Upon awarding him the National Humanities Medal in 1999, President Bill Clinton praised John Rawls as “perhaps the greatest political philosopher of the twentieth century” who “helped a whole generation of learned Americans revive their faith in democracy.”[1] Since the publication of his first book, A Theory of Justice, in 1971, Rawls has indeed been the fashion of the academy, and his influence has increasingly spread beyond the ivory towers of American universities.

Today, Rawls’s theory—which defends the principles of egalitarianism, toleration, consensus politics, and societal fairness—informs much of contemporary liberalism’s aspirations, constitutional interpretations, domestic policies, and public rhetoric. It is hardly an exaggeration to say that the principles behind such laws as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, or Obamacare, are most thoroughly argued by John Rawls. Much the same can be said of the Supreme Court’s reference to the “evolving understanding of the meaning of equality” in the 2013 same-sex marriage case, U.S. v. Windsor. Rawls’s silent influence has been immense.

Rawls believes that by rethinking America’s first principles we can make our world better. The difficulty, as he sees it, is that American society is filled with many competing notions of the good life and therefore different views of justice. This, in turn, leads to conflict. Rawls’s resolution is to define a theory of justice upon which everyone could agree without having to give up their personal convictions about the good life.

Ultimately, however, Rawls’s theory makes sense only if one accepts the claim that justice can be disassociated from any single conception of the good life. If we cannot make this intellectual leap, then Rawls disappointedly asks “whether it is worthwhile for human beings to live upon the earth.”[2] The choices he presents are stark, which partly explains why most people have strong reactions both for and against his work.

These strong reactions are mirrored in American politics today: Rawls-inspired policies (Obamacare) and Supreme Court decisions (U.S. v. Windsor) are met with passionate responses on both sides of the political aisle. His project takes American constitutionalism as a given, but it is ultimately in opposition to the political thought of the American Founders.

Life

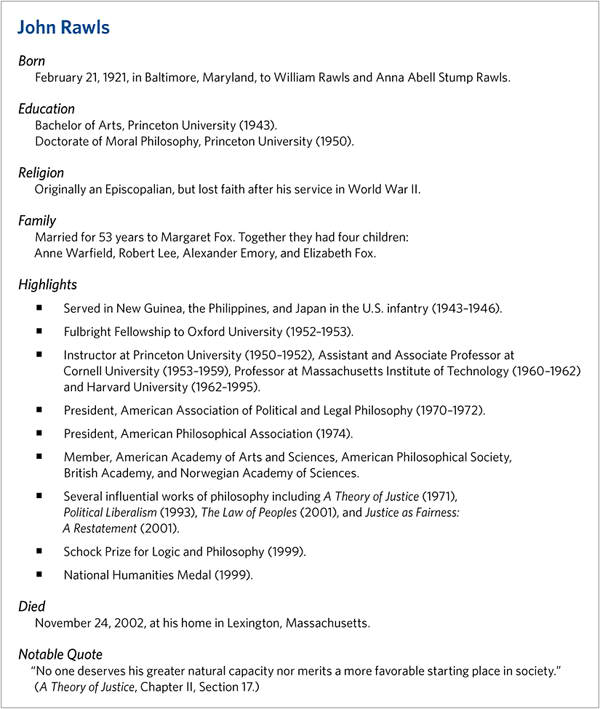

Though John Rawls spent his adult life as an atheist, it is impossible to fully understand his work without noting his relationship to religion, particularly Christianity. Born February 21, 1921, in Baltimore, Maryland, Rawls grew up in what he called a conventionally religious household.[3] The second of five boys, Rawls attended an Episcopal church in Baltimore with his mother, father, and brothers, though the family was not particularly zealous in its faith.

Whatever Rawls’s father William Rawls felt about religion, it is clear that he had a passion for the legal profession. At the age of 14, William left school to help support his family by taking a job for a local law firm as a runner. Though his duties were menial, he spent his spare time in the firm’s library teaching himself law. At the age of 22, he passed the bar exam and joined one of the oldest law firms in the country, which had been founded by William Marbury of the famous Marbury v. Madison case. William Rawls had a successful career and even argued a case before the United States Supreme Court.[4]

Despite his exposure to the law at a young age, John Rawls was not drawn to following the path of his father. He left for Princeton University in the fall of 1939 without a clear idea of what he would study. He tried various disciplines—chemistry, mathematics, art, and music—before settling on philosophy. During his last two years at Princeton, Rawls became increasingly interested in religious questions and more orthodox in his faith. He seriously considered becoming a priest in the Episcopal Church.

