The federal estate tax (often referred to as the death tax) is a tax on a person’s lifetime accumulated property. In 2014, the death tax applies a 40 percent tax to all accumulated wealth above $5.34 million.[1] While the death tax applies to relatively few Americans and raises only tiny amounts of revenue for the federal government, it imposes substantial costs on the American economy in terms of lost jobs and reduced growth rates. It can be—and has been—devastating to family businesses and the communities in which they operate.

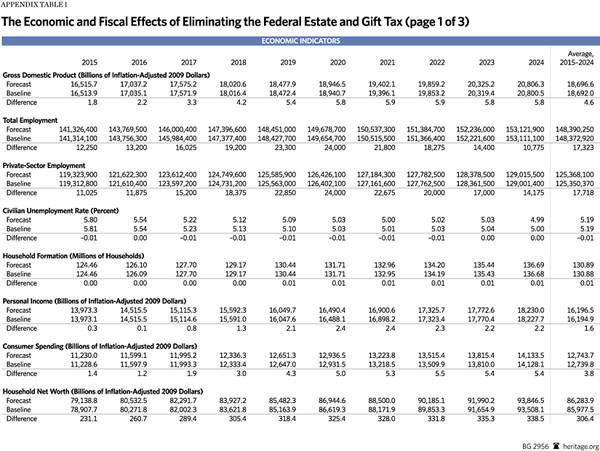

The Heritage Foundation estimates that eliminating the federal estate tax (and related gift taxes) would boost U.S. economic growth by more than $46 billion over the next 10 years and generate an average of 18,000 private-sector jobs annually. Eliminating the federal death tax would create economic opportunities for American families and free up financial assets for private-sector investment and income growth.

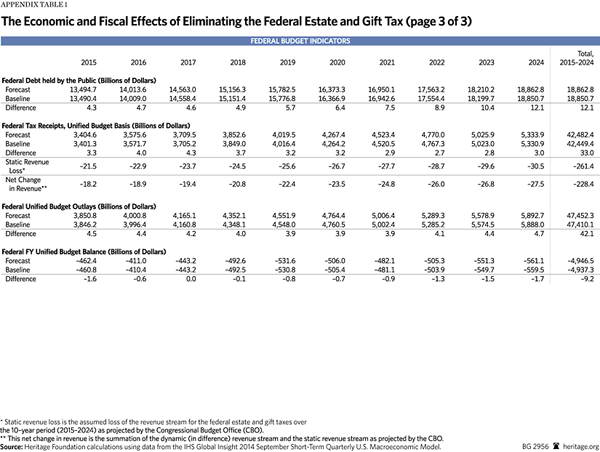

It is time to eliminate the death tax. Not only would the economy reap significant gains, but the resulting loss in federal tax revenues would be significantly lower than supporters of the death tax fear it would be. A macroeconomic simulation of estate-tax repeal estimates that the resulting job growth and increased economic activity would generate offsetting revenue, and that the total remaining reduction in tax receipts would amount to only 0.5 percent of federal revenue.

The Death Tax Kills Many Family Businesses

One of the worst features of the death tax is the effect it has on U.S. family-owned businesses. Many estates subject to the death tax are small or family businesses that are asset rich but cash poor; that is, their wealth is not sitting in liquid assets, such as stocks and bonds, but consists of physical assets, such as buildings, land, and machinery.[2] When the owner of a business dies and the heirs are forced to cough up 40 percent of the business’s value, they often have to sell off assets, or even the entire business.[3] These businesses are often sold to large corporations with weak ties to the local business community—which has resulted in disastrous consequences for the people who live in those communities.[4]

A previous Heritage Foundation study documented some of the devastating effects the estate tax has on individuals and communities.[5] Companies under threat of being destroyed by the death tax range from a minority-owned shrimp business in Biloxi, Mississippi, to one of the best-managed and most popular Section 8 housing properties in New Orleans. Jobs and vital community investments are likely to disappear when companies such as Hancock Lumber, a sixth-generation family business in Casco, Maine, or the Drummond mining company in Sipsey, Alabama, are forced to pay the death tax.

Even if a family does come up with the money to pay the estate tax, family members are left with significantly less capital to sustain and grow their business. Businesses that cannot expand cannot hire or invest. The result is fewer jobs, lower productivity, and smaller incomes for American workers.

The burden of taxation on U.S. small businesses is already extraordinarily high. The majority of U.S. business owners face very high marginal tax rates during their working years, often close to 50 percent when counting payroll taxes.[6] A 40 percent tax on what is left when an owner dies is just piling on even more.

Not Just a Tax on the Wealthy

It is not just the wealthy who are harmed by death taxes. Capital is a key component of workers’ productivity. The death tax, by reducing the level of capital available to workers, means that workers will have less opportunity to increase their own productivity, income, and wealth over their lifetimes.

