The Senate is currently considering a massive immigration reform bill, the "Secure Borders, Economic Opportunity and immigration Reform Act of 2007" (S. 1348). This bill would grant amnesty to nearly all illegal immigrants currently in the United States.

The fiscal consequences of this amnesty will vary depending on the time period analyzed. It is expected that many illegal immigrants who are currently working "off the books" and paying no direct taxes will begin to work "on the books" after receiving amnesty, and therefore tax payments will rise immediately. By contrast, under S. 1348, benefits to these immigrants from Social Security, Medicare, and most means-tested welfare programs (such as Food Stamps, public housing, and Temporary Assistance to Needy Families) will be delayed for many years. In consequence, then, the increase in taxes and fines paid by amnesty recipients may initially exceed slightly the increase in government benefits received. In the long run, however, the opposite will be true. In particular, the cost of retirement benefits for amnesty recipients is likely to be very large. Overall, the net cost to taxpayers of retirement benefits for amnesty recipients is likely to be at least $2.6 trillion.

Who Are the Illegal Immigrants?

According to the most widely accepted estimates, there were 11.5 million to 12 million illegal immigrants in the United States in the spring of 2006.[1] Because the number of illegal immigrants has, on average, increased by roughly 500,000 each year, the number of illegal immigrants in the U.S. in 2007 is probably around 12 million to 12.5 million; however, these estimates are uncertain, and the actual number of illegal immigrants may be higher.

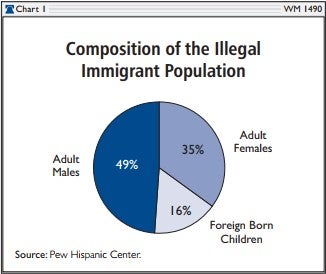

As Chart 1 shows, some 49 percent of illegal immigrants are adult males, 35 percent are adult females, and 16 percent are foreign-born children. Living in illegal immigrant families are another 3.1 million U.S.-born children of illegal immigrant parents.[2] Because they were born inside the U.S., these children are considered citizens, not illegal immigrants.

Illegal immigrants now make up about 4 percent of the U.S. population, meaning that about one in twenty-five persons currently in the U.S. is here unlawfully. Illegal immigrants make up nearly one-third of the foreign-born population in the U.S.

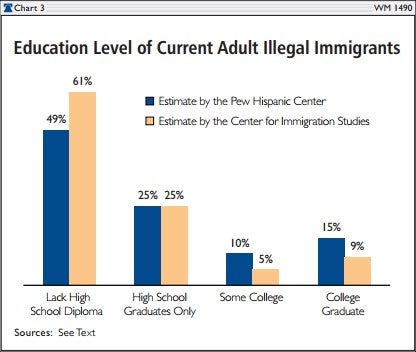

As Chart 2 shows, more than half (56 percent) of illegal immigrants come from Mexico. Another 22 percent come from other Latin American countries, and 22 percent come from Asia, Europe, and Africa.[3]

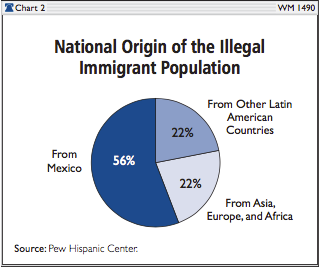

Education of Illegal Immigrants. Illegal immigrants generally have very low education levels. As Chart 3 shows, 61 percent of illegal immigrant adults lack a high school diploma, 25 percent have only a high school diploma, 5 percent have attended some college, and 9 percent are college graduates, according to the Center for immigration Studies' estimates.[4] The Pew Hispanic Center estimates slightly higher education levels: 49 percent without a high school diploma, 25 percent with a high school diploma only, 10 percent with some college, and 15 percent with college degrees.[5] Overall, 49 to 61 percent of adult illegal immigrants lack a high school diploma, compared to 9 percent of native-born adults.

