Chief diversity officers (CDOs) charged with promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) goals have become ubiquitous on college campuses.REF Now this institutional arrangement is being exported to the K–12 education system. Many public school districts, especially large districts in Democratic states, have imitated their higher-education counterparts and created senior administrative positions and offices ostensibly to close achievement gaps and advance certain social goals.

Much like their university counterparts, the practical function of K–12 CDOs may be to provide political support and organization to one side of the debate over the contentious issues of race and opportunity. If an increasing number of school districts create positions akin to a CDO, parents and teachers who are now mobilizing against teaching critical race theory, the 1619 Project, and other radical transformations of K–12 education will be stymied.

To track how widespread CDOs are in public K–12 school districts, this Backgrounder examines 554 districts with each at least 15,000 students enrolled as of 2017.REF Those 554 districts enrolled a total of more than 22.5 million students, which was 44 percent of all students in public schools during that year. Determining whether districts employed a CDO was achieved through online searches for the name of the district as well as key terms, such as “diversity, equity, and inclusion,” and by reviewing the staff, departments, and organizational charts listed on these public districts’ websites.

In total, 39 percent of the 554 districts with more than 15,000 students employ a CDO. Among larger districts, CDO positions were much more common, with 79 percent of districts with more than 100,000 students having a CDO or its equivalent. Yet even among the 160 districts with between 15,000 and 20,000 students, 32 percent have CDOs. In blue Democratic-leaning states, 47 percent of school districts have a CDO, while in red Republican-leaning states, 32 percent of districts have CDOs.

Given the rate at which CDO positions are being created for K–12 districts, it may not be long before the vast majority of all districts have this kind of position. This Backgrounder presents information on the prevalence of CDOs in public schools, the factors associated with whether districts have such a position, and analyses of student standardized testing outcomes to see if a CDO is associated with smaller achievement gaps. The results show that the existence of CDOs may actually exacerbate achievement gaps between white and black students, white and Hispanic students, and wealthier and poor students. These findings are consistent with the observation that CDOs have more to do with political activism than with improving education outcomes—or narrowing achievement gaps between students.

The Frequency of CDOs by District Size

The size of public school districts is strongly associated with whether they have a CDO or not. The largest 28 school districts in the country with more than 100,000 students—collectively enrolling 6.2 million children—are very likely to have CDOs, with 79 percent having such a position. The only very large districts in which a CDO could not be located were the Hawaii Department of Education (which oversees the only district in the state), Duval County Public Schools in Florida, Cypress-Fairbanks Independent School District in Texas, Cobb County School District in Georgia, Shelby County Schools in Tennessee, and Northside Independent School District in Texas.

Every other district with more than 100,000 students has a CDO. The Miami–Dade County school district has an assistant superintendent for equity and diversity;REF the Charlotte–Mecklenburg County school district in North Carolina has a director of diversity and inclusion;REF the Philadelphia school district has a chief of diversity, equity and inclusion;REF the Houston school district has an executive director of equity and outreach;REF and both the Orange CountyREF and Pinellas CountyREF school districts in Florida have a minority achievement officer.

Of the 70 school districts serving between 50,000 and 100,000 students, 59 percent have a CDO. Jefferson County in Kentucky has a chief equity officer;REF Lee County in Florida has a director of diversity and inclusion;REF the Fort Worth school district has an executive director of the division of equity and excellence;REF the Alpine school district in Utah has a director of “The Equity Team”;REF Guilford County in North Carolina has an executive director of diversity, equity, and inclusion;REF the Granite school district in Utah has a director of educational equity;REF the Omaha school district in Nebraska has a director of equity and diversity;REF and the Wichita school district in Kansas has a director of equity, diversity, and accountability.REF

Among the 119 school districts enrolling between 30,000 and 50,000 students, the frequency of having a CDO dropped to 33 percent. The Portland school district in Oregon has a senior advisor for racial equity and social justice;REF the Tucson school district in Arizona has an assistant superintendent for equity, diversity, and inclusiveness;REF the Lincoln school district in Nebraska has a director of equity, diversity, and inclusion;REF the Oklahoma City school district has a chief of equity and student supports;REF and Harford County in Maryland has a supervisor of the office of equity and cultural proficiency.REF

