Congress has set the federal government budget on a dangerous trajectory and must take corrective action now. Taxpayers pay enormous amounts of money to the government, and the government borrows additional huge amounts of money. The government uses the taxes that it collects and the money that it borrows to pay for excessive spending, including spending for ever-expanding entitlement programs. As America’s national debt skyrockets, so does the interest the government must pay on that borrowed amount. Americans can no longer afford and should no longer tolerate the government’s excessive spending and astronomical debt.

As of August 20, 2015, the U.S. national debt hovered at $18.1 trillion.[1] According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), if the government remains on its currently planned trajectory, it will spend another $7 trillion more over the next 10 years than it will receive in taxes, piling on even more debt.[2]

The CBO says that “net interest costs are projected to nearly quadruple from $227 billion in 2015 to $827 billion in 2025.”[3] That $827 billion in interest that the government must pay in 2025 represents 59 percent of the entire amount of discretionary spending projected for the government in 2025.[4] In fact, the government projects that it will spend more to make its interest payments on its debt in 2025 than it will lay out for the nation’s defense in that year.[5] The country cannot and should not sustain the current course of excessive spending and borrowing.

In the long run, Congress needs to drive down federal spending, including through reform of entitlement programs, to a balanced budget while maintaining a strong national defense and without raising taxes. While Congress cannot solve everything at once, it can and must take the opportunities it faces in September through December of 2015 to cap and cut spending, move to budget balance, and take steps toward tax reform that will allow the free market to grow the economy.

Congress faces the duty to appropriate funds for government operations, address the statutory debt limit, reform and fund transportation programs, and extend or end various expiring provisions of tax law. In performing those duties in the coming months, Congress should:

- Put the budget on a path to balance. Cut spending and get on a path to balance the budget before considering any increase in the debt limit.

- Establish spending caps that include mandatory spending. Put mandatory spending programs on a budget and adopt an expenditure limit on all non-interest spending.

- Move toward a balanced budget amendment. The nation needs a balanced budget requirement in the Constitution to enforce fiscal sustainability.

- Adopt a full-year continuing resolution (CR) for non-defense programs before the end of this year. The CR should be set at the levels established in the Budget Control Act (BCA), with the necessary policy changes, and should fully fund defense through the normal appropriations process.

- Enact highway funding reform focused on the states and private sector. Devolve surface transportation funding to the private sector and local governments.

- Do not reauthorize bad tax extenders. Move the tax code closer to an ideal system while making fundamental reform easier to achieve.

Congress should approach each of these matters based on five overarching principles.

- Congress should build on the fiscal achievements that have been made with respect to discretionary spending by expanding the spending cap to cover mandatory spending and entitlement programs.

- Congress should live by its own budget plan and adopt reforms that put it on a path to balance within 10 years.

- Congress should not increase taxes and should fully fund defense.

- Congress should use the appropriations process for funding government operations to address specific policy concerns.

- Congress should address each of the issues separately. Both the debt limit and the annual funding of government operations are critically important issues that require much debate and scrutiny to ensure that resources are allocated appropriately and that the nation’s priorities are reflected correctly. Furthermore, the federal surface transportation program is in desperate need of reform, a need that is reflected in the impending exhaustion of the trust fund used in its financing.

In implementing these principles through the actions discussed below, Congress should cut and cap spending, move to a budget balance, and take steps toward tax reform that helps to bring economic growth. These actions by Congress would strengthen America’s economy, society, and defense.[6]

Cut and Cap Spending: Adopt a Path to Balance Before Considering the Debt Limit

Congress should adopt a two-pronged strategy now to put the U.S. budget on a path to balance before the end of the decade, and it should do so before considering whether to raise the debt limit.

First, Congress should enact the spending reforms included in its fiscal year (FY) 2016 congressional budget resolution (S. Con. Res. 11, 114th Congress).[7]

Second, Congress should adopt a spending cap, enforced through sequestration, to control all non-interest mandatory spending as an important part of putting federal spending on a path to balance. Such a spending cap would strengthen the debt limit by limiting non-interest spending—the driver of growing deficits and debt and something that Congress can directly control. It would also build on the success of the Budget Control Act by expanding its spending cap, enforced by sequestration, to include those parts of the budget that present the greatest threat to the nation’s fiscal health.

The Debt Limit: An Important Fiscal Policy Tool. The debt limit is the legislative limit on the amount of national debt the U.S. Treasury may issue to meet federal payment obligations.[8] The limit was reinstated on March 16, 2015, after Congress had temporarily suspended it in 2014. Now at $18.1 trillion, debt subject to the limit exceeds what the U.S. economy produces in goods and services as measured by gross domestic product (GDP).[9]

The Constitution grants the power to borrow to Congress, thereby denying it to the President as an additional check on public debt. The statute setting the debt limit is part of how Congress retains some of its authority to borrow money on the credit of the United States. As Michael W. McConnell of Stanford Law School explains:

Article One, Section Eight, Clause Two allows Congress to borrow money on the credit of the United States. It imposes no limit, but note that granting this power to the legislative branch denies it to the executive. Under the unwritten British Constitution prior to the Glorious Revolution, the king could borrow money as a matter of his own prerogative authority, which kings frequently did, with disastrous results.

The British experience in the century prior to the Constitution suggested that parliamentary control over borrowing was a real, substantial, and effective check on excessive public debt. And so the framers imitated that. Some people thought, last summer, that President Obama should raise the debt ceiling on his own authority, which would have violated this fundamental constitutional principle. But Obama is only president of the United States. He is not King Charles II.[10]

A vote to increase the debt limit is a highly public affair and an opportunity to revisit how the actions of government affect spending and deficits. Without a rule imposing a periodic routine examination of finances, Congress is more likely to disregard its actions until some future fiscal crisis forces drastic and especially painful action. Just as an occasional check on blood pressure can lead to a course correction and avoid a massive heart attack, the debt limit should be used to motivate lawmakers to check and correct the nation’s fiscal path.

Politically Motivated Debt Limit Strategies. Politicians have figured out ways to manipulate situations or have found loopholes that allow them to give the impression of doing something while in reality maintaining the status quo. To avoid the political pain of allowing for increases in the debt limit without doing the hard work of cutting federal spending, Congress has employed various strategies to establish political cover to increase the debt limit. What all of these strategies have in common is that they allow lawmakers to neglect dealing with the issue at hand: overspending. Two recent examples are suspension and the resolution of disapproval.

