The Senate’s latest effort at comprehensive immigration reform was introduced by the bipartisan Gang of Eight in April 2013, and passed the Senate that June.[1] Titled the Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act (S. 744), it follows the same broad course as other reform bills that have failed over the past eight years, offering promises of increased border security and interior enforcement in exchange for a “pathway to citizenship” for illegal immigrants. This is not the last time the U.S. will see this type of immigration bill. Many in the House of Representatives have toyed with, and are still considering endorsing, this approach—and even if Congress passes no legislation this year, Americans can expect this approach to be revived in 2015 by the new Congress.

Like many other comprehensive legislative efforts to correct systems that are characterized as broken, S. 744 would greatly increase the size and expense of the federal workforce. And, like other such efforts, it makes numerous unlikely assumptions about the capability and capacity of government agencies to execute the tasks assigned by the bill. Reminiscent of the Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare, the Senate’s insistence on one comprehensive solution has resulted in a bill so large and complex that a variety of untested policies and procedures hidden in its depths have not been subject to public examination and debate. As is now evident with the health care system under Obamacare, untested and undebated policies can have significant negative effects, and the immigration system is no exception.

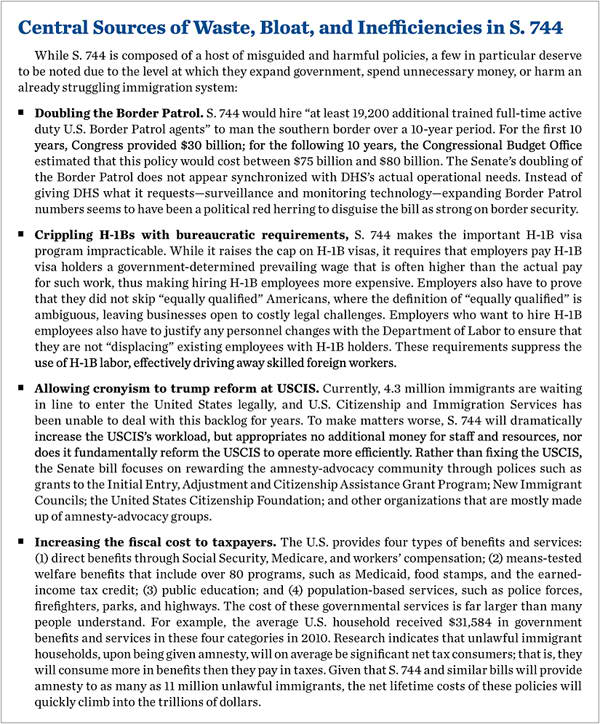

Given the clear and ongoing failure of Obamacare’s top-down, government-mandated approach, all policymakers should recognize that S. 744, or any bill that follows this big-government approach, is destined to harm the U.S. far more than it could possibly help. Several important areas of S. 744 that create unfunded, poorly designed, pork-laden, government-expanding, or overly bureaucratic programs deserve attention:

- Border security,

- Enforcement of immigration laws,

- Visa reform,

- Kickbacks for immigration advocates,

- Massive new workloads and responsibilities for bureaucrats,

- Abuse of due-process provisions, and

- The total fiscal cost of this approach to taxpayers.

Rather than continuing Washington’s reliance on massive, poorly understood, and bureaucratic pieces of legislation, the U.S. should pursue real step-by-step reforms that address the underlying problems of the U.S.’s immigration woes.[2] By starting with pieces that restore integrity and efficiency to the process, the U.S. immigration system can once again serve the U.S. economy and society.

Throwing Money at the Border

The Senate devotes $30 billion over 10 years to the hiring of “at least 19,200 additional trained full-time active duty U.S. Border Patrol agents” to work the border with Mexico, essentially doubling the number of border agents.[3] The bill places a future requirement of no fewer than 38,405 agents on the southern border by 2024, which is twice the number of agents on the southwest border now.[4] When S. 744’s funding expires, the discretionary costs for this workforce “are projected to total between $75 billion and $80 billion over the 2024–2033 period, about $55 billion more than under the committee-approved bill,” according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO).[5]

