.

Russia’s Northern Caucasus is turning into one of the most volatile, lawless regions in the world and a hotbed for international terrorist activity in spite of decades of Russian military operations and repeated assurances from the Russian government that peace has been achieved. As Russia continues to lose control of the region, it is becoming a significant base for Islamist terrorist organizations and organized crime and may ignite an even greater terrorist campaign inside Russia and beyond.

Islamist terrorists from the self-proclaimed Caucasus Emirate have already attacked energy infrastructure, trains, planes, theaters, and hospitals. They are increasingly involved in terrorist activities in Western Europe and Central Asia, including Afghanistan. North Caucasus Islamist insurgency is part of the global radical Islamist movement, which is deeply and implacably inimical to the West and the United States.

Russian counterinsurgency programs have partially failed, marred by excessive use of force and repeated human rights violations. The Russian civilian and military leadership tends to overemphasize counterterrorist operations, while largely ignoring the broader counterinsurgency perspective.[1]

To alleviate the hostilities, the Russian government has implemented many economic and developmental programs and provided billions of dollars in aid to the North Caucasus in the past few years. Russian officials have invested to curb the appeal of radical Islam among the youth, but the area’s overall economic and social prospects remain grim due to the ongoing security crisis caused by heavy-handed security policy and the pervasive corruption and mismanagement of the Russian government.

Thus, Russia’s entire counterinsurgency strategy is in question. Its primary goal is “to make the local population less afraid of the law enforcement than the insurgents,”[2] but the overly violent Russian approach has often produced the polar opposite. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the North Caucasus has experienced two major wars and numerous skirmishes, resulting in hundreds of thousands of casualties and internally displaced persons, while the fear of terrorism has spread throughout Russia.

Spreading ungovernability in the Northern Caucasus facilitates the emergence of Islamist safe havens, complete with terrorist training facilities, religious indoctrination centers, and hubs of organized crime. This should be a cause for concern for the United States.

The Dangers of North Caucasian Instability

The danger from North Caucasian instability is threefold.

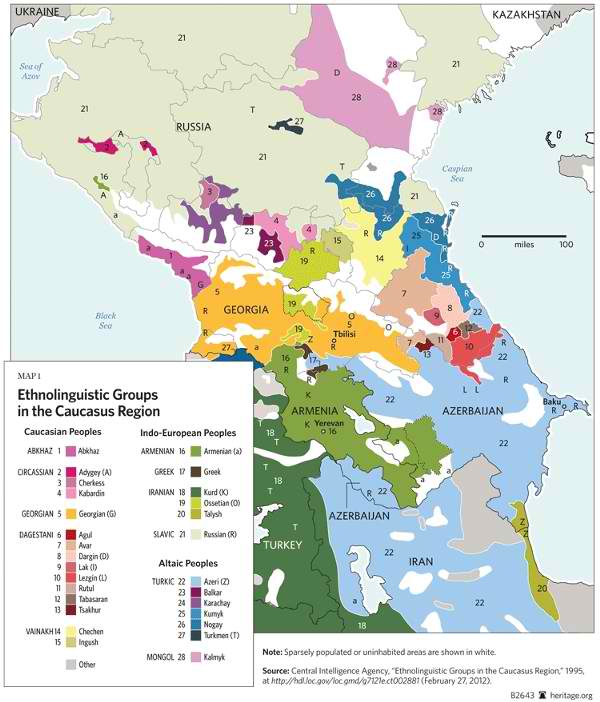

First, the presence of such an ungovernable enclave in Southeastern Europe compromises the border stability of U.S. friends and allies, such as Georgia and Azerbaijan. Unrest in the North Caucasus increases the security threats to the two countries, where border security is already problematic due to the Georgia–Russia and Azerbaijan–Armenia conflicts. Poorly guarded borders increase the risk of cross-border terrorist activities. For example, Pankisi Gorge in Georgia served as a staging area for Chechen insurgents during the Second Chechen War and provided “a vital link to the outside world which was not under the direct control of Russia.”[3] Porous borders also provide a convenient route for illegal trafficking in drugs, weapons, people, and even nuclear materials. Such activities may negatively influence America’s relations with Russia, the states of the South Caucasus, and Europe, and they could disrupt U.S. logistical support for operations in Afghanistan.

Second, the North Caucasus pose a global threat as a potential terrorist base in close proximity to U.S. European allies. Some terrorists are already operating in the European Union (EU), as the recent discovery and arrest of a Jamaat Shariat cell in the Czech Republic illustrates.[4] For now, such incidents are rare and minor, but the massive North Caucasus diaspora in Russia and Europe will likely become a growing security concern for European authorities. Due to Russian pressure on the North Caucasus insurgency,[5] local terrorist groups are too preoccupied to pose an immediate threat to the U.S. and Europe. Some experts have assessed terrorist activity in the region as a “minor global threat.”[6]

Third, destabilization in the Northern Caucasus threatens not just Russia, but also the security of the whole Caucasus, including Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The region is a principal north–south and east–west hub. Oil and gas pipelines linking the Caspian Sea to Western Europe pass through Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey. The large oil and natural gas reserves in the Caspian basin supply a significant share of Europe’s energy needs and may provide an even greater share in the near future as projects such as the Nabucco natural gas pipeline come online.[7] The importance of pipelines and their vulnerability to sabotage make them preferred targets of local insurgents.

