On March 28, 2014, attorneys for U.S. sugar growers charged Mexican sugar growers with “dumping” sugar in the United States at unfair prices. Although the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) eliminated tariffs between the United States, Mexico, and Canada, a loophole allows domestic producers to request anti-dumping duties to protect them from international competition.

Sugar beet and sugarcane farms account for about one-fifth of 1 percent of U.S. farms, and sugar producers account for 1.3 percent of the value of total farm and livestock production. There are 2.2 million farms in the United States. Of that total, there are just 3,913 sugar beet farms and 666 sugarcane farms.[1] This relatively small sector of the economy is very politically engaged, accounting for 33 percent of crop industries’ total campaign donations, and 40 percent of crop industries’ total lobbying expenditures. The special treatment that this relatively small interest group receives from the government drives up the price of sugar, jeopardizes export growth, and weakens the U.S. economy.

In fiscal year (FY) 2013, Americans consumed 12 million tons of refined sugar, with the average price for raw sugar 6 cents per pound higher than the average world price. That means, based on 24 billion pounds of refined sugar use at a 6-cents-per-pound U.S. premium, Americans paid an unnecessary $1.4 billion extra for sugar. That is equivalent to more than $310,000 per sugar farm in the United States.[2]

American sugar producers allege that Mexican sugar producers are selling sugar to U.S. consumers at unfair prices, but the opposite is true: U.S. sugar producers are the ones selling sugar at unfair prices to American consumers.

80 Years of “Temporary” Protection

The U.S. sugar program is a relic of the Great Depression. According to a 1958 description of the program’s origins: “The government intervened on behalf of domestic sugar growers with the Jones–Costigan Act in 1934. This act enabled the government of the United States to do to American consumers what German U-Boats had threatened during the war: cut off or cut down on imports of sugar.”[3] In 1929, the legendary Will Rogers proclaimed of sugar-tariff proponent Senator Reed Smoot: “Lot’s wife (or somebody in the Bible) turned around to look back and turned into salt. If Reed ever glances back we are going to have a human sugar bowl on our hands.”[4]

The sponsors of the 1920 Sugar Act, Senator Edward Costigan (D–CO) and Representative Marvin Jones (D–TX), each represented sugar-producing regions, and Jones was eventually recognized by the sugar industry as “Sugar Man of the Year.”[5] The 1920 Jones–Costigan Sugar Act’s restrictions on sugar imports were supposed to be temporary, but except for a brief break during World War II, they have unfailingly been modified and extended. U.S. sugar producers have benefited from 80 years of temporary protection.[6]

How the Sugar Program Raises Prices

Americans pay a big surcharge for sugar because the federal government guarantees a minimum price for sugar. To maintain this minimum price, the government restricts low-priced imports by establishing a quota that limits the amount of sugar Americans can import at relatively low tariff rates. Any imports above this quota are subject to prohibitively high tariffs. Based on 2013 world sugar prices, the average above-quota tariff rate was 88 percent for raw sugar and 73 percent for refined sugar.

Since the turn of the millennium, Americans have paid an average of 79 percent more for raw sugar and 87 percent more for refined sugar compared to the average world price. Although the gap between U.S. and world sugar prices has narrowed some in recent years, U.S. consumers still pay a significant premium. In April, the price of raw sugar in the United States was 43 percent higher than the average world price. The price of refined sugar was 39 percent higher in the United States than in other countries.[7] For FY 2013, U.S. sugar beet and sugarcane producers supplied 21.8 billion pounds of refined sugar to the U.S. market at an average wholesale price of 28.84 cents per pound, or $1.3 billion more than if U.S. sugar buyers had been allowed to pay the average global price of 22.84 cents per pound.[8]

Many Americans can recall when soft drinks were sweetened with sugar instead of corn syrup. According to one report:

[F]urther distorting the marketplace for sugar, in 1934, the U.S. government went on to impose sugar import quotas. So by the time 1984 rolled around, sugar had become an exorbitantly expensive sweetener in the United States and corporations like Coca Cola and PepsiCo were tired of paying the inflated price for this product ingredient. So in a consolidated effort to manage costs, both corporations announced in November 1984 that they were going to replace high priced sugar with cost-saving high fructose corn syrup in their beverages. It was an unprecedented move that not only rocked the sugar industry, but also dramatically changed the history of food.[9]

New Demands for Protection

The North American Free Trade Agreement took effect in 1994, but restrictions on purchases of sugar from Mexico were not eliminated until 2008. In 2014, U.S. sugar producers, fearful that competition from Mexico may undermine their ability to charge above-market prices for sugar for the first time in decades, are now asking the government to impose new tariffs on Mexican sugar. According to a spokesman for the American Sugar Alliance, “Mexico is clearly dumping sugar onto our market and seizing market share from U.S. producers.”[10] Sugar producers are allowed to seek these tariffs under U.S. anti-dumping laws. A loophole in NAFTA allows industries to pursue anti-dumping duties even though NAFTA’s purpose was to establish a North American free trade zone.