Critically, it is unlikely that this expensive doubling of the agents on the southern border is necessary or desired by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). When testifying about immigration reform on February 13, and on the bill itself on April 23, 2013, then-DHS Secretary Janet Napolitano did not request any significant increases in border patrol agents, but instead focused on the operational benefits that surveillance technologies could offer the Department.[6] It was only on June 20, when Senators Bob Corker (R–TN) and John Hoeven (R–ND) sought to add “momentum” to S. 744 by offering a 114-page amendment featuring $38 billion in border-security spending (which Senator Corker acknowledged as “almost overkill”) that this remarkable expansion of the federal workforce gained traction in the Senate.[7] Current Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson may feel the same way: While he recently pledged his support for S. 744 and applauded the doubling of the Border Patrol in the late 2000s, he said nothing about the need to do it again.[8]

Perhaps the Border Patrol could use more agents, given that it apprehends about 1,000 illegal border crossers each day of the year, and may be catching less than half of the illegal flow.[9] But the point remains that the Senate’s doubling of the Border Patrol does not appear synchronized with DHS’s actual operational needs. Instead of giving the Border Patrol what it says it needs—surveillance and monitoring technology—the ramping up of Border Patrol agent numbers seems to have been a political red herring to disguise the bill as strong on border security. In any event, having additional agents will not do much good in the face of an Administration unwilling to enforce existing immigration laws and deport those who are caught by the Border Patrol trying to cross into the U.S. illegally.

In addition to the questionable increase in Border Patrol agents, the Senate bill includes various grant programs and other new bureaucracies to deal with border issues. One such program, which may sound good on paper but does not work well in practice, would provide individuals who reside or work in the southwest border region and who are “at greater risk of border violence” due to lack of cell phone coverage with free GPS-equipped satellite phones and service plans.[10] Commercial satellite phone units can cost between $600 and $1,700 apiece, and airtime is markedly expensive (outgoing calls can average $0.85 a minute; inbound calls $10 a minute).[11] However, Congress has set no limit on the number of people who would qualify for these grants, and provided little insight on how the program would be managed. It is reasonable to assume that the program will be as subject to fraud as are subsidized phone services, which the Government Accountability Office has been complaining about for nearly a decade.[12]

The Senate bill would also create plenty of new border security bureaucracies. For one, S. 744 would create a new Southern Border Security Commission, made up of 11 appointees “noted for their knowledge and experience in the field of border security” to advise the President, Congress, and DHS on the best means of achieving effective control of the border.[13] The commission will convene public hearings and issue what appears to be a single report in its 10 years of planned existence.[14] Like many a blue ribbon commission before it, this group may find its efforts ignored in the mix of operations, constrained budgets, and political discourse.

Similarly, S. 744 would reward pro-amnesty activists with new seats at the table. S. 744 would institute a 33-member Department of Homeland Security Border Oversight Task Force that would include civil rights advocates, tribal leaders, and representatives from “faith communities” and “higher education” to “make recommendations regarding immigration and border enforcement policies…that take into consideration their impact on border and tribal communities.” The task force would “recommend ways in which the Border Communities Liaison Offices [at Customs and Border Protection] can strengthen relations and collaboration between communities in the border regions” and federal authorities, focusing on “due process, civil, and human rights of border residents, visitors and migrants.” The task force would hold hearings, take testimony under oath, demand data, and make findings and recommendations that DHS must respond to, but not necessarily implement, and issue a report to the President, Congress, and the Homeland Security Secretary before disbanding.[15] It is virtually guaranteed that this task force would be dominated by pro-amnesty, anti-enforcement activists.

Ignoring the Central Problem: Ignoring Immigration Laws

The Senate bill is ultimately a sleight of hand that presents border security as the main immigration problem and then offers over-the-top, costly, and bureaucratic solutions to that problem. However, the bill hides and largely ignores a far more serious problem—the consistent flouting and unravelling of the U.S.’s immigration laws by executive fiat. According to Chris Crane, president of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Council,

ICE officers are being ordered by political appointees to ignore the law. Violent criminal aliens are released every day from jails back into American communities. ICE officers face disciplinary action for engaging in routine law enforcement actions. We are barred from enforcing large sections of the Immigration and Nationality Act, even when public safety is at risk. Officer morale is devastated.[16]

While this is not an entirely new phenomenon, it has been taken to new extremes by President Obama, who has issued multiple policy directives to cease enforcing immigration law against certain classes of unlawful immigrants. Most notable was the June 15, 2012, memorandum from DHS, ordering immigration officials to use their “prosecutorial discretion” to refrain from undertaking legal action against DREAMers—immigrants who were brought to the U.S. before age 16. An act of pure lawlessness, this occurred after Congress refused to pass the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act.