The extent of Rawls’s faith is evident in his undergraduate thesis, A Brief Inquiry into the Meaning of Sin and Faith, which was published posthumously (without Rawls’s prior arrangement) in 2009. The work contains many of the themes present in Rawls’s professional publications, such as a concern with morality, a critique of inequality, and a sincere hope for a better world. Though he says little of democracy or constitutionalism in the thesis, he clearly wants to make Christianity more compatible with egalitarian politics.

Rawls enlisted in the Army shortly after his graduation from Princeton in 1943. He was no stranger to tragedy—two of his brothers died at a young age—but for reasons he could not fully explain, his three years in the Pacific changed the course of his life and his beliefs. Many of his friends were killed, and he risked his own life on many occasions. He also saw Hiroshima shortly after it was destroyed by the atomic bomb. This affected him greatly, as did revelations of the Holocaust in Europe. He wondered how a benevolent God could have allowed such evil to take place. He began to question Christian doctrines and quickly lost his faith.

After the war, he returned to Princeton to pursue a doctorate in philosophy. His dissertation was an attempt to formulate a method for judging moral arguments. In that work, Rawls was reacting to the relativistic claim that morals cannot be judged because they are merely subjective values. Rawls denied this, but he also denied that any one moral claim, including any of those grounded in religion, could be used as a standard for judging other moral claims.

Herein lies the basic concern underlying all of Rawls’s work: How do we agree on a standard of justice that does not privilege any one conception of morality or the good life? He is convinced that if our social interactions are based upon a vague consensus and if we can agree to disagree about life’s most fundamental questions, then hatred, bigotry, violence, persecution, and intolerance will be eliminated.

As a graduate student, he married Margaret Fox, or “Mard,” with whom he enjoyed a 53-year marriage that produced four children. He received a PhD in 1950 and in 1952 was granted a Fulbright Fellowship to study at Oxford for the year. This was a formidable part of his education. At Oxford he studied with famous philosophers such as H.L.A. Hart, Isaiah Berlin, and Stuart Hampshire. Upon his return to the United States, Rawls held a series of jobs before finally landing at Harvard.

Rawls taught at Harvard for over 30 years, from 1962 through the mid-1990s when his health began to fail. During this time, he taught or influenced many who have since gone on to careers teaching philosophy and political theory at prestigious universities—people such as Thomas Nagel, T. M. Scanlon, and Joshua Cohen. He frequently taught survey courses on the history of moral philosophy and political philosophy, and his lecture notes from both courses have been published.[5] The final book he worked on during his lifetime, Justice as Fairness: A Restatement, was also derived from his lecture notes.[6] By all accounts, Rawls took his job as teacher seriously and through that role became increasingly familiar with the seminal works of Western political thought, including those of Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Immanuel Kant.

Rawls’s first and most famous book, A Theory of Justice, was published in 1971 and was met by an enthusiastic academy.[7] The book was an attempt to rehabilitate the social contract tradition upon new terms that Rawls hoped would better reconcile the competing claims of individuals and the community. Though the book says little if anything about contemporary political life in America, many saw it as an after-the-fact theoretical grounding for the civil rights movement. The book was tremendously successful, though it also met with criticism. Two of the most notable critics were colleagues of Rawls at Harvard, the libertarian-leaning Robert Nozick and communitarian-leaning Michael Sandel. Rawls responded to both in his latter publications.

Generally speaking, Rawls was willing to engage his critics and even make changes in his theory where he was convinced they were correct. Over the course of 20 years, he tinkered with his theory in public lectures and essays. Finally in 1993, Rawls published his second major book, Political Liberalism, which revised aspects of the earlier book. Most important, Rawls hoped to persuade Christians to accept his theory and agree to put a public conception of justice ahead of their convictions about the good life. In other words, Rawls hoped to prove that his theory was compatible with Christianity. Rawls’s influence in this regard can be seen in those Christian theories of social justice that treat social equality as religious dogma.

Rawls began to suffer from a series of strokes beginning in 1995, thus ending his teaching career. He was able to finish several writing projects with the aid of his wife and students, including his lecture notes and his theory of international relations, The Law of Peoples. Rawls passed away in November 2002.

A Theory of Justice

Although Rawls lost his religious faith, he remained deeply concerned with moral questions. In a very general sense, Rawls’s academic career can be characterized as an attempt to justify morality in the absence of religion. Rawls never claimed to be devising a method that could prove some moral claims to be true and others false. Rather, his idea was to argue for a set of standards that everyone (or most people) would accept as “reasonable.”

