Ten years after Heritage and NACDL researchers issued the original Without Intent report highlighting the need for Congress to provide adequate mens rea protections when creating new criminal offenses, change has been slow but steady, with gradual movement on the federal level and some movement in the states. There has been slight improvement, but more progress should be made. Despite significant political polarization, improving the criminal legal system by combating overcriminalization and ensuring strong mens rea protections are reforms that have inspired bipartisan interest and support—and can continue to do so. Overcriminalization is a widely acknowledged problem on both sides of the aisle, and there is growing awareness of the need for improvements to ensure adequate mens rea protections. Download the full report here.

Without Intent Revisited: Foreword

Slightly more than 10 years ago, scholars and researchers from The Heritage Foundation (Heritage) and the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (NACDL) embarked on an ambitious project: to catalogue and analyze the mens rea requirements—that is the intent or culpable mental state requirements—for certain new criminal measures proposed during the 109th Congress.

The title of the groundbreaking report that resulted from this effort, Without Intent: How Congress Is Eroding the Criminal Intent Requirement in Federal Law, says it all. It contained sobering findings. Of the 446 criminal offenses studied, 57 percent lacked an adequate mens rea requirement. And more troublingly, Congress enacted 23 new criminal offenses into law that lacked adequate mens rea requirements.

As we wrote in our Foreword to that report, “A core principle of the American system of justice is that individuals should not be subjected to criminal prosecution and conviction unless they intentionally engage in inherently wrongful conduct or conduct that they know to be unlawful.” We made clear that this “is not just a legal concept; it is the fundamental anchor of the criminal justice system.”

Given the importance of Congress providing adequate mens rea requirements in new criminal provisions, as well as Heritage’s and the NACDL’s findings, the report made a number of recommendations. While a lot has changed over the past decade, our organizations’ commitment to “the belief that criminal lawmaking must return to its fundamental roots by requiring true blameworthiness and providing fair notice of potential criminal liability” has not.

So Heritage and the NACDL have once again partnered to see how Congress is doing in this regard; to see which, if any, of the report’s recommendations were adopted; and to update the previous report by examining certain criminal provisions put forward in the 114th Congress. The findings of this new report, Without Intent Revisited: Assessing the Intent Requirement in Federal Criminal Law 10 Years Later, are encouraging, but show that further progress is needed.

We hope that Representatives, Senators, their staff members, and anyone else who reads this new report take its suggestions seriously. Fostering awareness of the problem of inadequate criminal intent requirements in criminal laws is the first step toward principled reform. Taking appropriate action is the next step.

The commonsense, workable solutions proposed here are such appropriate actions. If enacted, Congress will have taken significant steps toward making sure that only those who acted with the appropriate criminal culpability are found guilty and punished under criminal laws.

Edwin Meese III The Heritage Foundation

Norman L. Reimer National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers

Introduction

Harmful events occur on a daily basis and often have devastating consequences. But as a society and under the law, we draw distinctions between conduct—even the same conduct—depending on whether it occurs accidentally or intentionally. Take a car accident for example. In the event of an accident or ordinary negligence on the part of the driver who slammed into another car, criminal liability likely does not attach.REF But, if the driver intended to slam into the car, that driver is facing a different situation. Criminal liability could, and likely would, attach.REF

This is an important distinction. In the U.S. legal system, people are not typically criminally punished for accidents, but they may be criminally punished for their wrongful conduct when they acted with a “guilty mind.” In the law, this “guilty mind” requirement for criminal liability to attach is known as a mens rea requirement.

This centuries-old requirement, which separates wrongful criminal conduct from conduct that is innocent or accidental, goes back to the earliest days of Anglo–American criminal law.REF Historically, most criminal offenses were malum in se—that is, inherently evil or wrong. People easily understand that murder, arson, theft, robbery, and rape are, by their very nature, wrongful acts.

But today, many more acts than these are prohibited. In all likelihood, many citizens have committed a federal criminal offense at some point in their lives—even if they did not realize their conduct was prohibited.REF For instance, if someone attempted to save an injured woodpecker’s life, they committed a federal crime.REF If someone looked for arrowheads on federal land—even if they were unsuccessful—they committed a federal crime.REF If someone sold onion rings using diced onion without explicitly saying so, they committed a federal crime.REF If someone sold a fur coat on which the required label was not written in English, they committed a federal crime.REF The list goes on and on.REF

But these crimes and others like them are not inherently wrong. They are only crimes because the law says so. They are malum prohibita offenses—unlawful only by virtue of a statute, or worse, regulation.REF

The long-standing maxim ignorantia juris non excusat (ignorance of the law does not excuse) has generally been accepted in U.S. law, although its contours have been winnowed and stretched at various times by the Supreme Court.REF This legal maxim made some sense historically when the majority of crimes were malum in se. The presumption was that criminally prohibited conduct was “definite and knowable,” even by the average person. But with today’s voluminous criminal code, the continued validity of that presumption has repeatedly been called into question.REF

Statutory and Regulatory Crimes

It is difficult to imagine how the average person could be expected to “know” the law when no one, including our lawmakers and the U.S. Department of Justice, knows how many federal crimes are actually on the books. Despite multiple attempts throughout the past few decades, neither the federal government itself nor private entities have been able to successfully count the number of federal crimes.REF These failures suggest a problem of both overcriminalization and overfederalization of the criminal law.REF Right now, the best estimate is that there are somewhere around 4,500 statutorily created crimes.REF

Compounding the problem of the vast number of federal crimes is the fact that Congress has also delegated certain criminal lawmaking authority to federal agencies in many contexts. Again, no one knows exactly how many crimes are currently contained in the Code of Federal Regulations, where the rules created by these agencies are catalogued.REF

Much of the conduct prohibited by these regulations is not inherently wrongful. The average person is likely unaware of the vast majority of these crimes and may have no effective notice whatsoever that his or her conduct may be prohibited. Thus, ensuring that an adequate mens rea provision is included in statutes and regulations that create criminal offenses is critical.

Without Intent: The Original Report

As scholars from the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (NACDL) and The Heritage Foundation wrote just over 10 years ago:

Accordingly, one of the critical functions served by an adequate mens rea requirement is to protect those who are reasonably mistaken about or unaware of the law. As one travels along the continuum from pure malum in se conduct, such as murder, towards entirely malum prohibitum conduct, such as fishing without a permit, the fair notice provided by the conduct itself diminishes to the point of vanishing. It is an obvious injustice to punish an individual for conduct that is not inherently wrongful if she did not know, and had no reasonable prospect of knowing, that her conduct was prohibited by law. This is why the principle that finding a person criminally responsible requires a mens rea, or guilty mind, and not just an actus reas, or guilty act, is essential to a just system of criminal law. When the actus reus is one that is malum prohibitum, fair notice is diminished or eliminated, and the burden to compensate for that deficiency falls squarely upon the mens rea requirement.REF

The authors of that study promulgated this sound advice as part of a groundbreaking study to see whether, and how well, Congress was providing adequate mens rea requirements in bills its members introduced that proposed to create new criminal conduct.

This 2010 study’s title, Without Intent: How Congress Is Eroding the Criminal Intent Requirement in Federal Law (“Original Report”), tells the story. NACDL and Heritage scholars and researchers reviewed all bills proposed in the 109th Congress (2005–2006) to see which ones created criminal offenses. Because they wanted to primarily examine whether Congress was providing adequate mens rea provisions for malum prohibitum offenses—and in part, for administrative reasons—they excluded all proposed criminal offenses that involved violence, firearms, drugs and drug trafficking, pornography, or immigration violations.REF The exclusion of these offenses allowed the authors to study more complex criminal bills which often contained more vague or unclear mens rea requirements.

That left 446 new non-violent criminal offenses to examine. Of those, the study found that 57 percent lacked an adequate mens rea requirement. And, troublingly, “23 new criminal offenses that lack[ed] an adequate mens rea requirement were enacted into law.”REF

The study’s authors defined “an adequate mens rea” as follows:

[A] proper and adequate mens rea requirement should reflect the differences in culpability that result when individuals with different mental states engage in the same prohibited conduct. This point is well illustrated by the differing mens rea requirements that apply to homicide, or the killing of a human being. Even with the same bad act—a killing—different levels of mens rea define different offenses, which carry different punishments. Thus, in federal law, manslaughter is the unlawful killing of a human being “without malice” and carries a maximum sentence of 15 years in prison. Murder in the second degree requires “malice aforethought” and carries a maximum sentence of life imprisonment. Murder in the first degree requires both “malice aforethought” and that the killing be “willful, deliberate, malicious, and premeditated”; it carries a maximum sentence of death. Mens rea requirements such as these not only help to assign appropriate levels of punishment, but also to protect from unjust criminal punishment those who committed prohibited conduct accidentally or inadvertently.REF

The study’s authors went on to describe their methodology:

The authors and their researchers analyzed the non-violent criminal offenses in 203 bills (128 from the House and 75 from the Senate) introduced during the course of the 109th Congress. Because many of the bills included more than one criminal offense meeting the study’s criteria, the number of criminal offenses included in the study (446) is greater than the number of bills. Each offense’s mens rea requirement was analyzed and graded as Strong, Moderate, Weak, or None. If a mens rea requirement fell between two categories, it was assigned an intermediate grade, for example, None-to-Weak. However, in order to give the benefit of the doubt to congressional drafting, these offenses were considered as having the higher, more protective grade for the purposes of this study’s data reporting.”REF

Those offenses labeled as being in the None or Weak categories were considered to have inadequate mens rea protections.