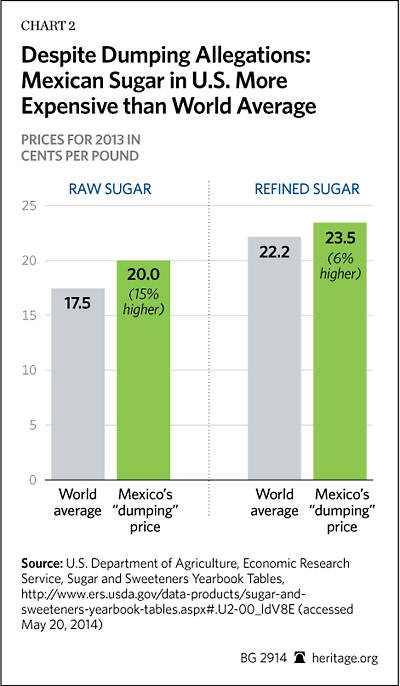

U.S. sugar producers allege that Mexican producers are exporting sugar at unfairly low prices. According to U.S. law, “unfair” means “foreign merchandise is being, or is likely to be, sold in the United States at less than its fair value.”[11] But according to the sugar growers’ anti-dumping petition, Mexican sugar is actually being sold at a price higher than the fair value of sugar, if “fair” is defined as the average world sugar price.

U.S. sugar producers claim that Mexican producers exported sugar to the United States at prices of 20 cents per pound for raw sugar and 23.5 cents per pound for refined sugar in 2013.[12] Taking those figures at face value, the price that Americans paid for raw sugar from Mexico in 2013 would have been 14.7 percent above the average world price, and the price that Americans paid for refined sugar from Mexico would have been 5.8 percent above the world price. In terms of logic, then, it is difficult to see how Mexico’s sugar producers can be guilty of dumping sugar at “unfair” below-market prices when their prices were significantly higher than the “fair” average world price of sugar.

Sugar growers are asking for tariffs of 62.34 percent on raw sugar from Mexico and 44.88 percent on refined sugar. The 146-page petition from U.S. sugar growers[13] contains no rational explanation of why Mexican sugar growers sold their sugar to Americans for significantly less than they could have earned by selling to sugar buyers in Mexico in 2013.

However, the petition does explain how the sugar growers’ lawyers manipulated the average price of sugar in Mexico in order to create an artificially inflated dumping margin. Instead of comparing average sugar prices in Mexico to average export prices, lawyers for U.S. sugar producers removed below-cost sales in Mexico before calculating the average price in Mexico. This methodology generates inflated dumping margins, or even the illusion of dumping when none exists, because it overstates the average price of sugar in Mexico. As a World Trade Organization (WTO) panel concluded: “It is, in our view, impermissible to ‘zero’ such ‘negative’ margins in establishing the existence of dumping for the product under investigation, since this has the effect of changing the results of an otherwise proper comparison.”[14]

The mere threat of new tariffs immediately had a costly impact on sugar prices. According to one report: “Prices for domestic sugar notched a 10-percent weekly gain on hefty volume as traders continued to fret that Mexican mills could curb sales into the United States, one of the world’s top sweetener consumers, in retaliation for any action the U.S. government might take following allegations that the mills were dumping sugar on the U.S. market.”[15] A U.S. sugar broker commented: “With duties, our margins would be gone. The importers are going to lose that money forever, and it could drive us out of business. We are looking at Colombian sugar, domestic sugar, Guatemalan, anything besides Mexican sugar until this thing blows over.”[16]

Interestingly, the charge that Mexican producers are dumping sugar will be investigated by the U.S. Department of Commerce and the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC), each of which has weighed in on sugar protectionism in the past.

A 2006 Commerce Department study found, “For each one sugar growing and harvesting job saved through high U.S. sugar prices, nearly three confectionery manufacturing jobs are lost.” The study concluded:

The existing literature on the economic effects of liberalization of U.S. sugar prices suggests that eliminating sugar quotas and tariff rate quotas and allowing sugar to enter the United States duty free would result in economic gains in the form of increased domestic food manufacturing production and U.S. exports, gains for consumers, taxpayer savings, and a net positive effect on U.S. employment. The United States Department of Agriculture cites the high price of domestic sugar as a main factor hindering competitiveness of the U.S. confectionery industry, and notes that sales in this industry have shown little growth over the past couple of years.[17]

According to a 2013 ITC study, “Removal of restrictions on imports of sugar would result in a welfare gain to U.S. consumers of $1,660 million over 2012–17, or an average of $277 million per year.”[18]

Protected Sugar Producers vs. Small Businesses

High U.S. sugar prices do not just mean greater costs for U.S. consumers, they also mean fewer jobs for people who work in industries that rely on sugar as an input. Jeanne Thompson of the Seattle Chocolate Company explained:

It isn’t fair for the government to be subsidizing the [sugar] farmers at the expense of manufacturers, who then either have to go out of business or certainly can’t grow to the same extent that they’d like to. I just believe in the power of free trade, and I don’t mind the fact that the chocolate industry, the premium sector, is extremely competitive, you know—bring it on! Let me be more innovative. Let me bring the best product to the market so that I can win through my efforts and innovation. I think that should be true all along the supply chain. I don’t think anyone should be given any special compensation or protection.[19]