Suspension. Since passage of the Budget Control Act of 2011, Congress has failed to put a current-dollar limit on the debt, opting instead to suspend the debt limit until a certain future date. A debt limit suspension technically renders the debt limit statute inoperative.

A suspension lifts the debt limit and allows for unlimited borrowing by the Treasury through a certain date. In many ways, it is like giving the Treasury a credit card with no limit or a blank check to be cashed against younger and future generations.[11] When the debt limit suspension ends, the debt limit is automatically increased to reflect the amount of borrowing that occurred since the last debt limit bound the Treasury. However, because there is no actual dollar-denominated limit on the national debt during the suspension period, taxpayers will not know for certain just how much more borrowing Congress authorized until after the fact.

This is the idea behind the suspension. Lawmakers do not have to confront their constituents’ wrath for increasing the debt limit by a specific dollar amount—$1 trillion, for example—without making spending cuts of at least the same size or greater.

The argument that suspension gives lawmakers more control as to when to schedule a more opportune legislative moment to enact spending control is not valid. Given unpredictable cash-flow operations and the Treasury’s authority to resort to so-called extraordinary measures, or authorized debt limit loopholes, Congress has very little control over when Treasury’s borrowing authority is fully exhausted and the debt limit is to bind.[12] Moreover, recent history shows that Congress does not in fact enact spending control following suspensions of the debt limit.

The Resolution of Disapproval. This proposal would allow the President to raise the debt limit unilaterally while allowing for a congressional resolution of disapproval. The idea behind this rule is that Congress could shift the blame for raising the debt limit to the President while at the same time going on the record for voting against a debt limit increase. The resolution of disapproval is designed to provide political cover for lawmakers to do the wrong thing: increasing the debt limit without first getting spending under control.

The Budget Control Act included something similar to this proposal. It scheduled automatic debt limit increases into law unless Congress passed a resolution of disapproval that the President signed. However, the Budget Control Act also included a mechanism to cut spending by the amount by which the debt limit was scheduled to increase—the so called Boehner rule. The original proposal contained no such stipulation.

Adoption of the proposal would effectively surrender Congress’s authority over the debt limit to the executive. It also would eliminate Congress’s ability to leverage debt limit votes to exercise the power of the purse in making vital course corrections when confronted with the results of unsustainable spending decisions made by past Congresses or by executive orders.

A Wakeup Call to Control Spending. The debt limit is most useful if it encourages lawmakers to take action on implementing fiscal reforms. Hitting the debt limit confronts Congress and the Administration with the results of unsustainable budget decisions: massive and growing amounts of debt. This should motivate lawmakers to adopt spending cuts and other budget reforms to address out-of-control spending and debt.

It is not uncommon for lawmakers to use the statutory debt limit as leverage to enact deficit-reduction legislation. Examples include the Budget Control Act of 2011, which raised the debt limit in exchange for dollar-for-dollar cuts in spending, and the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985 (Gramm–Rudman–Hollings), which raised the debt limit in exchange for a five-year plan to balance the budget.[13]

Congress should control spending before agreeing to consider any increase in the debt limit. The debt limit allows Congress to exercise its power of the purse in making vital course corrections when confronted with the results of unsustainable spending decisions. As such, it presents a decisive, action-forcing moment for Congress to take charge of the automatic spending increases that are driving the U.S. spending and debt crisis.

Every few months, the Congressional Budget Office releases a new report projecting deficits and debt over the next decade. Despite a short-term improvement in the 2015 budget year over the previous year, the CBO projects that deficits and debt will grow to alarming levels over the next decade and beyond. The CBO projects the 2015 deficit at $425 billion, down slightly from the $485 billion level recorded in 2014. This marks the end of a three-year period—following the great recession and its stimulus excesses—of declining deficits.[14] The deficit for 2016 is expected to come in at $414 billion, lower than the previous year’s level, and then rise steeply from there. According to the CBO’s more realistic alternative fiscal scenario, the deficit will exceed $1 trillion before the end of the decade.

Growing spending, especially on entitlement programs and interest on the debt, is driving increases in the deficit and the debt. The CBO projects that spending in 2025 will be $2.3 trillion compared to this year—rising from a projected $3.7 trillion in 2015 to $6.0 trillion in 2025.[15] The CBO attributes this increase in spending to the aging of the population, rising health care costs, and a significant expansion in eligibility for federal subsidies for health insurance (Obamacare).

The major health care programs (Medicare, Medicaid, Children’s Health Insurance Program, and Obamacare) are driving 32 percent of the increase in spending over the next decade, followed closely by the Social Security program at 28 percent and interest on the debt at 24 percent. All other spending programs will be responsible for the remaining 16 percent of the projected increase in spending.[16]

When past Congresses authorized Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, they did not project what the programs would cost several decades later. Entitlement programs are prone to balloon after the first decade, which is the period for which congressional scorekeepers generally establish cost projections. Obamacare is a recent example: The Congressional Budget Office predicted that the Obamacare statute would reduce the deficit within one decade of its enactment, while the Government Accountability Office (GAO) predicted that the law would add several trillions to the deficit over a 75-year period.[17]

Even if Congress tried to account for the cost of program spending for several generations, forecasters are often unable to predict expenditures very far into the future with any real accuracy. The debt limit presents Congress with a focused opportunity to implement reforms that control the growth in spending programs enacted in the past.

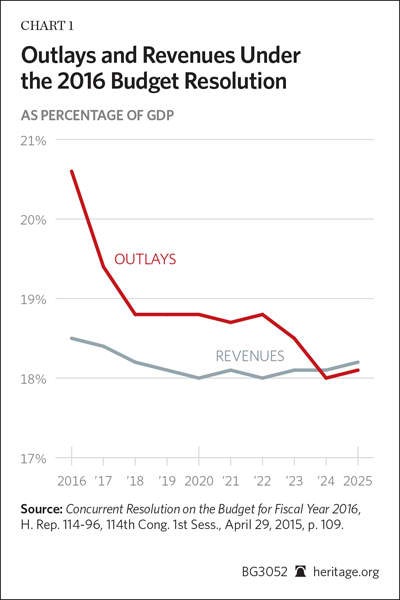

Enact Congressional Spending Reforms. In May 2015, for the first time in more than five years, Congress passed a congressional concurrent budget resolution. The plan would balance the budget by 2024—but only if Congress enacts additional enabling legislation to carry out the plan set forth in the budget resolution.