The rate of CDO employment remains nearly the same, at 34 percent, in the 177 districts with 20,000 to 30,000 students. The Richland school district in South Carolina has a chief diversity and multicultural inclusion officer,REF the Springfield school district in Missouri has a chief equity and diversity officer,REF the Evansville Vanderburgh school district in Indiana has a CDO,REF the Olentangy school district in Ohio has an assistant director of equity and inclusion,REF and the Folsom-Cordova school district in California has a director of social emotional learning and educational equity.REF

Even among the smallest 160 school districts examined, with 15,000 to 20,000 students, 32 percent had CDOs. The Putnam City school district in Oklahoma has a district equity coordinator;REF the Oswego school district in Illinois has a director of diversity, equity and inclusion;REF the Bentonville school district in Arkansas has a CDO (who is also listed as director of security and safety; the connection between these two responsibilities is unclear);REF the Appleton school district in Wisconsin has a diversity, equity, and inclusion officer;REF and the Red Clay school district in Delaware has a director of equity and strategic partnerships.REF

The Frequency of CDOs by Partisan Dominance of State

States can be classified as blue or red states based on which party controls the state legislature and governorship. Every state except Nebraska has two legislative chambers and a governor position. Whichever party controls the majority of those three institutions is deemed to dominate the state politically. Blue states are those where at least two institutions are controlled by Democrats, and red states are those where at least two institutions are controlled by Republicans. The rate of CDO installment in school districts may be higher in blue states because the political environment is more sympathetic to the goals and activities of CDOs.

Currently there are 19 blue states (plus the District of Columbia) and 31 red states. Of the 554 school districts with more than 15,000 students, 232 are in blue states and 322 are in red states.

The likelihood of having a CDO varies dramatically based on whether a district is in a blue or a red state. In blue states, 47 percent of school districts with more than 15,000 students have a CDO. For example, in Illinois 82 percent of school districts with more than 15,000 students have a CDO. In Maryland and Minnesota, the rate is 86 percent. In Oregon and Washington, more than 70 percent of districts with more than 15,000 students have a CDO. California is exceptional among blue states in that it only has CDOs in 30 percent of its districts with more than 15,000 students. In 10 of the 20 blue states, more than half of the districts examined have a CDO.

In red states, 32 percent of school districts with more than 15,000 students have a CDO. For example, in Texas only 16 percent have a CDO. In Georgia the rate is 18 percent. In South Carolina it is 13 percent, while in Louisiana the rate is 8 percent. Among red states, Kansas is something of an outlier, because all five of its districts with more than 15,000 students have a CDO. In Indiana two-thirds of the districts have a CDO, while in Florida the rate is 42 percent. Overall, however, in only six of the 31 red states do more than half of districts examined have a CDO.

Multivariate Analysis of Whether Districts Have CDOs

It is possible that blue states differ from red states in the likelihood of having CDOs because they may have more large districts, different demographic profiles and needs, and different resources to address those needs. A multivariate regression that estimates the independent relationship of each of these factors, and the probability of a district employing a CDO, can help to separate these possible explanations.

In addition to district size and whether it is in a red or blue state, this regression considers the racial composition of the district (percentage of students classified as black, Hispanic, Asian, and a mix of two or more races); measures of student need (percentage of students qualifying for free or reduced-price lunch (FRL) and percentage of students classified as English-language learners (ELLs)); and resources spent on students (as proxied by the pupil-to-teacher ratio).

Even after controlling statistically for these other factors, the size of a school district and whether it is in a blue or red state remain strongly associated with whether school districts have CDOs. The influence of which political party controls the state actually grows larger when other factors are controlled. Blue states are 17 percentage points more likely than red states to have CDOs, after adjusting for other observable characteristics. This supports the conclusion that CDOs are designed, at least in part, to promote ideological goals.

The influence of school-district size on the likelihood that a school district has a CDO shrinks somewhat when other factors are controlled. Without making any adjustments, a third of districts with between 30,000 and 50,000 students have CDOs. The unadjusted frequency of having CDOs is 59 percent among districts with enrollments between 50,000 and 100,000. Picking the mid-points of these two groupings, an increase from 40,000 to 75,000 students is associated with a 26-percentage-point increase in the likelihood that a district has a CDO. After adjusting for other factors, however, this increase of 35,000 students is associated only with a six-percentage-point increase in expected likelihood of having a CDO.