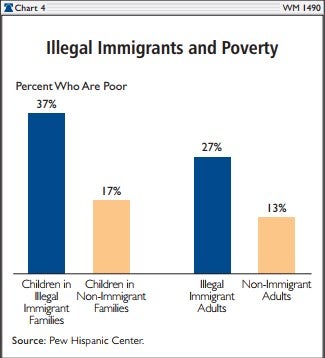

Illegal Immigrants and poverty. Because of their low education levels, illegal immigrants have a poverty rate that is roughly twice that of native-born Americans. As Chart 4 shows, the poverty rate of children in illegal immigrant families is 37 percent, compared to 17 percent among children in non-immigrant families. The poverty rate among adult illegal immigrants is 27 percent, compared to 13 percent among non-immigrant adults.

S. 1348 and the amnesty Process

The Senate's immigration reform bill would offer amnesty and a path to citizenship to the 12 million to 12.5 million illegal immigrants currently in the U.S. In addition, its lax evidentiary standards would encourage millions more to apply for amnesty fraudulently. Because there is no numeric limit on the number of amnesties that could be granted under the bill, the actual number who would receive amnesty under the bill could be far higher.

In general, under S. 1348, any person who was illegally present inside U.S. borders on January 1, 2007, is eligible for Z visa status, amnesty, and ultimately citizenship. Excluded from this rule are illegal immigrants subject to a formal deportation order issued prior to enactment of the legislation and illegal immigrants convicted of a felony or three misdemeanors prior to enactment. The amnesty process consists of four stages leading to citizenship.

Stage One: Probationary Z Visas. Within 180 days of enactment of the bill, the Secretary of Homeland Security would begin accepting applications for Z visa status from illegal immigrants. The Secretary can accept applications for up to two years. The Secretary must grant "probationary Z visa" status to all amnesty applicants who pass a background check that must be completed within one business day. Except for those failing the one-day background check, applicants will automatically be granted probationary status and issued appropriate documents on the day after their application, even if the background check has not been completed.[6]

Stage Two: Permanent Z Visas. The Secretary must issue a permanent Z visa to every applicant who is determined to have met four conditions: the individual was inside the U.S. unlawfully on January 1, 2007; has not left the U.S. for more than six months since then; is employed or is the spouse or child of an employed applicant; and has passed more thorough criminal background checks that may be required. Each Z visa is good for four years and can be renewed indefinitely for the rest of the Z visa holder's life.[7] The Secretary cannot grant permanent Z visas unless the modest enforcement trigger provisions of S. 1348 have been met.[8]

Stage Three: legal Permanent Residence (LPR).All Z visa holders who pay a $4,000 fine and pass an English test would become eligible for legal permanent residence (also known as green card status). Z visa holders must go abroad to apply for LPR status but may return to the U.S. the same day. No later than 8 years after enactment, the Secretary of Homeland Security must determine the number of Z visa holders who are eligible for legal permanent residence and grant LPR status to all such persons over the following five years at a rate of 20 percent per year.[9]

During this process, Z visa holders would be granted their own special "supplemental allocation" of green cards and would not be required to compete with other visa seekers.[10] In the 13th year after enactment, the Secretary must provide an additional allotment of green cards to Z visa holders who are qualified for Z visa status.

Stage Four: Expanded Eligibility for Government Benefits. During the initial years an immigrant is in LPR status, access to government welfare programs may be limited; however, after five years in LPR status, individuals become eligible for nearly all welfare programs. legal permanent residents may also apply for U.S. citizenship at this point.

Eligibility for Government Benefits

The following outlines eligibility for government benefits at each stage of the amnesty process. In each case in the following text, eligibility for a benefit means that the former illegal immigrant or his family member obtains the same eligibility for that program as a U.S. citizen would have; that is, he will receive the benefits if income limits and other normal eligibility standards applying to U.S. citizens are met.