Congress’s budget plan merely establishes a blueprint for balancing the budget. Without separate legislation to implement the called-for reforms and spending cuts, the plan is simply a collection of non-binding messages about policy priorities. The debt limit presents Congress with a legislative opportunity to put its budget into force.

Despite the shortcomings of this year’s budget plan, enacting several of its reforms would be an important step on the path to a balanced budget. Along with the enactment of these reforms, Congress should also adopt an aggregate spending cap and a balanced budget requirement (both discussed below). Congress should pursue the following reforms based on its budget resolution:

-

Repeal Obamacare. The budget agreement proposed to use the reconciliation process to repeal Obamacare. As spending on health care entitlements, including Obamacare, Medicaid, Medicare, and others, drives about one-third of the projected spending increase over the next decade, addressing the growth in health care spending, starting with Obamacare, is critical to controlling the debt.

Full Obamacare repeal is an essential first step toward controlling growing health care entitlement spending and would pave the way for market-based and patient-centered health care reform that empowers individuals. On the way to accomplishing full Obamacare repeal, Congress should embark on a reform agenda that moves the nation’s health care systems toward patient-centered, market-based approaches in which individuals, not the government, are the key decision makers in the financing of health care.[18]

-

Reform Medicare. The concurrent budget resolution proposed significant savings from Medicare reform. Although the House resolution included the important transition to a Medicare premium-support model, the Senate did not endorse this specific reform. The Senate and the final concurrent congressional budget resolution instead asked the appropriate committees to develop the reforms needed to meet the savings target.

To achieve the savings in the budget resolution and help put the budget on a path to balance, Congress should:

- Gradually and predictably increase the age of Medicare eligibility to conform to Social Security’s retirement age, beginning after five years.

- Increase Part B and Part D premiums for seniors from 25 percent to 35 percent over five years.

- Income-adjust Parts B and D premiums for higher-income enrollees, asking individuals with $55,000 in income and families with $110,000 in income to pay a larger share of their Medicare premiums, and phase out premium subsidies for individuals with $110,000 in income, or for families with $165,000 in income, immediately.

- Immediately replace the Medicare Advantage payment formula with pure market-based bidding for the government contribution.

- Phase in Medicare premium support in three years, five years sooner than proposed in the House budget resolution.

-

Reform Medicaid. The congressional budget resolution would provide a capped allotment for Medicaid and give states greater flexibility in designing benefits and administering the program for beneficiaries. These changes would affect only able-bodied beneficiaries, leaving the funding of services for the low-income elderly and disabled unchanged. Congress should begin to make these changes now.

Ultimately, however, Medicaid needs structural reform that entirely reverses the perverse incentives created by the program’s open-ended funding and allows states to tailor their Medicaid programs to fit the needs of their specific populations. In particular, Congress should enable Medicaid enrollees to use their Medicaid dollars to purchase private coverage of their choice and control decisions about their care.[19]

-

Reform welfare. While the congressional budget resolution provides few details regarding its strategy to control welfare spending in the U.S., it does propose to reduce the rate of growth in welfare spending significantly compared to current law. Welfare spending has been rising rapidly for decades. In FY 2013, government (federal, state, and local) spent a total of $950 billion on means-tested welfare. This is roughly a sixteenfold increase since the government’s War on Poverty began back in the 1960s. Overall, government has spent $22 trillion on welfare over the past five decades.

To get the U.S. welfare system back on track, proper policy must be put into place. Welfare reform should focus on promoting self-sufficiency through work as well as on curbing out-of-control spending. The vast majority of the government’s 80 means-tested welfare programs fail to include a work requirement for able-bodied adults. Programs such as food stamps should require that able-bodied adults work, prepare for work, or look for work in exchange for receiving assistance. Also, total means-tested welfare spending on the government’s 80 programs should be scaled back and capped. This would require policymakers to prioritize spending among the vast array of welfare programs and put welfare spending on a more prudent course.[20]

Enact a Statutory Spending Cap Enforced by Sequestration. The debt limit debate of 2011 was resolved when Congress and the President agreed to enact the Budget Control Act, which put a cap on discretionary spending, including both defense and non-defense spending. Spending caps can motivate Congress to prioritize among competing demands for taxpayer money and, if designed properly, can help to curb excessive spending growth over the long run. Representative Kevin Brady (R–TX) recently reintroduced the Maximizing America’s Prosperity Act (H.R. 2471), which would impose a statutory spending cap in line with the spending targets established in Congress’s budget resolution, enforced by discretionary sequestration.

Sequestration has been effective in getting Congress to do what it for too long failed to do: cut spending. By the end of 2013, federal spending had fallen for two straight years for the first time since the end of the Korean War. While some of those reductions were the result of an improving economy and the winding down of temporary, excessive stimulus spending, the Budget Control Act and sequestration did succeed in limiting discretionary spending. Federal agencies (with the help of Congress) for the most part were able to cope with the $85 billion in automatic cuts by prioritizing their budgets. As The Wall Street Journal put it, “A testament to the success of the [sequestration] caps is that nearly every Democrat and spending lobby in Washington is desperate to get rid of them.”[21]

Although its across-the-board nature has its flaws, sequestration is an important process mechanism that often succeeds in bringing lawmakers to the table to find common solutions. It is no accident that lawmakers do not tackle most government programs that grow on autopilot, except those with so-called fiscal cliffs. Examples abound, including Medicare “doc fix” legislation,[22] the Highway Trust Fund (HTF) shortfall patch,[23] and the imminent exhaustion of the Social Security Disability Insurance trust fund,[24] among others.

Budget experts across the ideological spectrum recognize that Congress very rarely acts unless forced to act by a legislative action deadline with a painful enforcement mechanism. This is why a bipartisan group of experts who participated in the Brookings–Heritage Fiscal Seminar agreed on three key budget process steps to motivate lawmakers to make entitlement spending reforms:[25]

- Enact a real long-term budget for entitlements like Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security that limits their growth and their current ability to preempt all other spending;

- Require review and action on the entitlement budget at least every five years to keep spending within budgeted amounts, enforced by automatic triggers; and

- Reveal the programs’ long-term costs and consider them when budget decisions are made.