Districts are more likely to employ a CDO when they have more black students or more students of two or more races, all else equal; but having more Hispanic or Asian students are not statistically significant predictors of whether districts have CDOs. Having more students classified as needing ELL services or qualifying for FRL were also positively related to whether school districts have a CDO. Districts with fewer resources, as measured by having more pupils per teacher, were significantly less likely to have a CDO.

The picture that emerges is that being in a larger district, in a blue state, with more black students, more ELL and FRL students, and more school resources all contribute to the likelihood of school districts employing a CDO. Being in a blue state may make CDOs more common because there is stronger political sympathy for the activities in which CDOs engage. Larger districts with more resources may be in a better position to afford CDOs. More black students, more non-English-speaking students, and more students in poverty may increase the chances of having a CDO because districts may believe that these are the groups that a CDO is meant to assist.

Do CDOs Help to Address Achievement Gaps?

The primary purpose of CDOs—according to most school district websites—is to help to reduce achievement gaps between students from different backgrounds. Differences in standardized test scores between white and black students, white and Hispanic students, and wealthier and poor students have been large and persistent for decades. By creating a CDO position, office, and staff, districts can claim that they will be able to reduce or eliminate these disparities in outcomes. If this claim were accurate, districts with CDOs should have smaller achievement gaps than districts that do not have CDOs, all else being equal.

The Educational Opportunity Project at Stanford University has student test-score data available for virtually every school district in the country.REF By merging the Stanford data with information on whether school districts have CDOs, it is possible to examine whether a district that has a CDO is in fact associated with closing achievement gaps. The analyses presented here suggest that the existence of CDOs in school districts may actually exacerbate achievement gaps. In other words, CDOs may be implementing counterproductive educational interventions.

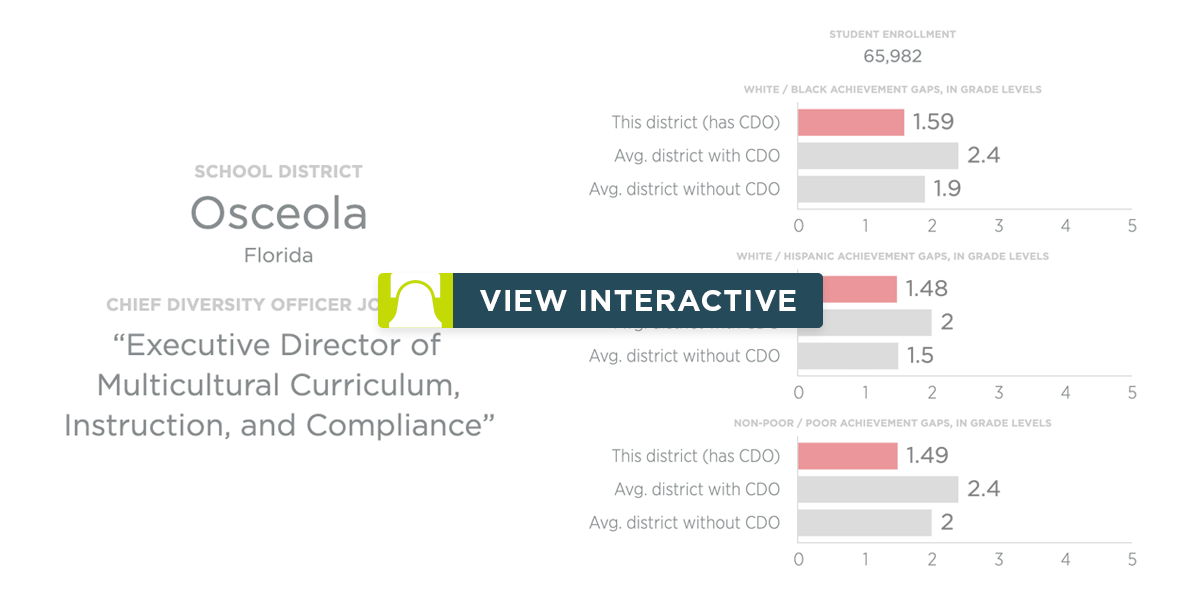

A simple comparison of achievement gaps in districts with and without CDOs shows that gaps are larger in districts that employ CDOs. In districts without a CDO, the average black student is 1.9 grade levels behind the average white student on standardized test results. In districts with CDOs, the achievement gap is half a grade level larger, with the average black student being 2.4 grade levels behind the average white student.