To help Congress combat this problem of creating new criminal offenses without adequate mens rea protections, the study’s authors proposed five policy recommendations. To wit:

- Enact default rules of interpretation ensuring that guilty-mind requirements are adequate to protect against unjust conviction;

- Codify the rule of lenity, which grants defendants the benefit of the doubt when Congress fails to legislate clearly;

- Require adequate Judiciary Committee oversight of every bill proposing criminal offenses or penalties;

- Provide detailed written justification for and analysis of all new federal criminalization; and

- Redouble efforts to draft every federal criminal offense clearly and precisely.REF

Impact of the Original Report

The Original Report sparked bipartisan interest in the problems of overcriminalization, weak intent requirements, and criminal justice reform more broadly.REF In the wake of the report’s publication, the House Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism, and Homeland Security held a hearing, “Reining in Overcriminalization: Assessing the Problem, Proposing Solutions,” led by Representatives Bobby Scott (D–VA) and Louie Gohmert (R–TX).REF

At the hearings, Representative Scott called Without Intent a “remarkable bipartisan study” that “raise[d] important questions about the proper role of the Federal criminal code” and documented the problems of “vagueness in criminal law standards and the disturbing disappearance of the common law requirement of mens rea.”REF Several witnesses testified that the recommendations proposed by the report would strengthen Congress’s criminal lawmaking.REF

The cross-ideological drive to address overcriminalization persisted for some time. A few years after the publication of the Original Report, the House Judiciary Committee unanimously created the Over-Criminalization Task Force of 2013 to conduct hearings and study the problem of overcriminalization. The convening and work of the task force were praised by groups across the political spectrum, including the NACDL, The Heritage Foundation, the American Civil Liberties Union, and Human Rights Watch.REF The Task Force was led by Crime Subcommittee Chair Jim Sensenbrenner (R–WI) and Ranking Member Bobby Scott (D—VA). It conducted numerous congressional hearings during its life span. In addition, Democratic members of the Task Force released a report expressing their views on the work of the Task Force and potential reform solutions.REF The Task Force and its Members expressed interest in continuing their discussions and bipartisan work on this problem.

A New Study: Assessing Overcriminalization 10 Years On

Building on this foundation, the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers and The Heritage Foundation embarked on this new study—approximately 10 years later—to assess how Congress is doing and to determine whether the recommendations in the Original Report were put into practice, and, if so, whether they were successful in improving the strength of the mens rea requirements in malum prohibita offenses.

While Congress has made some strides towards enacting stronger mens rea provisions, it still has not enacted default rules of interpretation, has not codified the rule of lenity, has not provided written, detailed justification for and analysis of all new federal criminalization, and in many cases, has still not been drafting new criminal offenses with the desired clarity.

The House of Representatives did adopt one of the recommendations from the Original Report and modified its rules to require Judiciary Committee jurisdiction over bills pertaining to “criminal law enforcement and criminalization.”REF This change became effective on January 6, 2015, at the commencement of the 114th Congress. The change was noted by then-Judiciary Committee Chairman Bob Goodlatte (R–VA), who explained that the rules change clarified the “Committee’s jurisdiction over criminal matters by adding one word, ‘criminalization,’ to our existing jurisdiction over criminal law.”REF He went on to say, “By making this change, the Judiciary Committee will have a new jurisdictional interest only in those relatively rare instances that a bill criminalizes new conduct by amending a statute that is attached to a criminal penalty without amending the penalty itself. In this instance, the Judiciary Committee will look to work with the other committees on ensuring that the new conduct is worthy of criminalization.”REF

Intent and Hypotheses. The purpose of this study is to analyze the mens rea requirements in the criminal provisions of bills introduced in the 114th U.S. Congress in order to determine whether congressional consideration of mens rea requirements has changed since the original publication over 10 years ago of Without Intent: How Congress Is Eroding the Criminal Intent Requirement in Federal Law.

Additionally, this study reviews the recommendations in the Original Report, determines whether and to what extent they were adopted, and, to the extent they were adopted in full or in part, analyzes whether they were useful in strengthening the mens rea requirements in federal criminal lawmaking. This study also reviews and reiterates several proposals from the Original Report that Congress has not yet adopted. Additionally, we make some new policy recommendations based on the findings in this new study.

The Original Report was clear in its hypothesis that review, debate, and oversight by each chamber’s Judiciary Committee would improve the clarity and strength of mens rea provisions in federal bills with criminal provisions or penalties. One of that report’s chief recommendations was that any bill with a criminal provision should be concurrently or sequentially referred to the judiciary committee of the bill’s respective chamber.

This report renews the study of that question, but also analyzes other characteristics of bills with criminal provisions. It analyzes whether the strength of the mens rea provision has any impact on, or is impacted by, a variety of conditions and outcomes, such as whether a bill passes a chamber or becomes a law.

Methodology. The study’s quantitative analysis began with a carefully considered search of Congress.gov’s database of all bills considered during the 114th Congress. The terms that composed the final search were:

- Imprison,*

- Punish,*

- Fine,*

- Guilty,

- Felony,

- Misdemeanor,

- Criminal penalty, and

- Criminal penalties.REF

Any bill that contained any of these terms was reviewed by the study team. Additionally, bills included in the policy area category of “Crime and Law Enforcement” as determined by the Congress.gov website were also analyzed. Other terms were considered but were ultimately not included in the final search because of insufficient success in finding additional bills with criminal provisions.

Ultimately, 1,348 bills were introduced in the House or Senate during the 114th Congress within the parameters of these search terms. Each of these bills was then reviewed and analyzed by the study team to determine whether it contained a new criminal provision or a change to the mens rea of an existing criminal provision.

In order to conform with the methodology of the Original Report and to ensure a like-for-like comparative analysis, this study also deliberately excluded analysis of federal criminal provisions regarding firearms, possession or trafficking of drugs or pornography, immigration violations, or intentional violence. Of course, many bills do contain criminal provisions on these subjects, and some of those were enacted into law.REF

Of the 1,348 bills analyzed, we found 226 with provisions that contained new federal criminal laws that fell within the study’s scope. We then meticulously analyzed these provisions and assigned each provision an individual mens rea grade.REF The number of bills is slightly less than the number of provisions studied because some bills contain multiple distinct criminal provisions. When those provisions had different mens rea requirements, we analyzed and graded these provisions separately. Additionally, if a bill contained minor changes to an already existing criminal provision in federal law, we did not review or count that provision unless the bill language would have changed the mens rea requirement of the existing law.

This study considers a mens rea requirement to be adequate if it is more likely than not to prevent the government from punishing a person who did not have a sufficiently culpable mental state to justify such punishment: in other words, if it provides protection from punishment when a person did not know that his or her conduct was unlawful, did not intend to violate a law, and did not engage in conduct that was sufficiently wrongful to have been put on notice of possible criminal liability.

As used in this report, the term “unlawful” means prohibited by any law, whether that law is criminal, civil, or administrative (although we are specifically focused on criminal laws and laws that contain criminal penalties). This is consistent with the usage in the Original Report.REF The analysis does not assume that for criminal punishment to be imposed a person must know that he or she violated a law that carries a criminal penalty.

The analysis and grading were based on the requirements set forth in the actual language of the offense and were guided by Supreme Court and other federal court decisions that provide statements defining or interpreting the mens rea terminology most commonly used in federal criminal statutes. When assessing each offense, the study did not adopt the perspective of how a hypothetical prosecutor would (or would not) charge the offense and did not consider whether prosecutorial discretion might protect potential defendants from unjust prosecution or conviction.

Instead, the grading and analysis acknowledges that prosecutors sometimes use their discretion to avoid unjust results and that courts sometimes read mens rea requirements into statutes in order to separate non-criminal conduct from criminal conduct. Similarly, the study did not consider how a court would rule on a motion to dismiss or motion for acquittal or whether a court would apply a limiting construction to an offense (for example, by a certain jury instruction or by invocation of the common law rule of lenity) to the benefit of a particular defendant.

Grading Methodology

This section describes the methodology the study authors used to assign mens rea grades to the bills we analyzed. Each offense was analyzed and graded based on the strength of its mens rea requirement. Each offense received one of the following grades: None, Weak, Moderate, or Strong. If the mens rea requirement for an offense fell between two categories, it was assigned an intermediate grade, such as Weak-to-Moderate. This practice followed the approach of the Original Report.

None. Offenses graded as “None” have no stated mens rea requirement at all. These may be, but are not necessarily, strict liability crimes.REF In some instances, a mens rea requirement may be implied by the other requirements of the offense language. Additionally, Supreme Court precedent is clear that only certain types of crimes pass constitutional muster if they are strict liability offenses.REF Nonetheless, any offense with no stated mens rea requirement is graded as None regardless of how a court or jury may ultimately interpret that offense language.

Weak. “Weak” offenses have at least some mens rea protection, but that protection is scant. Still, they provide at least some protection, unlike strict liability crimes. Mental states more commonly seen in civil tort claims, such as negligence or recklessness, are graded as Weak. Additionally, other mens rea requirements may fall into this category if their protections provide little defense to a person whose conduct was unintentional and who would not have actual knowledge of the facts constituting the offense.

Moderate. Offenses graded as “Moderate” provide significantly more protection. They generally require actual knowledge of the facts constituting an offense and must be more likely than not to protect a person from prosecution for inadvertent conduct. It should protect a person who did not act with sufficiently culpable mental state for all elements of a given criminal offense. Generally, the common and relatively protective mens rea requirement of “knowingly” is graded as Moderate. However, a Moderate grade indicates that the mens rea protections are not as protective as the next category.

Strong. The grade of “Strong” indicates an offense in which actual knowledge of the criminal nature of the offense element is required or the inclusion of a requirement of a specific intent to engage in clearly wrongful conduct. To the extent that a mens rea of “willfully” includes knowledge that the underlying conduct is criminally prohibited, that mens rea was typically considered Strong. Types of specific intents include a direct intent to violate a law as well as intent to do harm. A strong mens rea should protect a person who acted deliberately but who did not have knowledge that his or her conduct was wrongful or prohibited.

Data Analysis, Calculations, Findings

This section contains examples of offenses that fit within each grading criteria based on bill language and content.