Such process changes are key to paving the way for much-needed debate and deliberation on the structure and financing of entitlement programs.

One Cap for All Non-Interest Budget Authority. One key failure of reinstituting the discretionary spending caps enforced through sequestration under the BCA is that the caps excluded a large portion of mandatory spending, the largest and fastest growing portion of federal spending. Moreover, the BCA provides a number of loopholes that are used to circumvent the caps.[26]

In order to motivate lawmakers to tackle entitlement reform, one promising approach would include all non-interest budget authority under one spending cap. Such a cap would include all discretionary and mandatory spending, except interest on the debt. Interest on the debt would be excluded because it depends in part on interest rates, inflation, and the maturity and structure of outstanding securities—factors largely outside of Congress’s control. A statutory spending cap would encourage lawmakers to prioritize federal spending, enable them to say “no” to special interests, and help to protect American taxpayers from wasteful spending burdens.

Spending caps could be implemented in a number of different ways.[27] It is important that any limit on spending be simple to understand so that compliance with it can be monitored easily by the public. It is equally important that simplicity not come at the price of political stability over time. As Alexander Hamilton wrote in his First Report on Public Credit, “exigencies are to be expected to occur, in the affairs of nations, in which there will be a necessity for borrowing…. [L]oans in time of public danger, especially from foreign war, are found an indispensable resource, even to the wealthiest of them.”[28]

The federal budget contains many automatic stabilizers that increase spending and deficit pressures during economic downturns, making a simple spending cap that provides little flexibility in times of economic distress or as a matter of national security a political challenge. More sophisticated statutory or constitutional spending limits seek to balance the budget or maintain a steady, sustainable fiscal course across a business cycle.[29]

Lawmakers should adopt a statutory spending cap that encompasses all non-interest outlays and achieves budget balance, given current projections about the economy, revenues, and interest costs, by the end of the decade.[30] Spending would then be capped at a level that maintains balance, allowing for certain annual adjustments. In the long run, during periods of normal economic activity and absent exigent national security demands, the spending cap should grow no faster than the U.S. population and inflation, similar to fiscal rules currently in place in many U.S. states. The cap should bind more stringently when debt or deficits exceed specific targets. Debt below 60 percent of GDP and deficits below 2 percent of GDP are commonly accepted as fiscally stable by a wide range of economists. For such a spending cap to be effective at motivating lawmakers to adopt spending reforms that eliminate structural deficits in the U.S. budget, enforcement by sequestration would be necessary.

Sequestration was first authorized by the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985 (BBEDCA, or Gramm–Rudman–Hollings Act). The 2011 Budget Control Act included a sequestration based on the rules established in the BBEDCA, including its exemptions. Congress should review the BBEDCA and its exemptions in light of current budgetary pressures.[31] In particular, Congress should not exempt most mandatory programs from sequestration. Mandatory spending is the fastest-growing type of spending and for the most part lacks any budgetary control.

Among the programs currently exempt from sequestration, Congress should consider including under sequestration the following:

- Social Security cost-of-living adjustments;

- The premium assistance tax credits and cost-sharing subsidies;[32]

- Federal aid to highway programs;

- Certain programs administered by the Veterans Administration (VA), including VA administrative costs;

- Refundable tax credits, including the Earned Income Tax Credit and the refundable portion of the Child Tax Credit;

- Child Nutrition Programs;

- The Children’s Health Insurance Program;

- Temporary Assistance for Needy Families;

- Federal Pell Grants;

- Medicaid, except for elderly and disabled care;

- The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; and

- Grants in Aid to Airports.

The Continuing Resolution: Adopt a One-Year Continuing Resolution to Fund FY 2016 Operations

Federal funding for most government agencies and departments expires on September 30, 2015. The congressional budget process calls on Congress to pass 12 individual spending bills before that date to fund the federal government’s operations. However, this year, presidential threats to veto spending bills containing policy riders and spending of which the President disapproved have ground the appropriations process to a halt.[33] Some in Congress seek to pressure conservatives and others who seek to protect taxpayers and cap and cut federal spending to break the bipartisan spending caps that limit the discretionary budget to $1.016 trillion in FY 2016 (not including war or emergency funding).[34] That limit has already been changed twice: by the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (which reduced the caps by $6 billion over FY 2013 and FY 2014) and the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 (which increased the caps by $64 billion over FY 2014 and FY 2015). Congress must stand firm. The spending caps adopted in the Budget Control Act represent a victory for Americans that was accomplished with bipartisan support, including support from President Barack Obama.

To ensure the maintenance of the cap, Congress should adopt a full-year continuing resolution for non-defense programs and fully fund defense through the normal appropriations process before the end of this fiscal year at the levels established in the BCA and reaffirmed in the congressional budget resolution passed by both chambers this spring. While appropriations continuing resolutions are far from ideal policy, under current circumstances Congress can best serve the American people by holding to the spending levels in current law. The alternative is much worse: greater deficit spending that puts America deeper in debt, grows government, and closes off opportunities for conservative reform.

Congress Should Enact Reforms Through “Anomalies” and Legislative Provisions. The Constitution unequivocally grants Congress the exclusive authority to provide money for the functions of government through its lawmaking power.[35] In Federalist No. 58, James Madison wrote that budgetary powers were a critical element in maintaining freedom: “The power of the purse may, in fact, be regarded as the most complete and effectual weapon with which any constitution can arm the immediate representatives of the people, for obtaining a redress of every grievance, and for carrying into effect every just and salutary measure.”

Congress provides money on an annual basis for the routine functions of government through 12 appropriations bills. However, if those bills are not enacted, continuing resolutions can be used to provide resources based on the current operations of government for some specified amount of time. Under a continuing resolution, Congress can exercise its unique privilege to address “every grievance” and to provide for every “salutary measure” by adding provisions to the continuing resolution. These provisions, commonly called “anomalies,” can restrict funds for certain uses or designate specific funds for different purposes.