Probationary and Permanent Z Visa Status. All children born within U.S. borders to illegal immigrants, Z visa holders, or legal permanent residents are automatically U.S. citizens. As such, these children are potentially eligible for all U.S. welfare benefits from the moment of birth through the rest of their lives. All children of Z visa holders (both foreign- and native-born) have the right to attend U.S. public schools and to receive Head Start and daycare assistance.[11] In addition, adult Z visa holders and their foreign-born children will be eligible for medical care under the Medicaid Disproportionate Share Program.

All individuals placed in probationary Z visa status will be given lawful Social Security numbers,[12] which makes the Z visa holder immediately eligible for two refundable tax credits: the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the Additional Child Tax Credit (ACTC). These credits provide cash welfare assistance to low-income parents. Upon receipt of a lawful Social Security number, Z visa holders will also be granted the right to earn entitlement to future Social Security and Medicare benefits. After 10 years of employment, they will become fully eligible for Social Security and Medicare benefits, although in most cases the benefits will not commence until the individual reaches age 67.

legal Permanent Residence. Upon obtaining LPR status, the non-citizen children of former Z visa holders will become eligible for Food Stamp benefits.[13] All legal permanent residents who have a 10-year work history in the U.S. are automatically eligible for Food Stamps, Medicaid, Supplemental Security Income, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), and other welfare programs.[14] Many legal residents without a work history are eligible for Medicaid in 22 states, including California and New York.[15] Irrespective of employment history, amnesty recipients will become eligible for 60 different federal welfare programs five years after receiving legal permanent residence.

Citizenship. After obtaining citizenship, individuals become eligible for Supplemental Security Income, a means-tested cash aid program for disabled and elderly persons.

To summarize this process, all Z visa holders will be eligible for medical care benefits under the Medicaid Disproportionate Share Program. Foreign-born children of Z visa holders will be eligible to attend public schools and receive Head Start and daycare assistance. Children born inside the U.S. to illegal immigrant parents and Z visa holders will be eligible for public schooling and all means-tested welfare programs. Many state and local governments may also provide benefits and services to Z visa holders.

Upon obtaining a probationary Z visa, amnesty applicants will receive a lawful Social Security number, which makes Z visa holders potentially eligible for the EITC and the ACTC. In addition, they will begin to earn entitlement to Social Security and Medicare benefits. Roughly eight years after enactment, amnesty recipients will begin to enter LPR status and non-citizen children will become eligible for Food Stamps. legal permanent residents with a 10-year work history in the U.S. will be eligible for most federal welfare programs subject to income limits and other admission criteria. No later than five years after receiving LPR status, amnesty recipients will be eligible for nearly all means-tested welfare programs.

The initial limitation on receipt of means-tested welfare will have only a small effect on governmental costs. welfare is only part of the benefits received by immigrant families. Moreover, the average adult amnesty recipient can be expected to live more than 50 years after receiving his Z visa. While recipients' eligibility for means-tested welfare will be constrained for the first 10 to 15 years, they will be fully eligible for welfare during the last 30 to 40 years of their lives. Use of welfare during these years is likely to be heavy.[16]

In addition, if S. 1348 is enacted, many state and local governments are likely to begin giving benefits and services to Z visa holders that are greater than those currently provided to illegal immigrants. State governors of both parties will pressure Congress to relax the eligibility restrictions barring Z visa holders from receiving most federal means-tested benefits as a way of relieving fiscal pressure on state and local governments. In the present political climate, these efforts are likely to prove successful.

The Net Retirement Costs of amnesty

Giving amnesty to illegal immigrants will greatly increase long-term costs to the taxpayer. Granting amnesty to illegal immigrants would, over time, increase their use of means-tested welfare, Social Security, and Medicare. Fiscal costs would rise in the intermediate term and increase dramatically when amnesty recipients reach retirement. Although it is difficult to provide a precise estimate, it seems likely that if 10 million adult illegal immigrants currently in the U.S. were granted amnesty, the net retirement cost to government (benefits minus taxes) could be over $2.6 trillion.

