The reduction in the incidence of abortion during the 1990s became a topic of much discussion during the 2004 presidential election. Between 1990 and 1999, the number of reported legal abortions declined by 18.4 percent.[1] Some commentators noted that this decline took place during the Administration of President Bill Clinton, who supported abortion rights and argued that "pro-life"[2] voters receive little tangible benefit from electing Presidents who oppose abortion.[3] Others argued that these reductions were made possible partly by legislation passed by pro-life legislators and upheld by judges appointed by pro-life Presidents.[4]

Despite attention to the reduced overall abortion rate, the more dramatic decrease in the incidence of abortion among minors has received relatively little discussion. In 1985, 13.5 abortions were performed on minors for every 1,000 girls between the ages of 13 and 17. By 1999, the abortion rate for minors had fallen by over 50 percent to 6.5 per 1,000 teenage girls ages 13 to 17.[5]

Several factors may explain this decline in the incidence of abortion among minors. First, a stronger economy has been shown to reduce the incidence of abortion among adults[6] and may have had a similar impact on minors. Second, several studies have found that during the 1990s, teenagers became more likely to delay sexual activity and to abstain from sex altogether.[7] Third, pro-life legislation enacted during the 1990s, particularly parental involvement laws intended to influence minors, were effective in reducing abortion.

This analysis explores the third explanation. The regression results indicate that certain types of pro-life legislation are correlated with reductions in the incidence of abortion among minors:

- Parental involvement laws reduced the minor abortion rate by an average of 1.67 abortions per 1,000 females between the ages of 13 and 17.

- Medicaid funding restrictions reduced the minor abortion rate by an average of 2.34 abortions per 1,000 females between the ages of 13 and 17.

- The results of two natural experiments indicate that pro-life legislation, not changing values, is responsible for the declines in abortion.

Pro-Life Legislation

The 1990s witnessed a substantial increase in the amount of pro-life legislation passed at the state level. In 1992, only 20 states enforced parental involvement statutes.[8] By 2000, 32 states enforced such laws.[9] Since parental involvement laws require minors to notify or to receive permission from a parent before having an abortion, these laws could have an especially large impact on the childbearing decisions of minors.

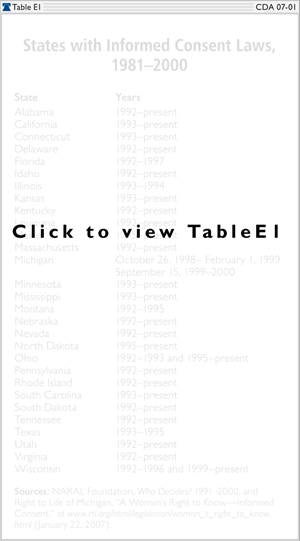

Other types of pro-life legislation gained support during the 1990s as well. In 1992, virtually no states had informed consent laws.[10] By 2000, consent laws were in effect in 27 states.[11] Similarly, in 1992, no states had banned or restricted partial birth abortion. By 2000, 12 states had passed bans or restrictions on partial birth abortion.[12]

What prompted this substantial increase in state pro-life legislation? There are two probable explanations.

First, pro-life legislation received increased legal support during the 1990s. Although parental involvement laws predated Roe v. Wade,[13] they were struck down in many cases by state and federal courts in the subsequent decades. In the 1990s, this trend halted as conservative jurists appointed by President Ronald Reagan and President George H. W. Bush gave these laws a better chance to withstand judicial scrutiny. In addition, in Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey, [14] the Supreme Court abandoned its trimester framework in favor of a doctrine of "undue burden," which gave parental involvement laws and other types of pro-life legislation broader constitutional protection.

Second, pro-life legislators made considerable and lasting gains at the state level during the 1990s. In 1994, Republicans obtained majority control of both chambers of 11 additional state legislatures. The number of states where Republicans controlled both chambers of the state legislature increased from six in 1990 to 18 in 2000.[15] As Republicans are generally more supportive of pro-life legislation than are their Democratic counterparts, their gains in state legislatures during the 1990s led to the enactment of more pro-life legislation.

Other Research

Research provides a few insights into the impact that increased pro-life legislation has had on the incidence of abortion among minors. Much of the academic literature that examines the incidence of abortion among minors focuses on parental involvement legislation. The findings suggest that parental involvement statutes reduce the number of abortions performed on minors within the borders of a given state.[16] However, researchers are divided over whether these laws reduce the overall number of abortions, in part because minors can circumvent abortion laws in their own states by obtaining abortions in neighboring states that have more permissive laws.