This pattern repeats itself for the white–Hispanic and the non-poor–poor achievement gaps. The gap between the average white and Hispanic student on standardized tests is 0.44 grade levels larger in districts with a CDO than it is in districts without that position. The gap between the average non-poor and poor students is 0.37 grade levels larger in districts with CDOs than in those without them.

Perhaps districts create CDO positions because they have larger achievement gaps that they wish to remedy. To address this concern, it is possible to examine the trend in achievement gaps, over time, rather than the static magnitude of those gaps, to see if districts with CDOs are making progress to close those gaps.

Standardized test results show that achievement gaps are growing wider over time in districts with CDOs. From 2009 to 2018, the white–black achievement gap grew by 0.03 grade levels each year in districts with CDOs relative to districts without that position. The white–Hispanic achievement gap grew by 0.02 grade levels more per year over this time period in districts with CDOs versus those without them. And the gap between poor and non-poor students grew by 0.01 grade level in districts with CDOs compared to those without them.

Even when other observed characteristics about school districts are controlled statistically, the negative relationship between a CDO position and achievement gaps remains. A regression can make statistical adjustments for differences across districts to gain a better picture of how CDOs affect achievement gaps.

Controlling for these factors provides information on whether CDOs are associated with different outcomes even when districts are of the same size, in the same political environment, have similar racial compositions, have similar student needs, have similar resources to address those needs, and have similar overall levels of student achievement and academic progress. Yet, even when districts are the same on these dimensions, a CDO remains significantly and negatively related to both the level and change in white–black achievement gaps. The white–Hispanic achievement gap and the rate of change in that gap, at least for math test scores, continues to be negatively associated with a district employing a CDO even when all of these other factors are controlled. The relationship between a CDO position and achievement gaps between non-poor and poor students ceases to be statistically significant—meaning that one can no longer be confident that the gaps differ from zero, even when other factors are controlled statistically.

Policy Recommendations

In order to increase transparency of the role of CDOs—and to prevent more CDOs from being hired who champion divisive politics in public schools—three groups can, and should, take action:

- State legislatures should oversee the process by which CDOs are hired and evaluated.

- School districts should investigate whether hiring CDOs is associated with improved academic outcomes.

- Parents should communicate with their local school boards and indicate whether they believe CDO positions should be created or expanded.

Conclusion

An analysis of student test-score data shows that having CDO positions in school districts does not contribute to closing achievement gaps and is more likely to exacerbate those gaps. If CDOs are not accomplishing their stated goals, what is accomplished by creating these positions?

CDOs may be best understood as political activists who articulate and enforce an ideological orthodoxy within school districts. They help to mobilize and strengthen the political influence of small groups of teachers, parents, or students whose preferences may be at odds with the majority of teachers, parents, and students. The creation of CDOs tilts the political playing field against efforts to remove the radical ideology of critical race theory from school curricula and practices.

For instance, parents in a central Indiana district raised concerns about a new DEI officer who was promoting a “woke ideology” that led to intolerance and bullying of those who disagreed with the program.REF In a large Virginia district, the diversity chief described one of his major goals as “making sure that equity is at the forefront of every decision that we have to make.”REF In Oklahoma, a school district hired a full-time DEI director and spent tens of thousands on equity consultants during a school year that featured declining enrollment.REF The chief equity officer in Austin, Texas, has spearheaded conversations about the existence of systemic racism.REF An equity officer in Chicago helped to implement a curriculum equity initiative that would be “fair across race, religion, ethnicity and gender”REF—which would be desirable if fairness were actually the goal.

CDOs do not and cannot promote equality in student outcomes; instead, they create inequities in political power by using taxpayer funds to aid one side in two-sided debates over controversial issues. Opponents of critical race theory and other illiberal ideas need to make the case to their local school boards that CDO positions should not be created or expanded in their districts. State legislatures could also guide districts away from creating these types of positions.

Jay P. Greene, PhD, is Senior Research Fellow in the Center for Education Policy, of the Institute for Family, Community, and Opportunity, at The Heritage Foundation. James D. Paul is Director of Research at the Educational Freedom Institute.