Reasonableness, for Rawls, becomes the new standard of judgment. Thus, anything that does not meet the Rawlsian standards is to be considered not false or wrong, but “unreasonable.” Likewise, anything that meets the standards is not true, but “reasonable.” Therefore, while there may be only one moral claim that is true, there can be several that are “reasonable.”

A political problem arises when people with different moral views, all of which may be reasonable, have to live and cooperate with one another in a democratic society. How do you ensure that no one’s moral doctrines—assuming that they are reasonable—are privileged over others?

This is the question Rawls attempts to answer in his first and most famous book, A Theory of Justice (1971). In doing so, Rawls turns to a tradition of political thought that is very much at home in America—the social contract tradition. Though variants of the idea can be traced to antiquity, the American Founders drew heavily from John Locke’s Second Treatise of Civil Government, which begins by imagining what life was like before government. In the state of nature, Locke argues, everyone is equal and free. Through the use of reason, individuals understand that they have natural rights, including the rights to life, liberty, and the acquisition of property. To protect these rights, individuals come together to form a social contract, consenting to bestow upon a government the power to preserve their lives, liberty, and property. This is the theory that informs the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution.

In the preface of A Theory of Justice, Rawls explains that he is carrying Locke’s and other social contract theories to “a higher order of abstraction.”[8] When Locke speaks of a state of nature in which there is no government, he is asking his reader to abstract from reality a bit. Locke thereby shows us that people living together without government quickly recognize the advantages of forming one to protect their rights. Similarly, Rawls also wants us to imagine a pre-political situation, but one that abstracts even further from reality: that is, a condition in which a group of people who know nothing about themselves—their ages, sexes, beliefs, or even their names—are asked to select principles of justice that can serve as the standard for a constitution, laws, and adjudications. Rawls calls this the original position. The condition of not knowing any particulars about oneself Rawls calls the veil of ignorance.

Each participant is said to represent a group of people with similar moral convictions and therefore responsible for securing principles that these people would embrace. But because they are under a veil of ignorance, they do not know what their personal convictions are and therefore have to choose principles that would be good for anyone.

The representatives in the original position do not come up with principles themselves. Rather, they choose from a list that is presented to them, presumably by Rawls, much like patrons at a restaurant ordering from a menu. The catch is that everyone ends up ordering the same thing because everyone is in exactly the same condition. No one has personal tastes of their own, and therefore, they have no preferences. They are disposed to pick that which is most generally reasonable.

Rawls invites his readers to add their own principles to the menu to see whether people under such constraints would find them desirable. Rawls is confident that his own schema, which he calls justice as fairness, will be chosen. It consists of two principles:

- Everyone should have the same basic liberties.

- Inequalities in outcomes are permissible so long as

a. Everyone has the same fair opportunities and

b. Advantages, particularly economic advantages, are to everyone’s benefit.

Rawls names 2b the difference principle, and it is one of the most controversial parts of his theory. Anticipating this, Rawls is careful to note that the first principle, that of liberty, takes priority over the second. Redistributive policies must refrain from harming people’s basic liberties.

Much of the controversy surrounding Rawls is centered on the second principle of justice. What exactly does Rawls mean by fair opportunities? He is far less clear than a careful reader would hope, but he certainly implies something more than mere legal protections for equality of opportunity. Rawls seems to encourage proactive laws that give all people the same opportunities, regardless of the advantages of birth like the wealth and influence of their parents.

Rawls does not go so far as to say that all results should be the same; he recognizes that hard work, sacrifice, and serving the community in an important capacity should be rewarded. But as the difference principle indicates, making more money is justifiable only when there is a social good attached to the extra income. It must be to everyone’s advantage to have good doctors, for example. The flip side would be a moral justification for adjusting the income of those whose salaries are out of proportion with the social goods of their services.

Rawls is careful to avoid particulars when discussing these sorts of things, apparently thinking that the implementation of the difference principle is a prudential matter left to Congress. What is important for him is that justice as fairness would be chosen in the original position by people under veils of ignorance. If Rawls can convince us of this, then Congress would presumably be justified in formulating redistributive policies.

The original position is the first stage of Rawls’s social contract theory. There are three others, and each takes a step back toward reality. This is represented by the fact that Rawls allows the imaginary parties of his thought experiment to remove parts of their veils of ignorance at each stage.

- In the first stage, they choose principles.

- In the second, they settle upon a constitution that is consistent with those principles. Rawls calls this the constitutional convention.

- In the third stage, the parties make laws in accord with their newly chosen constitution and its principles.