None. Of the 226 offenses analyzed, 17 House bills and 18 Senate bills included potentially strict liability crimes with no mens rea protection at all. This is a concerning number of crimes that would potentially punish people who were unaware that what they were doing was wrongful.

For instance, The Drone Operator Safety Act, S. 2249, introduced by Senator Sheldon Whitehouse (D–RI), contains a potentially strict liability provision that would make it a crime for “[a]ny person [to] operate[] an unmanned aircraft in a manner that interferes with, or disrupts the operation of, an aircraft carrying 1 or more occupants operating in the special aircraft jurisdiction of the United States.”REF The offense is punishable by a fine and up to one year in prison.

While this is clearly a well-intentioned bill designed to ensure aircraft safety, its lack of any explicit mens rea protection could have harsh consequences. Even someone who diligently researched nearby airports and flight paths and who did not intend for her drone operation to come anywhere near any aircraft could be prosecuted if—even through no fault of the drone operator—an airplane diverted from its normal path and came near the drone. Some level of mens rea protection in the bill would protect a person who was careful and meant no harm.

Weak. In the Senate, eight of the 97 offenses were graded as Weak, with another 21 falling into the Weak-to-Moderate grading category. In the House, 12 of 129 offenses had a Weak mens rea. Additionally, one was graded as None-to-Weak, while 18 were graded as Weak-to-Moderate.

As an example, the Duty to Report Sexual Assault Act of 2016, H.R. 5865, introduced by Representative Patrick Meehan (R–PA), includes the following criminal provision:

(a) Whoever, being the owner or employee of a massage establishment— (1)(A) knows or reasonably suspects that another employee of the massage establishment sexually assaulted another person on the premises of, or while performing services on behalf of, the massage establishment; and (B) fails to report to such knowledge or reasonable suspicion to the appropriate law enforcement agency… shall be punished as provided in subsection (b). (b) The punishment for an offense— (1) under subsection (a)(1), is a fine in an amount not more than $1,500, imprisonment for a period of not more than six months, or both; and (2) under subsection (a)(2), is a fine in an amount not more than $500.REF

Once again, this is assuredly a well-intentioned bill. Nevertheless, the stated mens rea standard, which allows for prosecution if a person “knows or reasonably suspects” a sexual assault on the premises provides only weak protection. Setting aside criticisms of statutes that contain reporting requirements with criminal penalties,REF the mens rea of “knows” is generally reasonably strong.

However, “reasonably suspects” is a very weak mens rea standard. It leaves a person’s conduct up to the subjective second-guessing of a prosecutor, jury, or judge. Moreover, an accusation of sexual assault is a serious and weighty accusation to make. This bill would have the legal system second-guess whether someone’s conduct in not reporting was “reasonable.” This is unfair to potential defendants. Therefore, the mens rea protection in this bill must be considered weak.

Moderate. In the Senate, 40 percent of bills, 39 out of 97, were graded as Moderate. Twenty-one bills out of 97 were Weak-to-Moderate, while nine were Moderate-to-Strong. On the House side, roughly half of all House offenses we analyzed were graded as Moderate, 65 bills out of 129. As noted above, an additional 18 were Weak-to-Moderate; eleven were Moderate-to-Strong.

The Stingray Privacy Act of 2015, H.R. 3871, introduced by Representative Jason Chaffetz (R–UT), criminalizes use of a stringray or cell site simulator except pursuant to a warrant or as authorized under the Foreign Intelligence Service Act. The specific language is:

(a) Prohibition of use.—Except as provided in subsection (d), anyone who knowingly uses a cell-site simulator shall be punished as provided in subsection (b). (b) Penalty.—The punishment for an offense under subsection (a) is a fine under this title or imprisonment for not more than 10 years, or both. (c) Prohibition of use as evidence.—No information acquired through the use of a cell-site simulator in violation of subsection (a), and no evidence derived therefrom, may be received in evidence in any trial, hearing, or other proceeding in or before any court, grand jury, department, officer, agency, regulatory body, legislative committee, or other authority of the United States, a State, or a political subdivision thereof. (d) Exceptions.—Subsection (a) does not apply to the following: (1) WARRANT.—Use of a cell-site simulator by a governmental entity under a warrant issued…by a court of competent jurisdiction…. (2) FOREIGN INTELLIGENCE SURVEILLANCE…. (3) EMERGENCY….REF

This bill, with its “knowingly” mens rea is a straightforward Moderate grade. It could be stronger by using the stronger mens rea of “willfully” or by adding a specific intent requirement. However, the “knowingly” intent requirement is still quite strong and, especially with such a specific act requirement, should protect against any inadvertent conduct being prosecuted.

Strong. Of the Senate bills we analyzed, just two had a Strong mens rea protection, while another five (out of 97 total) were Moderate-to-Strong. While 11 House offenses out of 126 were in the Moderate-to-Strong category, five were considered to be Strong.

An example of a Strong mens rea requirement may be found in the Data Security and Breach Notification Act of 2015, S. 177, introduced by Senator Bill Nelson (D–FL), which contains a criminal provision stating:

Any person who, having knowledge of a breach of security and of the fact that notification of the breach of security is required under the Data Security and Breach Notification Act of 2015, intentionally and willfully conceals the fact of the breach of security, shall, in the event that the breach of security results in economic harm to any individual in the amount of $1,000 or more, be fined under this title, imprisoned for not more than 5 years, or both.REF

While this criminal provision has multiple act requirements as well as multiple mens rea standards, it provides strong protection overall. The first requirement is that a person have knowledge of a breach of security and the fact that notification of the breach is required under the Act. A person with no such knowledge should not be able to be prosecuted under the Act.

Even if the prosecution proves this element, it must then also prove a second requirement: that the defendant “intentionally and willfully” concealed the fact of the data breach. On its own, “willfully” (or “purposely”) is the strongest traditional mens rea requirement. Additionally, this clause provides a fine illustration of the interaction of the act requirement and the intent requirement. The act requirement for this clause is that the person conceal a breach. This is a significantly stronger act requirement than sometimes seen in other bills, which might criminalize failure to report or failure to provide notice. Here, those are not sufficient. The defendant must actually act to conceal the breach and must do so intentionally and willfully. This makes for a Strong intent requirement.

Other Examples

A number of offenses contain some type of criminal intent requirement, but not one that falls into the traditional categories identified in the Model Penal Code.REF These vary in level of protectiveness and range widely from easily understandable to somewhat more opaque. Some of these non-standard provisions are discussed and analyzed below.

Internet Poker Freedom Act. For instance, the Internet Poker Freedom Act of 2015, H.R. 2888, introduced by Representative Joe Barton (R–TX) sets forth a licensing regime for purveyors of online poker websites. Among other things, it states that it is “unlawful for a person to operate an Internet poker facility without a license in good standing issued to such person by a qualified regulatory authority under this title.”REF It goes on to say that “[a]ny person who violates this section shall be fined under title 18, United States Code, imprisoned for not more than 5 years, or both.”REF

In analyzing this provision, it is clear that it has no stated mens rea requirement. On its face, this could be a strict liability crime, which is a serious deficiency. However, in actuality, it would be nearly impossible to perform the actus reus this bill criminalizes without some level of intent. For example, one could not operate an Internet poker facility without doing so at least knowingly, and likely willfully intending to do so.

But someone could more conceivably operate such a facility (website) without knowing a license was required, particularly if the licensing requirement was introduced after the website had already begun operating. Nevertheless, the lack of a stated mens rea requirement leaves determinations such as these open to the interpretation of judges or juries rather than being prescribed by Congress. Additionally, there is no guarantee that these implied intent requirements will be applied to each statutory element of the crime.

Wildfire Airspace Protection Act. The Wildfire Airspace Protection Act of 2015, H.R. 3025, introduced by Representative Paul Cook (R–CA) states that, except for firefighters or other public safety officials, any person who “knowingly launches a drone in a place near a wildfire that threatens the real or personal property of the United States, or of any department or agency thereof, and is reckless as to whether that drone will interfere with fighting the fire, if the drone does interfere with that firefighting, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than 5 years, or both.”REF

This is a unique provision because it contains two distinct mens rea requirements: knowingly, for launching a drone, and recklessly, as to whether the drone will interfere with firefighting. The mens rea of “recklessly” is quite weak and would not likely protect people with no ill intent. It could also impinge or deter legitimate journalistic or scientific work. Having two separate mens rea requirements for different parts of the same offense is unusual. However, this bill, with its two distinct mens rea requirements for separate elements, at least clearly contemplates and states its mens rea requirements, which is laudable and should provide sufficient public notice.

ROBOCOP Act. The Repeated Objectionable Bothering of Consumers on Phones (ROBOCOP) Act, H.R. 4932, introduced by Representative Jackie Speier (D–CA), contains the following criminal provision:

(i) Intentional interference with call-Blocking technology.— (1) IN GENERAL.—It shall be unlawful for any person within the United States, or any person outside the United States if the recipient is within the United States, with the intent to cause harm, to take any action that causes the technology offered under subsection (d)(4)(A)(ii)(II) to— (A) incorrectly identify telephone calls as originating or probably originating from an automatic telephone dialing system or using or probably using an artificial or prerecorded voice; or (B) prevent (as such term is used in subsection (d)(4)) the called party from receiving a call— (i) made by a public safety entity, including public safety answering points as defined in section 222(h), emergency operations centers, or law enforcement agencies; or (ii) to which the called party has provided prior express consent.REF

This provision lacks a standard mens rea requirement but does contain the mental state requirement of “intent to cause harm.” This certainly provides some protection and “intentional” conduct is generally interpreted to mean at least “knowing” or often “willful” conduct, in terms of the standard mens rea categories. Nevertheless, there may be some risk that a judge or jury could interpret even reckless conduct as including an “intent to harm.” While this intent requirement is not necessarily weak, it could be significantly strengthened by including a standard mens rea requirement, such as “knowingly” or “purposely” in addition to the intent-to-cause-harm requirement.