In analyzing the impact of Missouri's parental consent law, Charlotte Ellertson found that the minor abortion rate decreased in Missouri after passage of the law, but she also found that minors were more likely to travel to other states to obtain abortions.[17] Ellertson then posited that the increase in out-of-state abortions could be large enough to completely offset Missouri's reduction in the level of in-state abortions.[18]

In contrast, Virginia Cartoof and Lorraine Klerman found that the number of abortions performed on Massachusetts minors, both in state and out of state, fell by 15 percent after passage of Massachusetts' parental consent statute.[19] Similarly, several studies analyzing Minnesota's parental notification law have found little evidence that minors are leaving the state in significant numbers to obtain abortions in neighboring states.[20]

Although many of these studies are insightful, several shortcomings are prevalent within this academic literature.

First, many studies are limited in scope, examining only a small number of states that have enacted these policies[21] or considering data from only a relatively narrow range of years.[22]

Second, many studies focus on parental involvement laws, which are intended to influence young people. Yet the literature has largely ignored the impact of other types of pro-life legislation--public funding restrictions, informed consent statutes, and partial birth abortion bans--on abortion rates, a subject that likewise merits rigorous examination.

Third, many studies fail to correct for endogeneity problems. The enactment of pro-life legislation does not occur randomly. Unobserved influences, such as changes in prevailing social values and mores, may also be at work. Indeed, the states that are enacting pro-life laws could be the states that are becoming more religious or more conservative. Changing values and mores, not the legislation per se, may be responsible for the declines in the incidence of abortion. However, the academic literature to date does not seriously address these problems.

In the following analysis, I attempt to address these shortcomings. I collect data on abortion rates among minors in every state where data are available from 1985 to 1999. While I examine the impact of parental involvement laws, I also consider the impact of other pro-life policies, including public funding restrictions, informed consent laws, and partial birth abortion bans. Finally, I resolve the endogeneity issue by conducting two natural experiments.

Methodology

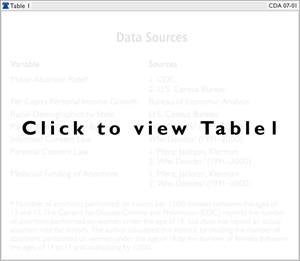

To test for the impact of pro-life legislation on the incidence of abortion among minors, multiregression analysis is performed on a dataset that includes abortion data from nearly every state between 1985 and 1999.[23] Regression analysis is well suited to this type of empirical research because it allows us to examine a number of factors that simultaneously affect state-level abortion rates.The dependent variable is the abortion rate among minors (minor abortion rate), a good indicator of pro-life legislation's impact among minors. Specifically, this variable measures the number of abortions that are performed on females under the age of 17 per 1,000 females between the ages of 13 and 17. Because this statistic is not published, I calculated it using aggregate gender and age state population data from the U.S. Census Bureau and annual state data on the number of abortions performed on 17-year-olds, 16-year-olds, 15-year-olds, and minors under the age of 15 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

To estimate the predicted effect of pro-life legislation, a number of economic and demographic factors are held constant in the analysis. To capture the economy's impact, I include each state's per capita personal income growth in the regression model. A series of variables measuring the racial composition of females between age 13 and age 17 in each state is also included in the model.

Four binary covariates indicate the individual presence or absence of four key state-level pro-life policies:

- A parental involvement requirement,

- Medicaid funding restrictions,

- An informed consent law, and

- A partial birth abortion ban.

Parental involvement rules require minors to notify or to receive consent from one or both parents before receiving an abortion.[24] Medicaid funding restrictions are state restrictions on the use of Medicaid funding for abortions deemed to be therapeutic in nature. Most states allow use of Medicaid funds for abortions when the pregnancy is the result of rape or termination is necessary to preserve the life of the mother, but state funding regulations differ in regard to abortions defined as therapeutic. Informed consent statutes, which received constitutional protection in the Supreme Court's 1992 Casey decision, require women seeking abortions to receive additional information about the abortion procedure, which may include information on fetal development, health risks involved with obtaining an abortion, or public and private sources of support for single mothers. The specifics of informed consent laws vary from state to state. Partial birth bans were upheld in 12 states between 1996 and 2000, although the Supreme Court struck down all partial birth abortion bans in Stenberg v. Carhart in 2000.[25]