The memorandum redefines what “discretion” means in the immigration enforcement context. Instead of meaning commonsense use of DHS’s authority to respond to exceptions and special cases, prosecutorial discretion under President Obama means that the exception has become the rule. Even worse, this action comes less than a year after President Obama told immigration activists, “The idea of doing things on my own is very tempting, I promise you, not just on immigration reform. But that’s not how our system works. That’s not how our democracy functions.”[17] President Obama was right—ignoring laws that one has sworn to execute faithfully is not how the U.S. republic functions.

In addition to making federal immigration officials stand down from enforcing the law, President Obama has consistently sought to undermine state and local efforts to enforce existing law. Indeed, the federal government took the State of Arizona to court for passing a law, S.B. 1070, with provisions that simply mirror federal immigration law but do not meet the Obama Administration’s “enforcement priorities.”[18] Despite the federal government’s protestations, the heart of the law, which allowed Arizona law enforcement officials to check the immigration status of individuals who are arrested, stopped, or detained should they have “reasonable suspicion” that they are here illegally, was upheld unanimously by the Supreme Court.[19]

Furthermore, President Obama has repeatedly tried to cut funding for the 287(g) program, which trains and deputizes state and local law enforcement officers to assist ICE agents in enforcing federal immigration law.[20] Not only do these law enforcement officers know their communities better than the ICE agents possibly can, there are one million of them scattered across the U.S., making them a knowledgeable, well-distributed, and cost-efficient force multiplier for ICE’s limited force. Instead of S. 744’s massive and costly new bureaucracies and policies, the U.S. needs more programs like 287(g), not fewer.

The President’s consistent unravelling of U.S. immigration law is the true problem in the U.S. immigration system. But the Senate bill has precious little to say about stopping this travesty. Given the way current law is ignored, there is nothing stopping this or future Administrations from sweeping away the requirements for enforcement in the Senate bill, or any of the House bills, by executive decision or mere indifference.

Making a Cumbersome Legal Visa System Worse

The Senate bill also fails to fix how the U.S. admits immigrants and non-immigrant workers. In fact the bill manages to make the problem worse in several ways, all while expanding government even further.

Rather than fixing problems in U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), the Senate bill focuses on rewarding the amnesty-advocacy community. For example, S. 744 rebrands and refocuses the Office of Citizenship within the USCIS.[21] Since 2009, the USCIS has spent $33 million on immigrant-servicing organizations to assist 66,000 lawful permanent residents in preparing for citizenship.[22] Now titled the Office of Citizenship and New Americans (OCNA), it would receive $10 million in funding and award $20 million annually in grants to state and local governments and “other entities” to create New Immigrant Councils staffed in part by “nonprofit organizations, including those with legal and advocacy experience working with immigrant communities” to assist integration efforts.[23] Those monies would also flow to a new Initial Entry, Adjustment and Citizenship Assistance Grant Program to help those seeking immigration benefits.[24] The OCNA would in turn be supported by a new public-private partnership known as the United States Citizenship Foundation (USCF), whose council of directors would principally consist of representatives from “national community-based organizations that promote and assist permanent residents with naturalization.”[25] The USCF itself may award “grants to eligible public or private nonprofit organizations” that assist new immigrants.[26]

The USCIS would also be the home of another new office created by the bill, the Bureau of Immigration and Labor Market Research. With $20 million in funding and a commissioner appointed by the President, the bureau will designate shortage occupations, calculate annual changes to the numerical limits for nonimmigrant foreign workers, examine unemployment rates, and make recommendations to Congress.[27]