Military Retaliation Prevention Act. The Military Retaliation Prevention Act, S. 2870, introduced by Senator Claire McCaskill (D–MO), contains the following provision:

§ 933a. Art. 133a. Retaliation (a) In general.—Any person subject to this chapter who, with the intent to retaliate against any person for reporting or planning to report a criminal offense, or making or planning to make a protected communication, or with the intent to discourage any person from reporting a criminal offense or making a protected communication— (1) wrongfully takes or threatens to take an adverse personnel action against any person; or (2) wrongfully withholds or threatens to withhold a favorable personnel action with respect to any person; shall be punished as a court-martial may direct.REF

This does not contain a traditional criminal intent requirement, but it does contain a mens rea of “intent to retaliate against any person for reporting or planning to report a criminal offense, or making or planning to make a protected communication, or with the intent to discourage any person from reporting a criminal offense or making a protected communication.”REF

This is somewhat elaborate and may be confusing. It includes two separate intent requirements: “intent to retaliate” and “intent to discourage.” It raises the thorny issue of whether someone may be subject to criminal penalties if her action had a certain effect, but that effect was not the person’s intent. For example, a person may feel that she was retaliated against because a certain personnel action was taken against, or withheld from, her. But retaliation may not have been the intent of the person taking or withholding the action. The subjective feelings of a purported victim may be relevant in some circumstances. But it is crucial that criminal liability be dependent on the actions and intent of the defendant, not on another person.

Additionally, applying criminal penalties to retaliation in an employment context, which is traditionally handled through civil law, opens up a variety of intent-related problems. Employment decisions may often be taken for a number of reasons.REF For example, if a person has an adverse employment action taken against them for a legitimate reason, but that person also has reported an incident such that they are protected from retaliation, the intent of the decisionmaker could be difficult to discern. Additionally, it is not clear if retaliation needs to be the sole reason, a major reason, or any part of the reason for an employment action being taken or not taken.REF It could be dangerous to base individual criminal liability on such thorny interpretations and determinations of intent.

Refuge from Cruel Trapping Act. The Refuge from Cruel Trapping Act, S. 1081, introduced by Senator Cory Booker (D–NJ), subjects a person to criminal penalties “who possesses or uses a body-gripping trap.”REF (The term “body-gripping trap” is defined elsewhere in the bill.) There is no stated mens rea requirement, leaving open the possibility that a person could technically “possess” an offending trap without knowing they were doing so, say, if they were driving another person’s vehicle and the offending trap was in the trunk. While case law on the meaning of “possession” or “constructive possession” may or may not be helpful, the need for this type of interpretive work could be avoided by adding a “knowingly” (or “willfully”) mens rea requirement to this statute.

An additional issue with these types of non-standard mens rea requirements is that courts are less used to seeing and interpreting them, leading to possible errors in interpretation, as well as possible issues with jury instructions. There is also consequently less guiding case law from appellate courts or other district courts.

Statistical Findings and Quantitative Analysis

This section provides a detailed explanation of the statistical breakdown for the findings of the 2021 Without Intent data (“2021 Report”).REF The mens rea grades are compared to the original 2010 Without Intent report’s conclusions.

Although the mens rea language used in most bills is standard, many bills did not use widely seen standards or uniform language. A lack of consistent terminology leads to some subjective consideration in the mens rea grading of offenses.

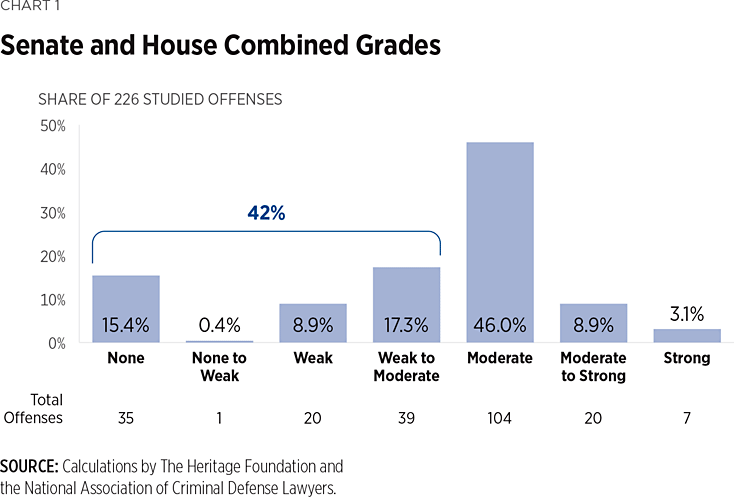

Total Bills. The 114th Congress proposed 226 non-violent criminal offenses and enacted 12 of them into law.REF These 12 enacted provisions were contained within 9 bills.REF The 226 criminal provisions were broken down into seven grading categories as can be seen in Chart 1 below. Chart 1 separates the 226 criminal provisions into the seven mens rea categories by total amount and percentage. The grading categorization used the same scale from the 2010 Original Report. However, we acknowledge that there is some level of unavoidable subjectivity inherent to assigning grades to legislative bills, even though many use standardized or close-to-standardized language.

The 2021 Report followed the same premise of the Original Report, that any provisions graded as Moderate or higher (Moderate-to-Strong and Strong) are considered adequate. Any grades below Moderate (None, None-to-Weak, Weak, and Weak-to-Moderate) are considered to have inadequate criminal intent requirements.

Of the 226 offenses studied, 42 percent (95 provisions) were considered to have an inadequate mens rea requirement because they fell below the Moderate grading threshold. In the Original Report, 57 percent (255 provisions)REF were ranked below Moderate.

On its face, this is a welcome decrease in the percentage of criminal provisions considered by Congress that had an inadequate intent requirement. Both the Moderate and Strong grades saw an increase in their share compared to the Original Report. In fact, by combining the Moderate, Moderate-to-Strong, and Strong grades together, the categories made up more than half (58 percent) of the bills. Overall, there are higher mens rea gradings in the 2021 Report compared to the Original Report.

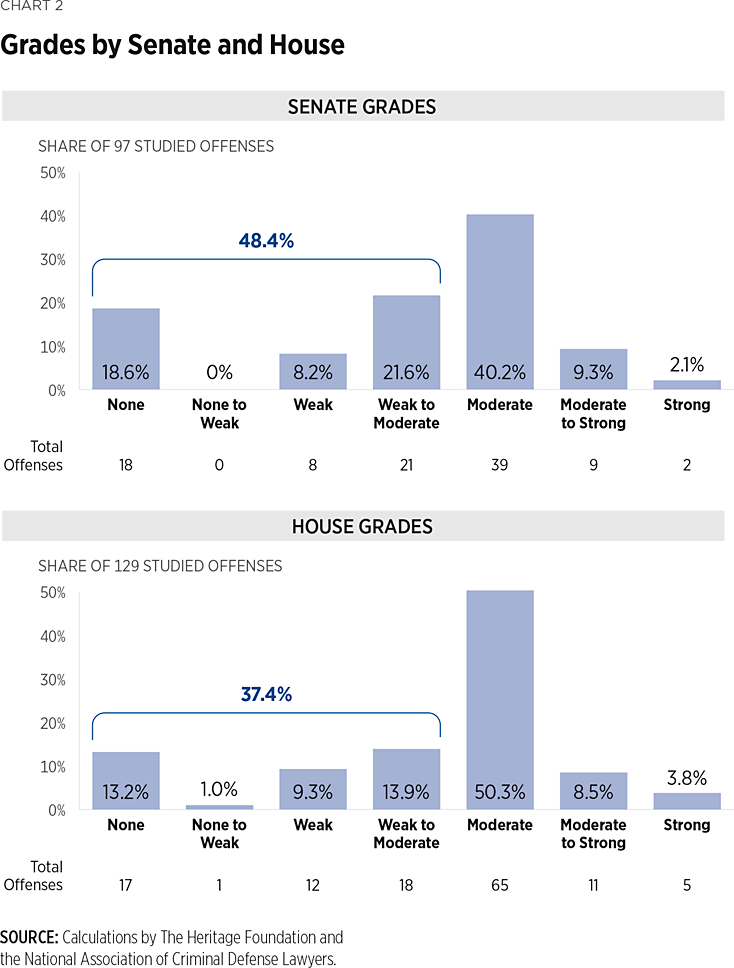

Comparing the House of Representatives and the Senate. Like the Original Report, the data was also broken down by each chamber. This data is displayed in Chart 2 below.

As previously noted, the Moderate grading category indicates a bill that meets an adequately strong level of protectiveness against unjust criminal punishment. For the 114th Congress, the House had a full 50 percent (65 provisions) of offenses meet the Moderate threshold. In the Original Report, only 30 percent of offenses in House bills were graded as Moderate. While this is a promising statistic, we caution that there is not enough data to definitively say that this finding is statistically significant.REF

The Senate’s number of provisions graded as Moderate were basically even between the two studies. In the Original Report, 42 percent of Senate provisions had a Moderate grade, while 40 percent did in the 2021 Report. The House’s improvement is laudable but is likely due to a variety of causes.

Both Moderate-to-Strong and Strong grades are considered above an intermediate level of protectiveness and are very likely to protect against inadvertent or unknowing conduct. The House had 13 percent of its provisions meet this preferred threshold. The Senate was roughly the same with 11 percent graded at least Moderate-to-Strong or better. Both of these numbers are very slightly improved from the Original Report, in which both chambers had 8 percent of their provisions in the Moderate-to-Strong and Strong threshold.REF

Despite the overall improvement in the strength of the mens rea protections in criminal provisions, at least on the House side, many bills in both chambers contained inadequate mens rea protections. Ninety-five of the 226 provisions (47 in the Senate and 48 in the House) fell below the threshold of a Moderate grade. Grades below Moderate indicate an inadequate intent requirement. Over one-third of House provisions (37 percent) fell below the Moderate grade. On the Senate side, nearly half of the criminal offenses introduced (48 percent) had a less than adequate criminal intent requirement.