- The final stage is the adjudicative. Here the parties fully remove their veils of ignorance in order to judge the application of their laws in particular cases.

Whatever might be said of this four-part, highly abstract thought experiment, it clearly follows in broad outline the pattern of American government. The original position is like the Declaration of Independence in which principles are articulated. Upon this a constitution is fashioned at a convention. Laws are then made by way of that constitution, and specific cases are settled in court. It is worthy of note that Rawls repeatedly endorses judicial review as an appropriate power to be exercised by the Supreme Court to ensure that the laws and Constitution do in fact adhere to the principles of the original position.

Rawls’s theory is meant to give us a new way of thinking about the legitimacy of our Constitution, our laws, and Supreme Court decisions. He gives us a new standard for judging each and claims that this standard is one upon which all reasonable people should be able to agree. In fact, an unreasonable person is by definition someone who does not agree to the principles of the original position and is unwilling to abstract from his personal interests when advocating for laws or policies. Rawls argues that a constitutional democracy should think of its constitution and laws as something more than the rules for a game in which some people win and others lose. We could all win if we agreed to begin thinking of justice in terms of fairness rather than in terms of truth.

However much Rawls uses familiar parts of the American political tradition to build his theory, his ideas and principles differ markedly from those of the Founders.

The Founders’ Declaration of Independence proudly adhered to self-evident truths; Rawls’s original position, to the contrary, resorts to a relativistic consensus precisely because truth is not self-evident. The Framers relied upon their concrete experiences when drafting the Constitution; the parties to Rawls’s convention are guided by nothing other than abstract principles. The government created by the Framer’s Constitution is empowered to provide order yet limited by its language and structure. The government Rawls envisions is empowered to enforce a theory without any institutional restraints. The Founders maintained sober expectations when it came to the government’s role in society: Not every evil can be eradicated. Rawls is a utopian thinker who believes that the purpose of government is to rectify every injustice.

The similarities between Rawls and the Founders are superficial. It is as though Rawls takes the language of the Founders’ political thought and refashions it to fit modern liberalism’s sensibilities.

Political Liberalism

Critics of A Theory of Justice prompted Rawls to clarify and in some cases make significant changes in his previous work. Rawls was ultimately convinced that critics were right in pointing out that he had made two conflicting claims: First, he had argued that all moral convictions are personal and should be respected. Second, he held that we should all embrace the same principles of justice. The illiberal tendency of Rawls’s liberalism was not difficult to point out.

To his credit, Rawls acknowledged the conflict between the two arguments and attempted to recast the theory in more limited terms. His efforts culminated in his second major book, Political Liberalism (1993).

Though the revised version of his theory was advertised as narrower, it was also more ambitious. Rawls hoped to persuade a larger constituency to his views and welcome into the ranks of liberalism those whose private views were traditional, conservative, or religious. It was this latter group that Rawls particularly hoped to attract. In this sense, more than a strictly philosophical work, Rawls’s writings were self-consciously directed toward influencing politics.

What Rawls hoped to form was a consensus that justice as fairness was a fair standard upon which to organize government and regulate society without a definitive defense. Various groups with different moral convictions could, if they wished, argue on behalf of justice as fairness however they liked, but only if they felt the need to do so. For public purposes, it was sufficient that they simply embrace this consensus. If everyone could be convinced to do this, then adjudications, laws, and the Constitution itself could be understood in light of the two principles of justice as fairness.

This overlapping consensus was to provide judges, lawmakers, and citizens generally with a common reference point. Any public action consistent with those principles was to be understood as legitimate. In the public arena, then, all are expected to defend their ideas in terms that everyone could understand and embrace, which is to say that all are expected to use public reason.

To give publicly acceptable reasons for a policy, one simply has to pretend that they are shrouded in the veil of ignorance. If one’s argument relies on special knowledge or one’s own personal moral convictions, then it is outside the bounds of public reason, unreasonable, and illegitimate. Arguments that appeal to religion are immediately deemed suspect, because no one is privy to religion in the original position. The ideal of Rawlsian rhetoric avoids all references to God and religion or anything else above political life. One can be a religious believer in God, but only privately and not in one’s public capacity.

The revisions Rawls makes in his theory are aimed at attracting religious citizens, yet this does not mean that he has taken a step closer to the American Founders. In fact, he may be taking a step away from them. Not only were the Founders comfortable with references to God in public discourse, but they frequently made these references themselves. George Washington’s first Thanksgiving Proclamation, for example, would run afoul of Rawls’s idea of public reason.