The full-year continuing resolution (i.e., continuing appropriations for the government through September 30, 2016) should include the following anomalies and legislative provisions:

-

Adjust for the use of budget gimmicks. In recent years, Congress has used more budget gimmicks (such as changes in mandatory spending programs, or CHIMPs) and rescissions, the cancellation of previously authorized funds, to mask higher annual spending than allowed under the BCA’s spending limit. As a consequence of using inappropriate accounting methods to evade the BCA limit, a continuing resolution for non-defense programs would spend $7.1 billion above the BCA spending limit for non-defense.[36] Therefore, the continuing resolution should include a 1.4 percent across-the-board reduction in non-defense spending programs to honestly appropriate to the spending limit.

-

Defund Planned Parenthood. Recent information that has surfaced shows unethical and abominable conduct by Planned Parenthood, the nation’s largest abortion provider, involving the sale of organs from aborted babies. Planned Parenthood has also been accused of Medicaid fraud, having paid over $4 million in a 2013 settlement.[37] The CR should prohibit any federal funds from going to the Planned Parenthood Federation of America and the organization’s affiliates.[38]

-

Do not reauthorize the Export–Import Bank. The charter of the Export–Import Bank (Ex–Im) expired on June 30, 2015, but proponents are intent on securing reauthorization. The bank provides discount financing to foreign firms and foreign governments for the purchase of American exports. The program primarily benefits multinational corporations and puts unsubsidized U.S. firms at a competitive disadvantage and taxpayers at risk. Ex–Im provides taxpayer-backed financing for just 2 percent of U.S. exports. Subsidies for air transport comprise the vast majority of Ex–Im financing—primarily benefitting Boeing.

Ex–Im was capitalized with $1 billion in taxpayer dollars, and its financing is backed by the full faith and credit of the United States, which means that taxpayers are on the hook for any losses that the bank fails to cover with reserves. There is no shortage of private financing available. By law (12 U.S.C. 635f), the Ex–Im Bank is limited now to carrying out its “orderly liquidation.”[39]

-

Abolish the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau or, failing that, make it more accountable. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) was created in 2010 by the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act and imbued with unparalleled powers over virtually every consumer financial product and service. There is ample evidence that agency operations represent a radical departure from long-standing regulatory standards. The CFPB’s actions are constricting the availability of financial products and services and raising costs—all of which will undermine business investment and consumer credit.

The CFPB was designed to evade the checks and balances that apply to most other regulatory agencies. Although established within the Federal Reserve System, it operates independently and with virtually no oversight. CFPB funding is set by law at a fixed percentage of the Federal Reserve’s operating budget. This budget independence limits congressional oversight of the agency, and its status within the Fed also precludes presidential oversight. Even the Federal Reserve is statutorily prohibited from “intervening” in bureau affairs. The CFPB should be abolished or, at a minimum, put on budget so that it must seek appropriations from (and be accountable to) Congress.[40]

-

Prohibit funding for WOTUS rule. The CR should prohibit the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) from using funds to implement the final “waters of the United States” (WOTUS) rule. This controversial rule, published by both the Army Corps of Engineers and the EPA, would greatly expand the types of waters that could be covered under the Clean Water Act (CWA) from most ditches to so-called waters that are actually dry land most of the time.[41]

-

Rein in the EPA’s ozone standard. The CR should prohibit the EPA from making the current ozone standard of 75 parts per billion (ppb) any more stringent. The EPA has proposed making the standard as low as 70 ppb or 65 ppb and is even considering 60 ppb. This drastic action is premature. States are just now starting to meet the current 75 ppb standard. According to the Congressional Research Service, 123 million people live in areas that have not attained the current standards. In fact, 105 million people live in areas that are still considered nonattainment for the less-stringent 1997 ozone standard. When nearly 40 percent of the nation’s population lives in areas that have not met the current standard, adopting an even more stringent standard is at best premature.[42]

-

Maintain funding for Yucca Mountain. The Department of Energy (DOE) has stopped collecting the nuclear waste fee, as ordered by the D.C. Circuit Court, since May 2014. However, there are more than sufficient resources[43] in the waste fund to complete the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s (NRC) review of the DOE’s license application for a permanent nuclear waste repository at Yucca Mountain. The NRC has yet to complete a supplemental environmental impact statement on groundwater (which the NRC has begun and expects to complete in spring 2016),[44] public hearings, and other requirements such as securing land and water rights, agreements for flight restrictions over the facility, and reporting requirements.[45] The NRC anticipates that the process will cost another $330 million, an amount the President’s budget did not request.[46]

A continuing resolution should provide $50 million to the NRC for the next fiscal year. It should further stipulate, as the FY 2016 House Energy and Water Appropriations bill did, that no funds may be spent on any alternative nuclear waste management plan, notably the President’s shortsighted Strategy for the Management and Disposal of Used Nuclear Fuel and High-Level Radioactive Waste, unless and until Congress passes legislation specifying otherwise. Further, a continuing resolution should clarify that no funds may be used for “actions that irrevocably remove the possibility that Yucca Mountain may be a repository option in the future.”[47] Congress should bring to an end the Obama Administration’s refusal to carry out the Yucca Mountain laws.[48]

-

Prohibit any agency from regulating so-called greenhouse gas emissions. The Obama Administration has proposed and implemented a series of climate change regulations, pushing to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles, heavy-duty trucks, airplanes, hydraulic fracturing, and new and existing power plants. More than 80 percent of America’s energy needs are met through conventional carbon-based fuels. Restricting opportunities for Americans to use such an abundant, affordable energy source will only bring economic pain to households and businesses, with no climate or environmental benefit to show for it. The cumulative economic loss will be hundreds of thousands of jobs and trillions of dollars of GDP lost.