Although the death tax is defended at times on the grounds that it reduces income inequality in the U.S., it actually has a negligible impact on income inequality and other forms of inequality. A recent report by the Joint Economic Committee points to the following studies and findings: Alan Blinder, former Vice Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, found that only about 2 percent of income inequality can be explained by inherited wealth; of the 400 wealthiest people on Forbes’s 2011 list, about 70 percent of those individuals were self-made, meaning they built their own fortunes, rather than having had help from family or inheritances; and, according to the 2011 U.S. Trust Survey, 73 percent of individuals with over $3 million in net worth did not accumulate any of their wealth through inheritance.[7]

The death tax also encourages Americans to consume more and invest less. Why save if the government is ultimately going to confiscate 40 percent of your estate? All told, lower savings and investment lead to a less dynamic U.S. economy. The immediate consumption and foregone savings means that private businesses have less money to invest, which results in fewer American jobs and lower wages.

Little Bang for the Buck

Estimates of the impact of the death tax on federal revenue vary significantly. Static estimates that include only the direct receipts from the tax itself show a small positive revenue gain. The Congressional Budget Office, for example, projects that the federal estate (and related gift taxes) will generate a modest 0.65 percent of federal tax revenues between 2015 and 2024 under this scoring method.[8]

On the other hand, dynamic models that take into account distortions in economic activity caused by the tax show smaller net receipts from the tax or even negative impacts on federal revenue. The American Family Business Foundation found, for example, an $89 billion loss in revenue over the 2011–2021 period due to the existence of the death tax.[9]

This Backgrounder concludes that the true figure almost certainly lies somewhere between these two estimates. Using dynamic scoring that incorporates only one transmission channel (the impact of the death tax on the cost of capital and thus on future investment and job growth), we estimate that death tax receipts under current law will account for only 0.5 percent of federal revenue between 2015 and 2024.[10]

What all these studies conclude is that the revenue impact of the death tax is negligible. At best, the tax delivers little bang for the buck; at worst, it costs the federal government more than it gains.

While the death tax accomplishes little in the way of revenue or income redistribution, it does generate significant economic harm. At a minimum, the death tax reduces savings and investment and leads to lower levels in the overall stock of capital in the economy. It also destroys small and family enterprises, at the least reducing their size and ability to grow, both reducing jobs and potentially increasing inequality.[11] This Heritage study estimates that because of the death tax, the American economy generates 18,000 fewer jobs each year than it would if the tax were repealed.

Repeal the Death Tax, Expand Economic Opportunity

Federal policy leaders should eliminate the death tax. The economic harm imposed by the continuation of the federal death tax is not worth the small amount of revenue it might generate. Ideally, of course, Congress would reform the entire tax system and eliminate all taxes on capital, including capital gains and dividends. Absent that, repeal of the death tax is an important intermediate improvement of the tax code.

—John L. Ligon is Senior Policy Analyst and Research Manager, Rachel Greszler is Senior Policy Analyst in Economics and Entitlements, and Patrick D. Tyrrell is Research Coordinator, in the Center for Data Analysis, of the Institute for Economic Freedom and Opportunity, at The Heritage Foundation.

Appendix

Simulation Conclusions and Methodology

Heritage Foundation economists in the Center for Data Analysis (CDA) estimated the impact of a full repeal of the federal estate tax (and related gift taxes), effective January 1, 2015, on the economy and federal budget over a 10-year forecast horizon, from 2015 to 2024.

To conduct this simulation analysis, CDA economists employed the IHS Global Insight (GII) September 2014 Quarterly Macroeconomic Model. The GII model is widely used by Fortune 500 companies, prominent federal agencies, and economic forecasting departments. The methodologies, assumptions, conclusions, and opinions in this analysis are entirely the work of CDA economists and do not necessarily reflect the views of the owners of the model.

To begin, CDA economists used estimates by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) of federal estate and gift taxes from 2015 to 2024, which average $26.1 billion.[12] Thus, repeal of the federal estate and gift taxes are expected to reduce static federal revenues by an average of $26.1 billion over the 2015–2024 period (beginning as $21.5 billion in 2015 and rising to $30.5 billion in 2024).