U.S. policymakers should be concerned that the North Caucasus may devolve into an anarchic haven for Islamist terrorism and criminality. Security of America’s friends and allies, prevention of a terrorist safe haven in the ungovernable North Caucasus, and ensuring the free flow of energy resources are high priorities for the U.S. in this volatile region. Such a threat should not be allowed to develop.

The interests of the United States and its allies could suffer from Russia’s failure to respond appropriately to Islamist extremism. Washington needs to develop a strategy to respond to potential “spillover” from Islamist insurgency in the North Caucasus. The U.S. and its allies need to monitor the region for early signs of danger in order to respond appropriately. A modest investment in intelligence, diplomacy, and capacity-building with U.S. friends and allies could help to mitigate the rising Islamist threat and the effects of misguided Russian policies.

The North Caucasus’s Bloody History

Warfare between Russians and the peoples of the North Caucasus has a bloody history that stretches back more than two centuries. The Russian Empire conquered and colonized the North Caucasus in the second half of the 18th century and continued warfare there for almost 100 years. Rebellions also occurred under Soviet rule.[8] In the past decade, however, radical Islam has transformed the conflict from primarily a struggle for independence to a theater of operation in the broader global Islamist onslaught, determined to use terrorism to turn Russia’s Northern Caucasus into a Caucasus Emirate. If successful, the North Caucasus will become a bridgehead for further Islamist expansion in the region.

As a result of these wars, interethnic strife in Russia is on the rise. Many Russians contemptuously view North Caucasus Muslim ethnic groups as inferior to the rest of the Slavic, Orthodox population. At the same time, radical Islam is becoming more popular among young people, which has allowed Islamist groups to expand their educational, recruitment, and terrorist activities in the region.[9] Extremism is also spreading from the North Caucasus to the rest of Russia, creating the potential to radicalize other Muslim groups, such as the Tatars and Bashkirs. From the indigenous populations’ perspective, Islam has always been the banner of the war against the Russian Orthodox Christians and unbelieving Communists.

Islam has deep roots in the region. Arab invaders introduced Islam into the Caucasus in the 8th century. Shortly thereafter, most people in the North Caucasus had converted to Islam, while peoples to the south, including the Georgians and Armenians, remained loyal to Orthodox Christianity.[10] In the late 18th century to early 19th century while the region was under the influence of the Persian and Ottoman Empires, the Russian empire made major inroads into the region.[11] Despite fierce resistance, the Czar’s forces ultimately conquered the region in the Caucasian War, led by generals who used scorched earth tactics to achieve their goals.[12] Since the conquest, North Caucasians’ Muslim religious observance and distance from Russian authority made it easy for these peoples to maintain their distinct Islamic identity, which mostly follow Sufi orders.

North Caucasian Muslims saw the collapse of the Czarist empire and the Bolshevik revolution as an opportunity to end a century of occupation, but the Red Army mercilessly crushed them, using chemical weapons and air power. In 1944, Stalin deported hundreds of thousands of Chechen and Ingush from their North Caucasus homeland to Central Asia,[13] even though thousands of their people had died fighting the Nazis in the Red Army. Stalin feared that peoples in this region would effectively resist his plans for secular Russification. Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet leader from 1953 to 1964, allowed Chechens and Ingush to return home in 1956. Nevertheless, relocation and secularization pushed Islam to the margins of society. Additionally, in the late Soviet era the lack of educated, moderate imams led them to import extremist preachers and terrorist emissaries, who helped to introduce radical Islam to a poor and desperate population, especially to the youth.[14]

In 1991, Dzhokhar Dudayev, a former Soviet air force general, was elected the president of Chechnya. After the fall of the Soviet Union, he declared Chechnya’s independence from the newly independent Russian Federation,[15] arguing that if Soviet republics were given independence, Chechnya should also be independent. In 1994, President Yeltsin authorized the Russian military and security services to launch what was intended to be a short operation to suppress the separatist unrest. Russian Defense Minister Pavel Grachev promised Boris Yeltsin “to take Grozny with a paratroop regiment in four hours.”[16]

The ensuing hostilities were brutal. Thousands of Russian troops and insurgents died. Over 70,000 civilians died, and hundreds became internally displaced persons. The Chechen rebels eventually defeated Russian forces, which withdrew from Chechnya and signed the Khasavyurt Accord in 1996, which recognized the de facto independence of Chechnya. After the victory, the local economy collapsed, unemployment rose, and the indigenous government became ineffective. Local gangs and radical groups exploited this power vacuum to impose Sharia law in certain areas, engage in slave trade, and attack and plunder Russian villages. Criminal activity became rampant.[17] As a result, Chechnya found its new autonomy compromised by the emerging Islamist terrorist rule.[18]

The Second Chechen War

By 1999, the character of the Russian–Chechen conflict changed dramatically, with radical Sunni Islamism becoming a significant motivating factor in the Chechen insurgency. In addition, the Chechen national leadership changed from nationalist former Soviet military officers to violent Islamists. Prominent foreign figures emerged for the first time. Al-Moganned and Ibn Al Khattab, Saudi-born emissaries of al-Qaeda, further radicalized the Chechen movement.[19] Islamists viewed the North Caucasus as “infidel-occupied territories” and their struggle as defensive jihad (holy war).