-

Open access to natural resource development. Open all federal waters and all non-wilderness, non-federal-monument lands to exploration and production for all of America’s natural resources. Congress should require the Department of the Interior both to conduct lease sales if a commercial interest exists (whether for offshore oil or for offshore wind) and to use its flexibility under its current authority (whether streamlining of red tape or lower royalties) to attract interest to federal lands.[49]

-

Lift the ban on crude oil exports. The Department of Commerce should change the definition of allowable exports, and the President should determine that exports are in the national interest. Ultimately, Congress should end the ban by reforming the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920, the Energy Policy and Conservation Act of 1975, and the Export Administration Act of 1979.[50]

-

Repeal the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS). By requiring fuel blenders to use biofuels regardless of the cost, the RFS has made most Americans worse off through higher food and fuel expenses. The higher costs paid by American families benefit a select group of special interests that produce renewable fuels. Tinkering around the edges will not rescue this unworkable policy. Moreover, the federal government should not mandate which type of fuel drivers must use in the first place. Congress should repeal the RFS.[51]

-

End renewable energy mandates in the Department of Defense. Such mandates undermine the incentive for producers of renewable energy to develop competitively priced products, thereby actually impeding the availability of alternatives to carbon-based fuels. In particular, under Section 2911(e) of Title 10 of the United States Code, the Defense Department is obligated to generate 25 percent of its electricity using renewable sources by 2025. This mandate, which is forcing the Pentagon to expend increasing resources on renewable energy rather than on military capability, should be ended immediately.[52]

The Highway Trust Fund: Devolve Surface Transportation Funding to the Private Sector and Local Governments

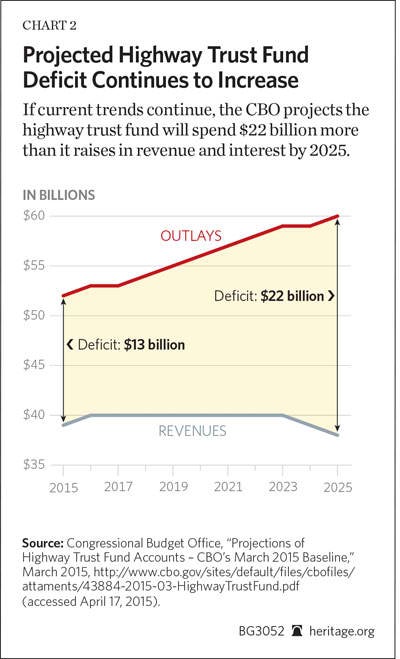

Congress most recently addressed the troubled Highway Trust Fund, which faced a $13 billion deficit for FY 2015, at the end of July when lawmakers passed a clean extension that authorized highway and transit programs through October 28.[53] To keep the Highway Trust Fund balance afloat for several months, Congress transferred $8.1 billion into the trust fund from the Treasury’s general fund while maintaining current policy, laid out in 2012’s Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act (MAP-21). This measure followed a two-month extension in late May, which required no immediate transfers into the fund because it was projected to maintain balances in excess of $5 billion (the minimum amount needed to maintain regular payments to states) through July.

The House originally favored a short-term measure and passed a precursor patch on July 17.[54] This measure, which led to the bill that became law, was another short-term bailout of the trust fund—the 34th since 2008—and did nothing to reform the spending problems that have led to a projected $168 billion shortfall over the next 10 years.[55] In addition, the bill relied excessively on tax increases and budget gimmicks to fund the $8.1 billion in transfers.[56] In short, it was another tax-and-spend provision that maintained the unacceptable status quo.

But before acquiescing to the short-term measure favored in the House, the Senate took a radically different route to addressing the Highway Trust Fund authorization. Senate Committee on the Environment and Public Works Chairman James Inhofe (R–OK) worked with Ranking Member Barbara Boxer (D–CA) to produce the Developing a Reliable and Innovative Vision for the Economy (DRIVE) Act, a comprehensive six-year bill that would authorize $350 billion in spending from the end of 2015 through 2021.[57]

In addition to authorizing Highway Trust Fund programs, the DRIVE bill included discretionary grants, Amtrak, and various other transportation programs. Rather than addressing the trust fund’s chronic overspending, it would exacerbate shortfalls by increasing spending on existing programs and establishing new ones. Inexcusably, the six-year bill contains only three years of funding offsets, leaving the $51 billion required to fund the remaining three years to be decided in subsequent Congresses or tacked on to future deficits.[58]

As Congress devises legislation to address highway funding following the expiration of authority in October, Members should start fresh to develop a truly viable, long-term solution. This section will discuss the problems plaguing the trust fund and a solution to the way the nation invests in infrastructure.

Federal Highway and Transit Spending in Need of Comprehensive Reform. The Highway Trust Fund will expend roughly $52 billion on highway and mass transit projects in 2015, although it will receive only $39 billion in revenues, primarily from the federal tax on gasoline and diesel fuels.[59]

The federal role in transportation has expanded far beyond national highway funding to include a host of other transportation areas that have nothing to do with the highway system or other national priorities. Non-highway projects are estimated to make up about 25 percent of trust fund outlays. These diversions include mass transit and other local projects such as sidewalks, bike paths, and beautification.[60] Mass transit spending alone accounted for over 17 percent of trust fund outlays in 2014, diverting motorists’ gas tax money to what should be local or regional projects. These expenditures are grossly disproportionate, given that only 5 percent of American workers use mass transit to get to work and just 2 percent of Americans’ personal trips are made by mass transit.[61] Even if that were not the case, these issues are best addressed at the local level.

The highway system has also expanded to include state and local roads that should be outside the jurisdiction of the federal government. The road mileage eligible for funding through the federal aid system has expanded to 1,077,777 route miles, compared to the 47,182 route miles that make up the Interstate Highway System.[62] A 2014 GAO report found that only $3 billion (6 percent) of Highway Trust Fund outlays was spent on the construction, reconstruction, or rehabilitation of major highway and bridge projects (those with costs of over $500 million).[63] This indicates a major shift away from the federal government’s traditional role—funding large projects that are truly national in scope—toward extensive involvement in projects that should be handled by states and localities.

Rather than align spending with revenues, Congress has bailed out the Highway Trust Fund with money from the general fund, totaling over $70 billion in transfers since 2008 (including the latest $8 billion transfer in July).[64] Currently, the Highway Trust Fund is projected to dip below critical levels ($5 billion) at the end of December, and the long-run picture looks worse: Before the most recent bailout, which did nothing to change spending patterns, the CBO projected a $168 billion shortfall over the next 10 years if current spending levels continue.[65] These trends make it clear that the trust fund has become a favored vehicle for overspending and pet projects in Congress. Fixing it requires comprehensive reform rather than perpetual bailouts or new streams of revenue.