S. 744 also creates a new bureaucracy called the Task Force on New Americans.[28] It will be established by the Homeland Security Secretary, and include nine Cabinet executives and several other Administration leaders, who will focus on education programming, workforce training, health care policy, “community development challenges” and other matters impacting the “lives of new immigrants and receiving communities,” ensuring “that Federal programs and policies adequately address such impacts.” Among other things, the task force will “suggest changes to Federal programs or policies to address issues of special importance to new immigrants and receiving communities,” and help develop new legislation to address those issues.[29] It is hard to believe that the task force, with its wide variety of highly specialized and disparate issues, and lack of identified staff or funding, will be a priority for DHS or anyone else. The Senate, perhaps sensing this, wants task force members to be liaisons to their organizations “to ensure the quality and timeliness of their agency’s participation in activities of the Task Force.”[30]

In addition to the additional bureaucracy and increased spending in the U.S. immigration and visa system, S. 744 stipulates new rules and regulations that actually make the current difficult system even worse. Specifically, S. 744 makes the critical H-1B visa program essentially unworkable. While it raises the cap on H-1B visas, it requires that employers pay H-1B recipients a government-determined prevailing wage, which is often above the real private-sector pay for such positions, thus making hiring H-1B employees more expensive. Additionally, employers have to prove that they did not pass over “equally qualified” Americans, where the ambiguous definition of “equally qualified” is open to interpretation, thus opening up businesses to costly legal challenges.[31] Employers wanting to use H-1Bs also have to justify any personnel changes with the Department of Labor to ensure that the company is not “displacing” existing employees with H-1Bs. Such requirements strongly discourage the use of H-1B labor, effectively driving away skilled foreign workers.

Regardless, the requirements fit S. 744’s faulty model of blindly adding additional bureaucracies, task forces, rules, regulations, and funding as the way to fix the U.S.’s flawed legal immigration and visa system.

The Presumption of Capability

It seems a common feature of large, transformative legislation that Congress presumes a level of capability on the part of federal agencies that may not be justified, especially when it comes to information technology (IT) projects. Obamacare’s problems with its Internet portal, data security, interoperability, and reporting are but a recent example of Congress’s misplaced confidence.[32]

The Senate’s immigration bill is no different. With no hint of the complexity, expense, and time required for such tasks, S. 744 summarily directs DHS to “fully integrate all data from databases and data systems that process or contain information on aliens” from components at DHS, the Justice Department, and the State Department, and to “fully implement an interoperable electronic data system to provide current and immediate access to information in the databases of Federal law enforcement agencies and the intelligence community.”[33] But DHS has struggled for years to identify available databases that are relevant to counter terrorism and to make them electronically searchable so that information might be rapidly retrieved; and, with no specific funding to support them, these statutory mandates will likely go by the wayside.[34]

Within DHS, the USCIS has its own profound IT challenges. Having spent a reported $792 million between 2008 and 2012 to wholly replace its paper-based application system with an electronic, Web-based system, it presently allows users to complete only three small transactions online.[35] While the Senate bill is silent on the matter, the USCIS would be responsible for adjudicating the applications filed by the estimated 11.7 million illegal immigrants in the U.S. seeking “registered provisional immigrant [RPI] status” that would put them on a pathway to citizenship.[36] Somewhat perversely, S. 744 prohibits DHS from requiring the electronic filing of immigration benefit forms at least until 2020, and so the operational drag will continue to haunt the USCIS for years.[ 37]

With its existing workforce and infrastructure, the USCIS simply cannot adjudicate the many millions of new applications that the Senate bill would generate. The USCIS already has an enormous caseload, processing millions of applications each year.[38] However, the USCIS experiences frequent backlogs that have added up over time, resulting in a current waiting line of 4.3 million applicants.[39] The USCIS also has grave difficulties dealing with occasional surges in immigrant applications.[40]

The USCIS has never faced anything like the workload that S. 744 would impose on it (nor did its predecessor, the old Immigration and Naturalization Service, which famously bungled an enrollment program a fraction the size).[41] When considering comprehensive immigration reform scenarios in the past, the USCIS has informally shared that its 13,250-member staff would need to double to accommodate the surge.[42] The Senate bill simply avoids this issue altogether.