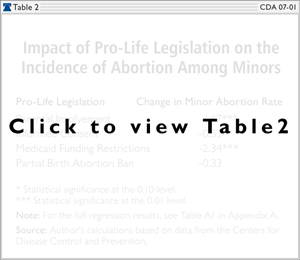

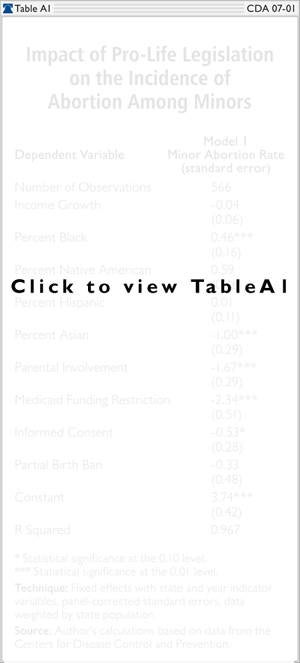

Finally, fixed effects regressions, which include separate indicator variables for each state and year present in the dataset, are utilized to hold constant geographical and time effects. The complete regression results are presented in Table A1 in Appendix A, and the estimated effects of the four state pro-life policies are presented in Table 2.

Discussion

Table 2 and Chart 1 present the regression results on the four pro-life legislation variables. Overall, the results indicate that certain types of pro-life legislation have been effective in reducing the incidence of abortion among minors. Parental involvement laws appear to have reduced the minor abortion rate by an average of 1.67 abortions per 1,000 females between the ages of 13 and 17. The coefficient estimate is statistically significant. Since the average teenage abortion rate for the years studied is about 10.18 abortions per 1,000 teenage females, parental involvement laws are predicted to reduce the minor abortion rate by an average of 16 percent.

Surprisingly, another type of pro-life legislation resulted in an even larger reduction in the minor abortion rate. Medicaid funding restrictions reduced the minor abortion rate by an average of 2.34 abortions per 1,000 females between the ages of 13 and 17. The effect of Medicaid funding restrictions also reached statistical significance. While at first glance the larger effect of public funding restrictions may seem surprising, it is reasonable to believe that public funding could affect the decisions of minors because minors in many states are eligible for publicly funded abortions if their parents are on Medicaid. In the absence of public funding, many abortion clinics may shut down or move out of state, which may reduce the abortion rate among minors.

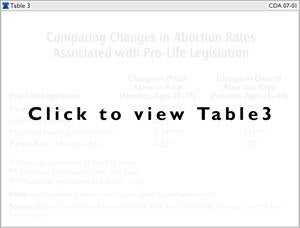

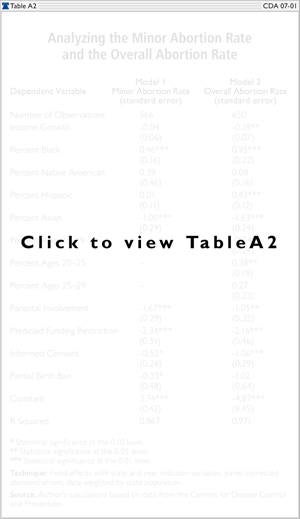

As expected, informed consent laws appear to have a negative and statistically significant effect on the overall abortion rate and the minor abortion rate, although the impact on the minor abortion rate is smaller. Both findings are consistent with expectations. If minors seek abortions because they do not want to reveal their pregnancy or sexual activity to their parents, informed consent laws that give them information about the development of their unborn children and private and public sources of support may have little impact on their decisions. Yet if adults seek abortions for reasons that are different from those of minors, such as financial hardship, informed consent laws could have a larger impact on them. This provides further evidence that legislation is influencing decisions.

Also consistent with our expectations, the results in Table 3 indicate that partial birth abortions have a larger impact on the overall abortion rate than on the minor abortion rate. This is likely because most minors, who seek abortions relatively early in their pregnancy, would be unaffected by such a law. However, we cannot be confident of this finding since neither coefficient reaches conventional levels of statistical significance. Limited data on partial abortion bans are available for analysis because most states did not enact such laws until the late 1990s. Finally, the coefficient estimates for Medicaid funding restrictions are large, negative, and statistically significant in both regressions, which is expected since children of Medicaid recipients are usually eligible for publicly funded abortions, and both minors and adults would be affected by changes in Medicaid funding for abortion.