Impact of Referral to the Judiciary Committee. Since the 19th century, the House and Senate Judiciary Committees have maintained a role in shaping the American criminal justice and judicial systems.REF As the Original Report rightly said, each chamber’s judiciary committee has “special expertise in crafting criminal offenses, knowledge of the priorities and resources of federal law enforcement, and express jurisdiction over criminal law.”REF

Given the knowledge and expertise of the judiciary committees in drafting bills containing criminal offenses, the Original Report hypothesized that bills that went through a judiciary committee, either exclusively or in addition to one or more other committees, would have stronger mens rea protections than those that did not.REF Ultimately, the Original Report found that bills reviewed by the Judiciary Committee of either chamber did indeed have stronger criminal intent requirements than those that did not.REF This effect was not strong, but it was statistically significant.REF

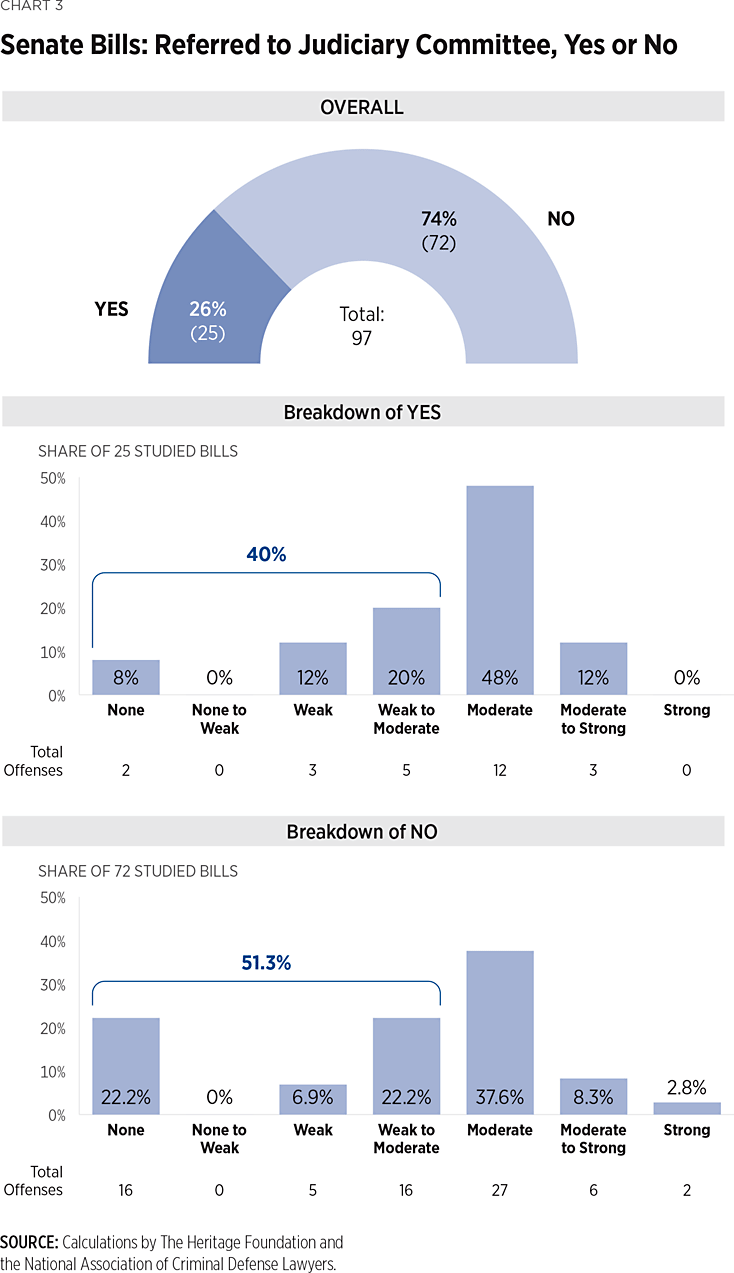

Chart 3 shows the number and percentage of Senate bills examined by this report (2021 Report) that were referred to the Senate Judiciary Committee, as well as the mens rea grades of the provisions in those Senate bills.REF

First, it is worth noting that only about one-quarter (26 percent) of Senate bills containing criminal provisions were reviewed by the Judiciary Committee. The vast majority of Senate bills with criminal offenses were not reviewed by the Judiciary Committee.REF

In analyzing the grades assigned to offenses in Senate bills, there appears to be a strong correlation between review by the Judiciary Committee and the mens rea protections of those offenses. For Senate bills reviewed by the Judiciary Committee, 15 out of the 25, or 60 percent, had adequate mens rea protection. Bills that were not reviewed by the Senate Judiciary Committee only contained adequate intent requirements 49 percent of the time.REF

Additionally, review by the Senate Judiciary Committee may have an effect on whether or not a bill contains a potential strict liability offense. Only two of the 25 Senate bills reviewed by the Judiciary Committee included a potential strict liability offense (a None grade). For bills that did not go through the Judiciary Committee, however, 16 out of 72, or 22 percent, were potential strict liability crimes that contained no explicit intent requirement at all. Because strict liability crimes are the harshest type of crime insofar as no criminal intent is required, this difference is crucial. And while we cannot say that Judiciary Committee referral is causing the improved mens rea requirements,REF it is an encouraging correlation that is worth studying further—and likely worth implementing more broadly.

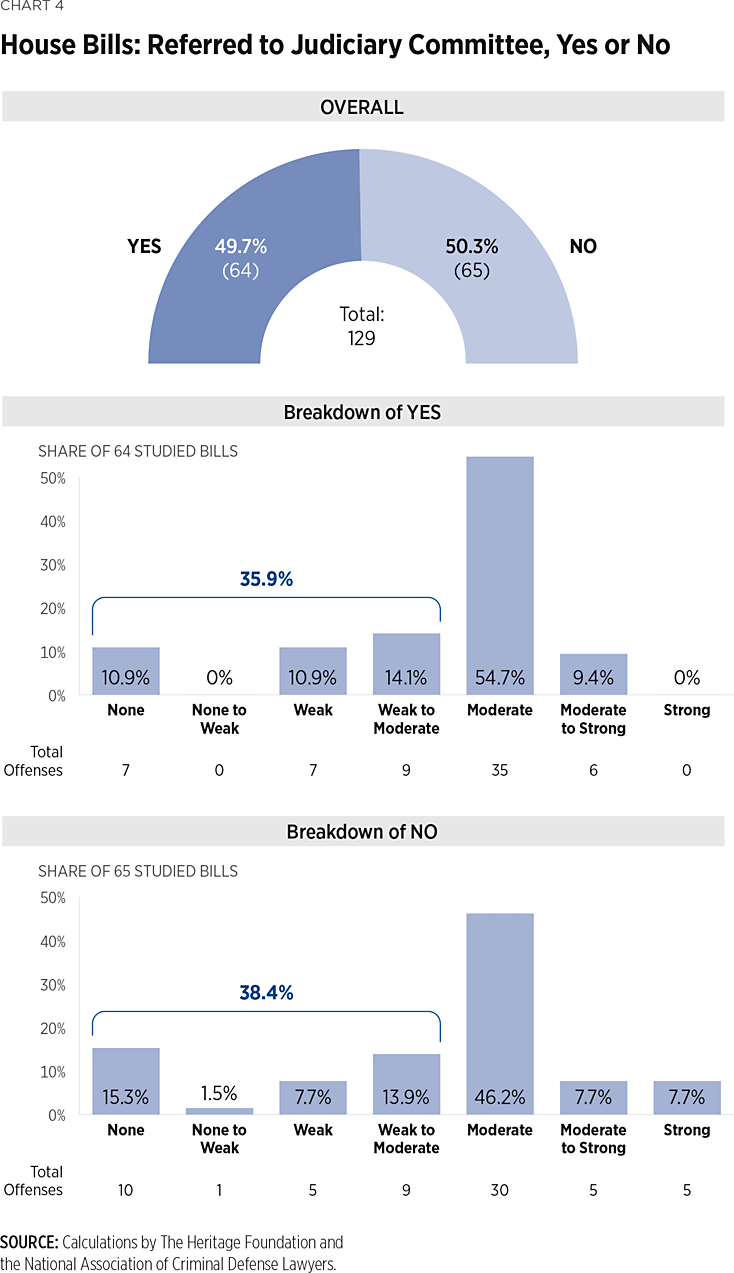

Since the publication of the Original Report, the House adopted the recommendation of changing its rules to help ensure that any bill with a criminal provision has jurisdiction in the Judiciary Committee.REF This rule was enacted in January 2015 and should have been in effect for the House bills and provisions analyzed in this report.REF

Chart 5 shows the grading analysis for bills in the U.S. House of Representatives, again broken down by whether or not the bills were referred to the Judiciary Committee, as well as the mens rea grades of the provisions in those House bills.

Initially, it is immediately clear that far more criminal bills before the House go through the Judiciary Committee than those on the Senate side. It is reasonable to assume that this is because of the effect of the House Rule X clarification of the House Judiciary Committee’s jurisdiction. Sixty-four of the 129 bills with criminal provisions in the House were referred to the Judiciary Committee, one shy of a majority of all criminal bills. Again, this is in comparison with only about one-quarter of Senate bills being referred to its Judiciary Committee.

For House bills, however, there is less of a difference in mens rea strength between bills that were referred to the Judiciary Committee and bills that were not. For bills referred to the Judiciary Committee, 41 out of 64, or 64 percent, were graded as adequately protective, indicating a grade of at least Moderate. The numbers for bills not referred to the Judiciary Committee were quite similar, however. Forty of those 65, or 61 percent, had at least a Moderate grade. Unlike the Senate bills, there was not a major difference in the number of potential strict liability crimes for bills referred to the House Judiciary Committee compared to those bills that were not referred.