In the summer of 1999, Shamil Basayev, the amir (military leader) of the Chechen Islamists, attacked neighboring Dagestan. The Second Chechen War began as Vladimir Putin became prime minister under President Yeltsin. In 2000, Russia recaptured Grozny, reestablished its control over the area, and ended Chechnya’s de facto independence.

Although the traditional Sufi Naqshbandi sect of Islam remained dominant in everyday life among senior Chechen governmental officials and throughout much of the North Caucasus, militants tend to follow the more radical Salafi sect, recently imported from the Middle East.[20] The messages of egalitarianism, struggle against corruption, and injustices inflicted by the local Chechen government made Salafism increasingly popular among the youth and those affected by war.

North Caucasian Terrorist Activities Since 1999

Despite Russia reestablishing control of Chechnya, terrorist activity in the Russian hinterland has increased significantly. According to the Global Terrorism database, Russia ranked seventh in the world in the number of suicide attacks between 1991 and 2008. The more than 1,100 terrorist attacks resulted in more than 3,100 deaths and 5,100 injuries.[21]

Basayev was the main culprit behind the major terrorist attacks in Russia between 1999 and 2006, most notably the attack in 2002 on Dubrovka Theater in Moscow and the Beslan school hostage takings and massacres in 2004. However, in both attacks, the majority of casualties were caused by poorly executed Russian government rescue operations.

Under Basayev’s leadership, the Salafi/Wahabbi ideology became stronger in the region than ever before.[22] After Russian forces neutralized Basayev in 2006, Doku Umarov, the new leader, strengthened ties with local radical Salafi Islamic communities (jamaats) and proclaimed the Caucasus Emirate (Imarat Kavkaz), a pan-Caucasus terrorist group with the objective of establishing an Islamic emirate consisting of all North Caucasus republics, including Dagestan, Ingushetia, and Kabardino-Balkaria.[23]

The U.S. government has realized the danger that Umarov poses. Since May 2011, the U.S. government has offered a $5 million reward for information leading to his capture. In June 2011, Forbes magazine listed Umarov as one of the world’s 10 most wanted fugitives.[24] On March 10, 2011, the U.N. Security Council determined that Umarov is associated with “Al-Qaeda, Usama bin Laden or the Taliban” through his ties to the Islamic Jihad Group, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, and the Riuadus-Salikhin Reconnaissance and Sabotage Battalion of Chechen Martyrs, which is responsible for many high-profile attacks in Russia.[25] The U.S. government has designated Umarov[26] and Caucasus Emirate as being involved in terrorism and supporting “terrorists, terrorist organizations or acts of terrorism.”[27]

Basayev’s attacks were mostly guerilla operations designed to target Russian civilians to pressure the Russian government to withdraw from the Northern Caucasus. This was the motivation behind the 2002 Dubrovka Theatre hostage crisis, which left 170 dead in Moscow, and the 2004 Beslan hostage crisis and massacre in North Ossetia, which left 331 people dead, including 186 children.[28]

To resist this onslaught of terrorism, the Russian military and security forces continued operations in the region. After Basayev’s death in 2006, Umarov increased the intensity and frequency of attacks on security forces, government facilities, and high-value civilian targets. These attacks include bombings of the Nevsky Express (Moscow–St. Petersburg) trains in 2007 and 2009, the Moscow Metro double suicide bombing in 2010, and the suicide bombing at Domodedovo Airport in January 2011.[29] Although Umarov is the mastermind behind most terrorist attacks in Russia, the broader Islamist terrorist movement maintains much of its strength through the many local radical Islamic jamaats. These groups have an independent capacity for terrorist activity. Therefore, eliminating Umarov will not solve the problem of Islamic terrorism. Nor would his death dramatically change the level of terrorist activity or the structure of terrorist organizations in the region.[30]

Northern Caucasus’s Ties with the Global Islamist Movement

One ominous development has been that al-Qaeda and other foreign extremist organizations in the Middle East and Central Asia have increased their financial and moral support of the radical Islamist movement in the Caucasus. The most important connections to the global terrorist movement have been through Yusuf Muhammad al’Emirati (“Moganned”), a Saudi-born al-Qaeda member who arrived in Chechnya in 1999, and Abdulla Kurd, al-Qaeda’s international coordinator of terrorist cells. Moganned was a leader of Arab and foreign fighters in the Caucasus and one of the leaders of the Chechen insurgency. Both Moganned and Kurd were killed by Russian special forces in April 2011.[31]

The Caucasus has been on al-Qaeda’s radar screen for a decade and a half. Ayman al-Zawahiri, the current leader of al-Qaeda, visited the region in the mid-1990s and was even temporarily in Russian custody.[32] Al-Zawahiri has referred to the Caucasus as one of three primary fronts in the war against the West.[33]

Recently, Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), the most active and dangerous al-Qaeda affiliate, has been expanding its global reach. For example, AQAP translated al-Qaeda’s online journal Inspire into Russian to attract extremists in the North Caucasus and other Muslim areas in Russia.[34] In addition, evidence indicates that terrorists who were trained in the North Caucasus have joined al-Qaeda and other operations in Waziristan in Pakistan.[35]