The calculation of this figure is as follows. As noted above, in 2007 there were, by the most commonly used estimates, roughly 10 million adult illegal immigrants in the U.S. Most illegal immigrants are low-skilled. On average, each elderly low-skill immigrant imposes a net cost (benefits minus taxes) on the taxpayers of about $17,000 per year. The major elements of this cost are Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid benefits. (The figure includes federal state and local government costs.) If the government gave amnesty to 10 million adult illegal immigrants, most of them would eventually become eligible for Social Security and Medicare benefits or Supplemental Security Income and Medicaid benefits.

However, not all of the 10 million adults given amnesty would survive until retirement at age 67. Normal mortality rates would reduce the population by roughly 15 percent before age 67. That would mean 8.5 million individuals would reach age 67 and enter retirement.

Of those reaching 67, their average remaining life expectancy would be around 18 years.[17] The net cost to taxpayers of these elderly individuals would be around $17,000 per year.[18] Over 18 years, the cost would equal $306,000 per elderly amnesty recipient. A cost of $306,000 per amnesty recipient multiplied by 8.5 million amnesty recipients results in a total net cost of $2.6 trillion.

These costs would not occur immediately. The average adult illegal immigrant is now in his early thirties; thus, it will be 25 to 30 years before the bulk of amnesty recipients reaches retirement. At their peak level, it appears the amnesty recipients will expand the number of beneficiaries under Social Security by 5 to 10 percent. This will occur at a point when Social Security will already be running deficits of over $200 billion annually.

This is a rough estimate. More research should be performed, but policymakers should examine these potential costs very carefully before rushing to grant amnesty, "Z visas," or "earned citizenship" to the current illegal immigrant population.

Factors That Could Increase Future Costs

The $2.6 trillion figure is a rough estimate of future costs that would result from putting 10 million adult illegal immigrants on a guaranteed pathway to citizenship. There are a number of factors that could raise or lower these future costs. Among the factors that could increase the net cost (benefits received minus taxes paid) well above $2.6 trillion are the following:

- The actual number of illegal immigrants may be greater than 12 million. The estimated cost of $2.6 trillion in future retirement costs outlined above assumes that the number of illegal immigrants in the U.S. in 2007 was around 12 million, based on data from the Pew Hispanic Center. While the Pew Hispanic Center is the most widely used source for demographic information about illegal immigrants, its data assume that some 90 percent of illegal immigrants appear in the Census Bureau's Current Population Survey (CPS).[19] It is possible that many illegal immigrants do not appear in the CPS and that the total number of illegal immigrants is substantially higher than 12 million. Some estimates place the number of illegal immigrants as high as 20 million. Clearly, if the illegal immigrant population is greater than 12 million, then the net retirement costs resulting from amnesty would be, ceteris paribus, higher as well.

- There is a huge potential for amnesty fraud. In order to receive amnesty and a Z visa and be put on a pathway to citizenship, an illegal immigrant must demonstrate that he or she was in the U.S. illegally and employed on January 1, 2007. However, the standard to demonstrate residence is very loose. The illegal immigrant need merely produce two affidavits from non-relatives asserting that he or she was working in the U.S. on the appropriate date. The affidavits could even come from other illegal immigrants. It is doubtful that the Department of Homeland Security has any real capacity to separate true affidavits from bogus ones, especially in the crush of processing millions of applications in the space of a year or two. Consequently, the potential for amnesty based on fraudulent documents is very high. In the 1986 amnesty, an estimated 25 percent of the amnesties granted were fraudulent.[20] In the last 20 years, the underground industry producing fraudulent documents has grown vastly larger and more sophisticated. In this round of amnesty, the fraud rate could be as high as or higher than in 1986, resulting in millions of additional amnesties.

- Spouses and children living abroad may be added to the amnesty population. In its present form, the bill grants amnesty to employed illegal immigrants who were in the U.S. on January 1, 2007. Any spouses, children, and parents of employed illegal immigrants who were residing in the U.S. on that date will also receive Z visas and amnesty. However, many illegal immigrants have spouses and children living abroad; under S. 1348, while illegal immigrants and their families inside the U.S. are put on a path to citizenship, families living abroad are not. family members living abroad would be denied Z visas and would not be permitted to reside in the U.S. for the foreseeable future. Presumably, the Z visa holder could have his family join him when he achieves legal permanent residence, but this would not occur until eight years after he is initially given the Z visa.