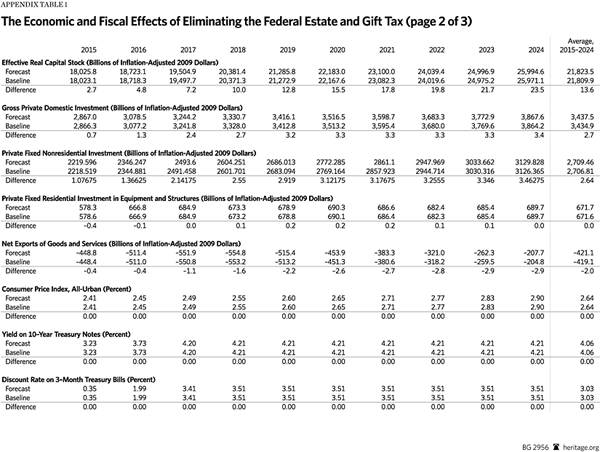

The estate tax is a tax on capital. To capture the macroeconomic impact of eliminating the estate and gift tax, CDA economists simulated the reduction in taxes as a reduction in corporate interest rates as measured by the yield on AAA-rated corporate bonds and BAA-rated corporate bonds. Previous studies show a direct link between wealth-transfer taxes and investment yields: A 2000 study by MIT economist James Poterba estimated that federal estate and transfer taxes add at least 1.3 percent to the cost of owning capital in the United States;[13] a 1996 study by former CDA director William Beach estimated that the federal estate and transfer taxes add 3 percent to the cost of owning capital.[14] Based on current estate-tax-law parameters, CDA economists targeted adjustments to the add factors[15] on the series on AAA-rated corporate bonds and BAA-rated corporate bonds by 2.5 basis points. Using the add-factor adjustment to these economic series allows the series to remain endogenous to the model as it solves. This parameter value lies between the estimates by James Poterba[16] and William Beach[17] relating to the economic effect that the federal estate tax likely has on the cost of capital.

According to the GII model, a full repeal of the federal estate tax (and related gift taxes) would result in a stronger U.S. economy over the forecast horizon. The policy change is assumed to be implemented in 2015, and over a 10-year forecast horizon (2015–2024) induces $46 billion in inflation-adjusted economic growth. The stronger economy would generate an average of 18,000 private-sector jobs annually in the U.S.

Beyond a top-line stronger U.S. economy, overall real net worth of American households would increase a little more than $300 billion annually over the 10-year policy forecast horizon.[18] Nearly all of this increase in household wealth would occur in household holdings of financial assets. Over the forecast period there is an average annual increase in real private-sector domestic investment of nearly $3 billion, and an average annual increase in the real capital stock of $14 billion.

The macroeconomic simulation does not model the impact of additional federal policy reform that could lead to a stronger economy. This scenario simulates the likely economic effects of this one particular policy change assuming no other changes to federal policy. Thus, any changes in government spending that may occur as a result of changes in the economy are not included. Likewise, although the model shows an increase in non-estate and gift tax revenues, we do not model the effect of those revenues as a change in the federal spending or taxation.

As mentioned, the CBO has estimated that, on a static basis, the repeal would result in a loss of $261 billion in federal tax receipts over 10 years. The results of the dynamic simulation, which only include the direct impact of repeal on the cost of capital, show an offsetting increase of $33 billion over the 10-year period. Although this still suggests a $228 billion reduction in federal revenues, the simulation does not attempt to quantify the additional federal tax revenues that would be gained as a result of more capital being subject to the capital gains tax or the additional federal tax revenues that would be gained as a result of reduced distortions currently generated by the death tax. Federal government spending is estimated to increase slightly relative to the baseline due to the growing economy, but this spending is offset by the additional federal tax revenues.

Potential Shortcomings in Simulation Modeling

As with all economic forecasts, this analysis is an estimate, and ultimately cannot predict the precise impact of a full repeal of the estate tax. The findings of this dynamic simulation analysis are consistent with economic theory and empirical findings in both expected and actual sign changes on macroeconomic variables, even though for all intents and purposes the exact magnitude of changes in economic variables may be higher or lower.

While some weaknesses are inherent in any forecast, this particular estimate may overestimate or underestimate true economic effects in the following ways:

- The analysis incorporates the added capital gains tax revenues that would come from the increase in capital stock, but it does not incorporate other added capital gains tax revenues that would come from some capital being taxed at the capital gains tax rate that would otherwise have been taxed at the estate tax rate. Because capital passed on at death is often not realized in the short term, it is difficult to estimate the size or timing of eventual capital gains tax revenues that will accrue from such taxes. In this respect, this analysis overstates the net change in federal tax revenues (the net loss would be lower than the projected decline of $228 billion, or 0.57 percent of federal tax revenues).

- This analysis estimates a repeal of the federal estate and gift taxes with no change in the current carryover treatment of inherited capital. This would leave an inequity in capital gains taxation between inherited and non-inherited capital. Inheritances subject to the estate tax currently receive a step-up in basis, meaning that the basis for inheritors paying the tax is set at the current market price, as opposed to the price paid by the deceased owner. This prevents another layer of double taxation on transferred assets. However, if the estate tax were eliminated, policymakers may replace the current step-up in basis with a carryover basis, meaning that inheritors would pay capital gains taxes (when they choose to sell their inherited assets) based on the original purchase price of the assets, as opposed to the value when they inherit them. If policymakers were to replace the step-up in basis with a carryover basis, the actual loss in revenue from eliminating the death tax would be significantly lower than projected by this analysis and might, very well, even result in a net increase in tax revenues.