Furthermore, Doku Umarov made clear that the Caucasus is an integral part of the global jihad: “after expelling the kuffar we must reconquer all historical lands of Muslims, and these borders are beyond the boundaries of Caucasus,” and “Everyone who attacked Muslims wherever they are are our enemies, common enemies.”[36] Umarov recently reaffirmed his commitment to jihad, stating that although “many of the emirs and leaders” have been killed, “Jihad did not stop, but vice versa, it expanded and strengthened” and that “the death of the leaders of the jihad cannot stop the process of the revival of Islam.”[37]

The Kadyrov Solution

Since the First Chechen War, the Russian government has believed that the best way to resolve the security and economic problems in the North Caucasus is to subsidize the economy and to maintain a brutal police state. Sheikh Akhmad Kadyrov was the pro-Kremlin president of the Chechen Republic after the Second Chechen War. He fought for the rebels in the First Chechen War, but defected to the Russian side because of the rising influence of Wahhabism among the Chechen insurgents. He was assassinated on May 9, 2004, in Grozny by a large bomb during a parade marking the Soviet Union’s victory in World War II.[38] In 2007, Vladimir Putin appointed Ramzan Kadyrov, Akhmad’s son, the president of Chechnya. Since the start of Ramzan Kadyrov’s first term, Grozny has been rebuilt.

Despite this apparent success, Kadyrov has attracted international scrutiny. To increase his popularity among the faithful, he legalized polygamy in violation of Russian law. He also built the largest mosque in Europe, which he claims is a symbol for a peaceful Chechen Islamic identity.[39] In addition, he declared the anniversary of his father’s death as a day of national mourning and sanctioned an essay contest on the topic of Ramzan’s “heroic personality.”[40] Many have criticized these grandiose schemes, believing they represent a Kadyrov cult of personality.

During their reigns, both Akhmad and Ramzan Kadyrov used brutal, oppressive measures against both terrorist groups and the civilian population.[41] After the Second Chechen War, Akhmad and Ramzan Kadyrov integrated former rebels into their state security force, which many have accused of kidnapping and torture. A U.N. special rapporteur stated that “the government-supported forces use largely the same methods as the terrorists…terrorizing the civilian population.”[42] The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe has condemned Ramzan Kadyrov for war crimes in Chechnya,[43] and the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom has recommended imposing a visa ban on him and freezing his bank assets.[44] Although no direct evidence implicates him in war crimes, the assassinations of some of his political opponents and critics, including the 2006 killing of journalist Anna Politkovskaya and 2009 killing of human rights activist Natalya Estemirova, have raised suspicions among Russian and Western human rights advocates.[45]

In response, Kadyrov has lambasted the U.S. as an enemy of Russia and Chechnya, accusing it of supporting terrorism in the North Caucasus.[46] In fact, anti-Western rhetoric has become common in Kadyrov’s speeches, providing consistent and intentional disinformation about the conflict in the region. For example, in a September 2009 interview, he ranted:

All of it [the regional conflict] is handiwork of the West. The Muslim world doesn’t help them [the insurgents].… They are not “freedom fighters,” these are extremely well-trained terrorists. We are at war with American and British Special Forces. They fight neither against Kadyrov, nor against traditional Islam, they fight against the sovereign Russian state.[47]

Kadyrov did not invent this rhetoric. In a 2008 speech, Putin commented on the conflict in the North Caucasus, “Here we have encountered open instigation of the separatists by outside forces interested in weakening and possibly ruining Russia.”[48] While the Kremlin does not officially endorse Kadyrov’s more extreme position, it has tacitly consented to his words and actions, which are evidently derived from Putin’s official statements. Other members of the Russian leadership adopt the anti-American rhetoric more explicitly. For example, in 2004, Duma Deputy Nikolai Leonov attempted to blame the U.S. for the Russians’ assassination of Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev, a former Chechen leader and a North Caucasus Islamist ideologue[49] to avoid international criticism of the Russian government’s extrajudicial actions. Shifting the blame to the U.S. and the West has become a common tactic to rebuff international criticism of Russia’s heavy-handed tactics in the North Caucasus.

While Kadyrov and the Kremlin boast about the improving situation in Chechnya, neighboring republics, especially Dagestan, have seen an increase in terrorist activity, largely because the militants left Chechnya due to Kadyrov’s crackdown. In reaction, neighbors have responded by replicating the “Kadyrov solution,”[50] but using the Kadyrov methods in these areas seems to have fomented more hatred, unrest, and escalating violence. Dagestan President Magomedsalam Magomedov has acknowledged that the situation remains dire, with the terrorists seemingly able to replenish their numbers with ease regardless of how many the security forces kill or detain.[51] In fact, Chechnya has witnessed a reemergence of warfare between Russian forces and terrorist groups and an increasing death toll. The Chechen government has responded with increased use of intimidation tactics, such as burning down the homes of relatives of suspected rebels.[52] Such government-sponsored violence does not appear to have reduced public sympathy for the Islamists.