The designers of the bill appear to have excluded spouses and children living abroad from eligibility for Z visas in order to lower the apparent number of amnesty recipients, but pressure will build to eliminate this exclusion. At some point, either before or after the bill's passage, a "technical correction" will almost certainly be introduced allowing spouses and children living abroad to obtain Z visas and get on the pathway to citizenship. For every 10 illegal immigrants living in the U.S., there may be four dependents living abroad; if the current illegal population is 12 million, the number of additional dependents who could be brought permanently into the country should the exclusion be eliminated may be as high as five million.[21] The overall number of amnesty recipients and dependents could easily reach 17 million.

- Medicaid and Medicare costs are likely to rise faster than the rate of general inflation. To project the future governmental costs of amnesty recipients during retirement, this paper has used the current net governmental costs for elderly immigrants with skill levels similar to the amnesty population. These net governmental costs amount to $17,000 per person per year in 2004; half of this cost was medical care expenditures under the Medicare and Medicaid programs. The cost of government Medicaid and Medicare benefits has tended to escalate rapidly both because medical cost inflation has been greater than the general rate of inflation in the economy and because the range of medical services provided by these programs has expanded. The cost of Medicare and Medicaid services is likely to continue to increase more rapidly than inflation for the foreseeable future. As a consequence, the actual retirement costs for amnesty recipients will almost certainly be greater than $2.6 trillion, even after adjusting for general inflation.

Factors That Could Reduce Future Costs

By contrast, three factors could reduce the future costs estimated in this paper:

- Not all illegal immigrants will get amnesty. The cost estimate in this paper assumes that all illegal immigrants residing in the U.S. will receive amnesty. In reality, not every illegal immigrant who was present in the U.S. on January 1, 2007, will actually receive amnesty. Some will not apply for a Z visa. Some will be found ineligible due to lack of proof of residence, despite the lax evidentiary standards. Some illegal immigrants will fail the criminal background checks and be rejected.

- Some amnesty recipients will return to their native countries. Granting amnesty and creating a pathway to citizenship creates powerful financial incentives for illegal immigrants to remain in the U.S. permanently. Nonetheless, some Z visa holders and legal permanent residents will return to their native countries before reaching old age. Even in this case, some amnesty recipients will have earned eligibility for Social Security benefits and thereby will impose governmental costs even after leaving the nation. To the extent that amnesty recipients leave the U.S. at some point in the future rather than living out their full lives in the U.S., future governmental costs will be reduced. This, however, simply underscores the fact that illegal immigrants, on average, are a fiscal burden. The longer they remain in the U.S., the greater the burden.

- The net taxes paid by second-generation immigrants may offset some costs. The average amnesty recipient will reach retirement age in 30 to 35 years. By that time, many of the children of amnesty recipients will have reached adulthood and will be receiving benefits in their own right and paying taxes. This second generation will have better education and higher incomes than their parents. In consequence, their government benefits will be lower and their tax payments will be higher than those of their parents. It is possible that, on average, these second-generation immigrants will be net fiscal contributors; the taxes they pay could exceed the benefits they receive. If this is the case, their net tax payments may offset some the government retirement costs of their parents; however, in calculating the fiscal contributions of second-generation families, it is essential to count more than Social Security taxes paid. A family that pays $3,000 in Social Security taxes while receiving $30,000 in a variety of government benefits does not contribute to governmental solvency. At present, it is uncertain to what extent, if any, the children of potential amnesty recipients will be net fiscal contributors (paying taxes exceeding total benefits). Further, even if they are net contributors, these second-generation families would have to make very large contributions in order to significantly offset the $17,000 per year net cost of their parents.