Overall, these regression results provide solid evidence that pro-life legislation had an impact on the incidence of abortion during the 1990s. Pro-life legislation appears to be responsible for the decline in abortion among minors during the past decade. If unobserved influences such as shifts in values were responsible instead, then parental involvement laws and informed consent laws would have similar effects on the minor abortion rate and the overall abortion rate. However, the results suggest the opposite: Informed consent laws have a larger impact on the overall abortion rate, and parental involvement laws have a larger impact on the minor abortion rate. These findings strengthen the case for the effectiveness of pro-life legislation.

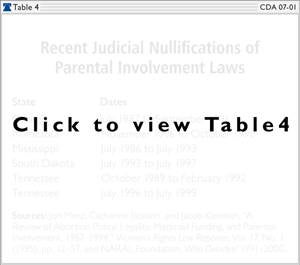

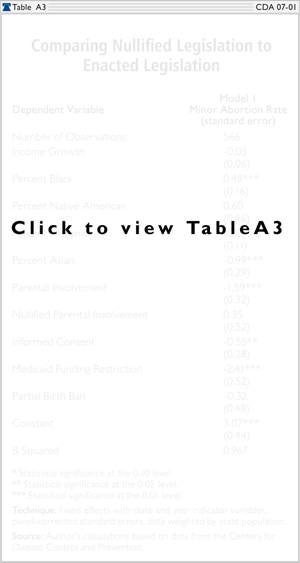

Experiment #2: Comparing Enacted Legislation to Nullified Legislation. Comparing the effects of pro-life legislation on the minor abortion rate to its effects on the overall abortion rate is one approach to fixing endogeneity problems. Another method is to compare effects on the abortion rate in states where judiciaries nullified parental involvement legislation to effects in states that retained the law.

If pro-life legislation is enacted because prevailing social values are changing, its subsequent nullification by the judiciary does not necessarily reflect a reversal in value shifts because judicial decisions are more likely to reflect the prevailing jurisprudence than they are to reflect values held by the general population. However, if the passage of pro-life legislation is attributable to shifts in values, then all states that enact such legislation could reasonably be assumed to be experiencing such value shifts, even if certain state judiciaries render adverse rulings afterwards.

Thus, if value shifts, not legislation per se, are responsible for declining abortion rates, then states where the legislation was upheld and states where the legislation was nullified would be expected to experience similar declines in the abortion rate. However, if the legislation is responsible for the declines, then states that upheld their legislation would experience, on average, significantly larger reductions in their abortion rates than would be experienced by states where judiciaries struck down the laws.

The results in Table 5 indicate that states where parental involvement laws are enforced experience, on average, a significantly larger reduction in abortion among minors than is experienced by states where the laws are nullified. Enforced parental involvement laws are correlated with statistically significant declines in abortion rates. In contrast, nullified parental involvement laws are associated with increases in the incidence of abortion, although the associated increases are not statistically significant.

Collectively, findings from both natural experiments offer solid evidence that parental involvement legislation, not value shifts that may be correlated with the passage of these laws, is responsible for the declines in the minor abortion rate.

Conclusion

Although the decline in the overall incidence of abortion during the 1990s has been widely reported, scant attention has been paid to the more dramatic reduction in abortion rates among minors. Between 1985 and 1999, the minor abortion rate fell by almost 50 percent, compared to a 29 percent decline in the overall abortion rate. While a number of factors may have contributed to this decline, the impact of pro-life legislation on the incidence of abortion among minors cannot be overlooked.

Michael J. New, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Alabama.

Some data are missing or omitted for the following reasons:

Data intentionally omitted by researcher. Data from Alaska are omitted as a result of data collection problems. Data from Kansas are omitted as well. According to CDC data, the abortion rate jumped an astounding 69 percent between 1991 and 1999, and this increase cannot be traced to any shifts in the economy, policy, or demographics in Kansas or in neighboring states. Instead, the presence of a Dr. Tiller, one of the few doctors in the country who specializes in late-term abortions, appears to be responsible for this increase. Indeed, for every year between 1992 and 1999, the CDC reports that over 40 percent of the abortions in Kansas were performed on out-of-state residents, by far the highest figure for any state.