For Washington and other Founders, religion was not simply to be tolerated but encouraged as a necessary part of the moral formation of citizens. Rawls does not think religion needs to play this role, but certainly some form of moral formation will remain. The question is: Who will fill the gap Rawls creates when he treats religion as a personal, hobby-like choice for individuals? The answer, as described below, is the Supreme Court of the United States.

Rawls and the Supreme Court

Rawls’s writing has an abstract quality that often seems disconnected from reality. Rarely does he discuss contemporary political debates in his writing. This apparent disinterest in American politics leads many to think of Rawls as a political philosopher. It may be more accurate, however, to think of him as a constitutional theorist, for his ultimate goal is to lay the foundations for a new type of constitutional democracy that is animated by consensus rather than fundamental truths.

Rawls’s constitutionalism and the United States Constitution are thus very different things. Rawls claims that his ideal constitution is built upon nothing other than a foundationless standard that can hold together a broad consensus. The United States Constitution is built upon the political theory of the Declaration of Independence, which argues that there are truths that precede human understanding and therefore consensus politics. The Declaration asks us to look to nature and nature’s God for our moral principles. Rawls tells us we cannot know about nature and nature’s God when formulating our principles of justice because this view puts nonbelievers outside of the political consensus and imposes upon them principles to which they cannot consent.

However, Rawls is not asking us to formally replace the U.S. Constitution with something new. Rather, it can be reinterpreted in accordance with those principles that arise from the original position. His new interpretation is one that he believes the Supreme Court would be justified in supplying. Its adjudications are more likely to be seen as more reasonable than Congress’s laws or executive decisions.

Rawls hoped that the implementation of his theory of justice as fairness would educate citizens in public reason. It is worth noting that Rawls became an increasingly strong defender of judicial review from A Theory of Justice onward, and though he never uses the words himself, in practice, Rawls is asking the Court to adopt a living constitution model in its jurisprudence. Justices are justified in interpreting our form of government in terms of an ill-defined political consensus that may alter from time to time, even where it is guided by the principles of the original position.

It is therefore not surprising that Rawls refers to the Court as the exemplar of public reason. If the veil of ignorance is too abstract for most to fathom, the black robe can serve as the guide in our “evolving understanding of the meaning of equality.”

The irony of Rawls’s theory, in relation to the political thought of the Founders, is that it is in many ways less democratic. While it is true that the Founders were not uncritical of democracy, they also realized it had merits that could arise more fully when its uglier tendencies were checked. They therefore had a limited faith in democracy yet allowed for it in practice insofar as the Supreme Court was not given the authority to overturn constitutional laws that struck the judges as bad policy.

One would have difficulty finding any criticism of democracy in Rawls’s thought, yet he envisions a Supreme Court with authority to guide policymakers and to ensure not only that the Constitution is followed, but also that all laws conform to moral theory. The Founders hoped Supreme Court Justices might, at best, provide a constitutional education for Americans; Rawls gives them the larger task of helping to form our moral character.

Conclusion

The divide between John Rawls and the Founders has deep roots. Ultimately, they disagree on the purpose of government and its relationship to permanent standards. This dispute is further complicated by the fact that Rawls’s theory changes the rules of civic discourse. He claims for himself the mantle of reason, while his interlocutors can be labeled unreasonable if they refuse to limit their arguments to the terms of public reason. In other words, Rawls and his followers not only want something new, but also create a new language to justify it. From the point of view of Rawls’s theory, the Founders were unreasonable, and those who think the political thought of the Founding is right and worth defending are likewise deemed unreasonable, no matter how lucid their reasons for agreeing with the Founders.

This, of course, is hardly democratic. People are granted the full status of reasonable citizens only when they give up their personal convictions in public. Rawls’s democratic dream is for generic public personas to share in governing—all transcendent perspectives are not only discouraged, but outlawed. If this is democratic, it is hardly liberal, for it works only if we agree to give up our most fundamental freedoms.

Rawls continuously has faith in the coming of a better world, but the institution in which he places his hope changes dramatically. As an undergraduate at Princeton, his hope was in religion without much consideration of his father’s association with the legal profession. By the end of his life, he had turned away from Christianity and instead placed his hope for a better America in the Supreme Court. It is unclear how this turn to the judiciary, the unelected branch of government, is consistent with President Clinton’s remark that Rawls has renewed learned Americans’ faith in democracy.

—Jerome C. Foss, PhD, is currently Assistant Professor of Politics at the Alex G. McKenna School of Business, Economics, and Government at Saint Vincent College where he also serves as a Fellow in the Center for Political and Economic Thought