Interestingly, all five of the House bills that contained criminal provisions graded as Strong were not sent to the Judiciary Committee. With a relatively small data set, there are probably not too many conclusions to be drawn from this, but suffice it to say that it is, of course, possible for legislators and their staff to draft strong mens rea protections even if those bills do not ultimately go through the Judiciary Committee.

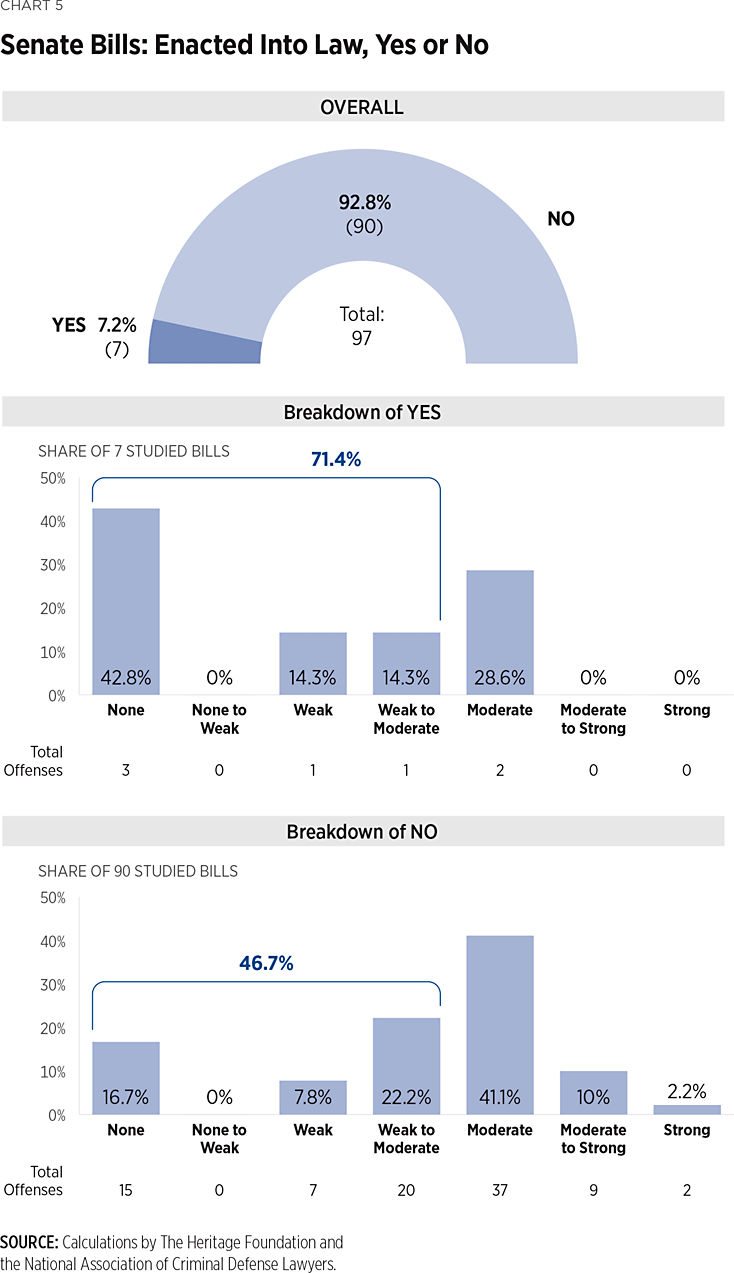

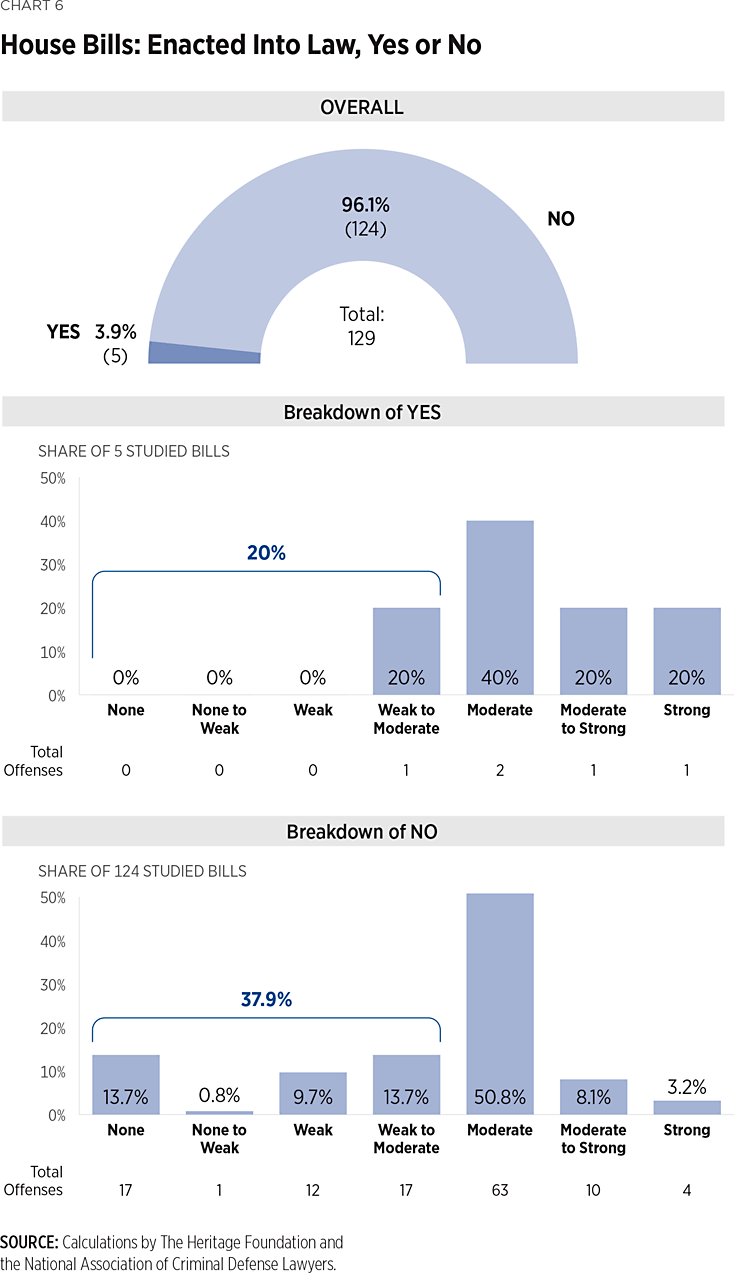

Proposed vs. Enacted. Of the 226 criminal provisions proposed by both the House and Senate during the 2014–2015 Congress that were studied in the 2021 Report, only 12 (seven that originated in the Senate and five that originated in the House) were in bills that were ultimately enacted into law.REF (See Charts 5 and 6.)

With so few criminal provisions enacted into law, it is difficult to draw any conclusions from the individual 12 that were enacted. However, within the 12 provisions, the mens rea grades are spread out quite evenly from each end of the grading scale, None to Strong.

Ideally, we would see bills with stronger provisions as being more likely to pass. The broad range of grades for the 12 enacted bills indicates that more protective measures should be adopted by both the House and the Senate. In particular, it is extremely concerning that three bills with provisions graded as None—having essentially no mens rea requirement at all—were passed by the Senate.

These are new criminal laws that could send unwary persons to federal prison despite having no idea that what they were doing was against the law and without any intent to engage in the prohibited conduct. The bills graded as Weak or Weak-to-Moderate that passed the Senate and House, which provide only weak protection, are also concerning.

Recommendations

So, where do we go from here? And more importantly, what should Congress do?

As a first step, Congress should certainly implement the recommendations from the 2010 Without Intent report. And to help members take a step in that direction, the authors have set forth a few new recommendations.

Congress Should Prioritize Clear Drafting of New Criminal Laws and Use Standard Mens Rea Provisions. We renew our recommendation from the Original Report that Congress should take care to ensure that every criminal offense is clearly and precisely drafted. This is surely a laudable goal in any context, but it is particularly important for criminal offenses. We acknowledge, of course, that Members of Congress and their staffs already strive for clarity and precision in legislative drafting. We offer the following principles to help guide this process, specifically for drafting criminal statutes.

First, all new criminal provisions should use standardized mens rea terminology, absent special justifications. “Federal law does not include standard, well-defined mens rea terms, such as those included in state criminal codes based on the American Law Institute’s Model Penal Code (MPC). The use of mens rea terms in federal criminal law can be haphazard, and almost all of the terms used to specify intent requirements have been subjected to a wide variety of (sometimes inconsistent) judicial interpretations,”REF which, as others have noted, “can make a huge difference in close cases.”REF

In a somewhat broad and simplified way, there are essentially four mens rea standards currently used in federal criminal law (though others have categorized them slightly differently):

- Willfully. This is the most protective standard. It requires that persons act with conscious intent to cause specified results, and, usually, that the persons knew their conduct was unlawful. “Purposely” is used by the Model Penal Code and has roughly the same definition, but does not generally require that the person was aware that their conduct was unlawful. Federal laws sometimes also use “intentionally” in this same way.

- Knowingly. This standard provides somewhat less protection. Depending on the court’s interpretation of the term, this requires either that the accused was aware of what he was doing or that he was practically certain that his conduct would cause a certain result.

- Recklessly. This standard is significantly less protective and does not even require intentional conduct. It requires that the accused know of a substantial and unjustifiable risk that may result from his or her conduct, but that the person consciously disregards that risk and undertakes the conduct anyway.

- Negligently. This requires that the person should have been aware of a substantial or unjustifiable risk that the material element could result from the person’s conduct. This is even less protective than the “recklessly” standard as it does not even require that the person was actually aware of the risk.REF

When Congress supplies a mens rea, it is not always clear as to which elements of the crime it applies, and it is not always clear that Congress is using the same term in the same way across—or even within—all statutes. Congress should take steps to fix this problem and standardize, to the extent possible, the mens rea terms it supplies.