A Responsible Way to Fund Surface Transportation. Congress should develop a proposal that will lead to real transportation funding reforms. In addition, transportation funding should be addressed on its own and should not be used as a bargaining gimmick in broader legislation that addresses appropriations, tax reform, or the debt ceiling. True reform would seek to accomplish two complementary priorities.

First, reforms should end the fiscally irresponsible overspending of money from the Highway Trust Fund, which will require billions in future bailouts.

Second, Congress should retool the current federal role in transportation to focus strictly on national priorities while giving states a greater role in funding their own transportation systems, free from the fecklessness of Congress and costly federal mandates.

The best plan proposed in Congress that accomplishes both of these goals is the Transportation Empowerment Act (TEA), introduced by Senator Mike Lee (R–UT) and Representative Ron DeSantis (R–FL).[66] The bill would reduce the federal gas tax from 18.3 cents to 3.7 cents per gallon over five years, limit spending to revenues, and prioritize funding of the Interstate Highway System. The plan would leave in place enough funding for the federal government to uphold its core mission of maintaining the genuinely national aspects of our transportation infrastructure. States would be responsible for funding their transportation infrastructure on their own terms, free from expensive federal mandates that make projects more expensive (such as the Davis–Bacon Act, which increases labor costs by more than 20 percent) and the uncertainty generated by inaction in Congress.[67]

States have already begun to take a greater role in funding their transportation systems. According to transportation analyst Kenneth Orski, 29 states have introduced measures to address their transportation revenue this year.[68] States are better equipped to address their transportation systems because they can craft measures to meet their own unique needs more effectively, are more accountable to users, and can bypass the legislative uncertainty inherent in the current system managed in Washington.[69]

Any short-term patch should be offset with spending cuts related to highways and transportation. Offsetting an extension from October 2015 until early 2017 would require roughly $15 billion.[70] Typically, Congress quietly and unwisely offsets new spending related to the Highway Trust Fund by reducing program spending unrelated to transportation or through new revenues. The Highway Trust Fund is not sustainable, and these short-term fixes do nothing to address the structural defects.

Repealing federal mandates that increase project costs, most notably the Davis–Bacon Act, could also yield significant savings by reducing the cost of federal projects (as well as generating savings for states).[71] Revenue increases and budget gimmicks should never be considered to offset a problem caused by expansion in the size and scope of spending on federal programs.

Instead of preserving the broken status quo with a poorly thought-out long-term bill, Congress could better serve the nation’s infrastructure by putting the states in the driver’s seat for transportation funding. Congress should work to implement TEA—or a similar solution that turns control back to the states—before the Highway Trust Fund continues into its projected fiscal morass and requires further bailouts.

Fixing a Broken Tax System: Pave the Way for Reform

Congress needs to reform the tax code to restore economic growth and opportunity for American families and businesses.[72] The current code levies high tax rates on productive activities, such as working, saving, investing, and taking risk; taxes investment multiple times at high rates; and picks winners and losers instead of allowing market forces to dictate outcomes. All of these factors depress wages and opportunities for American families.

The central purpose of tax reform is to alleviate this harm, restoring economic growth, increasing wages, and expanding opportunity. It does this by lowering marginal tax rates on families, businesses, investors, and entrepreneurs to increase their incentives for engaging in productive activities. It also establishes a correct tax base that does not tax savings and investment multiple times (known as a consumption tax base) and does not pick winners and losers.

Despite the very urgent need, fundamental tax reform is unlikely to occur before the end of this year. However, Congress will work on tax legislation during that time. All tax legislation that it passes should help it to accomplish its ultimate goal of overhauling the tax system. The impending tax extenders debate is an opportunity to do this.

Tax Extenders. It is likely that Congress will pass a tax extenders bill before the end of 2015. The package of approximately 50 tax-reducing policies expired at the end of 2014. Recently, the Senate Finance Committee passed a two-year extension that would retroactively renew them for 2015 and extend them through 2016.[73]

Some in Congress may feel the urge to restore the tax extenders simply because they have expired, but Congress has often allowed their expiration to linger deep into a year before renewing them late in the year. Once Congress allows the extenders to expire, it gains little from retroactively reinstating them, no matter when it does so. Hence, Congress should not use their currently expired status as an excuse to absolve it from handling them responsibly. There is still plenty of time for Congress to follow a process that will allow it to improve the tax code.

Go Through Policies One-by-One. The extenders are a hodgepodge of good and bad policies. Congress should go through each of the policies individually to determine which of them should be permanent and which should expire.[74] Policies that Congress should unquestionably eliminate because they particularly harm the ability to achieve tax neutrality include:[75]

- Credits for producing biodiesel and renewable diesel;

- Credits for producing or selling alternative fuel and alternative fuel mixtures;

- The Alternative Fuel Vehicle Refueling Property Credit (for installing alternative-fuel mechanisms);

- Income tax credits and excise tax credits for producing or using ethanol;

- The renewable electricity production credit and the optional investment credit (better known as the wind tax credits);

- Credit for construction of homes designated by the government as energy efficient;

- Credit for producing appliances designated by the government as energy efficient;

- Credit for improving the energy efficiency of existing homes;

- The new-markets tax credit;

- Empowerment-zone tax incentives;

- Enhanced mass transit subsidies; and

- Low-income housing provisions.[76]

Deemed Repatriation Only with International Reform. There is talk in Congress of replenishing the Highway Trust Fund and reforming the international portion of the business tax system at the same time.[77] International reform is an important part of tax reform because the U.S. is essentially the only developed country that taxes its businesses on their foreign earnings. Moving away from that antiquated worldwide system to a modern territorial one would be a boon for job creation and wage growth for U.S. workers.[78]

Such an improved policy, unfortunately, could be tied to replenishing the Highway Trust Fund through the taxation of U.S. businesses’ unrepatriated foreign earnings. Businesses pay tax on their foreign earnings when they bring them back to the U.S. Some estimate the amount of untaxed foreign earnings to be over $2 trillion,[79] although this figure is unofficial. Businesses have invested some of that money abroad while keeping some of it in cash. (The breakdown is unknown.) That large amount of untaxed earnings appeals to some in Congress who are eager to use the revenue that would result from taxing it immediately (deeming it repatriated and taxing it at a rate lower than under current law) to fill the Highway Trust Fund.