Economic Morass

One factor contributing to the North Caucasus insurgency is the grave local economic situation. For years, Moscow has poured billions of dollars into the republics, but much has been dissipated by rampant corruption, nepotism, and waste, and the North Caucasus economy has remained stagnant. As a result, people, especially the youth, are more willing to join terrorist organizations than ever before because Islamists pay their fighters relatively steady salaries.

Private investors have been reluctant to invest in the region because of widespread violence, poverty, bureaucratic inefficiency, and government corruption.[53] Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the Caucasian republics have received 60 percent to 80 percent of their budgets as subsidies from the federal government, creating a dependency on the federal government. Unsurprisingly, unemployment remains high, especially in the terrorist hotspots of Ingushetia (53 percent unemployment), Chechnya (42 percent), and Dagestan (17.2 percent).[54] Furthermore, many people in Russia, the Middle East, and Islamic communities around the world pay religious charitable donations (zakat). Some of these funds are ultimately funneled to terrorist hands, making zakat one of the most important sources of financial support for terrorist networks, including in the North Caucasus.[55]

To increase economic control of the region, President Dmitry Medvedev announced in early 2010 the creation of the North Caucasus Federal District (NCFD), an administrative unit that consolidates the seven republics of the Northern Caucasus. Prime Minister Putin simultaneously launched the Commission for the Socio-Economic Development of the North Caucasus Federal District to oversee government programs in the region.[56] Medvedev and Putin hope that the reorganization will successfully overhaul the regional economy and create around 400,000 jobs in the coming years. However, achieving these objectives will be difficult without addressing root causes of extremism and corruption.

Unlike many other regions in Russia, the North Caucasus region is not rich in natural resources, except oil in Chechnya, and does not have a developed industry. Alexander Khloponin, the presidential envoy to the NCFD, unveiled a long-term multilayer development plan through 2025.[57] The plan sets a near-term annual growth target of 10 percent for the NCFD. To help achieve these objectives, two of the five major government programs will try to develop the tourist industry by exploiting the region’s mountainous geography.[58] However, this goal is optimistic given that the national economy grew by only 4 percent in 2010.[59]

The 2014 Winter Olympics in nearby Sochi might cause an economic boom, but the Winter Games could also become a target of North Caucasus terrorism.[60] Given the proximity of the terrorist bases to Sochi, Russia faces security dilemmas unprecedented among past host countries.

Demographic Trends: Time Is Not on Russia’s Side

The Muslim population in the Russian North Caucasus is growing, and the regional economy is becoming less able to support the growing population. The North Caucasus Federal District is home to an estimated 9.5 million people, a 6.3 percent increase over the population in 2002. [61] The Russian Federation has an annual birth rate of 11.05 births per 1,000 citizens and a death rate of 16.04 deaths per 1,000 citizens, indicating that the population is in decline. In 2010, the NCFD had a birth rate of 17.4 and a death rate of 8.7, indicated that the population is growing rapidly.[62]

Youth compose a large portion of the growing North Caucasian population, compounding the unemployment problem. Many will likely join radical Islamic groups.[63] Data from the 2002 census suggest a profile of a person who is highly vulnerable to recruitment by radical Islamist groups: an unemployed, unmarried Muslim man in his mid to late twenties with a university education. Such a person would be at least familiar with radical Islamist philosophies and would be a prime recruiting target of Islamist terrorist groups. [64] In the North Caucasus, an alarming number of individuals fit this profile.

Time is working against Moscow. Without an effective response to radical Islam or a successful economic development program, Russia will lose the Northern Caucasus to the radicals in the long run, if not sooner. According to polling before the March 2010 Moscow subway attack, 61 percent of Russians were afraid of being a victim of terrorism. This percentage rose sharply to 82 percent and remained around this level after the Domodedovo Airport attack in January 2011.[65] In 2009 and 2010 polling, only about half of Russians thought that the government could defend them from terrorists. In 2011, only 35 percent believed that terrorism can be defeated.[66]

This general lack of faith has spurred much xenophobic and anti-Muslim sentiment in Russia. In December 2010 and January 2011, ultranationalists staged violent anti-immigration protests in Moscow’s Manezh Square, resulting in mass arrests.[67] In April 2011, hundreds more marched in Moscow to protest against the billions of dollars in subsidies that help to maintain the fragile economic situation in the southern borderlands of Russia.[68]

However, the blame is misdirected. In a 2009 Russian public opinion survey, 26 percent identified the United States as the largest terrorist threat, while 38 percent blamed the Chechen terrorists.[69] Such misguided sentiment among the Russian population could further damage the U.S.–Russia relationship. The United States has a record of cooperation with Russia in its counterterrorist efforts. While the U.S. needs to do more to make the Russians aware that America is on their side, the Russian government needs to face the reality and stop blaming the U.S. for its 200-year-old North Caucasus insurgency.