As a practical matter, there are other steps Members of Congress should take to ensure clarity in their drafting of criminal provisions.

- Legislators should ensure that the drafting of bills with criminal provisions makes clear the elements to which the mens rea requirement applies.

- Legislators should clearly define any terms used in a bill that creates a new crime.

- Additionally, they should draft specific intent requirements, such as an explicit requirement of an intent to defraud or an intent to harm.

- Finally, Congress should make a clear statement in the law itself when it intends for a crime to be a strict liability offense, rather than leaving it to the courts to make this determination.

Refer New Crimes to the Judiciary Committees. Both houses of Congress should also make it a priority to require Judiciary Committee oversight for any bills creating new criminal offenses. While we cannot say for sure that referral to the Judiciary Committee strengthens the mens rea requirements of bills, it makes sense that Judiciary Committee review would strengthen the intent requirements of criminal provisions. One advantage of the committee structure used by Congress is that it allows a Committee’s Members and their staffs to gain expertise in particular areas, helping ensure consistency in important policy areas.

If all bills creating new criminal provisions are referred to the Judiciary Committees, their Members and the Members’ staffs will be aware of the need for strong mens rea provisions and the common issues that arise when drafting new criminal offenses. It would also help enact several of our other recommendations, such as using standardized mens rea terminology, ensuring that legislators make clear the elements to which the desired mens rea applies, and ensuring that a clear statement is made in the statute when Congress wishes to enact a strict liability crime.

Criminal offenses should be reviewed and considered by Members and staff who are experts in criminal law. In Congress, those experts serve on their respective Judiciary Committees. While there is, of course, a degree of jurisdictional overlap, one would not expect to see a transportation bill taken up solely by the Foreign Relations Committee or a Veterans’ Affairs bill considered solely by the Natural Resources Committee.

In general, committees do and should oversee bills that relate to their stated jurisdiction and resultant expertise. In this vein, the committee that is experienced and specializes in criminal matters should be asked to consider any bill containing a criminal offense. Even bills that also have jurisdiction in other committees should be referred to the Judiciary Committee if they have criminal provisions.

We commend the House of Representatives for adopting this rule, which was recommended in the Original Report. We urge the Senate to do so as well. However, we note that only about half of House bills with criminal provisions that we studied actually were referred to the Judiciary Committee.REF While this was a higher number than the Senate, where the Judiciary Committee only reviewed roughly one-quarter of bills with criminal provisions,REF there are still many bills that are not referred to the Judiciary Committee at all. We urge the Senate to adopt a rule requiring Judiciary Committee referral for all bills containing criminal provisions, and we urge the House to consider procedures to ensure that bills with criminal provisions are actually referred to the Judiciary Committee as House Rule X, describing committee jurisdiction, now requires.

Consider Including Defenses, Safe Harbors, or Opportunities to Cure for Certain Offenses. Congress should consider including defenses, safe harbors, or opportunities to cure in legislation in which the rules are unclear, harm is not intended, or a person might in good faith be uncertain about whether a certain type of conduct is lawful or not. This is particularly important when the underlying offense is a malum prohibitum offense and not something that is widely understood to be wrongful or widely known to be illegal.

A small number of the bills reviewed for this study did contain safe harbor or opportunity-to-cure provisions. For example, the Safeguard Tribal Objects of Patrimony Act of 2016, S. 3127,REF introduced by Senator Martin Heinrich (D–NM), criminalizes transporting or exporting certain “Native American cultural object[s].” However, the bill provides a safe harbor if the person “voluntarily repatriates to the appropriate Indian tribe or Native Hawaiian organization by not later than 2 years after the date of enactment of this section.” The House companion bill, H.R. 5854,REF introduced by then-Representative Ben Ray Lujan (D–NM), contains a similar provision.

Another example is the Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation (WIIN) Act, S. 612,REF which was introduced by Senator John Cornyn (R–TX) and which became law in December of 2016. Among the bill’s many provisions was a criminal prohibition on a person who had a financial interest in a matter before the Denali Commission from serving as a member of that Commission.REF

This provision contained a safe harbor for a person who makes immediate disclosure of the financial interest; fully discloses it; and, prior to the proceeding, “receives a written determination by the designated agency ethics official for the Commission that the interest is not so substantial as to be likely to affect the integrity of the services that the Commission may expect from the member.” We laud these efforts to provide safe harbors from criminal liability, particularly in situations in which the conduct at hand may be remedied by the defendant and when no wrongful or harmful act is intended.

Another recommended option is including only a civil penalty for a first violation, with criminal penalties being imposed only on a second, subsequent violation. This, too, is a positive step that helps to protect parties who may have run afoul of the law without any ill intent. Both the Senate and House versions of the Refuge from Cruel Trapping Act, S. 1081,REF introduced by Senator Cory Booker, and H.R. 2016,REF introduced by Representative Nita Lowey (D–NY), criminalize the possession or use of certain body-gripping animal traps, but both contain only civil penalties for a first violation. Subsequent violations may then be punished with criminal penalties. Again, this helps to protect a person who was unaware of the law and who did not act with bad intent.

Congress should consider the inclusion of safe harbors, opportunities to cure, and civil penalties for first violations in its criminal lawmaking where appropriate.

Enact a Default Mens Rea Provision. One of the best steps Congress can take is to enact a default mens rea requirement—a standard mens rea that would apply across all federal criminal laws unless Congress specifies a different one in the text of a statute. This proposal would not disrupt existing criminal laws that have any stated mens rea requirement. Instead, it would add a mens rea to existing laws that inadvertently did not include one; crimes that are currently on the books as potentially strict liability offenses, even though it may be unclear that is what Congress intended. Existing crimes where Congress explicitly and clearly called for a strict liability offense would not be changed.

On this front, there has been some progress, but unfortunately, not enough.

The initial good news is that after The Heritage Foundation and NACDL published the original Without Intent report, two Members of Congress proposed legislation that would have enacted a default mens rea requirement across all federal criminal statutes.REF Unfortunately, neither bill passed. Senator Orrin Hatch (R–UT) introduced the Mens Rea Reform Act of 2015, S. 2298,REF and Representative James Sensenbrenner introduced the Criminal Code Improvement Act of 2015 (H.R. 4002).REF

Each bill proposed a default mens rea requirement—a mens rea provision that would apply across all federal criminal laws—but they approached the task differently. Representative Sensenbrenner’s bill proposed:

If no state of mind is required by law for a Federal criminal offense— 1. The state of mind the Government must prove is knowing; and 2. If the offense consists of conduct that a reasonable person in the same or similar circumstances would not know, or would not have reason to believe, was unlawful, the Government must prove that the defendant knew, or had reason to believe, the conduct was unlawful.

While proposing a default mens rea is a step in the right direction, the specific approach of this bill did raise some questions, specifically about how some of the provisions of this bill would work in practice.REF Even with these questions, though, it received a favorable recommendation, and the Members of the House Committee on the Judiciary voted it out of committee. It never received a vote on the House floor, however.REF

Hatch’s proposed bill took a slightly different approach. The Congressional Research Service succinctly explained it like this:

S. 2298 appears to contemplate the following procedure: first, a reviewing court may be called upon to assess whether one of the exceptions in subsection (d) applies. If so, the other provisions of the bill’s mens rea framework would not appear to apply. If none of the exceptions in subsection (d) applies, the court would likely move on to subsection (c). If the covered offense contains a mens rea element, the court is instructed to apply it to each element of the offense, unless a contrary purpose plainly appears (for example, if the element is jurisdictional). If the statute does not have a mens rea element, the court would likely move on to subsection (b) and apply the mens rea of “willfully” to each element of the offense.REF

Senator Hatch’s bill also took into account existing Supreme Court precedent and other statutory provisions that might have impacted the mens rea determination.

Unfortunately, while the bill received a hearing, it never made it out of the Judiciary CommitteeREF because some Senators worried that it could be used to undermine federal health and environmental regulations that protect against corporate abuses.REF But this argument falls short. Violations of these regulations could be redressed using civil or administrative penalties. This would remedy the problem and compensate victims without the need to pursue criminal penalties. It would also avoid punishing individuals who did not intend to do anything wrong with criminal penalties and the related consequences of a criminal prosecution (and, possibly, conviction).

Those who opposed the bill also expressed some concern that the default mens rea would make it more difficult to prosecute high-ranking corporate officials for white collar and environmental crimes.REF However, enforcement of these crimes is far more likely to be directed at lower-level employees involved in the day-to-day and on-site operations of such facilities than on CEOs and other corporate leaders. The NACDL has collected extensive anecdotal evidence of people impacted by overcriminalization.REF Even a brief perusal of these stories shows that it is very often ordinary people, not corporate executives, being harmed by improvident criminal lawmaking.

While Congress has not yet been able to pass a default mens rea law, the Trump Administration took a step in the right direction and issued an Executive Order on Protecting Americans from Overcriminalization Through Regulatory Reform on January 18, 2021.REF This executive order required that when executive agencies promulgate new rules creating criminal conduct or penalties, these rules have to be specific about what conduct is prohibited and must clearly state what mens rea will apply.

The executive order also said that strict liability crimes—crimes for which the government does not have to prove any state of mind, only that a certain act occurred—are generally disfavored. The order added that in circumstances in which strict liability applies, administrative or civil remedies should be pursued rather than criminal penalties, unless there are other compelling circumstances or evidence of wrongful intent.

If an agency wanted to promulgate regulations that create new strict liability crimes, the agency had to “submit a brief justification for the use of a strict liability standard as well as a source of legal authority for the imposition of such a standard” to the Administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. Finally, the order encouraged prosecutors and agencies to only pursue criminal penalties against those who “know what is prohibited or required by the regulation and choose not to comply.”REF

Unfortunately, the Biden Administration revoked this executive order, along with several others, a few months after it was issued.REF Nevertheless, Congress should adhere to these same guiding principles in its statutory criminal lawmaking and should enact legislation to ensure it when appropriate. To begin, it could ensure that when Congress chooses to enact a new criminal law with no mens rea, it should make its intentions clear by stating so explicitly.