However, changes in the tax treatment of untaxed foreign earnings should be linked only to a move to a territorial system, not to anything else. Those earnings have accumulated overseas because the U.S. tax treatment of them is unfair and uncompetitive. Congress should only tax that deferred foreign income to undo that damage.[80]

If Congress uses part of the revenue raised from deemed repatriation of foreign earnings to offset the move to a territorial system and puts the other part in the Highway Trust Fund, the portion going into the Highway Trust Fund will be a tax hike. If Congress declares the money raised from deemed repatriation as offsetting the tax cut from moving to a territorial system but directs the money to the Highway Trust Fund, it will likely be double-counting the funds.

Fundamental tax reform, or even business-only tax reform, would be difficult in the time remaining in the current session of Congress. Reforming the international portion of the business system is sensible if it can be achieved in the coming months where broader reforms are not. International reform can be broken off from those broader reforms and accomplished separately. The remaining parts of business taxes can be improved later. In fact, tackling a difficult portion of tax reform could help efforts for a broader overhaul because that hard work would already be done. Thus, it would be useful if Congress could move to the territorial system of taxation, which would increase America’s competitiveness. However, Congress should be careful not to accept scaled-back approaches to business tax reform, such as the creation of innovation boxes, which would hurt the chances of fundamental tax reform in the future.

Congress should not use this opportunity to increase spending by taxing income earned abroad. Congress needs to cut spending—not increase it.

Time for a Course Correction

The need for external budgetary enforcement to correct the U.S. fiscal course is clear. Congressional Budget Office and Office of Management and Budget data indicate that U.S. publicly held debt as a percentage of GDP will grow to 183 percent by 2039 and that federal health care programs, Social Security, and interest on the debt will consume all projected tax revenues (assuming current policy) by 2031.[81] Debt levels this high will weaken economic growth, and significant federal interest payments will crowd out other spending on the necessary functions of government.

When approaching the fiscal challenges this fall, Congress therefore should:

- Cap and cut spending and put the budget on a path to balance before increasing the debt limit.

- Put the major entitlements on a budget, adopt an expenditure limit on all non-interest spending, and pursue a spending-focused, constitutional balanced budget requirement to strengthen budgetary enforcement in addition to the debt limit.

- Adopt a full-year continuing resolution before the end of this fiscal year at the levels established in the BCA, with the necessary policy changes, and fully fund national defense.

- Devolve surface transportation funding to local governments and the private sector.

- Move the tax code closer to an ideal system while making fundamental reform easier to achieve.

Congress has the opportunity from September to December 2015 to cap and cut federal spending, move to budget balance, and reform aspects of taxation to encourage the economy to grow. Such steps to cap and cut, balance, and grow will strengthen America’s ability to provide opportunity for all.

—Paul Winfree is Director of the Thomas A. Roe Institute for Economic Policy Studies, of the Institute for Economic Freedom and Opportunity, at The Heritage Foundation. Romina Boccia is Grover M. Hermann Research Fellow in Federal Budgetary Affairs and Research Manager in the Roe Institute. Curtis S. Dubay is Research Fellow in Tax and Economic Policy in the Roe Institute. Michael Sargent is a Research Associate in the Roe Institute.

APPENDIX

Securing the Future: The Need for a Balanced Budget Amendment

The weakness of a statutory law imposing an aggregate cap on spending is that a future Congress can amend the law. Deficit spending almost always favors the current generation over future generations that will pay for the spending of today. Therefore, a balanced budget amendment is needed to constrain future attempts to eliminate the spending cap.[82]

The balanced budget amendment is not a mechanism to achieve balance and should not be viewed by Congress as a substitute for making necessary reforms to federal programs. Rather, the balanced budget amendment should be used to guarantee the hard work of reforming programs cannot be easily undone in the future.

Political analysts from James Buchanan to David M. Primo have argued that in the long run, Congress should establish a constitutional budget constraint to rein in the political tendency to engage in deficit spending. James Buchanan argued in 1995:

The proposed balanced budget amendment lays out a new rule for making fiscal choices; it does not lay down guidelines for what these choices might be. In one sense, the proposal may be too simple to be understood. In its bare-bones formulation, the amendment requires only that congressional majorities, within the other constraints through which they are authorized to act, pay for what they spend, with “pay for” being defined in a willingness to levy taxes on those citizens who make up the current membership of the polity.[83]

David M. Primo laid out 10 principles for budget rules in 2014, concluding that “While there are pros and cons to Constitutional rules, without this external enforcement, budget rules will always be vulnerable to legislators’ propensity to break them.”[84] Recent International Monetary Fund research covering 33 expenditure rules between 1985 and 2013 further suggests that spending limits perform better over time than do balanced budget requirements or debt limits:

Our findings suggest that expenditure rules are associated with spending control, counter-cyclical fiscal policy, and improved fiscal discipline. We find that fiscal performance is better in countries where an expenditure rule exists. This appears to be related to the properties of expenditure rules as compliance rates are generally higher than with other types of rules (on the budget balance or debt, for example). In particular, we find that compliance with expenditure rules is higher if the expenditure target is directly under the control of the government and if the rule is not a mere political commitment, but enshrined in law or in a coalition agreement.[85]

A balanced budget amendment to the U.S. Constitution is important because it can help to bring long-term fiscal responsibility to America’s future. America cannot raise taxes to continue its overspending because tax hikes take money from our people, shrink our economy, and grow our government. America cannot borrow more to continue overspending because borrowing puts an enormous financial burden on the American children of tomorrow and grows our government. America needs its government to spend less because less government spending will advance the interests of the American people in limited government, individual freedom, and free enterprise.

The balanced budget amendment must control spending, taxation, and borrowing; ensure the defense of America; and enforce the requirement to balance the budget. The constitutional amendment ratification process may take time: The fastest ratification took less than four months (the Twenty-Sixth Amendment on the 18-year-old vote), and the slowest took 202 years (the Twenty-Seventh Amendment on congressional pay raises). Thus, House and Senate passage of a balanced budget amendment must be in addition to, and not seen by Congress as an excuse to avoid, current hard work to cap and cut federal spending, balance the federal budget through congressional self-discipline, and reform and reduce taxation.