Drawbacks of the Russian Response

The most common Russian response to the insurgency in the North Caucasus is a military, counterterrorist, or law enforcement operation, which have been plagued with corruption, extra-judicial killings, and administrative detentions. Additionally, due to poor doctrine, tactics, and training, these operations are characterized by a “desire to substitute firepower for infantry,” “indiscriminant use of firepower,” and excessive violence and collateral damage.[70] The local tradition of “blood revenge” (vendetta or krovnaya mest’) magnifies the violence into a self-perpetuating cycle. As Gordon Hahn writes, “There are inevitably cases when local MVD [Ministry of Internal Affairs agents] exact revenge against mujahedeen family members not on orders from Moscow, Grozny, or Makhachkala but in accordance with this [blood feud] tradition.”[71]

Moscow’s official stance on the issue does not help. The common official designation for North Caucasian insurgents and terrorists is “bandits,”[72] which presupposes a police response, instead of counterterrorism and counterinsurgency response. This faulty designation neglects both the ethnic and religious roots of the ongoing insurgency. Moreover, it lacks any form of due process for finding and eliminating the bandits, opening the way for corruption and wanton violence against innocent civilians.

Since the late 1990s, Putin has used instability in the region as an excuse “to curtail political rights and freedoms and put pressure on the mass media.”[73] As a result, accusations of terrorism have become a tool of convenience. Russian and international human rights organizations continue to criticize Moscow’s approach. In anApril 20, 2011 joint letter to Medvedev, Human Rights Watch, and three of the largest Russian human rights organizations decried “the nearly absolute impunity for egregious human rights violations, such as abductions, enforced disappearances, torture, and extrajudicial killings—by members of the local law enforcement and security agencies.”[74]

Regional Implications of the North Caucasus Insurgency

The insurgency is affecting neighboring countries and being influenced by them.

Georgia, Azerbaijan, and the North Caucasus. Georgia and Azerbaijan share their northern borders with Russia’s North Caucasus and are therefore exposed to violence spilling across the border. For example, during the Second Chechen War, the Pankisi Gorge in Georgia served as a shelter for Chechen terrorists and a meeting place with international extremist leaders.[75] The U.S. has provided Georgian forces with counterterrorism training to address this issue. Recently, Sunni fighters from Azerbaijan are reportedly participating in the North Caucasus insurgency.[76]

At the same time, both countries are U.S. strategic partners in the region, and their central governments strongly oppose the insurgency. Georgia’s current government is resolutely pro-Western, and Azerbaijan’s secular and moderate leadership is ideologically opposed to the Sunni/Salafi extremists from the North Caucasus as well as pro-Iranian Shi’a extremists. Overall, “the Azeris and Georgians are more fearful of the Chechen rebels than they are of the Russian army.”[77] Both countries participate in NATO’s Partnership for Peace program and have contributed significantly to U.S. efforts in Iraq and Afghanistan[78]—commensurate with their size and capabilities.[79]

In recent years, President Obama’s “reset” with Russia has lowered the profile of American involvement in the region to the dismay of elites in both countries. While the Obama Administration continues to give lip service to the U.S. commitment to support the two countries’ territorial integrity and independence, it clearly prioritizes U.S. relations with Russia. In other words, the Administration is close to accepting Russia’s de facto sphere of influence in the region, while rhetorically rejecting such a scenario. The lack of U.S. cooperation and support may jeopardize the two countries’ efforts to control their northern borders, which puts them at risk to the North Caucasian extremists, who are seeking transit routes, port access, and criminal business opportunities in both countries.

The Turkey Connection. Over the past decade, Turkey’s relationship with the United States has become more problematic due to Prime Minister Erdogan’s on-again, off-again rapprochement with Iran, confrontation with Israel, and gradual Islamization of Turkish politics. The U.S. Department of State still describes the U.S.–Turkey relationship as a “friendship” because Turkey is a NATO ally, but Turkey has become much more assertive in dealing with its neighbors.[80] Turkey is also, at least in theory, a prospective EU member.

However, Turkey’s recent actions suggest that Ankara is attempting to pursue a policy of regional supremacy. Turkey has refused to open its border with Armenia, challenged Cypriot offshore natural gas exploration, and facilitated flotillas of Islamist extremists attempting to break Israel’s blockade of the Hamas-ruled Gaza Strip. The Turkish leadership supports Iranian nuclear ambitions in the bilateral and international arenas even though it is one of the countries that will lose the most to a nuclear-armed Iran. Ankara has consistently opposed or abstained on votes on U.N. sanctions designed to stop or delay the Iranian nuclear program.

Turkey’s involvement in the North Caucasus is also problematic. In the late 1990s before the Second Chechen War, Russia accused Turkey of harboring Chechen terrorists. The two countries have since come to a rapprochement, which has brought massive construction contracts, a surge in tourism, energy imports supplying 67 percent of Turkish gas and vast amounts of oil, and a lucrative nuclear reactor deal. This shift has put a stop to active Turkish support of Chechen terrorists.

In 2008, during the Russian–Georgian war, Turkey proposed a “platform for peace and stability” in the North Caucasus, a security framework that would include Turkey, Russia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia.[81] Ankara acted without first consulting Washington, Brussels, or European capitals at a time when France was engaged in negotiating a separate cease-fire between Moscow and Tbilisi. This was an obvious move by Turkey to expand its regional influence, and its outstretched hand to Russia clearly demonstrated the improved relations between the two countries. While Russia has not accepted the proposal, such an alliance, if ever formed, would minimize the U.S. presence in the region and hurt important U.S. energy and geopolitical interests.