Nor does it appear that the Senate has given adequate study to the extraordinarily complex tasks that numerous federal agencies would need to perform in order to complete immigration reform as envisioned in the bill. The Senate Judiciary Committee held six hearings on comprehensive immigration reform from February to April 2013.[43] None of them featured the component heads of the DHS or Department of Justice that would be massively impacted by S. 744. Instead, the hearings were populated by immigration activists, unions, businesses large and small, clerics, lawyers, and law professors. The high-level testimony offered by the Homeland Security Secretary gave no hint of the operational challenges that DHS would face if the bill were to become law.[44]

DHS would be responsible for creating and presenting new reports and plans to Congress, adding to the already crippling system of congressional oversight. Currently, DHS is required to report to at least 119 committees, subcommittees, and caucuses that assert jurisdiction over DHS. Former Homeland Security Secretaries Napolitano and Michael Chertoff reportedly both complained that the incessant hearings, briefings, and correspondence required of DHS by Congress interfered with their ability to manage the department.[45] The Senate bill will add to the pile: At minimum, and not counting recurring or annual reporting requirements, S. 744 requires that DHS and its partner agencies produce no fewer than 72 reports, assessments, plans, or studies for Congress. The expense, in work years and dollars, is unknown.

It is also worth noting that the Senate’s Verify Employment Eligibility (E-Verify) provisions do not adequately assess and determine how all its provisions for E-Verify will be accomplished. The Senate bill does not even consider how the Justice Department’s administrative law judges will be able to manage the thousands of cases arising from appeals to the E-Verify process every year.[46]

Endless “Due Process”

It is clear that the Senate bill lacks a proper appreciation for the practical operational challenges that DHS and its partner agencies would experience if S.744 became law. This is particularly true of the process that the Senate has put in place for illegal immigrants to obtain RPI status in the United States, which is the critical first step to obtaining lawful permanent residence and, eventually, citizenship.

The illegal immigrant seeking RPI status under S. 744 must prove to DHS that he has continuously resided in the United States since December 31, 2011; submit Department of the Treasury documents showing that he owes no taxes; and complete a DHS form explaining how, when, and where he illegally entered the country.[47] Since most unlawful immigrants do not file taxes, it is unclear how the IRS would collect taxes on their unreported income. Indeed, the Internal Revenue Service would likely waive or ignore enforcement for unlawful immigrants given the difficulty that most would have in providing a full record of their income.[48] As a result, this is a fairly light burden of proof, and the illegal immigrant may receive assistance from “eligible nonprofit organizations,” which will have $50 million in grant funding from DHS to help RPI applicants and others apply for legal status.[49]

If DHS denies the application because the illegal immigrant has failed to prove his eligibility for RPI status, he is given another chance to file an amended application that includes additional evidence.[50] If the applicant is again denied, he is entitled to administrative appellate review of that denial. He is given an extraordinarily generous 90 days in which to file his administrative appeal—three times longer than people in the country illegally get now to appeal an immigration judge’s final order of removal, and six times longer than a defendant gets to appeal a criminal felony conviction in federal court.[51] If he misses that deadline, a late filing is still permissible if the applicant can show his delay was “reasonably justifiable,” a standard that is nowhere defined in the bill and which is not a legal term of art.[52] After all this, the Homeland Security Secretary can still certify any appeal for review regardless of filing deadlines.[53]

The bill does not state which group of administrative adjudicators would hear RPI appeals: It is left to the Homeland Security Secretary to establish or designate the appellate authority.[54] That responsibility may end up at the Justice Department, where the bill would nearly double the number of immigration judges by adding 225 of them at an annual cost that could reach $37 million, and increase the Board of Immigration Appeals by 90 staff members.[55] What is known is that review will be de novo, and based not only on the existing record, but also on “additional newly discovered or previously unavailable evidence.”[56] If the illegal immigrant’s administrative appeal is denied, he may seek review in a U.S. District Court, which may in turn remand the case to DHS “for consideration of additional evidence” if it is considered material and there were “reasonable grounds for failure to adduce the additional evidence” in the administrative process.[57]

This immense stack of administrative and judicial procedures has several troubling issues. First, in most administrative and judicial proceedings, applicants for benefits are commonly expected to have their evidence and documents that support their claim in hand, and litigants are commonly expected to file their appeals on time or risk having their case dismissed. The bill’s laxity on the production of evidence and the meeting of filing deadlines reflects more the strong hand of the advocacy community in shaping S. 744 than it does an understanding of the need that DHS will have to administratively close cases—to say “yes” or “no”—in order to adjudicate the millions of other RPI applications that await.