One final factor should be considered: Some illegal immigrants may become citizens, and thereby impose costs on taxpayers, even without amnesty. Under current law, a child born inside the U.S. to illegal immigrant parents is deemed a U.S. citizen. Upon reaching age 21, this child can petition for his illegal immigrant parents to be given legal permanent residence. In most cases, the petition is automatically accepted. Upon receiving LPR, the parents could begin to gain eligibility to Social Security and Medicare; within five years, the parents would become eligible for most means-tested welfare programs.

This means that, even without amnesty, some current illegal immigrants could become eligible in their retirement years for the type of benefits described in this study. Consequently, some of the costs estimated in this paper may occur without amnesty. How many illegal immigrant parents would, under current law, be placed on the pathway to citizenship by the petitions of their native-born children is unknown. Certainly the path to entitlement through the amnesty provided in S. 1348 is easier and more attractive. Nonetheless, the fact that some illegal immigrants can obtain access to government benefits under current law does not reduce the fiscal costs estimated in this paper; it simply means that a portion of these costs may occur even if S. 1348 is not enacted.

Congressional Budget Office Estimate of S. 1348

At first glance, the figures presented in this paper appear to differ from the cost estimates of S. 1348 by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO).[22] However, the CBO has estimated only the changes in benefits and revenues that would occur in the first 10 years after enactment of S. 1348. By contrast, the retirement costs analyzed in this paper will not really begin until 25 to 30 years after passage of the legislation. The current paper and the CBO study thus analyze very different impacts from the bill.

Currently, very few illegal immigrants are elderly, and virtually none receive Social Security and Medicare. A major result of S. 1348 would be to make illegal immigrants eligible for Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security during their retirement years. CBO does not address these retirement costs at all.

The CBO report does conclude that in the first 10 years after enactment of S. 1348, federal taxes and other revenues paid by Z visa holders would increase by $63 billion while federal benefits would increase by $33 billion. This should not be surprising since, as this paper has pointed out, under S. 1348, increases in tax revenues would occur immediately while increases in benefits, for the most part, would not begin for 10 years or more. However, in subsequent decades, benefits received by amnesty recipients would increase significantly. When the amnesty recipients reach retirement age, total benefits received will outstrip taxes paid by roughly seven to one. Thus, while amnesty may reduce government net costs slightly in the short run, in the long run, the fiscal effects will be substantially negative.

There are other limitations to the CBO study. First, it covers only federal benefits and revenues and ignores state and local government costs. Second, it covers only changes in spending and revenue that would result from S. 1348 and ignores the government benefits currently received by illegal immigrant families. Finally, the CBO report does not analyze the total fiscal balance of amnesty recipient families either before or after amnesty. (The total fiscal balance of a family equals total federal state and local benefits received by the family minus total taxes paid.) Similarly, it does not analyze the total fiscal balance of amnesty recipients either before or after retirement.

Policy Discussion: Reducing the Costs of immigration Reform

amnesty is not only very expensive, but it also violates the rule of law and is manifestly unfair. It gives the inestimable gift of U.S. citizenship to millions of individuals whose sole qualification for receiving citizenship is that they broke U.S. laws. Consider that on January 1, 2007, there were hundreds of thousands of foreigners in the U.S. on a variety of temporary visas. Because these individuals were here lawfully, none will be granted citizenship under S. 1348. By contrast those who were in the U.S. illegally on that same day will be given the privilege of citizenship.

Consider two foreigners who were in the U.S. on temporary visas that expired in December 2006. One of these individuals lawfully returned home upon expiration of his visa; the other chose to remain in the U.S. unlawfully. Under S. 1348, which of these individuals will be granted the privileges and benefits of citizenship? The one who broke the laws, while the individual who respected the law will have little chance for citizenship. Is this fair? Of all the people in the world who wish to come to America, why should any American feel compelled to place those who broke the laws on a guaranteed path to citizenship?