Despite cozy relations with Russia, Turkey has a sizable and influential diaspora from the North Caucasus, which is sympathetic to the separatist and insurgent movements in the region. Russian analysts and media consistently view Turkey as hostile to Russian interests in the North Caucasus, citing financing and harboring terrorists as well as “imperialist ambitions.”[82] Recently, three men accused of involvement in the Moscow Domodedovo Airport bombing were found and shot in Istanbul,[83] suggesting that the North Caucasus terrorists may still seek shelter in the country, even if they no longer receive official support. This suggests a double standard toward terrorism when combined with Turkey’s support for Hamas terrorists and, simultaneously, a justified outcry against Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) terrorism.

Support from the Middle East. Countries in the Middle East have supported North Caucasus insurgents since the First Chechen War. The United Arab Emirates (UAE), Qatar, and the Taliban-ruled Afghanistan were the only countries to receive delegations from the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, as secessionist Chechnya was known in 1996–2000.[84] Arab countries have also given refuge to various Chechen leaders, including Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev, the second president of Ichkeria. In the late 1990s, before they were banned by the U.N. Security Council,[85] Saudi-sponsored Benevolence International Foundation and similar “charity” organizations based mainly in Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, and Kuwait contributed large sums to North Caucasian Islamists and other terrorist organizations.[86]

U.S. experts suggest that insurgents continue to receive funding from the Middle East,[87] mostly through illegal channels, but with more difficulty than in the previous decade. Still, recent reports suggest that the North Caucasus Islamists have somewhat restored the flow of money. A 2006 financial record recovered by the Russian Federal Security Service documented donations totaling $200,000 and €195,000 for 2005, which the insurgent leader considered insufficient.[88] In a 2008 interview, Vasily Panchenkov, press spokesman for the Internal Troops of the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs, suggested that the insurgents do not keep money in banks, but receive it directly from the Arab “mules” who bring it into the country,[89] thereby avoiding common tracking methods. In 2010, Russian officials recovered the insurgents’ financial records, which indicate significant contributions from foreign sponsors, including some in the UAE.[90]

Experts largely agree that there is no unified Arab policy toward Chechnya and the rest of the North Caucasus.[91] Nevertheless, the insurgents are to some degree self-financed through protection money and zakat extracted from the diaspora. In addition, ongoing financial support from the Middle East ensures that the conflict will continue. Such arrangements undermine stability in the region and U.S. interests in the Middle East and the Caucasus and in the worldwide fight against terrorism.

Failures of U.S.–EU Cooperation. It is important to distinguish between bilateral counterterrorism cooperation between the U.S. and European countries and the unwieldy, overbureaucratized EU security structures. Washington and its European allies have cooperated extensively in counterterrorism. The European Union and its member-states have a particular interest in defeating the insurgency in the North Caucasus. With its recent expansion, the EU is now closer than ever to the volatile region. Regrettably, while both the U.S. and EU have a common interest in counterterrorism and counterinsurgency efforts, current levels of cooperation are insufficient. Intelligence sharing, coordination of lists of terrorists and foreign terrorist groups, and cooperation on the extradition of wanted persons need to be expanded. Europe’s leaders at the highest level should work with NATO to launch a thorough public diplomacy effort to effectively communicate its mission and purpose in Afghanistan and elsewhere to the general public.

Former Heritage analyst Sally McNamara has noted:

The EU–U.S. counterterrorism relationship has been marked as much by confrontation as it has by cooperation. Brussels has long opposed key U.S. counterterrorist programs such as renditions, and under new powers granted by the Lisbon Treaty, the European Parliament has challenged two vital data-transfer deals—the SWIFT data-sharing agreement and the EU–U.S. Passenger Name Records (PNR) Agreement.[92]

At the same time, the Europeans blame the U.S. because, allegedly, the “US strategic debate has increasingly shifted away from counterinsurgency and stabilization operations.”[93]

With the European Union focused on dealing with Europe’s sovereign debt crisis, the U.S. should not expect Brussels to demonstrate more willingness or ability to engage positively on counterterrorism. Furthermore, the EU does not share the U.S.’s strategic approach to countering terrorism, seeing terrorism as a law and order issue, rather than a strategic and a systemic issue. Therefore, the U.S. should focus on bilateral engagement with key European nations to increase counterterrorism cooperation.[94]

What the U.S. Should Do

The U.S. and its allies are facing a growing terrorist threat from ungovernable areas around the world, and the North Caucasus is one such area. This region has a potential to devolve into an anarchic haven for Islamist terrorism and organized crime. The security of U.S. friends is at stake. The U.S. needs to work with its allies to monitor the situation to prevent the North Caucasus from becoming a terrorist safe haven and to ensure the free flow of energy resources. Specifically, the U.S. should:

- Counter the Russian blame game with targeted public diplomacy. Blaming the West to justify violent tactics in the North Caucasus has become a common tool in Russia’s information operations arsenal. The intentional spreading of targeted, officially backed disinformation—basically anti-European and anti-American propaganda—is no laughing matter, even when the conduits, such as President Kadyrov, lack credibility. Anti-American statements play a significant role in forming public opinion in Russia and neighboring countries, feeding a “growing and systemic anti-Americanism within and from Russia.”[95] These attempts should be cut at the root. The U.S. should counter Russian officials who spread baseless rumors and innuendos. The U.S. international broadcasting directed by the Broadcasting Board of Governors and State Department-directed lectures, publications, and Web presence should address and quash these allegations. To boost U.S. media presence in Russia, the State Department should pressure Russian officials to allow Voice of America and Radio Free Europe to broadcast in Russia on television and FM and AM radio. U.S. public diplomacy should also expose Russian human rights abuses in the North Caucasus, which fan the insurgency and undermine Russia’s counterinsurgency strategy. Finally, U.S. public diplomacy should counter proliferation of extremist propaganda and support moderate Muslims who wish to stand against radical Islam. The U.S. and its European allies should actively seek out and support moderate North Caucasus Muslim leaders who oppose terrorism and radical Islamic ideology.[96]