Second, as it stands, an illegal immigrant will have as long as four years after the date of enactment of the bill to gather evidence to support his RPI application, a process that allows him to repeatedly inject new evidence into his case to trigger reconsideration and remand, effectively preventing the deportation of many thousands of ineligible applicants.[58] The Senate takes pains to tell DHS that it is not obliged to remove any illegal immigrant who is ineligible for RPI status.[59]

Finally, undue layers of process such as those contained in S. 744 are very expensive. The bill allows the illegal immigrant to file a flawed application that, if denied, may be resubmitted with perhaps more and better evidence; if this perfected application is not approved, an administrative “appellate” body considers the entire case anew, perhaps with more evidence. If denied there, the illegal immigrant may go to District Court where the terms for remanding the case back to the agency to consider yet more evidence are so generous that no judge will likely pause before doing so, starting the process over again. This circle can last for many months, even years, requiring the repeated attention of agency adjudicators, litigators, and judges, all at taxpayer expense.

Additionally, throughout these potentially lengthy proceedings, S. 744 provides the Attorney General with the option of appointing counsel to represent unlawful immigrants at government expense. Section 3502 explicitly states that “the Attorney General may, in the Attorney General’s sole and unreviewable discretion, appoint or provide counsel at government expense to aliens in immigration proceedings.”[60] Furthermore, the bill requires the Attorney General to provide counsel for aliens who are minors, have mental disabilities, or are “considered particularly vulnerable.” These provisions are potential limitless handouts to immigration lawyers who will fight deportations at government expense even while the government has limited resources to try and deport unlawful immigrants.

S. 744 also expands the opportunities for unlawful immigrants to receive “nonimmigrant alien” status, a temporary amnesty, and then Legal Permanent Resident (LPR) status. Under current law, an alien who has suffered “substantial” harm as the result of a crime committed against him, and who is cooperating with government authorities in the criminal justice system can gain access to temporary amnesty and possibly LPR status at the discretion of DHS. S. 744 would expand these provisions to apply to those who “would suffer extreme hardship upon removal,” an overly broad and vague provision, or those who are victims of civil and labor rights violations.[61] Any deportation proceeding is temporarily stayed when an alien has filed claims of civil or labor rights violations or can assist the government in prosecuting such violations. As a result, one can imagine an employer in Arizona dismissing illegal immigrants pursuant to state law, and the Department of Justice, a labor union, or amnesty advocates filing a labor grievance and triggering a temporary stay of deportation proceedings to anyone who is deemed helpful to the investigation. One can also imagine an unlawful immigrant responding to deportation proceedings by filing labor-related grievances, which could trigger temporary and potentially permanent amnesty as well.

Long-Term Costs that Cannot Be Ignored

In addition to the immediate and short-term bureaucracy-expanding costs, there are severe long-term costs and consequences to S. 744 and amnesties in general. Heritage Foundation research has found that providing amnesty to unlawful immigrants under a scheme similar to S. 744 will result in as much as $6.3 trillion in net future government costs. The reason for this is quite simple. The U.S. provides four types of benefits and services including:

- Direct benefits: Social Security, Medicare, and workers’ compensation;

- Means-tested welfare benefits: Over 80 programs, such as Medicaid, food stamps, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families;

- Public education; and

- Population-based services: police force, firefighters, parks, and highways.[62]

The cost of these governmental services is far larger than many people imagine. For example, in 2010, the average U.S. household received $31,584 in government benefits and services from these four categories.[63]

These government programs are highly redistributive. Some households are net tax contributors, that is, they pay more in taxes than they receive in benefits. For example, in 2010, the average household headed by college-educated individuals received $24,839 in government benefits while paying $54,089 in taxes. Conversely, some households are net tax consumers, such as the average household headed by an individual without a high school degree that received $46,582 in benefits while paying only $11,469 in taxes.[64]

The clear divide between well and poorly educated households is particularly relevant to the discussion of amnesty because unlawful immigrants are on average less educated than citizens. Specifically, half of unlawful immigrant households are headed by an individual with less than a high school degree, while another 25 percent of household heads have only a high school diploma.[65] This means that, if given amnesty, these households will on average be significant net tax consumers.