Counterproductive Trade Policy

U.S. Trade Representative Michael Froman recently observed: “Agriculture is vital to the American economy. In 2013, U.S. farmers and ranchers exported a record $148.4 billion of food and agricultural goods to consumers around the world. In 2014, the Administration aims to help them build on that record performance.”[20] Regarding recent Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade negotiations, Nick Giordano of the National Pork Producers Council, which is calling for eliminating tariffs that protect Japan’s sensitive agricultural sectors, stated that: “The high standards of the TPP must not be sacrificed to accommodate a small, vocal group of farmers in Japan.”[21] Kent Bacus of the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association agrees: “Our expectation is that tariff elimination is part of the picture at the end of the day.”[22]

Congress just extended protection for sugar producers via the farm bill that President Barack Obama signed into law in February. Trade Representative Froman recently confessed: “Sugar is obviously a very sensitive issue in trade negotiations—always has been—and we are consulting very closely with stakeholders on the issues around sugar. But we’re not going to do anything through these trade agreements that will jeopardize or undermine the sugar program.”[23]

If the primary goal of U.S. trade agreements is to eliminate trade barriers, there should be no exceptions for a small, vocal group of farmers in Japan—nor for a small, vocal group of sugar farmers in the United States. It is difficult to convince other countries to remove their barriers to exports from competitive U.S. agricultural producers when the United States refuses to remove its protection for sugar and other products.

Costly Political Blackmail

Economist Gordon Tullock explained how sugar tariffs and similar government policies impose hidden costs on the U.S. economy: “As a successful theft will stimulate other thieves to greater industry and require greater investment in protective measures, so each successful … creation of a tariff will stimulate greater diversion of resources to attempts to organize further transfers of income.”[24] According to economist Anne O. Krueger:

The harm that protection inflicts on consumers is, nowadays, widely discussed and understood among those who argue in favor of free, and freer, trade. I don’t want to downplay this aspect. But … I … argue that the impact of protectionism on other producers, and on the macroeconomy as a whole, is far greater than has been generally recognized.… [T]hese costs are difficult to measure or estimate; and this is an important factor in their being overlooked. The ability of special interests to manipulate political decision-making processes has compounded the problems and, in my view, serves to highlight both the need for institutional change at [the] national level and the importance of a multilateral approach to free trade.[25]

In the United States, once the government bestows political favors on one industry, others come to Washington to seek their own special treatment or to fend off special-interest requests from competing industries. The influx of special-interest-seeking businesses and lobbyists drains billions of dollars from the U.S. economy, but it has paid off for the region surrounding the nation’s capital, which now includes six of the country’s 10 richest counties.[26]

In this case, U.S. sugar producers may have learned from tomato growers, who recently used the threat of anti-dumping duties to convince Mexico’s tomato growers to “voluntarily” increase the price they charge their U.S. customers. The Mexican tomato growers accepted an agreement which, according to U.S. Under Secretary of Commerce for International Trade Francisco J. Sánchez, “raises reference prices substantially, in some cases more than double the current reference price for certain products, and accounts for changes that have occurred in the tomato market since the signing of the original agreement.”[27]

Sugar represents just 2 percent of the total value of U.S. crop production, but the industry accounts for 33 percent of crop industries’ total campaign donations and 40 percent of crop industries’ total lobbying expenditures.

There is nothing wrong with sugar producers lobbying Congress and supporting political candidates, but there is a problem with costly government intervention in the economy on behalf of special interests. As Senator Mike Lee (R–UT) recently commented: “To be clear, the problem I’m describing is not that there is too much money in politics, it’s that there’s too much politics in the economy.”[28]

Time to Stop Protecting Special Interests Through Unfair Trade Rules

In contrast to trade negotiators, economists are very clear about what kind of policy the United States should pursue. According to Jagdish Bhagwati: “The fact that trade protection hurts the economy of the country that imposes it is one of the oldest but still most startling insights economics has to offer.”[29] Milton Friedman observed that: “There are so many stupid things that government is doing that, clearly, it would be in the self-interest of the public at large to have repealed. Who would—who can really on logical grounds defend sugar quotas? There’s no way of defending sugar quotas.”[30]

Options for reform by Congress include:

- Eliminating the sugar program, including trade barriers that protect sugar producers from international competition.

- Agreeing to consider opening the U.S. sugar market when asking other countries to open their markets to U.S. exports.

- Eliminating all tariffs and quotas on imports that are used by U.S. producers as inputs. This would include sugar used by U.S. bakers, confectioners, and dairy producers.

Will Rogers was right: “If a business thrives under a protective tariff, that don’t mean that it has been a good thing. It may have thrived because it made the people of America pay more for the object than they should have, so a few have got rich at the cost of the many.”[31] Congress should make the 80th year of temporary protection for the sugar industry the last.

—Bryan Riley is Jay Van Andel Senior Analyst in Trade Policy in the Center for Trade and Economics, a department of the Institute for Economic Freedom and Opportunity at The Heritage Foundation.