Thankfully, Congress has not given up and Senator Mike Lee (R–UT) introduced a default mens rea provision on March 11, 2021.REF Of course, whether this bill fares any better than previous efforts remains to be seen.

Count the Number of Crimes. This leads us to another action Congress should take: It should require a comprehensive audit and evaluation of the entire federal criminal code to determine how many crimes there are. This is an important step in identifying unneeded or redundant criminal provisions, as well as those that have an inadequate mens rea requirement.REF

Representative Chip Roy (R–TX) introduced the Count the Crimes to Cut Act of 2020 on June 18, 2020. This bill would have required the Attorney General to provide a list of all crimes in the U.S. Code within one year.REF The bill also would have required the Attorney General to list the elements of each crime, the potential applicable penalties, and the mens rea requirement for each crime. Agency heads would also be required to provide a similar list of all regulatory crimes that the agency enforces. Unfortunately, the bill never made it out of committee. We urge Congress to reconsider this or a similar measure.

However, there has been some success in reducing the number of unneeded federal crimes on the books. The Clean Up the Code Act of 2019, sponsored by Representatives Steve Chabot (R–OH) and Hank Johnson (D–GA), was introduced on January 11, 2019.REF The bill would repeal specific crimes in the federal code that were textbook examples of overcriminalization, including criminal prohibitions on misuse of the character Smokey Bear, misuse of the 4-H emblem, and the transportation of water hyacinths.REF The bill had bipartisan support and passed the House under suspension of the rules less than two weeks later.REF The bill became law in the twilight of the 116th Congress when it was included in the Consolidated Appropriations Act.REF This law is a small, but important step, in rolling back federal overcriminalization as well as an example to follow for bipartisan supporters of future efforts.

Conclusion

Ten years after Heritage Foundation and National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers researchers issued the original Without Intent report highlighting the need for Congress to provide adequate mens rea protections when creating new criminal offenses, change has been slow but steady, with gradual movement on the federal level and some movement in the states.REF There has been some slight improvement—though none that we found was statistically significant—but more progress needs to be made.

Despite significant political polarization, improving the criminal legal system by combating overcriminalization and ensuring strong mens rea protections are reforms that have inspired bipartisan interest and support and can continue to do so. Overcriminalization is a widely acknowledged problem on both sides of the aisle, and there is growing awareness of the need for improvements to ensure adequate mens rea protections as well.

Once again, we urge legislators to seriously consider and to adopt the recommendations made here, as well as those in the Original Report. If Congress must make new criminal laws, it should prioritize clear drafting of new criminal provisions and use standardized mens rea terminology consistently across those new statutes. Each chamber of Congress should refer statutes that create new crimes to its respective judiciary committee, where those committees should consider the appropriate mens rea, providing for defenses, and opportunities to cure in appropriate circumstances. Similarly, Congress should consider enacting default mens rea legislation. Finally, Congress should require that the number of federal crimes currently on the books be counted.

As the Original Report concluded over 10 years ago:

Coupled with increased public awareness and scrutiny of the criminal offenses Congress enacts, these reforms would strengthen the protections against unjust conviction and prevent the dangerous proliferation of federal criminal law. With their most basic liberties at stake, Americans are entitled to expect no less.REF

Appendix 1: Statistical Analysis of the Relationship Between the Strength of Mens Rea Provisions and Congressional Actions

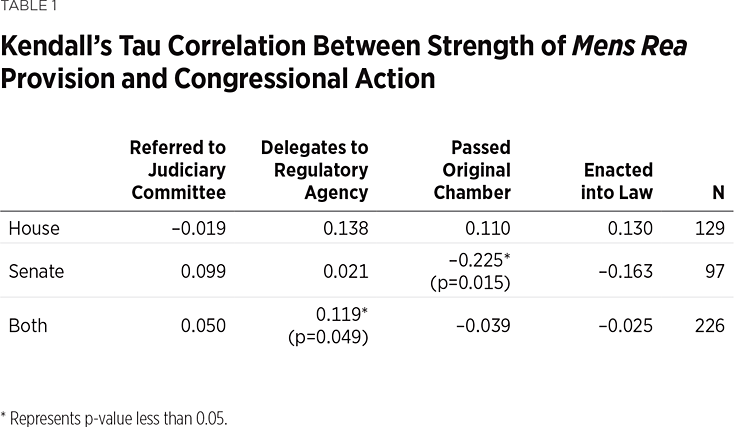

Kendall’s tau is a statistic intended to measure the direction and strength between two variables. A Kendall’s tau estimate of –1 represents a strong, perfectly negative relationship between the two variables, while an estimate of 1 represents a strong, perfectly positive relationship. Values close to zero, or those that are not statistically significantly different from zero, represent no relationship.

Table 1 presents the findings of Kendall’s Tau correlation analysis of the relationship between the strength of mens rea requirements and the specified congressional actions. For criminal offenses introduced in the United States Senate, the strength of the mens rea requirement has a negative statistically significant relationship when it is passed by the original chamber (estimate –0.225, p-value 0.015). Additionally, when the House and Senate are considered together, the strength of the mens rea requirement has a slightly positive, statistically significant relationship when it is delegated to the appropriate regulatory agency (estimate 0.119, p-value 0.049).

However, upon instituting Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons, the critical threshold for statistical significance reduces to 0.05/12=0.0041, eliminating all statistical significance altogether, thus suggesting there is no meaningful relationship between the strength of mens rea provisions and congressional actions.

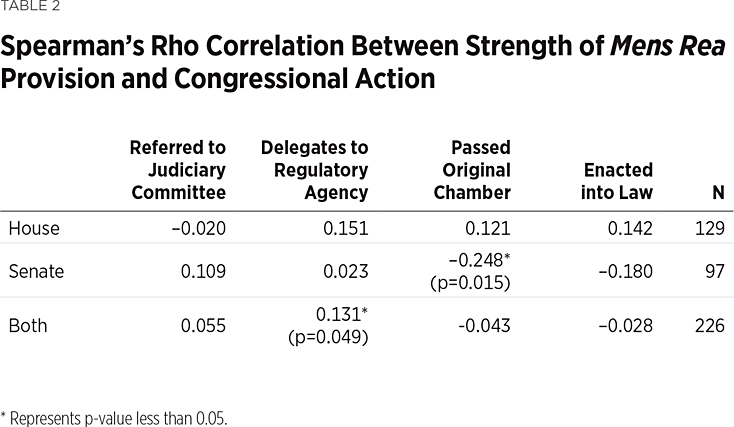

Like Kendall’s Tau, Spearman’s Rho is also a statistic intended to measure the direction and strength between two variables. A Spearman’s Rho estimate of –1 represents a strong, perfectly negative relationship between the two variables, while an estimate of 1 represents a strong, perfectly positive relationship. Values close to zero, or those that are not statistically significantly different from zero, represent no relationship.

Table 2 presents the findings of Spearman’s Rho correlation analysis of the relationship between the strength of mens rea requirements and the specified congressional actions. For criminal offenses introduced in the United States Senate, the strength of the mens rea requirement has a weak, negative relationship when it is passed by the original chamber (–0.248, p-value 0.015). Furthermore, as we saw with the Kendall’s tau analysis, when the House and Senate are considered together, the strength of the mens rea requirement has a slightly statistically significant and positive relationship when it is delegated to the appropriate regulatory agency (0.131, p-value 0.049).

Once again, however, upon instituting Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons, the critical threshold for statistical significance reduces to 0.05/12=0.0041, eliminating all statistical significance altogether, thus also suggesting there is no meaningful relationship between the strength of mens rea provisions and congressional actions.

Download the full report here.

Contributors

Foreword by Edwin Meese III and Norman L. Reimer

Kevin Roberts, PhD, President, The Heritage Foundation, Washington, DC

John G. Malcolm, Vice President, Institute for Constitutional Government, Director of the Meese Center for Legal & Judicial Studies and Senior Legal Fellow, The Heritage Foundation, Washington, DC

Zack Smith, Legal Fellow, Meese Center, The Heritage Foundation, Washington, DC

Martín Antonio Sabelli, President, National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, San Francisco, CA

Lisa Monet Wayne, Executive Director, National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, Washington, DC

Kyle O’Dowd, Associate Executive Director for Policy, National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, Washington, DC

Nathan Pysno, Director of Economic Crime & Procedural Justice, National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, Washington, DC

Kevin Dayaratna, PhD, is Principal Statistician, Data Scientist, and Research Fellow in the Center for Data Analysis, of the Institute for Economic Freedom, at The Heritage Foundation.

Acknowledgments

This study and report are the results of a collaborative project between the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (NACDL) and The Heritage Foundation. The authors would like to thank the Board of Trustees of The Heritage Foundation and the Board of Directors of NACDL, as well as President Martín Sabelli and the officers of NACDL, for their support.

Many individuals provided guidance and oversight for this project, particularly Kyle O’Dowd, Associate Executive Director for Policy at NACDL; Norman L. Reimer, Senior Consultant and immediate past Executive Director of NACDL; and John Malcolm, Vice President, Institute for Constitutional Government, Director of the Meese Center for Legal & Judicial Studies and Senior Legal Fellow at The Heritage Foundation.

The NACDL and The Heritage Foundation wish to thank GianCarlo Canaparo, Lucas Drill, Lauren McCarthy, and Shuli Carroll for their valuable efforts and insightful analysis. They also wish to thank Skadden LLP for helpful research contributions.

Kevin Dayaratna, Principal Statistician, Data Scientist, and Research Fellow at The Heritage Foundation, worked efficiently to develop and conduct the statistical analyses and conclusions supporting some of this study’s findings.