It is often argued that it is unfair to expect illegal immigrants who have spent years in the U.S. and have begun to raise families here to uproot their families and return home. But S. 1348 makes no distinction between illegal immigrants who have been in the U.S. for decades and those that have been here only a few days. Everyone who was here illegally on January 1, 2007, is potentially eligible for citizenship.

In order to constrain fiscal costs, immigration reform should include three policies:

- Emphasize enforcement. In 1986, the U.S. granted amnesty to some three million illegal immigrants as a quid pro quo for a prohibition on the future hiring of illegal immigrants. The amnesty was granted, but the prohibition on the future hiring of illegal immigrants was never enforced. S. 1348 repeats the same mistake; mass amnesty will be granted, but the border and employment enforcement provisions of the act are hollow and will probably never be enforced. To avoid repeating the mistakes of 1986, enforcement must come first.[23]

- Do not grant amnesty. amnesty is unfair and would be very expensive. Proponents of S. 1348 will argue that there is no feasible alternative to giving citizenship to all the illegal immigrants in the U.S. But serious, phased enforcement of a ban on hiring illegal immigrants would cause many, if not most, illegal immigrants to voluntarily leave the U.S. and return to their native countries. To minimize economic disruption, it might be possible to give some current illegal immigrants temporary work visas, with the explicit provision that they must return home over time. Such temporary visas would not grant access to welfare, Social Security, Medicare, or citizenship. If necessary, the exiting illegal workers could be replaced by legitimate temporary workers or by permanent immigrants who have never violated U.S. laws.[24]

- Close the "anchor baby" loophole. As explained above, under current law, when U.S.-born children of illegal immigrants turn 21, they can petition the government to grant their illegal immigrant parents legal permanent residence, thereby conferring an automatic path to welfare entitlements and citizenship upon the parents (hence the term "anchor baby"). The popular concept of "birthright citizenship"-that anyone born in the United States is automatically a U.S. citizen-is historically and legally inaccurate and ought to be corrected by Congress.[25] Regardless, this backdoor path to citizenship for illegal immigrant parents should be closed.[26]

Conclusion

There are currently at least 12 million illegal immigrants in the U.S. The immigration reform bill currently being debated in the Senate would grant amnesty to these individuals and would likely result in the entry of 4 to 5 million dependents living abroad into the U.S. as permanent residents. Illegal immigrants receiving amnesty will immediately begin earning eligibility for Social Security and Medicare benefits and, after approximately 10 years, gain access to a wide variety of means-tested welfare programs, such as Medicaid, Food Stamps, and public housing.

Because amnesty recipients have very low education levels (75 to 85 percent have only a high school diploma or less), they are likely to receive more in government benefits than they pay in taxes through most of their lives. When they reach retirement age, amnesty recipients will impose a large net cost on taxpayers, receiving each year at least $17,000 more per person in benefits than they pay in taxes. The illegal immigrants granted amnesty under S. 1348 are likely to impose a net cost of at least $2.6 trillion on U.S. taxpayers during their retirement years. Policymakers should carefully consider the potential long-term fiscal costs before enacting the amnesty provisions of this bill.

Proponents of S. 1348 will emphasize that amnesty recipients will pay Social Security taxes during their working years, thereby presumably helping to alleviate the great burden already on the government retirement system. Given their low skill levels, the Social Security tax payments of amnesty recipients will, on average, be modest. More important is the fact that, in future years, Social Security benefits will be funded by both Social Security taxes and general revenue. What matters is not the small amount of Social Security taxes that will be paid but the overall fiscal balance (total federal state and local benefits received minus all taxes paid) of amnesty recipients. If the net benefits taken by amnesty recipients and their families exceed the Social Security and other taxes paid, the amnesty recipients will undermine rather than strengthen the financial support for U.S. retirees, even before they reach retirement age themselves.

Finally, if S. 1348 is enacted, the public should expect to see a broad array of new spending proposals and programs designed to help amnesty recipients move upward economically and socially. Many of these programs are likely to be enacted into law, further increasing fiscal pressures.

Robert Rector is Senior Research Fellow in Domestic Policy Studies at The Heritage Foundation.