S. 744 and similar mass-amnesty plans will provide amnesty to as many as 11 million unlawful immigrants, giving them full access to over 80 means-tested welfare programs, Obamacare, Social Security, and Medicare. A reasonable prediction would be that after amnesty, newly legal immigrants would tend to receive government benefits and pay taxes at roughly the same rates as current legal immigrants with the same level of education. This would mean that the typical unlawful immigrant household would receive nearly three dollars in government benefits for every dollar in taxes paid and the average net cost per household would be around $30,000 per year. The total burden to taxpayers (total benefits received minus taxes paid) would soon rise to over $100 billion per year. As a result, the net lifetime costs of these policies would quickly spiral into the trillions of dollars.[66]

The size of government is already unsustainable, and amnesty will make the situation worse. It is unlikely that the U.S. economy can stomach such spending and debt. To finance such deficits, taxes will have to rise, dampening economic growth and harming the standard of living of U.S. residents. In short, current citizens and legal residents of the U.S. will be on the hook for the massive spike in new net costs caused by amnesty.

Real Immigration Reform Starts with the Basics

Rather than implementing costly, government-expanding, comprehensive, and amnesty-centric immigration policies, Congress and the Administration can and should implement real reforms that do not require new laws, but use and enforce existing law with only minor alterations in spending. Congress and the Administration should:

- Improve border technology. There are real solutions that do not require throwing large sums of money at the problem. Technology in the form of cameras, sensors, and drones can help the existing Border Patrol do a better job with current manpower. Blanketing the border with agents is simply not practical, but detection technologies can help border agents watch, patrol, and respond to crossings on the border. This can be achieved with targeted investments through the normal budget and appropriations process.

- Increase collaboration with local law enforcement. Another cost-effective way to improve border security and immigration enforcement is to work with local and state law enforcement through programs like 287(g).[67] U.S. immigration officials often ignore or even work against state and local governments because the Obama Administration has decided that it wants to enforce the law only in certain ways against certain individuals. This is anything but constructive. The federal government should take advantage of the approximately one million local and state law enforcement officers, many of whom stand ready to assist in border security and immigration enforcement.

- Enforce existing law. Perhaps the simplest solution to the U.S.’s current immigration woes is to simply enforce existing law fully and faithfully. Over the past several decades, the executive branch has consistently chosen to bend or break immigration rules, and this lawlessness has reached unprecedented levels under President Obama. Immigration officials are prohibited from enforcing major parts of immigration law, to the detriment of public safety, the rule of law, taxpayers, and local, state, and federal budgets. This might require some additional funding for ICE and other immigration agencies, but the costs would be minimal in comparison to the costs of a big-government approach like S. 744 or the costs currently imposed on U.S. society by unlawful immigrants.

- Reform the USCIS. U.S. immigration agencies struggle to keep up with their current responsibilities, yet S. 744 would add huge new responsibilities without fundamental reform. This is especially true of the USCIS. The USCIS struggles due to a budget model that is based on application fees. To provide the USCIS with the flexibility it needs to reform its visa processing system, the USCIS should be given some funding via annual appropriation. This will also allow Congress to exercise greater oversight of the USCIS’s activities, such as its overdue and expensive update to the way it delivers its services and its IT requirements.[68]

Obamacare-Style Immigration Bill: Harmful to U.S.

It is often said that the U.S. immigration system is broken and requires massive changes to fix it. While the system is broken, the proposed changes under S. 744 and similar proposals in the House of Representatives only add to the confusion and do not address the root problem—the dereliction of duty by successive presidential Administrations to enforce existing immigration laws. This lawlessness has reached unprecedented levels under President Obama, and serious efforts are required to restore America’s faith in the executive.

Adding an Obamacare-style immigration bill will only confound the issue, expanding government, increasing costs, breaking the rule of law, adding special interest loopholes and handouts, and further harming security and enforcement efforts, all while ignoring the laws that currently go unenforced, and placing the costs firmly on the shoulders of American taxpayers and prospective immigrants trying to come to the U.S. legally. The U.S. should resist these harmful, bloated policies and realize that simple solutions, such as enforcing existing law and using existing authority responsibly, are a must for fixing the broken U.S. immigration system.

—David Inserra is a Research Associate for Homeland Security and Cybersecurity in the Douglas and Sarah Allison Center for Foreign and National Security Policy, a division of the Kathryn and Shelby Cullom Davis Institute for International Studies, at The Heritage Foundation.