- Reinvigorate security relations with Georgia and Azerbaijan. Considering the ineffectiveness of Russia’s strategy against the North Caucasus insurgency, it is in the U.S. interest to boost friendly relations with Georgia and Azerbaijan and to assist them in combating the spillover of illegal activities from the North Caucasus. The U.S. should maintain a strong presence in the region, reinforcing the friendly ties with the two countries and extending the necessary political and military aid to their anti-terrorism efforts.

- Help Georgia and Azerbaijan to strengthen border controls. The porous borders between Russia and Georgia and Azerbaijan are major security concerns. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security should assist Georgia and Azerbaijan in making their border security effective and transparent; protecting energy sources and pipelines; and restricting passage of arms, drugs, terrorists, and related goods and information. However, U.S. assistance must not enhance repressive measures against civilian populations in violation of international law and U.S. standards.

- Cooperate with and train local intelligence and law enforcement forces. Building on the experience of training Georgian counterterrorism forces for operations in the Pankisi Gorge, the U.S. should expand anti-terrorism programs with Azerbaijan and Georgia and forge closer ties with the local counterterrorism and intelligence forces. The local intelligence services, which enjoy local knowledge, presence, and access, can provide useful and timely information to the U.S. about North Caucasus terrorist and extremist networks. The U.S. should work with Georgian and Azeri anti-terrorism and border guard forces until they can effectively secure their borders, thus minimizing direct U.S. involvement.

- Obtain Turkey’s cooperation in fighting North Caucasus terrorism. The U.S. should emphasize Turkey’s obligations as a NATO member and request Turkey to provide information on North Caucasus extremists and their supporters. Washington should remind Ankara about the massive U.S. support in fighting PKK terrorists. The U.S. should specifically request Turkey to provide all available intelligence on North Caucasus terrorist groups and their Turkey-based diaspora support networks and to cooperate with Georgia and Azerbaijan in defeating terrorist activities.

- Pressure Middle Eastern states to stop their nationals from funding and training terrorists. The U.S. needs to put significant pressure on the states—especially Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE—whose nationals are involved in funding or training insurgents in the North Caucasus to stop the flow of cash to terrorist groups, bankrupt the North Caucasian insurgency, and prevent its integration into the worldwide Islamic extremist movement. This can be pursued through private interventions at the highest levels by U.S. policymakers, including the U.S. Vice President, Secretary of State, and Director of National Intelligence. The U.S. should also use the Financial Action Task Force to disrupt terrorism funding from wealthy individuals and foundations in the Persian Gulf and charitable contributions to wage war and brainwash youth. If private diplomacy fails, the “name and shame” approach could also be effective.

- Engage European states in bilateral anti-terrorism cooperation, expand NATO-based cooperation, and continue negotiations with the EU members on counterterrorism. Considering the difficulties in dealing with the EU’s cumbersome system and the lack of immediate success in recent negotiations, the U.S. should negotiate with interested European states on further bilateral agreements on information sharing and counterterrorism. This can achieve timely cooperation in key areas and inspire other member states to act as they realize the advantages of such arrangements.[97] European countries are key allies in combating terrorism worldwide and need to be involved in developing the strategies and tactics to deal with the North Caucasus. The U.S. should continue to make clear its commitment to fighting terrorism and emphasize its common interests with the Europe.

Conclusion

The pattern of Islamist insurgency in the North Caucasus is not unique. It is a part of a global trend in which the lack of state sovereignty allows violent Islamists, organized criminals, and terrorists to control certain areas, as is seen in parts of Somalia, Yemen, North West Pakistan, Afghanistan, and southern Thailand. The North Caucasus is part of this trend.[98]

While this insurgency is also the most serious challenge to Russia’s security and sovereignty since its independence in 1991, the United States and its allies and partners have a strong interest in reducing the Islamist threat. One high priority is to keep the insurgency isolated as much as possible from the global Islamist movement. Through security and intelligence cooperation, economic and technical assistance, and public diplomacy, the U.S., its allies and partners, and Russia can meet this important regional challenge.

—Ariel Cohen, Ph.D., is Senior Research Fellow in Russian and Eurasian Studies and International Energy Policy in the Douglas and Sarah Allison Center for Foreign Policy Studies, a division of the Kathryn and Shelby Cullom Davis Institute for International Studies, at The Heritage Foundation. The author is grateful to Janos Bako, a lecturer at the Corvinus University of Budapest and a research volunteer at The Heritage Foundation, and to Robert Nicholson and Anatolij Khomenko, members of The Heritage Foundation’s Young Leaders Program, for their assistance in preparing this report.